Role of Gastrointestinal Hormones in the Proliferation of Normal and ...

Role of Gastrointestinal Hormones in the Proliferation of Normal and ...

Role of Gastrointestinal Hormones in the Proliferation of Normal and ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

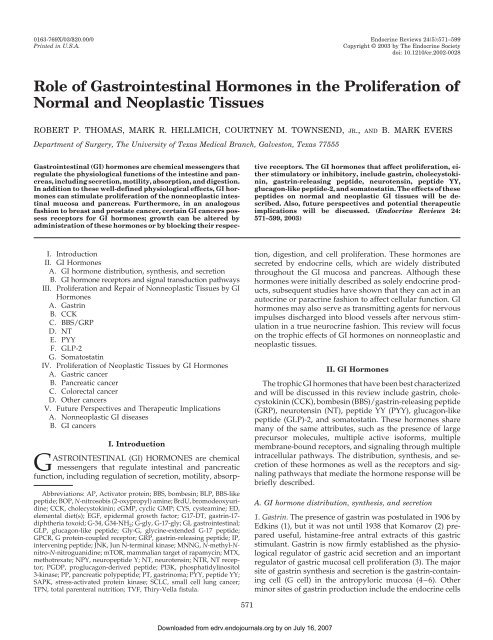

0163-769X/03/$20.00/0 Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Reviews 24(5):571–599Pr<strong>in</strong>ted <strong>in</strong> U.S.A.Copyright © 2003 by The Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Societydoi: 10.1210/er.2002-0028<strong>Role</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al</strong> <strong>Hormones</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Proliferation</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Normal</strong> <strong>and</strong> Neoplastic TissuesROBERT P. THOMAS, MARK R. HELLMICH, COURTNEY M. TOWNSEND, JR., AND B. MARK EVERSDepartment <strong>of</strong> Surgery, The University <strong>of</strong> Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas 77555<strong>Gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al</strong> (GI) hormones are chemical messengers thatregulate <strong>the</strong> physiological functions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> pancreas,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g secretion, motility, absorption, <strong>and</strong> digestion.In addition to <strong>the</strong>se well-def<strong>in</strong>ed physiological effects, GI hormonescan stimulate proliferation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nonneoplastic <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>almucosa <strong>and</strong> pancreas. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, <strong>in</strong> an analogousfashion to breast <strong>and</strong> prostate cancer, certa<strong>in</strong> GI cancers possessreceptors for GI hormones; growth can be altered byadm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se hormones or by block<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir respectivereceptors. The GI hormones that affect proliferation, ei<strong>the</strong>rstimulatory or <strong>in</strong>hibitory, <strong>in</strong>clude gastr<strong>in</strong>, cholecystok<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>,gastr<strong>in</strong>-releas<strong>in</strong>g peptide, neurotens<strong>in</strong>, peptide YY,glucagon-like peptide-2, <strong>and</strong> somatostat<strong>in</strong>. The effects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>sepeptides on normal <strong>and</strong> neoplastic GI tissues will be described.Also, future perspectives <strong>and</strong> potential <strong>the</strong>rapeuticimplications will be discussed. (Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Reviews 24:571–599, 2003)I. IntroductionII. GI <strong>Hormones</strong>A. GI hormone distribution, syn<strong>the</strong>sis, <strong>and</strong> secretionB. GI hormone receptors <strong>and</strong> signal transduction pathwaysIII. <strong>Proliferation</strong> <strong>and</strong> Repair <strong>of</strong> Nonneoplastic Tissues by GI<strong>Hormones</strong>A. Gastr<strong>in</strong>B. CCKC. BBS/GRPD. NTE. PYYF. GLP-2G. Somatostat<strong>in</strong>IV. <strong>Proliferation</strong> <strong>of</strong> Neoplastic Tissues by GI <strong>Hormones</strong>A. Gastric cancerB. Pancreatic cancerC. Colorectal cancerD. O<strong>the</strong>r cancersV. Future Perspectives <strong>and</strong> Therapeutic ImplicationsA. Nonneoplastic GI diseasesB. GI cancersAbbreviations: AP, Activator prote<strong>in</strong>; BBS, bombes<strong>in</strong>; BLP, BBS-likepeptide; BOP, N-nitrosobis (2-oxypropyl) am<strong>in</strong>e; BrdU, bromodeoxyurid<strong>in</strong>e;CCK, cholecystok<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>; cGMP, cyclic GMP; CYS, cysteam<strong>in</strong>e; ED,elemental diet(s); EGF, epidermal growth factor; G17-DT, gastr<strong>in</strong>-17-diph<strong>the</strong>ria toxoid; G-34, G34-NH 2 ; G-gly, G-17-gly; GI, gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al;GLP, glucagon-like peptide; Gly-G, glyc<strong>in</strong>e-extended G-17 peptide;GPCR, G prote<strong>in</strong>-coupled receptor; GRP, gastr<strong>in</strong>-releas<strong>in</strong>g peptide; IP,<strong>in</strong>terven<strong>in</strong>g peptide; JNK, Jun N-term<strong>in</strong>al k<strong>in</strong>ase; MNNG, N-methyl-Nnitro-N-nitroguanid<strong>in</strong>e;mTOR, mammalian target <strong>of</strong> rapamyc<strong>in</strong>; MTX,methotrexate; NPY, neuropeptide Y; NT, neurotens<strong>in</strong>; NTR, NT receptor;PGDP, proglucagon-derived peptide; PI3K, phosphatidyl<strong>in</strong>ositol3-k<strong>in</strong>ase; PP, pancreatic polypeptide; PT, gastr<strong>in</strong>oma; PYY, peptide YY;SAPK, stress-activated prote<strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>ase; SCLC, small cell lung cancer;TPN, total parenteral nutrition; TVF, Thiry-Vella fistula.I. IntroductionGASTROINTESTINAL (GI) HORMONES are chemicalmessengers that regulate <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al <strong>and</strong> pancreaticfunction, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g regulation <strong>of</strong> secretion, motility, absorption,digestion, <strong>and</strong> cell proliferation. These hormones aresecreted by endocr<strong>in</strong>e cells, which are widely distributedthroughout <strong>the</strong> GI mucosa <strong>and</strong> pancreas. Although <strong>the</strong>sehormones were <strong>in</strong>itially described as solely endocr<strong>in</strong>e products,subsequent studies have shown that <strong>the</strong>y can act <strong>in</strong> anautocr<strong>in</strong>e or paracr<strong>in</strong>e fashion to affect cellular function. GIhormones may also serve as transmitt<strong>in</strong>g agents for nervousimpulses discharged <strong>in</strong>to blood vessels after nervous stimulation<strong>in</strong> a true neurocr<strong>in</strong>e fashion. This review will focuson <strong>the</strong> trophic effects <strong>of</strong> GI hormones on nonneoplastic <strong>and</strong>neoplastic tissues.II. GI <strong>Hormones</strong>The trophic GI hormones that have been best characterized<strong>and</strong> will be discussed <strong>in</strong> this review <strong>in</strong>clude gastr<strong>in</strong>, cholecystok<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>(CCK), bombes<strong>in</strong> (BBS)/gastr<strong>in</strong>-releas<strong>in</strong>g peptide(GRP), neurotens<strong>in</strong> (NT), peptide YY (PYY), glucagon-likepeptide (GLP)-2, <strong>and</strong> somatostat<strong>in</strong>. These hormones sharemany <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same attributes, such as <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> largeprecursor molecules, multiple active is<strong>of</strong>orms, multiplemembrane-bound receptors, <strong>and</strong> signal<strong>in</strong>g through multiple<strong>in</strong>tracellular pathways. The distribution, syn<strong>the</strong>sis, <strong>and</strong> secretion<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se hormones as well as <strong>the</strong> receptors <strong>and</strong> signal<strong>in</strong>gpathways that mediate <strong>the</strong> hormone response will bebriefly described.A. GI hormone distribution, syn<strong>the</strong>sis, <strong>and</strong> secretion1. Gastr<strong>in</strong>. The presence <strong>of</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong> was postulated <strong>in</strong> 1906 byEdk<strong>in</strong>s (1), but it was not until 1938 that Komarov (2) prepareduseful, histam<strong>in</strong>e-free antral extracts <strong>of</strong> this gastricstimulant. Gastr<strong>in</strong> is now firmly established as <strong>the</strong> physiologicalregulator <strong>of</strong> gastric acid secretion <strong>and</strong> an importantregulator <strong>of</strong> gastric mucosal cell proliferation (3). The majorsite <strong>of</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong> syn<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>and</strong> secretion is <strong>the</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong>-conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gcell (G cell) <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> antropyloric mucosa (4–6). O<strong>the</strong>rm<strong>in</strong>or sites <strong>of</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong> production <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>the</strong> endocr<strong>in</strong>e cells571Downloaded from edrv.endojournals.org by on July 16, 2007

572 Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Reviews, October 2003, 24(5):571–599 Thomas et al. • <strong>Gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al</strong> <strong>Hormones</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Proliferation</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pancreas (7), pituitary (8), <strong>and</strong> extraantral G cells (9).Gastr<strong>in</strong> release is stimulated by food components, particularlyaromatic am<strong>in</strong>o acids <strong>and</strong> am<strong>in</strong>e derivatives <strong>of</strong> am<strong>in</strong>oacids, <strong>and</strong> is <strong>in</strong>hibited by lum<strong>in</strong>al acid (10).Human progastr<strong>in</strong>, <strong>the</strong> precursor <strong>of</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong>, consists <strong>of</strong> a21-am<strong>in</strong>o-acid signal peptide, a 37-am<strong>in</strong>o-acid N-term<strong>in</strong>alextension, <strong>the</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong>-34 sequence, <strong>and</strong> a 9-am<strong>in</strong>o-acid C-term<strong>in</strong>al extension (3, 10). In antral G cells, progastr<strong>in</strong> isstored <strong>and</strong> processed <strong>in</strong>to secretory granules, <strong>and</strong> N-term<strong>in</strong>al<strong>and</strong> C-term<strong>in</strong>al extensions are removed by prohormone convertases.The C-term<strong>in</strong>al basic am<strong>in</strong>o acids are sequentiallyremoved by a carboxypeptidase, which results <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> formation<strong>of</strong> glyc<strong>in</strong>e-extended G34 (G34-gly). G34-gly is amidatedby peptidyl glyc<strong>in</strong>e -amidat<strong>in</strong>g monooxygenase t<strong>of</strong>orm G34-NH 2 (G-34) or cleaved at <strong>in</strong>ternal lys<strong>in</strong>e/lys<strong>in</strong>eresidues to form G-17-gly (referred to as G-gly) (10). Recentstudies have demonstrated that <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> G-17-NH 2(also known as gastr<strong>in</strong> or G-17) arises from <strong>the</strong> conversion <strong>of</strong>G34-NH 2 to G-17-NH 2 , ra<strong>the</strong>r than by amidation <strong>of</strong> G-gly,suggest<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> conversion <strong>of</strong> G-gly to amidated G-17 isblocked <strong>and</strong> that G-gly is a term<strong>in</strong>al, secondary end-product<strong>of</strong> progastr<strong>in</strong> process<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> normal antral G cells (10, 11). Thisis contrasted by evidence <strong>in</strong> colon cancer cells that gastr<strong>in</strong>bypasses <strong>the</strong> process<strong>in</strong>g mach<strong>in</strong>ery <strong>and</strong> is expressed <strong>in</strong>larger, unprocessed forms that are transported <strong>in</strong> secretoryvesicles <strong>and</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>uously fused with <strong>the</strong> plasma membrane<strong>and</strong> released (11).2. CCK. CCK was described <strong>in</strong> 1928 by Ivy <strong>and</strong> Oldberg (12)as a contam<strong>in</strong>ant <strong>in</strong> impure secret<strong>in</strong> preparations. These impuritieswere noted to produce gallbladder contraction <strong>in</strong>dogs <strong>and</strong> cats. In 1943, Harper <strong>and</strong> Raper (13) identified as<strong>in</strong>gle agent extracted from <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al samples that possessedpancreatic-stimulat<strong>in</strong>g activity. After complete purification<strong>and</strong> sequenc<strong>in</strong>g, it was determ<strong>in</strong>ed that this s<strong>in</strong>gle compound,CCK, was responsible for gallbladder contraction<strong>and</strong> pancreatic enzyme secretion (14). O<strong>the</strong>r actions <strong>of</strong> CCK<strong>in</strong>clude <strong>in</strong>hibition <strong>of</strong> gastric empty<strong>in</strong>g, stimulation <strong>of</strong> bowelmotility, potentiation <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong> secretion, <strong>and</strong> trophic effectson <strong>the</strong> pancreas <strong>and</strong> GI mucosa (3). CCK release is stimulatedby fats, prote<strong>in</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> am<strong>in</strong>o acids.CCK is produced by endocr<strong>in</strong>e cells <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gut (primarilyduodenum <strong>and</strong> jejunum), <strong>the</strong> neurons <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bra<strong>in</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>peripheral nervous system <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> GI tract (15–18). Ultrastructuralstudies demonstrate that <strong>the</strong> cells are identical to I cells<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> human <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e (19). CCK neurons are found <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>myenteric plexus, submucosal plexus, <strong>and</strong> circular musclelayers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> distal <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> colon (9). PostganglionicCCK nerve fibers are found <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> pancreas surround<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>islets <strong>of</strong> Langerhans (20). Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, although CCK hasnot been found <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic neurons <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> stomach <strong>and</strong>duodenum, CCK cells are <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> celiac plexus <strong>and</strong> can befound <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> vagus nerve, especially after <strong>in</strong>jury (21, 22).The molecular forms <strong>of</strong> CCK are diverse <strong>and</strong> appear to betissue-specific (23, 24). The most abundant form <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> bra<strong>in</strong>appears to be CCK-8, although significant amounts <strong>of</strong> largercarboxy-amidated forms like CCK-33, CCK-58, <strong>and</strong> CCK-83have been isolated.3. BBS/GRP. BBS, a tetradecapeptide orig<strong>in</strong>ally isolated from<strong>the</strong> sk<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> frog Bomb<strong>in</strong>a bomb<strong>in</strong>a, is analogous to mammalianGRP (24). In general, BBS/GRP may be thought <strong>of</strong> asa universal on-switch with predom<strong>in</strong>antly stimulatory effects.BBS/GRP stimulates <strong>the</strong> release <strong>of</strong> all GI hormones,<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al <strong>and</strong> pancreatic secretion, <strong>and</strong> motility (24). Themost important functions <strong>of</strong> BBS/GRP are antral gastr<strong>in</strong>release <strong>and</strong> stimulation <strong>of</strong> gastric acid secretion (25, 26). Thispeptide also stimulates growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> GI mucosa <strong>and</strong> pancreas(24).BBS/GRP-like immunoreactivity is widely distributedthroughout <strong>the</strong> GI tract <strong>of</strong> rats, gu<strong>in</strong>ea pigs, dogs, <strong>and</strong> humans(27–31), predom<strong>in</strong>antly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> neuronal populations <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> gut. GRP is most abundant <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> stomach, with GRPpositivecells <strong>and</strong> fibers <strong>in</strong>nervat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> oxyntic <strong>and</strong> antralmucosa <strong>and</strong> circular muscle.4. NT. NT, a tridecapeptide orig<strong>in</strong>ally isolated from bov<strong>in</strong>ehypothalamus (32), is localized ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> central nervoussystem (predom<strong>in</strong>antly hypothalamus <strong>and</strong> pituitary) <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>endocr<strong>in</strong>e cells (N cells) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> jejunal <strong>and</strong> ileal mucosa (33,34). NT is released <strong>in</strong> response to <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong>tralum<strong>in</strong>al fats(35, 36) <strong>and</strong> has numerous functions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> GI tract, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gstimulation <strong>of</strong> pancreatic secretion (37), <strong>in</strong>hibition <strong>of</strong> gastric<strong>and</strong> small bowel motility (38), facilitation <strong>of</strong> fatty acid translocationfrom <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al lumen (39), <strong>and</strong> growth stimulation<strong>of</strong> various GI tissues (34, 40–43).NT is produced from a s<strong>in</strong>gle precursor, preproneurotens<strong>in</strong>,that conta<strong>in</strong>s both NT 1–13 <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> related peptide,neuromed<strong>in</strong> N. Neuromed<strong>in</strong> N comprises <strong>the</strong> C-term<strong>in</strong>alportion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> proneurotens<strong>in</strong> peptide after NT is removed.NT 1–13, <strong>the</strong> major product <strong>of</strong> proneurotens<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ileum<strong>and</strong> bra<strong>in</strong> (44), is cleaved at or soon after secretion at <strong>the</strong>dibasic arg 8 -arg 9 residues, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>active degradationproduct NT 1–8 <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> biologically active NT 9–13.Substance P, muscar<strong>in</strong>ic agonists (carbachol), catecholam<strong>in</strong>es,<strong>and</strong> BBS/GRP stimulate NT release, suggest<strong>in</strong>g that a complex<strong>in</strong>terplay <strong>of</strong> neural, endocr<strong>in</strong>e, <strong>and</strong> lum<strong>in</strong>al mechanisms is responsiblefor NT release <strong>and</strong> physiological function<strong>in</strong>g (45–47).5. PYY. PYY, a 36-am<strong>in</strong>o-acid peptide, is homologous to twoo<strong>the</strong>r regulatory peptides, pancreatic polypeptide (PP) <strong>and</strong>neuropeptide Y (NPY) (3). Both <strong>the</strong> rat <strong>and</strong> human PYY geneshave been isolated <strong>and</strong> characterized (48, 49). The conservedstructural organization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> genes encod<strong>in</strong>g PYY, NPY, <strong>and</strong>PP suggests that each gene is derived from duplication <strong>of</strong> acommon ancestral gene. The biological actions <strong>of</strong> PYY <strong>in</strong>clude<strong>in</strong>hibition <strong>of</strong> pancreatic bicarbonate secretion <strong>and</strong> contraction<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gallbladder (50). In addition, PYY <strong>in</strong>hibitsgastric empty<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al transit <strong>and</strong> has been postulatedas an agent that contributes to <strong>the</strong> ileal brake phenomenon,a negative-feedback mechanism that promotes <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>alabsorption (3). PYY can also stimulate growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> GImucosa (51).PYY, NPY, <strong>and</strong> PP are syn<strong>the</strong>sized as prepropeptides consist<strong>in</strong>g<strong>of</strong> a signal peptide followed by <strong>the</strong> 36-residue activepeptide, a cleavage-sequence Gly-Lys-Arg, <strong>and</strong> a carboxyterm<strong>in</strong>alflank<strong>in</strong>g peptide (52, 53). Dur<strong>in</strong>g process<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong>precursor is cleaved at <strong>the</strong> carboxy term<strong>in</strong>al by a specificprohormone convertase. The Lys-Arg sequences are <strong>the</strong>nlysed by a carboxypeptidase, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> carboxy-term<strong>in</strong>al tyros<strong>in</strong>eis amidated. Typical enteroendocr<strong>in</strong>e cells, with longDownloaded from edrv.endojournals.org by on July 16, 2007

Thomas et al. • <strong>Gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al</strong> <strong>Hormones</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Proliferation</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Reviews, October 2003, 24(5):571–599 573basal processes, are visualized by immunohistochemistry <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> mucosa <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ileum, colon, <strong>and</strong> rectum (54).6. GLP. GLPs are a group <strong>of</strong> peptides known as <strong>the</strong> enteroglucagons.The enteroglucagons are products <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> samegene that produces glucagon <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> pancreatic -cell (3). The<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al L cell produces two elongated glucagons, glicent<strong>in</strong><strong>and</strong> oxyntomodul<strong>in</strong>, <strong>and</strong> both <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> enteroglucagons, GLP-1<strong>and</strong> GLP-2 (55). Both GLP-1 <strong>and</strong> GLP-2 have effects on nutrientabsorption <strong>and</strong> GI tract physiology; however, <strong>the</strong>setwo peptides have dist<strong>in</strong>ct roles. GLP-1 has a significanteffect on blood glucose levels, lower<strong>in</strong>g blood glucose levelsvia stimulation <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong> secretion (55), thus suggest<strong>in</strong>g thatGLP-1 may provide some <strong>the</strong>rapeutic benefit to patients withdiabetes. GLP-2 displays m<strong>in</strong>imal effects on glucose levels,but demonstrates potent trophic effects on <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al epi<strong>the</strong>lia(55).Both GLP-1 <strong>and</strong> GLP-2 are released when <strong>the</strong> L cell isexposed lum<strong>in</strong>ally to <strong>the</strong> products <strong>of</strong> a mixed meal (carbohydrateor fat) (55). L cells are most abundant <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mucosa<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ileum <strong>and</strong> colon; <strong>the</strong>y are <strong>the</strong> second most numerouspopulation <strong>of</strong> endocr<strong>in</strong>e cells <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> human <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e, afterenterochromaff<strong>in</strong> cells (56). Both GLP-1 <strong>and</strong> GLP-2 are rapidlycleaved by <strong>the</strong> exopeptidase dipeptidyl peptidase IV(55). Current concepts <strong>of</strong> L cell regulation <strong>in</strong>volve <strong>in</strong>tegration<strong>of</strong> hormonal messages from peptides, such as GRP <strong>and</strong> glucose-dependent<strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong>otropic polypeptide, <strong>and</strong> neuronalcontrol (55).7. Somatostat<strong>in</strong>. Somatostat<strong>in</strong> was isolated <strong>and</strong> characterizedfrom ov<strong>in</strong>e hypothalamic tissue dur<strong>in</strong>g a search for a GHreleas<strong>in</strong>gfactor (57). S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> identification <strong>and</strong> purification<strong>of</strong> somatostation-14, precursor forms <strong>of</strong> greater molecularweight, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g somatostat<strong>in</strong>-28, with somatostat<strong>in</strong>-14mak<strong>in</strong>g up <strong>the</strong> C term<strong>in</strong>us, <strong>and</strong> larger precursor forms <strong>of</strong> 120or more am<strong>in</strong>o acids have been identified (58). All <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>sepeptides exert biological activity but differ <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir relativepotency.Somatostat<strong>in</strong> has been detected <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nerves <strong>and</strong> cellbodies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> central <strong>and</strong> peripheral nervous systems, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> autonomic nervous system <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> GI tract <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>endocr<strong>in</strong>e-like D cells <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pancreatic islets <strong>and</strong> mucosa <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> stomach <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e (3). More than 90% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> somatostat<strong>in</strong>immunoreactivity <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> human gut is located with<strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> mucosal endocr<strong>in</strong>e D cells (58). In addition, somatostat<strong>in</strong>is located <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nerves <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> myenteric plexus. Somatostat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> pancreas is located <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> D cells at <strong>the</strong> periphery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>islets closely associated with <strong>the</strong> -cells (59).Somatostat<strong>in</strong> is a regulatory-<strong>in</strong>hibitory peptide, which, <strong>in</strong>contrast to BBS/GRP, may be considered as <strong>the</strong> universalendocr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong>f-switch. Somatostat<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>hibits <strong>the</strong> release <strong>of</strong> GH<strong>and</strong> somatomed<strong>in</strong> C <strong>and</strong> all known GI hormones (3). Somatostat<strong>in</strong>also <strong>in</strong>hibits gastric acid secretion <strong>and</strong> motility, <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>alabsorption, <strong>and</strong> pancreatic bicarbonate <strong>and</strong> enzymesecretion, <strong>and</strong> selectively decreases splanchnic <strong>and</strong> portalblood flow (60). In addition, somatostat<strong>in</strong> can <strong>in</strong>hibit <strong>the</strong>growth <strong>of</strong> normal <strong>and</strong> neoplastic tissues (61–67).B. GI hormone receptors <strong>and</strong> signal transduction pathways1. Receptors. GI hormone-stimulated signal transduction occurswith <strong>the</strong> b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> hormones to <strong>the</strong>ir cognate cell surfacereceptor, <strong>the</strong> G prote<strong>in</strong>-coupled receptor (GPCR) (68).The GI hormone-GPCRs have <strong>the</strong> typical structural features<strong>of</strong> G prote<strong>in</strong> b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g seven-transmembrane receptors (Fig. 1).The receptors for gastr<strong>in</strong>, CCK, BBS/GRP, NT, PYY, GLP-2,<strong>and</strong> somatostat<strong>in</strong>, which are respectively, <strong>the</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong>/CCK-Breceptor, CCK-A receptor, GRP receptor, <strong>the</strong> NT receptor(NTR), NPY receptor, GLP-2 receptor, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> somatostat<strong>in</strong>receptor (five subtypes), are all GPCRs (3, 55). GPCRs regulatea number <strong>of</strong> physiological processes, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g proliferation,growth, <strong>and</strong> development (68). It was orig<strong>in</strong>allythought that, <strong>in</strong> order for GPCR signal<strong>in</strong>g to occur, specific<strong>in</strong>teractions between <strong>the</strong> GI hormone <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> receptor werenecessary to produce conformational changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> receptor<strong>and</strong> stimulate <strong>in</strong>tracellular signal transduction networks.However, recent studies suggest a more complex regulation<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> GPCRs through: 1) dimerization with <strong>the</strong>mselves <strong>and</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r receptors; 2) activation <strong>of</strong> differ<strong>in</strong>g G prote<strong>in</strong>s; 3) <strong>in</strong>ternalization<strong>and</strong> desensitization; <strong>and</strong> 4) ability to change <strong>in</strong>conformation <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>teractions with empty, or <strong>in</strong>active, receptors(69). It is suggested that this complicated mechanism<strong>of</strong> regulation allows peptides to <strong>in</strong>teract with GPCRs to stimulatediverse <strong>in</strong>tracellular signal<strong>in</strong>g pathways <strong>and</strong> ultimatelyaffect multiple physiological functions, depend<strong>in</strong>g on celltype.2. Signal transduction pathways. The seven transmembranespann<strong>in</strong>g-helical doma<strong>in</strong>s function as lig<strong>and</strong>-regulatedguan<strong>in</strong>e nucleotide exchange factors for <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tracellular heterotrimericG prote<strong>in</strong>s (68). Heterotrimeric G prote<strong>in</strong>s arecomposed <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> products <strong>of</strong> three gene families encod<strong>in</strong>g -,-, <strong>and</strong> -subunits (68). The agonist-activated GPCR catalyzes<strong>the</strong> exchange <strong>of</strong> GTP for GDP bound to <strong>the</strong> G-subunit,as well as <strong>the</strong> dissociation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> GTP-G from its cognateG dimer (Fig. 2A) (68). The activated GTP-G- <strong>and</strong> Gsubunits,<strong>in</strong> turn, regulate <strong>the</strong> activity <strong>of</strong> various <strong>in</strong>tracellulareffector prote<strong>in</strong>s such as phospholipases, adenylyl cyclases,prote<strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>ases, membrane ion channels, <strong>and</strong> members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Ras family <strong>of</strong> GTP-b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong>s (68). In addition, basedon structural similarities, <strong>the</strong> 20 identified G-subunits havebeen divided <strong>in</strong>to four subfamilies <strong>and</strong> assigned an effectorpathway based on current evidence. The four are: 1) <strong>the</strong>cholera tox<strong>in</strong>-sensitive () subunits that stimulate adenylcyclase <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>crease cAMP levels; 2) <strong>the</strong> pertussis tox<strong>in</strong>sensitive( i/o ) subunits that <strong>in</strong>hibit adenylyl cyclase activity;3) <strong>the</strong> pertussis tox<strong>in</strong>-<strong>in</strong>sensitive ( q/11/14 ) subunits that stimulatemembrane phospholipases; <strong>and</strong> 4) <strong>the</strong> 12/13 subfamilythat l<strong>in</strong>ks GPCR to <strong>the</strong> Ras-related GTP-b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong>, Rho(68). Additionally, 12 G- <strong>and</strong> 6-G subunits have been identified;<strong>the</strong>se -dimers have been l<strong>in</strong>ked to <strong>the</strong> signal<strong>in</strong>gmolecules phosphatidyl<strong>in</strong>ositol 3-k<strong>in</strong>ase (PI3K) <strong>and</strong> selectforms <strong>of</strong> adenylyl cyclase <strong>and</strong> receptor k<strong>in</strong>ases (68).Among <strong>the</strong> multiple <strong>in</strong>tracellular signal<strong>in</strong>g pathways thatmediate <strong>the</strong> proliferative effects <strong>of</strong> GPCRs, a family <strong>of</strong> relatedser<strong>in</strong>e-threon<strong>in</strong>e k<strong>in</strong>ases, collectively known as ERKs orMAPKs, appear to play a central role (70). After phosphorylationby <strong>the</strong>ir immediate upstream MAPK k<strong>in</strong>ase, members<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> MAPK family translocate to <strong>the</strong> nucleus, where<strong>the</strong>y phosphorylate transcription factors, thus regulat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>expression <strong>of</strong> genes that control growth (71). <strong>Hormones</strong> actas lig<strong>and</strong>s to eventually activate p42 <strong>and</strong> p44 MAPK (Fig. 2B)Downloaded from edrv.endojournals.org by on July 16, 2007

574 Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Reviews, October 2003, 24(5):571–599 Thomas et al. • <strong>Gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al</strong> <strong>Hormones</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Proliferation</strong>FIG. 1. GPCR: am<strong>in</strong>o acid sequence for <strong>the</strong> structure <strong>of</strong> typical GPCR <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> seven-transmembrane doma<strong>in</strong>s. Am<strong>in</strong>o acid sequences<strong>of</strong> CCK-B (A) <strong>and</strong> CCK-A (B) receptors <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g similar seven-transmembrane structure <strong>and</strong> about 50% am<strong>in</strong>o acid identity. Identical am<strong>in</strong>oacids are shaded. The NH 2 portion is extracellular, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> COOH portion is <strong>in</strong>tracellular. [From J. H. Walsh: Physiology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al</strong>Tract, Vol 1, pp 1–128, 1994 (3). © Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott Williams & Wilkens.](72). The mechanism by which this occurs <strong>in</strong>volves a complex<strong>in</strong>terplay <strong>of</strong> several known nonreceptor k<strong>in</strong>ases <strong>and</strong> receptork<strong>in</strong>ases. The ability <strong>of</strong> tyros<strong>in</strong>e k<strong>in</strong>ase <strong>in</strong>hibitors to reduce <strong>the</strong>activation <strong>of</strong> MAPK by GPCR (73) <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> rapid tyros<strong>in</strong>ephosphorylation <strong>of</strong> Shc (Src homology <strong>and</strong> collagen) afterGPCR stimulation with <strong>the</strong> consequent formation <strong>of</strong> Shc-Downloaded from edrv.endojournals.org by on July 16, 2007

Thomas et al. • <strong>Gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al</strong> <strong>Hormones</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Proliferation</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Reviews, October 2003, 24(5):571–599 575FIG. 2. Diversity <strong>of</strong> GPCRs. A, <strong>Hormones</strong> use GPCRs to stimulate cytoplasmic <strong>and</strong> nuclear targets through heterotrimeric G prote<strong>in</strong>-dependent<strong>and</strong> -<strong>in</strong>dependent pathways. B, Multiple pathways l<strong>in</strong>k GPCRs to MAPK. Activated MAPK translocates to <strong>the</strong> nucleus <strong>and</strong> phosphorylatesnuclear prote<strong>in</strong>s, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g transcription factors, <strong>the</strong>reby regulat<strong>in</strong>g gene expression. C, Novel signal<strong>in</strong>g pathways that connect GPCRs to JNK,p38 is<strong>of</strong>orms, <strong>and</strong> big mitogen-activated k<strong>in</strong>ase 1 (ERK5): molecules that l<strong>in</strong>k GPCRs to <strong>the</strong> different members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> MAPK family. EPAC,Exchange prote<strong>in</strong> activated by cAMP; FAK, focal adhesion k<strong>in</strong>ase; GAP, GTPase-activat<strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong>; GEF, guan<strong>in</strong>e nucleotide exchange factor;GRF, guan<strong>in</strong>e-nucleotide releas<strong>in</strong>g factor; MEK <strong>and</strong> MKK, MAPK k<strong>in</strong>ase; MEKK, MAPK k<strong>in</strong>ase k<strong>in</strong>ase; MLK, mixed l<strong>in</strong>eage k<strong>in</strong>ase; PKA,prote<strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>ase A; PLC, phospholipase C; PYK2, prol<strong>in</strong>e-rich tyros<strong>in</strong>e k<strong>in</strong>ase 2; RGS, regulator <strong>of</strong> G prote<strong>in</strong> signal<strong>in</strong>g; RTK, receptor tyros<strong>in</strong>ek<strong>in</strong>ase. [Adapted with permission from M. J. Mar<strong>in</strong>issen <strong>and</strong> J. S. Gutk<strong>in</strong>d: Trends Pharmacol Sci 22:368–376, 2001 (68). ©Elsevier Science.]Downloaded from edrv.endojournals.org by on July 16, 2007

576 Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Reviews, October 2003, 24(5):571–599 Thomas et al. • <strong>Gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al</strong> <strong>Hormones</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Proliferation</strong>Grb2 (growth factor receptor-bound 2) complexes (74) provideevidence that tyros<strong>in</strong>e k<strong>in</strong>ases l<strong>in</strong>k GPCRs to <strong>the</strong> Ras-MAPK pathway.Additionally, GPCRs l<strong>in</strong>k to <strong>the</strong> Jun N-term<strong>in</strong>al k<strong>in</strong>ase(JNK), p38 MAPK, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> big mitogen-activated k<strong>in</strong>ase 1 orERK5 pathways (Fig. 2C) (68). JNK, also termed stress-activatedprote<strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>ase (SAPK), is structurally related toMAPK, but <strong>the</strong> pathways used by GPCRs to activate <strong>the</strong>sek<strong>in</strong>ases are different. Activated Rac <strong>and</strong> Cdc42 affect JNKactivation through stimulation from free -dimers <strong>and</strong> G 12<strong>and</strong> G 13 .Four p38 MAPKs have been described, p38 (CSBP-1), p38, p38 (ERK6 or SAPK3), <strong>and</strong> p38 (SAPK4) (75). Yamauchiet al. (76) demonstrated that G q <strong>and</strong> dimers activatep38. Two nonreceptor tyros<strong>in</strong>e k<strong>in</strong>ases, Btk <strong>and</strong> Src (77, 78),have been associated with this process. ERK5 can be activatedby oxidative stress <strong>and</strong> plays a role <strong>in</strong> early geneexpression (79). GPCRs can potently stimulate ERK5 througha mechanism that <strong>in</strong>volves G q <strong>and</strong> G 13 , <strong>in</strong>dependent <strong>of</strong>Rho, Rac1, <strong>and</strong> Cdc42 (80, 81). Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, ERK5 regulatesearly gene expression through <strong>the</strong> phosphorylation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>transcription factor, myocyte enhancer factor 2 (80).The molecular mechanisms through which GPCRs transducesignals are complex <strong>and</strong> likely <strong>in</strong>volve multiple signalpathways. In addition, <strong>the</strong> signal<strong>in</strong>g pathways are likelycell-specific, which may expla<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> diverse physiologicalfunctions controlled by GI hormones rang<strong>in</strong>g from regulation<strong>of</strong> secretion, mobility, <strong>and</strong>, <strong>in</strong> some <strong>in</strong>stances, growthdepend<strong>in</strong>g upon <strong>the</strong> target tissue.III. <strong>Proliferation</strong> <strong>and</strong> Repair <strong>of</strong> NonneoplasticTissues by GI <strong>Hormones</strong>GI hormones can alter proliferation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> normal gut <strong>and</strong>pancreas. In this section, we will review <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>stimulatory hormones gastr<strong>in</strong>, CCK, BBS/GRP, NT, PYY,<strong>and</strong> GLP-2 <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>hibitory hormone, somatostat<strong>in</strong>, on <strong>the</strong>growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pancreas <strong>and</strong> mucosa <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> GI tract.A. Gastr<strong>in</strong>Gastr<strong>in</strong> is <strong>the</strong> GI hormone that has been best characterizedfor its trophic effects. In addition to stimulat<strong>in</strong>g acid secretionfrom gastric parietal cells, gastr<strong>in</strong> is <strong>the</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle most importanttrophic hormone <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> stomach (82).1. Stomach. The trophic effect <strong>of</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong> was <strong>in</strong>itially describedmore than 30 yr ago <strong>in</strong> two separate reports. Johnsonet al. (83) <strong>and</strong> Crean et al. (84) demonstrated that pentagastr<strong>in</strong>,a syn<strong>the</strong>tic gastr<strong>in</strong> analog conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> active carboxylterm<strong>in</strong>altetrapeptide, <strong>in</strong>creased prote<strong>in</strong> syn<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>and</strong> parietalcell mass <strong>in</strong> rats. These results were fur<strong>the</strong>r confirmedus<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> natural amidated gastr<strong>in</strong>s, G-17 <strong>and</strong> G-34. G-17 <strong>and</strong>G-34 produced maximal stimulation <strong>of</strong> DNA syn<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>oxyntic mucosa, duodenum, <strong>and</strong> colon at doses <strong>of</strong> 13.5 <strong>and</strong>6.75 nmol/kg, respectively.In <strong>the</strong> stomach, <strong>the</strong> oxyntic, acid-secret<strong>in</strong>g mucosa <strong>and</strong>enterochromaff<strong>in</strong>-like cells (cells that produce histam<strong>in</strong>escritical to parietal cell acid production) are particularly sensitiveto <strong>the</strong> trophic actions <strong>of</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong> (85). The removal <strong>of</strong>endogenous gastr<strong>in</strong>, by antral resection, results <strong>in</strong> mucosalatrophy that can be prevented by adm<strong>in</strong>ister<strong>in</strong>g exogenousgastr<strong>in</strong>.Overexpression <strong>of</strong> ei<strong>the</strong>r unprocessed gastr<strong>in</strong>s or <strong>the</strong> amidatedgastr<strong>in</strong>s (G-17 <strong>and</strong> G-34) <strong>in</strong> transgenic mice results <strong>in</strong>a 2-fold elevation <strong>in</strong> serum-amidated gastr<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> producesmarked thicken<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> oxyntic mucosa with <strong>in</strong>creasedbromodeoxyurid<strong>in</strong>e (BrdU) label<strong>in</strong>g, represent<strong>in</strong>g an 85%<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> cells undergo<strong>in</strong>g proliferation (86, 87). These f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsare fur<strong>the</strong>r supported by results <strong>in</strong> athymic nude micebear<strong>in</strong>g xenografts <strong>of</strong> a transplanted human gastr<strong>in</strong>oma (PT)demonstrat<strong>in</strong>g gastric <strong>and</strong> duodenal mucosal hyperplasia(Fig. 3) (Ref. 88).In gastr<strong>in</strong>-deficient mice (89, 90), a 35% decrease <strong>in</strong> parietalcell mass with no decrease <strong>in</strong> basal fundic proliferation ratesis noted, compared with wild-type control mice, suggest<strong>in</strong>gthat, although gastr<strong>in</strong> can stimulate proliferation, it is notnecessarily required for basal proliferation. Taken toge<strong>the</strong>r,<strong>the</strong>se experimental results, us<strong>in</strong>g different <strong>in</strong> vivo models,<strong>in</strong>dicate that amidated gastr<strong>in</strong> can stimulate proliferation <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> oxyntic mucosa, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased parietal <strong>and</strong> enterochromaff<strong>in</strong>-likecell production.2. Small <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e. The role <strong>of</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong> as a stimulant for smallbowel mucosal growth is less clear. Johnson et al. (83) showedthat [ 3 H]thymid<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>corporation <strong>and</strong> DNA syn<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>of</strong> ratduodenal tissues were significantly <strong>in</strong>creased by pentagas-FIG. 3. Human PT xenografts produce gastr<strong>in</strong>, result<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> gastric <strong>and</strong> duodenal mucosal growth. A, Stomachsopened along greater curvature from mice with PTtumors (top) <strong>and</strong> controls (bottom). B, Effects <strong>of</strong> PT on<strong>the</strong> mouse gastric fundus (n 5 PT mice; n 10 controlmice; *, P 0.05). [Adapted with permission from J. R.Upp Jr. et al.: Surgery 104:1037–1045, 1988 (88). ©Mosby, Inc.]Downloaded from edrv.endojournals.org by on July 16, 2007

Thomas et al. • <strong>Gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al</strong> <strong>Hormones</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Proliferation</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Reviews, October 2003, 24(5):571–599 577tr<strong>in</strong>, G-17, <strong>and</strong> G-34 adm<strong>in</strong>istration. Schwartz <strong>and</strong> Storozuk(91) found that exogenous gastr<strong>in</strong> (13.5 nmol/kgd) enhancedgrowth <strong>of</strong> jejunoileal segments obta<strong>in</strong>ed from 19- to20-d gestation fetal rats transplanted sc <strong>in</strong> adult rats. Inaddition, adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong> enhanced <strong>the</strong> absorption<strong>of</strong> galactose <strong>and</strong> glyc<strong>in</strong>e, suggest<strong>in</strong>g that gastr<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>creasesfunctional activity as well as growth. Subsequent studies,however, us<strong>in</strong>g both pentagastr<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> natural G-17 havefailed to demonstrate significant trophic effects <strong>of</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> small bowel (jejunum <strong>and</strong> ileum) mucosa <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> adult ratas measured by v<strong>in</strong>crist<strong>in</strong>e-arrested metaphase (92). An explanationfor <strong>the</strong>se differ<strong>in</strong>g results is not entirely clear butmay perta<strong>in</strong> to different experimental measures <strong>of</strong> proliferation.Therefore, although <strong>the</strong> trophic effects <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> oxyntic<strong>and</strong> duodenal mucosa are well established, <strong>the</strong> trophic effect<strong>of</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g small <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e is currently consideredm<strong>in</strong>imal, at best.3. Colon. Similar to <strong>the</strong> small bowel, evidence for a trophiceffect <strong>of</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> colon is limited. In earlier studies byJohnson (93), adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> natural porc<strong>in</strong>e gastr<strong>in</strong>s stimulatedDNA syn<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> colon. In contrast, hypergastremia,<strong>in</strong>duced through acid blockade by ei<strong>the</strong>r omeprazoleadm<strong>in</strong>istration (94) or fundectomy (95), failed to produceproliferation <strong>of</strong> ei<strong>the</strong>r normal colon or <strong>the</strong> colon carc<strong>in</strong>omacells transplanted from an orig<strong>in</strong>al 1,2-dimethylhydraz<strong>in</strong>e<strong>in</strong>ducedadenocarc<strong>in</strong>oma.As opposed to results us<strong>in</strong>g amidated gastr<strong>in</strong>, recent experimentsus<strong>in</strong>g G-gly demonstrate colonic proliferation,spark<strong>in</strong>g renewed <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> a role for gastr<strong>in</strong> precursorproducts <strong>in</strong> colonic growth. Koh et al. (96) generated micethat overexpress progastr<strong>in</strong> truncated at glyc<strong>in</strong>e-72 (MTI/G-GLY), which demonstrates elevated serum <strong>and</strong> mucosallevels <strong>of</strong> G-gly compared with wild-type mice. MTI/G-GLYmice display a 43% <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> colonic mucosal thickness <strong>and</strong>a 41% <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> goblet cells per crypt.Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> G-gly to gastr<strong>in</strong>-deficientmice resulted <strong>in</strong> a 10% <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> colonic mucosal thickness<strong>and</strong> an 81% <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> colonic proliferation (as measured byBrdU) when compared with control mice. Thus, <strong>the</strong>se data,us<strong>in</strong>g exogenous adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>and</strong> genetic mouse models,demonstrate that G-gly is a potent stimulator <strong>of</strong> colonicproliferation.4. Pancreas. The role <strong>of</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> normal pancreatic growthis also believed to be stimulatory. In two separate studies,<strong>in</strong>vestigators <strong>in</strong> our laboratory have demonstrated small,albeit significant, <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> pancreatic growth. In <strong>the</strong> firststudy, young adult rats were given pentagastr<strong>in</strong>, NT, or BBS<strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation with an elemental diet (ED) (33). Pentagastr<strong>in</strong>at a maximal dose, 250 g/kg, <strong>in</strong>creased pancreatic weightcompared with control rats. In <strong>the</strong> second study, pentagastr<strong>in</strong>(100 g/kg) was given to young (3-month-old), adult(12-month-old), <strong>and</strong> aged (24-month-old) rats (97). In youngrats, pentagastr<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased pancreatic weight, DNA, RNA,<strong>and</strong> prote<strong>in</strong> content. In adult rats, however, pentagastr<strong>in</strong>only produced <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> RNA content, whereas aged ratsshowed no trophic effect. These results suggest that <strong>the</strong> effects<strong>of</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong> on pancreatic growth are dependent uponage. Fur<strong>the</strong>r support for a stimulatory effect <strong>of</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong> onpancreatic cells is provided by <strong>in</strong> vitro studies us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> ratpancreatic ac<strong>in</strong>ar cancer cell l<strong>in</strong>e, AR42J, demonstrat<strong>in</strong>g thatgastr<strong>in</strong>s can <strong>in</strong>duce cellular proliferation through stimulation<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> c-fos transcription factor via prote<strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>ase C-dependent <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dependent mechanisms (98).In contrast, Chen et al. (99) <strong>in</strong>duced hypergastr<strong>in</strong>emia <strong>in</strong>male Sprague-Dawley rats by cont<strong>in</strong>uous <strong>in</strong>fusion <strong>of</strong> humanLeu 15-gastr<strong>in</strong>-17, by fundectomy, or by treatment with omeprazole.Gastr<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>fusion or omeprazole treatment did notaffect pancreatic weight <strong>and</strong> DNA content, whereas fundectomy<strong>in</strong>creased pancreatic weight <strong>and</strong> DNA content. Thesef<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs suggest that endogenous gastr<strong>in</strong> level variations donot directly play a role <strong>in</strong> pancreatic growth. Fur<strong>the</strong>r studiesare needed to conclusively establish <strong>the</strong> differences <strong>in</strong>gastr<strong>in</strong>-related hormonal signal<strong>in</strong>g affect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> growth <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> pancreas.B. CCKCCK, act<strong>in</strong>g through CCK-A receptors, is one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mostpotent secretagogues regulat<strong>in</strong>g pancreatic ac<strong>in</strong>ar cells (100).Additionally, CCK stimulates <strong>the</strong> growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pancreas <strong>in</strong>experimental studies (101, 102). However, evidence for CCKplay<strong>in</strong>g a major role <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> GI mucosa (stomach,small bowel, <strong>and</strong> colon) is limited.1. GI mucosa. Adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> CCK <strong>and</strong> secret<strong>in</strong> preventedatrophy <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> jejunum <strong>and</strong> ileum <strong>of</strong> dogs given total parenteralnutrition (TPN) as a sole nutrient source (103). Inaddition, adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se peptides <strong>in</strong>creased galactoseabsorption, suggest<strong>in</strong>g that CCK is a positive enterotrophicfactor for <strong>the</strong> gut. Weser et al. (104) provided additionalevidence that CCK alone, or <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation withsecret<strong>in</strong>, could prevent TPN-associated jejunal <strong>and</strong> ileal atrophy<strong>in</strong> rats. In subsequent studies, F<strong>in</strong>e et al. (105), us<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al bypass models, demonstrated that <strong>the</strong> trophic responsenoted by CCK <strong>and</strong> secret<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> small bowel was <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>direct result <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased pancreatobiliary secretion, as opposedto a direct stimulatory effect <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se peptides on <strong>the</strong>gut mucosa. Confirmation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> a direct effect <strong>of</strong> CCKon small bowel growth was provided by Stange et al. (106)us<strong>in</strong>g cultured rabbit jejunum <strong>and</strong> ileum preparations.2. Pancreas. In contrast, <strong>the</strong> trophic effects <strong>of</strong> CCK on <strong>the</strong>pancreas have been demonstrated by a number <strong>of</strong> experimentalmodels (107–113). In one study, <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> camostate(400 mg/kg), a potent <strong>in</strong>hibitor <strong>of</strong> tryps<strong>in</strong> (which blocksser<strong>in</strong>e proteases), were compared with <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> chronicexogenous adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> CCK-8 with or without adm<strong>in</strong>istration<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CCK-receptor antagonist, CR 1409 (114).Chronic (10-d) camostate feed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>creased pancreaticweight, prote<strong>in</strong>, <strong>and</strong> DNA content, which was associatedwith <strong>in</strong>creased CCK plasma levels. The adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong>exogenous CCK produced similar <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> pancreaticgrowth. The comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> camostate <strong>and</strong> CCK-8 producedan additive stimulatory effect on <strong>the</strong> pancreas. The CCKreceptorantagonist, CR 1409, completely abolished <strong>the</strong> trophiceffects <strong>of</strong> exogenous CCK-8 <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>hibited <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong>chronic camostate feed<strong>in</strong>g. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, CR 1409 alone decreasedpancreatic weight, DNA, <strong>and</strong> prote<strong>in</strong> content <strong>of</strong> rats.Additionally, o<strong>the</strong>r studies have substantiated <strong>and</strong> con-Downloaded from edrv.endojournals.org by on July 16, 2007

578 Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Reviews, October 2003, 24(5):571–599 Thomas et al. • <strong>Gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al</strong> <strong>Hormones</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Proliferation</strong>firmed a stimulatory effect <strong>of</strong> CCK on <strong>the</strong> pancreas (110–113).Taken toge<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>se studies provide clear evidence thatCCK is a potent stimulant for pancreatic growth.Recently, <strong>the</strong> cellular mechanisms regulat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> proliferativeeffect <strong>of</strong> CCK have been exam<strong>in</strong>ed. Similar to gastr<strong>in</strong>,CCK activates <strong>the</strong> MAPK cascade, lead<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> activation<strong>of</strong> ERK, JNK, <strong>and</strong> p38 MAPK <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> pancreas (115). In addition,<strong>the</strong>re is evidence that o<strong>the</strong>r signal<strong>in</strong>g pathways, suchas <strong>the</strong> PI3K-mTOR (mammalian target <strong>of</strong> rapamyc<strong>in</strong>)-p70 s6kpathway, are <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> CCK-stimulated mitogenesis <strong>and</strong>cellular proliferation (115). p70 s6k is physiologically importantfor phosphorylat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> small ribosomal subunit prote<strong>in</strong>S6, which was <strong>the</strong> first regulated phosphoprote<strong>in</strong> identified<strong>in</strong> pancreatic ac<strong>in</strong>ar cells (115), <strong>the</strong>reby facilitat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> syn<strong>the</strong>sis<strong>of</strong> RNA. Bragado et al. (116) demonstrated <strong>the</strong> phosphorylation<strong>and</strong> activation <strong>of</strong> p70 s6k <strong>in</strong> rat pancreatic ac<strong>in</strong>i byCCK, carbachol, <strong>and</strong> BBS, but not by cAMP, phorbol ester, orcalcium ionophore. This activation was blocked by rapamyc<strong>in</strong>,which <strong>in</strong>hibits mTOR, <strong>and</strong> by wortmann<strong>in</strong> (a PI3K <strong>in</strong>hibitor).In addition, <strong>the</strong> PI3K-mTOR pathway is known toplay a role <strong>in</strong> activat<strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong> syn<strong>the</strong>sis by phosphorylat<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong> eIF4E, <strong>the</strong> translation <strong>in</strong>itiation factorthat b<strong>in</strong>ds to <strong>the</strong> 7-methyl guanos<strong>in</strong>e cap at <strong>the</strong> 5 end <strong>of</strong> mosteukaryotic mRNA molecules (117). This b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong>,known as eIF4E-BP or PHAS-I, possesses multiple phosphorylatedsites <strong>and</strong>, when sufficiently phosphorylated, dissociatesfrom eIF4E, which can <strong>the</strong>n <strong>in</strong>teract with eIF4G (a scaffoldprote<strong>in</strong>) toge<strong>the</strong>r with eIF4A (a RNA helicase) to forma complex, known as eIF4F, <strong>and</strong> stimulate prote<strong>in</strong> syn<strong>the</strong>sis.CCK stimulation <strong>of</strong> rat pancreatic ac<strong>in</strong>i leads to PHAS-Iphosphorylation <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiation <strong>of</strong> a complex formation (118).C. BBS/GRPBBS/GRP stimulates pancreatic, gastric, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al secretion,<strong>and</strong> gut motility, smooth muscle contraction, <strong>and</strong>release <strong>of</strong> all gut hormones (29). In addition, BBS/GRP is apotent trophic factor for <strong>the</strong> GI tract <strong>and</strong> pancreas.1. Stomach. Lehy <strong>and</strong> colleagues (119, 120) reported that BBS,given orally or sc, stimulated <strong>the</strong> growth <strong>of</strong> gut mucosa <strong>and</strong>pancreas <strong>in</strong> neonatal rats. In this study, 7-d-old rats were<strong>in</strong>jected sc with BBS (20 g/kg) twice daily for 6 d. Gastricweight, fundic <strong>and</strong> antral mucosal height, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> density <strong>of</strong>parietal cells were <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong> BBS-treated pups comparedwith sal<strong>in</strong>e-treated controls.Demb<strong>in</strong>ski et al. (121, 122) demonstrated that BBS, adm<strong>in</strong>isteredto rats for 7 successive days, significantly <strong>in</strong>creased<strong>the</strong> weight <strong>and</strong> RNA <strong>and</strong> DNA contents <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> oxyntic mucosa<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> stomach <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> duodenal mucosa; somatostat<strong>in</strong>attenuated <strong>the</strong> proliferative effect <strong>of</strong> BBS. Antrectomy, whichremoves <strong>the</strong> gastr<strong>in</strong>-secret<strong>in</strong>g cells, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> CCK receptor<strong>in</strong>hibitor, L-364,718, partly reduced but did not abolish <strong>the</strong>proliferative effects <strong>of</strong> BSS, suggest<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> grow<strong>the</strong>nhanc<strong>in</strong>gmechanisms <strong>of</strong> BBS <strong>in</strong>volved gastr<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> CCKstimulation. More importantly, <strong>the</strong>se studies confirmed thatBBS had direct effects on <strong>the</strong> gastroduodenal mucosa.Later, Demb<strong>in</strong>ski et al. (122) extended <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>itial f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsby assess<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> BBS/GRP receptor antagonist,RC-3095, on BBS-mediated growth. BBS (10 g/kg) adm<strong>in</strong>isteredthree times daily for 2d<strong>in</strong>fasted rats significantly<strong>in</strong>creased <strong>the</strong> rate <strong>of</strong> DNA syn<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> gastroduodenalmucosa <strong>and</strong> pancreas as measured by <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>corporation <strong>of</strong>[ 3 H]thymid<strong>in</strong>e; this proliferative effect was abolished by RC-3095. These results provide fur<strong>the</strong>r evidence that BBS/GRPstimulates <strong>the</strong> growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> stomach <strong>and</strong> duodenum <strong>and</strong>that <strong>the</strong>se effects are due predom<strong>in</strong>antly to a direct effect <strong>of</strong>BBS/GRP stimulation.2. Small <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e. BBS also stimulates growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rema<strong>in</strong>der<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> small bowel mucosa. We exam<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> BBS<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevention <strong>of</strong> gut mucosal atrophy <strong>in</strong> Sprague-Dawleyrats given liquid ED (33). Four groups <strong>of</strong> rats were given anED <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>jected with sal<strong>in</strong>e (control), pentagastr<strong>in</strong> (250 g/kg), NT (300 g/kg), or BBS (10 g/kg) sc every 8 h. A fifthgroup was fed a regular chow diet. Atrophy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ilealmucosa was apparent on d 6 <strong>and</strong> 11, <strong>and</strong> atrophy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>jejunal mucosa was present by d 11. BBS prevented jejunalmucosal atrophy <strong>and</strong> significantly <strong>in</strong>creased ileal mucosalgrowth (mucosal weight, RNA, DNA, prote<strong>in</strong> content) comparedwith control.Chu et al. (123) determ<strong>in</strong>ed whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> trophic actions <strong>of</strong>BBS on <strong>the</strong> small bowel were mediated by nonlum<strong>in</strong>al orlum<strong>in</strong>al (i.e., pancreaticobiliary secretion) factors by construction<strong>of</strong> isolated small bowel loops [i.e., Thiry-Vella fistulas(TVFs)]. BBS <strong>in</strong>creased mucosal weight, DNA, <strong>and</strong> prote<strong>in</strong>content <strong>in</strong> both jejunal <strong>and</strong> ileal TVF compared withcontrol animals, suggest<strong>in</strong>g that BBS-mediated stimulation<strong>of</strong> small bowel mucosal growth is mediated by factors thatare <strong>in</strong>dependent <strong>of</strong> lum<strong>in</strong>al contents <strong>and</strong> pancreaticobiliarysecretion.In addition to its effects on gut mucosal growth, BBS exhibitsprotective effects <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> gut after <strong>in</strong>jury. Us<strong>in</strong>g a lethalenterocolitis model <strong>in</strong> rats <strong>in</strong>duced by <strong>the</strong> chemo<strong>the</strong>rapeuticagent methotrexate (MTX), BBS enhanced gut mucosalgrowth <strong>and</strong> significantly <strong>in</strong>hibited mortality <strong>in</strong> rats (124). Thebeneficial effect <strong>of</strong> BBS on survival was noted when BBS wasgiven before or at <strong>the</strong> same time as MTX, which suggestedthat BBS may act through additional mechanisms o<strong>the</strong>r thangut mucosal growth alone. One possibility is that BBS mayproduce its beneficial effects through enhancement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>immune system, which is a known action <strong>of</strong> BBS (125).3. Colon. Studies assess<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> BBS/GRP on <strong>the</strong>colonic mucosa are limited but, similar to <strong>the</strong> small bowel,appear to support a trophic effect <strong>of</strong> this agent <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> colon.Johnson <strong>and</strong> Guthrie (126) demonstrated that BBS (20 g/kg,three times daily for 7 d) stimulated colonic mucosal growth.Puccio <strong>and</strong> Lehy (119) found that adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> BBSorally <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> neonatal period stimulated colonic growth. Incontrast, we have not detected a proliferative effect <strong>of</strong> BBS <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> colon <strong>of</strong> chow-fed rats after 7 or 14 d (127). In rats givenan ED, BBS produced a proliferative effect only <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> proximalcolon. Therefore, although BBS appears to exert a trophiceffect on <strong>the</strong> colonic mucosa, <strong>the</strong> effects are less pronouncedthan <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> stomach or small bowel.4. Pancreas. A number <strong>of</strong> studies have shown that BBS stimulates<strong>the</strong> growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pancreas (97, 119, 120, 128). Forexample, Lehy <strong>and</strong> colleagues (119, 120) demonstrated atrophic response for BBS <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> pancreas as well as o<strong>the</strong>r GIDownloaded from edrv.endojournals.org by on July 16, 2007

Thomas et al. • <strong>Gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al</strong> <strong>Hormones</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Proliferation</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Reviews, October 2003, 24(5):571–599 579tissues. In addition, electron morphometric analysis <strong>in</strong>dicatedthat <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> pancreatic weight was due to hypertrophy<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ac<strong>in</strong>ar cells. Increases <strong>in</strong> pancreatic chymotryps<strong>in</strong><strong>and</strong> tryps<strong>in</strong>ogen content were noted, with little effecton lipase or colipase <strong>and</strong> amylase levels. Similar to its effectson <strong>the</strong> pancreatic ac<strong>in</strong>i, BBS stimulates endocr<strong>in</strong>e cells <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>pancreas (129).Liehr et al. (130) assessed <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong> CCK <strong>in</strong> BBS-<strong>in</strong>ducedgrowth <strong>in</strong> rats. Sprague-Dawley rats received sc <strong>in</strong>jections <strong>of</strong>BBS every 8 h for 5 d, alone or <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation with <strong>the</strong> CCKreceptor antagonist, L-364,718. BBS produced a dose-dependent<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> pancreatic weight, DNA <strong>and</strong> prote<strong>in</strong> content,as well as amylase <strong>and</strong> chymotryps<strong>in</strong>ogen levels. L-364,718significantly <strong>in</strong>hibited pancreatic growth <strong>in</strong>duced by a highconcentration (5 nmol/kg) <strong>of</strong> BBS but had m<strong>in</strong>imal effects ongrowth <strong>in</strong>duced by lower dosages <strong>of</strong> BBS. These results suggestthat low doses <strong>of</strong> BBS stimulate pancreatic growth <strong>in</strong> adirect manner, <strong>in</strong>dependent <strong>of</strong> CCK, whereas high doses <strong>of</strong>BBS act <strong>in</strong> part through CCK release.More recently, Fiorucci et al. (131) found that chronic BBSadm<strong>in</strong>istration stimulated pancreatic regeneration after pancreatectomy<strong>in</strong> pigs. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, <strong>the</strong>se studies exam<strong>in</strong>ed<strong>the</strong> cellular processes that may be regulated by BBS. Threegroups <strong>of</strong> pigs underwent sham operation, subtotal distalpancreatectomy, or subtotal pancreatectomy comb<strong>in</strong>ed withBBS for 4 wk. After treatment, <strong>the</strong> pancreas was removed,weighed, <strong>and</strong> assayed for p42 <strong>and</strong> p44 MAPK, p46 Shc ,p52 Shc , p66 Shc , <strong>and</strong> Grb2. BBS adm<strong>in</strong>istration resulted <strong>in</strong> a100% <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> residual pancreatic tissue when comparedwith control animals <strong>and</strong> approximately a 3-fold <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> rate <strong>of</strong> pancreatic ac<strong>in</strong>ar cell proliferation. Also, BBSadm<strong>in</strong>istration significantly <strong>in</strong>creased p46 Shc /p52 Shc <strong>and</strong>MAPK expression <strong>and</strong>/or activity <strong>in</strong> whole pancreas extracts.These results fur<strong>the</strong>r demonstrate a proliferative effect<strong>of</strong> BBS <strong>in</strong> a large animal model <strong>and</strong> provide evidence that BBScan stimulate cell proliferation via <strong>the</strong> MAPK pathway.Upp et al. (128) demonstrated that BBS had both direct <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>direct actions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> pancreas. Polyam<strong>in</strong>e syn<strong>the</strong>sis, anessential part <strong>of</strong> DNA syn<strong>the</strong>sis, was assessed with BBS adm<strong>in</strong>istrationover a time course. BBS produced significantpancreatic hyperplasia (<strong>in</strong>creased pancreatic weight, prote<strong>in</strong>,<strong>and</strong> DNA content) after 14 d <strong>of</strong> treatment. CR1409, <strong>the</strong> CCKreceptor antagonist, <strong>in</strong>hibited only BBS-mediated <strong>in</strong>creases<strong>in</strong> DNA content. BBS stimulated polyam<strong>in</strong>e biosyn<strong>the</strong>sis asearly as 2 h after adm<strong>in</strong>istration; CR1409 did not <strong>in</strong>hibit this<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> polyam<strong>in</strong>es. These results suggested that <strong>the</strong> trophicactions <strong>of</strong> BBS are both direct <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>direct <strong>and</strong> that <strong>the</strong>direct effects are mediated by polyam<strong>in</strong>e syn<strong>the</strong>sis.D. NTThe physiological functions <strong>of</strong> NT <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> GI tract <strong>in</strong>cludestimulation <strong>of</strong> pancreatic <strong>and</strong> biliary secretions (37) <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>hibition<strong>of</strong> small bowel <strong>and</strong> gastric motility (38). In addition,NT stimulates growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gastric antrum, small bowel (33,34, 42), colon (132), <strong>and</strong> pancreas (40, 133).1. Stomach. Feurle et al. (40) demonstrated that sc adm<strong>in</strong>istration<strong>of</strong> high dosages <strong>of</strong> NT for 2 wk <strong>in</strong>creased prote<strong>in</strong>concentration <strong>and</strong> thickness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gastric antrum <strong>in</strong> Wistarrats, whereas DNA content <strong>and</strong> weight were not affected. Incontrast, Hoang et al. (134) noted that NT alone had no effecton <strong>the</strong> oxyntic gl<strong>and</strong> area or <strong>the</strong> antrum, but it <strong>in</strong>hibited<strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> antral weight, DNA, <strong>and</strong> prote<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>duced bysecret<strong>in</strong>. The effects <strong>of</strong> NT on antral growth are, <strong>the</strong>refore,m<strong>in</strong>imal at best <strong>and</strong> may occur with prolonged, high dosages<strong>of</strong> NT.2. Small bowel. In contrast to <strong>the</strong> stomach, <strong>the</strong> trophic effects<strong>of</strong> NT <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> small bowel are more pronounced. Wood et al.(42) first noted that NT stimulated <strong>the</strong> small bowel mucosa<strong>of</strong> rats fed a normal chow diet. We have shown that adm<strong>in</strong>istration<strong>of</strong> NT prevents gut mucosal atrophy <strong>in</strong>duced byfeed<strong>in</strong>g rats an ED (Fig. 4) (Ref. 34) <strong>and</strong> stimulates mucosalgrowth <strong>in</strong> defunctionalized self-empty<strong>in</strong>g jejunoileal loopsor isolated TVFs, thus support<strong>in</strong>g a direct role for NT <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>stimulation <strong>of</strong> gut mucosal growth. These f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs demonstratethat NT is an important trophic hormone that canma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> even augment gut mucosal structure by an<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> overall mucosal cellularity. Consistent with ourf<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs, Vagianos et al. (135) reported that NT restores gutFIG. 4. NT prevents small bowel mucosal atrophy associatedwith ED. Histology <strong>of</strong> Sprague-Dawley ratsmall bowel after ED, ED <strong>and</strong> NT (<strong>in</strong>jected sc 300 g/kgthree times a day), <strong>and</strong> chow (control) for 5 d.Downloaded from edrv.endojournals.org by on July 16, 2007