Automating Manufacturing Systems - Process Control and ...

Automating Manufacturing Systems - Process Control and ...

Automating Manufacturing Systems - Process Control and ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

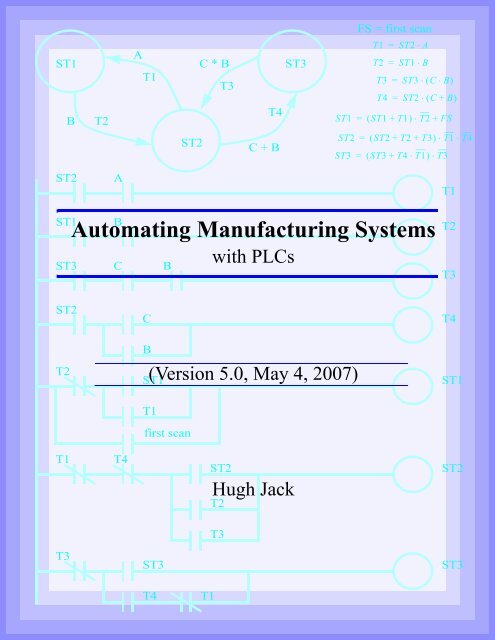

ST1<br />

B<br />

T2<br />

A<br />

T1<br />

C * B<br />

T3<br />

page 0<br />

ST3<br />

T4<br />

FS = first scan<br />

T1<br />

T2<br />

=<br />

=<br />

ST2 ⋅ A<br />

ST1 ⋅ B<br />

T3 = ST3 ⋅ ( C ⋅ B)<br />

T4 = ST2 ⋅ ( C+<br />

B)<br />

ST1 = ( ST1 + T1) ⋅ T2 + FS<br />

ST2<br />

C + B<br />

ST2 = ( ST2 + T2 + T3) ⋅T1 ⋅T4<br />

ST3 = ( ST3 + T4 ⋅ T1) ⋅ T3<br />

ST2<br />

A<br />

T1<br />

ST1 B<br />

<strong>Automating</strong> <strong>Manufacturing</strong> <strong>Systems</strong><br />

ST3 C B<br />

with PLCs<br />

T2<br />

T3<br />

ST2<br />

C<br />

T4<br />

B<br />

T2<br />

(Version 5.0, May 4, 2007)<br />

ST1<br />

ST1<br />

T1<br />

first scan<br />

T1<br />

T4<br />

ST2<br />

Hugh Jack<br />

T2<br />

ST2<br />

T3<br />

T3<br />

ST3<br />

ST3<br />

T4<br />

T1

page 0<br />

Copyright (c) 1993-2007 Hugh Jack (jackh@gvsu.edu).<br />

Permission is granted to copy, distribute <strong>and</strong>/or modify this document under the<br />

terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version<br />

published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no<br />

Front-Cover Texts, <strong>and</strong> no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included<br />

in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License".<br />

This document is provided as-is with no warranty, implied or otherwise. There<br />

have been attempts to eliminate errors from this document, but there is no doubt<br />

that errors remain. As a result, the author does not assume any responsibility for<br />

errors <strong>and</strong> omissions, or damages resulting from the use of the information provided.<br />

Additional materials <strong>and</strong> updates for this work will be available at http://claymore.engineer.gvsu.edu/~jackh/books.html<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

page i<br />

1.1 TODO LIST 1.3<br />

2. PROGRAMMABLE LOGIC CONTROLLERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2.1<br />

2.1 INTRODUCTION 2.1<br />

2.1.1 Ladder Logic 2.1<br />

2.1.2 Programming 2.6<br />

2.1.3 PLC Connections 2.10<br />

2.1.4 Ladder Logic Inputs 2.11<br />

2.1.5 Ladder Logic Outputs 2.12<br />

2.2 A CASE STUDY 2.13<br />

2.3 SUMMARY 2.14<br />

2.4 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 2.15<br />

2.5 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 2.15<br />

2.6 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 2.16<br />

3. PLC HARDWARE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.1<br />

3.1 INTRODUCTION 3.1<br />

3.2 INPUTS AND OUTPUTS 3.2<br />

3.2.1 Inputs 3.3<br />

3.2.2 Output Modules 3.7<br />

3.3 RELAYS 3.13<br />

3.4 A CASE STUDY 3.14<br />

3.5 ELECTRICAL WIRING DIAGRAMS 3.15<br />

3.5.1 JIC Wiring Symbols 3.18<br />

3.6 SUMMARY 3.22<br />

3.7 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 3.22<br />

3.8 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 3.25<br />

3.9 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 3.28<br />

4. LOGICAL SENSORS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.1<br />

4.1 INTRODUCTION 4.1<br />

4.2 SENSOR WIRING 4.1<br />

4.2.1 Switches 4.2<br />

4.2.2 Transistor Transistor Logic (TTL) 4.3<br />

4.2.3 Sinking/Sourcing 4.3<br />

4.2.4 Solid State Relays 4.10<br />

4.3 PRESENCE DETECTION 4.11<br />

4.3.1 Contact Switches 4.11<br />

4.3.2 Reed Switches 4.11<br />

4.3.3 Optical (Photoelectric) Sensors 4.12<br />

4.3.4 Capacitive Sensors 4.19<br />

4.3.5 Inductive Sensors 4.23<br />

4.3.6 Ultrasonic 4.25<br />

4.3.7 Hall Effect 4.25<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

page ii<br />

4.3.8 Fluid Flow 4.26<br />

4.4 SUMMARY 4.26<br />

4.5 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 4.27<br />

4.6 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 4.30<br />

4.7 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 4.36<br />

5. LOGICAL ACTUATORS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5.1<br />

5.1 INTRODUCTION 5.1<br />

5.2 SOLENOIDS 5.1<br />

5.3 VALVES 5.2<br />

5.4 CYLINDERS 5.4<br />

5.5 HYDRAULICS 5.6<br />

5.6 PNEUMATICS 5.8<br />

5.7 MOTORS 5.9<br />

5.8 OTHERS 5.10<br />

5.9 SUMMARY 5.10<br />

5.10 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 5.10<br />

5.11 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 5.11<br />

5.12 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 5.12<br />

6. BOOLEAN LOGIC DESIGN . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6.1<br />

6.1 INTRODUCTION 6.1<br />

6.2 BOOLEAN ALGEBRA 6.1<br />

6.3 LOGIC DESIGN 6.6<br />

6.3.1 Boolean Algebra Techniques 6.13<br />

6.4 COMMON LOGIC FORMS 6.14<br />

6.4.1 Complex Gate Forms 6.14<br />

6.4.2 Multiplexers 6.15<br />

6.5 SIMPLE DESIGN CASES 6.17<br />

6.5.1 Basic Logic Functions 6.17<br />

6.5.2 Car Safety System 6.18<br />

6.5.3 Motor Forward/Reverse 6.18<br />

6.5.4 A Burglar Alarm 6.19<br />

6.6 SUMMARY 6.23<br />

6.7 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 6.24<br />

6.8 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 6.27<br />

6.9 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 6.37<br />

7. KARNAUGH MAPS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7.1<br />

7.1 INTRODUCTION 7.1<br />

7.2 SUMMARY 7.4<br />

7.3 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 7.5<br />

7.4 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 7.11<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

page iii<br />

7.5 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 7.17<br />

8. PLC OPERATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8.1<br />

8.1 INTRODUCTION 8.1<br />

8.2 OPERATION SEQUENCE 8.3<br />

8.2.1 The Input <strong>and</strong> Output Scans 8.4<br />

8.2.2 The Logic Scan 8.4<br />

8.3 PLC STATUS 8.6<br />

8.4 MEMORY TYPES 8.6<br />

8.5 SOFTWARE BASED PLCS 8.7<br />

8.6 SUMMARY 8.7<br />

8.7 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 8.8<br />

8.8 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 8.8<br />

8.9 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 8.9<br />

9. LATCHES, TIMERS, COUNTERS AND MORE . . . . . . . . . . . . 9.1<br />

9.1 INTRODUCTION 9.1<br />

9.2 LATCHES 9.2<br />

9.3 TIMERS 9.6<br />

9.4 COUNTERS 9.14<br />

9.5 MASTER CONTROL RELAYS (MCRs) 9.17<br />

9.6 INTERNAL BITS 9.19<br />

9.7 DESIGN CASES 9.20<br />

9.7.1 Basic Counters And Timers 9.20<br />

9.7.2 More Timers And Counters 9.21<br />

9.7.3 Deadman Switch 9.22<br />

9.7.4 Conveyor 9.23<br />

9.7.5 Accept/Reject Sorting 9.24<br />

9.7.6 Shear Press 9.26<br />

9.8 SUMMARY 9.27<br />

9.9 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 9.28<br />

9.10 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 9.32<br />

9.11 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 9.43<br />

10. STRUCTURED LOGIC DESIGN . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.1<br />

10.1 INTRODUCTION 10.1<br />

10.2 PROCESS SEQUENCE BITS 10.2<br />

10.3 TIMING DIAGRAMS 10.6<br />

10.4 DESIGN CASES 10.9<br />

10.5 SUMMARY 10.9<br />

10.6 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 10.9<br />

10.7 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 10.10<br />

10.8 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 10.14<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

page iv<br />

13.11<br />

11. FLOWCHART BASED DESIGN . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11.1<br />

11.1 INTRODUCTION 11.1<br />

11.2 BLOCK LOGIC 11.4<br />

11.3 SEQUENCE BITS 11.11<br />

11.4 SUMMARY 11.15<br />

11.5 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 11.15<br />

11.6 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 11.16<br />

11.7 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 11.26<br />

12. STATE BASED DESIGN . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12.1<br />

12.1 INTRODUCTION 12.1<br />

12.1.1 State Diagram Example 12.4<br />

12.1.2 Conversion to Ladder Logic 12.7<br />

Block Logic Conversion 12.7<br />

State Equations 12.16<br />

State-Transition Equations 12.24<br />

12.2 SUMMARY 12.29<br />

12.3 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 12.29<br />

12.4 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 12.34<br />

12.5 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 12.49<br />

13. NUMBERS AND DATA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13.1<br />

13.1 INTRODUCTION 13.1<br />

13.2 NUMERICAL VALUES 13.2<br />

13.2.1 Binary 13.2<br />

Boolean Operations 13.5<br />

Binary Mathematics 13.6<br />

13.2.2 Other Base Number <strong>Systems</strong> 13.10<br />

13.2.3 BCD (Binary Coded Decimal) 13.11<br />

13.3 DATA CHARACTERIZATION 13.11<br />

13.3.1 ASCII (American St<strong>and</strong>ard Code for Information Interchange)<br />

13.3.2 Parity 13.14<br />

13.3.3 Checksums 13.15<br />

13.3.4 Gray Code 13.16<br />

13.4 SUMMARY 13.17<br />

13.5 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 13.17<br />

13.6 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 13.20<br />

13.7 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 13.23<br />

14. PLC MEMORY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14.1<br />

14.1 INTRODUCTION 14.1<br />

14.2 PROGRAM VS VARIABLE MEMORY 14.1<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

page v<br />

14.3 PROGRAMS 14.3<br />

14.4 VARIABLES (TAGS) 14.3<br />

14.4.1 Timer <strong>and</strong> Counter Memory 14.6<br />

14.4.2 PLC Status Bits 14.8<br />

14.4.3 User Function <strong>Control</strong> Memory 14.11<br />

14.5 SUMMARY 14.12<br />

14.6 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 14.12<br />

14.7 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 14.13<br />

14.8 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 14.15<br />

15. LADDER LOGIC FUNCTIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15.1<br />

15.1 INTRODUCTION 15.1<br />

15.2 DATA HANDLING 15.3<br />

15.2.1 Move Functions 15.3<br />

15.2.2 Mathematical Functions 15.5<br />

15.2.3 Conversions 15.10<br />

15.2.4 Array Data Functions 15.11<br />

Statistics 15.12<br />

Block Operations 15.13<br />

15.3 LOGICAL FUNCTIONS 15.15<br />

15.3.1 Comparison of Values 15.15<br />

15.3.2 Boolean Functions 15.21<br />

15.4 DESIGN CASES 15.22<br />

15.4.1 Simple Calculation 15.22<br />

15.4.2 For-Next 15.23<br />

15.4.3 Series Calculation 15.24<br />

15.4.4 Flashing Lights 15.25<br />

15.5 SUMMARY 15.25<br />

15.6 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 15.26<br />

15.7 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 15.28<br />

15.8 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 15.34<br />

16. ADVANCED LADDER LOGIC FUNCTIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.1<br />

16.1 INTRODUCTION 16.1<br />

16.2 LIST FUNCTIONS 16.1<br />

16.2.1 Shift Registers 16.1<br />

16.2.2 Stacks 16.3<br />

16.2.3 Sequencers 16.6<br />

16.3 PROGRAM CONTROL 16.9<br />

16.3.1 Branching <strong>and</strong> Looping 16.9<br />

16.3.2 Fault H<strong>and</strong>ling 16.14<br />

16.3.3 Interrupts 16.15<br />

16.4 INPUT AND OUTPUT FUNCTIONS 16.17<br />

16.4.1 Immediate I/O Instructions 16.17<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

page vi<br />

16.5 DESIGN TECHNIQUES 16.19<br />

16.5.1 State Diagrams 16.19<br />

16.6 DESIGN CASES 16.24<br />

16.6.1 If-Then 16.24<br />

16.6.2 Traffic Light 16.25<br />

16.7 SUMMARY 16.25<br />

16.8 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 16.26<br />

16.9 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 16.28<br />

16.10 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 16.37<br />

17. OPEN CONTROLLERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17.1<br />

17.1 INTRODUCTION 17.1<br />

17.2 IEC 61131 17.2<br />

17.3 OPEN ARCHITECTURE CONTROLLERS 17.3<br />

17.4 SUMMARY 17.4<br />

17.5 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 17.4<br />

17.6 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 17.4<br />

17.7 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 17.4<br />

18. INSTRUCTION LIST PROGRAMMING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18.1<br />

18.1 INTRODUCTION 18.1<br />

18.2 THE IEC 61131 VERSION 18.1<br />

18.3 THE ALLEN-BRADLEY VERSION 18.4<br />

18.4 SUMMARY 18.9<br />

18.5 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 18.10<br />

18.6 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 18.10<br />

18.7 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 18.10<br />

19. STRUCTURED TEXT PROGRAMMING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19.1<br />

19.1 INTRODUCTION 19.1<br />

19.2 THE LANGUAGE 19.2<br />

19.2.1 Elements of the Language 19.3<br />

19.2.2 Putting Things Together in a Program 19.9<br />

19.3 AN EXAMPLE 19.14<br />

19.4 SUMMARY 19.16<br />

19.5 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 19.16<br />

19.6 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 19.16<br />

19.7 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 19.16<br />

20. SEQUENTIAL FUNCTION CHARTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20.1<br />

20.1 INTRODUCTION 20.1<br />

20.2 A COMPARISON OF METHODS 20.16<br />

20.3 SUMMARY 20.16<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

page vii<br />

20.4 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 20.17<br />

20.5 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 20.18<br />

20.6 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 20.25<br />

21. FUNCTION BLOCK PROGRAMMING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21.1<br />

21.1 INTRODUCTION 21.1<br />

21.2 CREATING FUNCTION BLOCKS 21.3<br />

21.3 DESIGN CASE 21.4<br />

21.4 SUMMARY 21.4<br />

21.5 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 21.5<br />

21.6 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 21.5<br />

21.7 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 21.5<br />

22. ANALOG INPUTS AND OUTPUTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22.1<br />

22.1 INTRODUCTION 22.1<br />

22.2 ANALOG INPUTS 22.2<br />

22.2.1 Analog Inputs With a PLC-5 22.9<br />

22.3 ANALOG OUTPUTS 22.13<br />

22.3.1 Analog Outputs With A PLC-5 22.16<br />

22.3.2 Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) Outputs 22.18<br />

22.3.3 Shielding 22.20<br />

22.4 DESIGN CASES 22.22<br />

22.4.1 <strong>Process</strong> Monitor 22.22<br />

22.5 SUMMARY 22.22<br />

22.6 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 22.23<br />

22.7 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 22.24<br />

22.8 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 22.29<br />

23. CONTINUOUS SENSORS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23.1<br />

23.1 INTRODUCTION 23.1<br />

23.2 INDUSTRIAL SENSORS 23.2<br />

23.2.1 Angular Displacement 23.3<br />

Potentiometers 23.3<br />

23.2.2 Encoders 23.4<br />

Tachometers 23.8<br />

23.2.3 Linear Position 23.8<br />

Potentiometers 23.8<br />

Linear Variable Differential Transformers (LVDT)23.9<br />

Moire Fringes 23.11<br />

Accelerometers 23.12<br />

23.2.4 Forces <strong>and</strong> Moments 23.15<br />

Strain Gages 23.15<br />

Piezoelectric 23.18<br />

23.2.5 Liquids <strong>and</strong> Gases 23.20<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

page viii<br />

Pressure 23.21<br />

Venturi Valves 23.22<br />

Coriolis Flow Meter 23.23<br />

Magnetic Flow Meter 23.24<br />

Ultrasonic Flow Meter 23.24<br />

Vortex Flow Meter 23.24<br />

Positive Displacement Meters 23.25<br />

Pitot Tubes 23.25<br />

23.2.6 Temperature 23.25<br />

Resistive Temperature Detectors (RTDs) 23.26<br />

Thermocouples 23.26<br />

Thermistors 23.28<br />

Other Sensors 23.30<br />

23.2.7 Light 23.30<br />

Light Dependant Resistors (LDR) 23.30<br />

23.2.8 Chemical 23.31<br />

pH 23.31<br />

Conductivity 23.31<br />

23.2.9 Others 23.32<br />

23.3 INPUT ISSUES 23.32<br />

23.4 SENSOR GLOSSARY 23.35<br />

23.5 SUMMARY 23.36<br />

23.6 REFERENCES 23.37<br />

23.7 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 23.37<br />

23.8 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 23.38<br />

23.9 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 23.40<br />

24. CONTINUOUS ACTUATORS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24.1<br />

24.1 INTRODUCTION 24.1<br />

24.2 ELECTRIC MOTORS 24.1<br />

24.2.1 Basic Brushed DC Motors 24.3<br />

24.2.2 AC Motors 24.7<br />

24.2.3 Brushless DC Motors 24.15<br />

24.2.4 Stepper Motors 24.17<br />

24.2.5 Wound Field Motors 24.19<br />

24.3 HYDRAULICS 24.23<br />

24.4 OTHER SYSTEMS 24.24<br />

24.5 SUMMARY 24.25<br />

24.6 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 24.25<br />

24.7 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 24.26<br />

24.8 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 24.27<br />

25. CONTINUOUS CONTROL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25.1<br />

25.1 INTRODUCTION 25.1<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

page ix<br />

25.2 CONTROL OF LOGICAL ACTUATOR SYSTEMS 25.4<br />

25.3 CONTROL OF CONTINUOUS ACTUATOR SYSTEMS 25.5<br />

25.3.1 Block Diagrams 25.5<br />

25.3.2 Feedback <strong>Control</strong> <strong>Systems</strong> 25.6<br />

25.3.3 Proportional <strong>Control</strong>lers 25.8<br />

25.3.4 PID <strong>Control</strong> <strong>Systems</strong> 25.12<br />

25.4 DESIGN CASES 25.14<br />

25.4.1 Oven Temperature <strong>Control</strong> 25.14<br />

25.4.2 Water Tank Level <strong>Control</strong> 25.17<br />

25.4.3 Position Measurement 25.20<br />

25.5 SUMMARY 25.20<br />

25.6 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 25.21<br />

25.7 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 25.22<br />

25.8 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 25.26<br />

26. FUZZY LOGIC . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26.1<br />

26.1 INTRODUCTION 26.1<br />

26.2 COMMERCIAL CONTROLLERS 26.7<br />

26.3 REFERENCES 26.7<br />

26.4 SUMMARY 26.7<br />

26.5 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 26.8<br />

26.6 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 26.8<br />

26.7 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 26.8<br />

27. SERIAL COMMUNICATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27.1<br />

27.1 INTRODUCTION 27.1<br />

27.2 SERIAL COMMUNICATIONS 27.2<br />

27.2.1 RS-232 27.5<br />

ASCII Functions 27.9<br />

27.3 PARALLEL COMMUNICATIONS 27.13<br />

27.4 DESIGN CASES 27.14<br />

27.4.1 PLC Interface To a Robot 27.14<br />

27.5 SUMMARY 27.15<br />

27.6 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 27.15<br />

27.7 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 27.16<br />

27.8 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 27.18<br />

28. NETWORKING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28.1<br />

28.1 INTRODUCTION 28.1<br />

28.1.1 Topology 28.2<br />

28.1.2 OSI Network Model 28.3<br />

28.1.3 Networking Hardware 28.5<br />

28.1.4 <strong>Control</strong> Network Issues 28.7<br />

28.2 NETWORK STANDARDS 28.8<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

page x<br />

28.2.1 Devicenet 28.8<br />

28.2.2 CANbus 28.12<br />

28.2.3 <strong>Control</strong>net 28.13<br />

28.2.4 Ethernet 28.14<br />

28.2.5 Profibus 28.15<br />

28.2.6 Sercos 28.15<br />

28.3 PROPRIETARY NETWORKS 28.16<br />

28.3.1 Data Highway 28.16<br />

28.4 NETWORK COMPARISONS 28.20<br />

28.5 DESIGN CASES 28.22<br />

28.5.1 Devicenet 28.22<br />

28.6 SUMMARY 28.23<br />

28.7 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 28.23<br />

28.8 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 28.24<br />

28.9 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 28.28<br />

29. INTERNET . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29.1<br />

29.1 INTRODUCTION 29.1<br />

29.1.1 Computer Addresses 29.2<br />

IPV6 29.3<br />

29.1.2 Phone Lines 29.3<br />

29.1.3 Mail Transfer Protocols 29.3<br />

29.1.4 FTP - File Transfer Protocol 29.4<br />

29.1.5 HTTP - Hypertext Transfer Protocol 29.4<br />

29.1.6 Novell 29.4<br />

29.1.7 Security 29.5<br />

Firewall 29.5<br />

IP Masquerading 29.5<br />

29.1.8 HTML - Hyper Text Markup Language 29.5<br />

29.1.9 URLs 29.6<br />

29.1.10 Encryption 29.6<br />

29.1.11 Compression 29.7<br />

29.1.12 Clients <strong>and</strong> Servers 29.7<br />

29.1.13 Java 29.9<br />

29.1.14 Javascript 29.9<br />

29.1.15 CGI 29.9<br />

29.1.16 ActiveX 29.9<br />

29.1.17 Graphics 29.10<br />

29.2 DESIGN CASES 29.10<br />

29.2.1 Remote Monitoring System 29.10<br />

29.3 SUMMARY 29.11<br />

29.4 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 29.11<br />

29.5 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 29.11<br />

29.6 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 29.11<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

page xi<br />

30. HUMAN MACHINE INTERFACES (HMI) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30.1<br />

30.1 INTRODUCTION 30.1<br />

30.2 HMI/MMI DESIGN 30.2<br />

30.3 DESIGN CASES 30.3<br />

30.4 SUMMARY 30.3<br />

30.5 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 30.4<br />

30.6 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 30.4<br />

30.7 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 30.4<br />

31. ELECTRICAL DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION . . . . . . . . . . 31.1<br />

31.1 INTRODUCTION 31.1<br />

31.2 ELECTRICAL WIRING DIAGRAMS 31.1<br />

31.2.1 Selecting Voltages 31.8<br />

31.2.2 Grounding 31.9<br />

31.2.3 Wiring 31.12<br />

31.2.4 Suppressors 31.13<br />

31.2.5 PLC Enclosures 31.14<br />

31.2.6 Wire <strong>and</strong> Cable Grouping 31.16<br />

31.3 FAIL-SAFE DESIGN 31.17<br />

31.4 SAFETY RULES SUMMARY 31.18<br />

31.5 REFERENCES 31.20<br />

31.6 SUMMARY 31.20<br />

31.7 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 31.20<br />

31.8 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 31.20<br />

31.9 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 31.20<br />

32. SOFTWARE ENGINEERING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32.1<br />

32.1 INTRODUCTION 32.1<br />

32.1.1 Fail Safe Design 32.1<br />

32.2 DEBUGGING 32.2<br />

32.2.1 Troubleshooting 32.3<br />

32.2.2 Forcing 32.3<br />

32.3 PROCESS MODELLING 32.3<br />

32.4 PROGRAMMING FOR LARGE SYSTEMS 32.8<br />

32.4.1 Developing a Program Structure 32.8<br />

32.4.2 Program Verification <strong>and</strong> Simulation 32.11<br />

32.5 DOCUMENTATION 32.12<br />

32.6 COMMISIONING 32.20<br />

32.7 SAFETY 32.20<br />

32.7.1 IEC 61508/61511 safety st<strong>and</strong>ards 32.21<br />

32.8 LEAN MANUFACTURING 32.22<br />

32.9 REFERENCES 32.23<br />

32.10 SUMMARY 32.23<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

page xii<br />

32.11 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 32.23<br />

32.12 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 32.23<br />

32.13 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 32.23<br />

33. SELECTING A PLC . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33.1<br />

33.1 INTRODUCTION 33.1<br />

33.2 SPECIAL I/O MODULES 33.6<br />

33.3 SUMMARY 33.9<br />

33.4 PRACTICE PROBLEMS 33.10<br />

33.5 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS 33.10<br />

33.6 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS 33.10<br />

34. FUNCTION REFERENCE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34.1<br />

34.1 FUNCTION DESCRIPTIONS 34.1<br />

34.1.1 General Functions 34.1<br />

34.1.2 Program <strong>Control</strong> 34.3<br />

34.1.3 Timers <strong>and</strong> Counters 34.5<br />

34.1.4 Compare 34.10<br />

34.1.5 Calculation <strong>and</strong> Conversion 34.14<br />

34.1.6 Logical 34.20<br />

34.1.7 Move 34.21<br />

34.1.8 File 34.22<br />

34.1.9 List 34.27<br />

34.1.10 Program <strong>Control</strong> 34.30<br />

34.1.11 Advanced Input/Output 34.34<br />

34.1.12 String 34.37<br />

34.2 DATA TYPES 34.42<br />

35. COMBINED GLOSSARY OF TERMS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35.1<br />

35.1 A 35.1<br />

35.2 B 35.2<br />

35.3 C 35.5<br />

35.4 D 35.9<br />

35.5 E 35.11<br />

35.6 F 35.12<br />

35.7 G 35.13<br />

35.8 H 35.14<br />

35.9 I 35.14<br />

35.10 J 35.16<br />

35.11 K 35.16<br />

35.12 L 35.17<br />

35.13 M 35.17<br />

35.14 N 35.19<br />

35.15 O 35.20<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

page xiii<br />

35.16 P 35.21<br />

35.17 Q 35.23<br />

35.18 R 35.23<br />

35.19 S 35.25<br />

35.20 T 35.27<br />

35.21 U 35.28<br />

35.22 V 35.29<br />

35.23 W 35.29<br />

35.24 X 35.30<br />

35.25 Y 35.30<br />

35.26 Z 35.30<br />

36. PLC REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36.1<br />

36.1 SUPPLIERS 36.1<br />

36.2 PROFESSIONAL INTEREST GROUPS 36.2<br />

36.3 PLC/DISCRETE CONTROL REFERENCES 36.2<br />

37. GNU Free Documentation License . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37.1<br />

37.1 PREAMBLE 37.1<br />

37.2 APPLICABILITY AND DEFINITIONS 37.1<br />

37.3 VERBATIM COPYING 37.2<br />

37.4 COPYING IN QUANTITY 37.3<br />

37.5 MODIFICATIONS 37.3<br />

37.6 COMBINING DOCUMENTS 37.5<br />

37.7 COLLECTIONS OF DOCUMENTS 37.5<br />

37.8 AGGREGATION WITH INDEPENDENT WORKS 37.6<br />

37.9 TRANSLATION 37.6<br />

37.10 TERMINATION 37.6<br />

37.11 FUTURE REVISIONS OF THIS LICENSE 37.6<br />

37.12 How to use this License for your documents 37.7<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 1.1<br />

PREFACE<br />

Designing software for control systems is difficult. Experienced controls engineers<br />

have learned many techniques that allow them to solve problems. This book was written to<br />

present methods for designing controls software using Programmable Logic <strong>Control</strong>lers<br />

(PLCs). It is my personal hope that by employing the knowledge in the book that you will<br />

be able to quickly write controls programs that work as expected (<strong>and</strong> avoid having to<br />

learn by costly mistakes.)<br />

This book has been designed for students with some knowledge of technology,<br />

including limited electricity, who wish to learn the discipline of practical control system<br />

design on commonly used hardware. To this end the book will use the Allen Bradley <strong>Control</strong>Logix<br />

processors to allow depth. Although the chapters will focus on specific hardware,<br />

the techniques are portable to other PLCs. Whenever possible the IEC 61131<br />

programming st<strong>and</strong>ards will be used to help in the use of other PLCs.<br />

In some cases the material will build upon the content found in a linear controls<br />

course. But, a heavy emphasis is placed on discrete control systems. Figure 1.1 crudely<br />

shows some of the basic categories of control system problems.<br />

CONTROL<br />

CONTINUOUS<br />

DISCRETE<br />

LINEAR NON_LINEAR CONDITIONAL SEQUENTIAL<br />

EVENT BASED<br />

e.g. MRAC<br />

TEMPORAL<br />

e.g. PID<br />

BOOLEAN<br />

e.g. FUZZY LOGIC<br />

e.g. COUNTERS<br />

EXPERT SYSTEMS e.g. TIMERS<br />

Figure 1.1<br />

<strong>Control</strong> Dichotomy<br />

• Continuous - The values to be controlled change smoothly. e.g. the speed of a car.<br />

• Logical/Discrete - The value to be controlled are easily described as on-off. e.g.<br />

the car motor is on-off. NOTE: all systems are continuous but they can be<br />

treated as logical for simplicity.<br />

e.g. “When I do this, that always happens!” For example, when the power<br />

is turned on, the press closes!<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 1.2<br />

• Linear - Can be described with a simple differential equation. This is the preferred<br />

starting point for simplicity, <strong>and</strong> a common approximation for real world<br />

problems.<br />

e.g. A car can be driving around a track <strong>and</strong> can pass same the same spot at<br />

a constant velocity. But, the longer the car runs, the mass decreases, <strong>and</strong><br />

it travels faster, but requires less gas, etc. Basically, the math gets<br />

tougher, <strong>and</strong> the problem becomes non-linear.<br />

e.g. We are driving the perfect car with no friction, with no drag, <strong>and</strong> can<br />

predict how it will work perfectly.<br />

• Non-Linear - Not Linear. This is how the world works <strong>and</strong> the mathematics<br />

become much more complex.<br />

e.g. As rocket approaches sun, gravity increases, so control must change.<br />

• Sequential - A logical controller that will keep track of time <strong>and</strong> previous events.<br />

The difference between these control systems can be emphasized by considering a<br />

simple elevator. An elevator is a car that travels between floors, stopping at precise<br />

heights. There are certain logical constraints used for safety <strong>and</strong> convenience. The points<br />

below emphasize different types of control problems in the elevator.<br />

Logical:<br />

1. The elevator must move towards a floor when a button is pushed.<br />

2. The elevator must open a door when it is at a floor.<br />

3. It must have the door closed before it moves.<br />

etc.<br />

Linear:<br />

1. If the desired position changes to a new value, accelerate quickly<br />

towards the new position.<br />

2. As the elevator approaches the correct position, slow down.<br />

Non-linear:<br />

1 Accelerate slowly to start.<br />

2. Decelerate as you approach the final position.<br />

3. Allow faster motion while moving.<br />

4. Compensate for cable stretch, <strong>and</strong> changing spring constant, etc.<br />

Logical <strong>and</strong> sequential control is preferred for system design. These systems are<br />

more stable, <strong>and</strong> often lower cost. Most continuous systems can be controlled logically.<br />

But, some times we will encounter a system that must be controlled continuously. When<br />

this occurs the control system design becomes more dem<strong>and</strong>ing. When improperly controlled,<br />

continuous systems may be unstable <strong>and</strong> become dangerous.<br />

When a system is well behaved we say it is self regulating. These systems don’t<br />

need to be closely monitored, <strong>and</strong> we use open loop control. An open loop controller will<br />

set a desired position for a system, but no sensors are used to verify the position. When a<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 1.3<br />

system must be constantly monitored <strong>and</strong> the control output adjusted we say it is closed<br />

loop. A cruise control in a car is an excellent example. This will monitor the actual speed<br />

of a car, <strong>and</strong> adjust the speed to meet a set target speed.<br />

Many control technologies are available for control. Early control systems relied<br />

upon mechanisms <strong>and</strong> electronics to build controlled. Most modern controllers use a computer<br />

to achieve control. The most flexible of these controllers is the PLC (Programmable<br />

Logic <strong>Control</strong>ler).<br />

The book has been set up to aid the reader, as outlined below.<br />

Sections labeled Aside: are for topics that would be of interest to one discipline,<br />

such as electrical or mechanical.<br />

Sections labeled Note: are for clarification, to provide hints, or to add<br />

explanation.<br />

Each chapter supports about 1-4 lecture hours depending upon students<br />

background <strong>and</strong> level in the curriculum.<br />

Topics are organized to allow students to start laboratory work earlier in the<br />

semester.<br />

Sections begin with a topic list to help set thoughts.<br />

Objective given at the beginning of each chapter.<br />

Summary at the end of each chapter to give big picture.<br />

Significant use of figures to emphasize physical implementations.<br />

Worked examples <strong>and</strong> case studies.<br />

Problems at ends of chapters with solutions.<br />

Glossary.<br />

1.1 TODO LIST<br />

- Finish writing chapters<br />

* - structured text chapter<br />

* - FBD chapter<br />

- fuzzy logic chapter<br />

* - internet chapter<br />

- hmi chapter<br />

- modify chapters<br />

* - add topic hierarchies to this chapter. split into basics, logic design techniques,<br />

new stuff, integration, professional design for curriculum design<br />

* - electrical wiring chapter<br />

- fix wiring <strong>and</strong> other issues in the implementation chapter<br />

- software chapter - improve P&ID section<br />

- appendices - complete list of instruction data types in appendix<br />

- small items<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 1.4<br />

- update serial IO slides<br />

- all chapters<br />

* - grammar <strong>and</strong> spelling check<br />

* - update powerpoint slides<br />

* - add a resources web page with links<br />

- links to software/hardware vendors, iec1131, etc.<br />

- pictures of hardware <strong>and</strong> controls cabinet<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 2.1<br />

2. PROGRAMMABLE LOGIC CONTROLLERS<br />

Topics:<br />

• PLC History<br />

• Ladder Logic <strong>and</strong> Relays<br />

• PLC Programming<br />

• PLC Operation<br />

• An Example<br />

Objectives:<br />

• Know general PLC issues<br />

• To be able to write simple ladder logic programs<br />

• Underst<strong>and</strong> the operation of a PLC<br />

2.1 INTRODUCTION<br />

<strong>Control</strong> engineering has evolved over time. In the past humans were the main<br />

method for controlling a system. More recently electricity has been used for control <strong>and</strong><br />

early electrical control was based on relays. These relays allow power to be switched on<br />

<strong>and</strong> off without a mechanical switch. It is common to use relays to make simple logical<br />

control decisions. The development of low cost computer has brought the most recent revolution,<br />

the Programmable Logic <strong>Control</strong>ler (PLC). The advent of the PLC began in the<br />

1970s, <strong>and</strong> has become the most common choice for manufacturing controls.<br />

PLCs have been gaining popularity on the factory floor <strong>and</strong> will probably remain<br />

predominant for some time to come. Most of this is because of the advantages they offer.<br />

• Cost effective for controlling complex systems.<br />

• Flexible <strong>and</strong> can be reapplied to control other systems quickly <strong>and</strong> easily.<br />

• Computational abilities allow more sophisticated control.<br />

• Trouble shooting aids make programming easier <strong>and</strong> reduce downtime.<br />

• Reliable components make these likely to operate for years before failure.<br />

2.1.1 Ladder Logic<br />

Ladder logic is the main programming method used for PLCs. As mentioned<br />

before, ladder logic has been developed to mimic relay logic. The decision to use the relay<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 2.2<br />

logic diagrams was a strategic one. By selecting ladder logic as the main programming<br />

method, the amount of retraining needed for engineers <strong>and</strong> tradespeople was greatly<br />

reduced.<br />

Modern control systems still include relays, but these are rarely used for logic. A<br />

relay is a simple device that uses a magnetic field to control a switch, as pictured in Figure<br />

2.1. When a voltage is applied to the input coil, the resulting current creates a magnetic<br />

field. The magnetic field pulls a metal switch (or reed) towards it <strong>and</strong> the contacts touch,<br />

closing the switch. The contact that closes when the coil is energized is called normally<br />

open. The normally closed contacts touch when the input coil is not energized. Relays are<br />

normally drawn in schematic form using a circle to represent the input coil. The output<br />

contacts are shown with two parallel lines. Normally open contacts are shown as two<br />

lines, <strong>and</strong> will be open (non-conducting) when the input is not energized. Normally closed<br />

contacts are shown with two lines with a diagonal line through them. When the input coil<br />

is not energized the normally closed contacts will be closed (conducting).<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 2.3<br />

input coil<br />

OR<br />

normally<br />

closed<br />

normally<br />

open<br />

OR<br />

Figure 2.1<br />

Simple Relay Layouts <strong>and</strong> Schematics<br />

Relays are used to let one power source close a switch for another (often high current)<br />

power source, while keeping them isolated. An example of a relay in a simple control<br />

application is shown in Figure 2.2. In this system the first relay on the left is used as normally<br />

closed, <strong>and</strong> will allow current to flow until a voltage is applied to the input A. The<br />

second relay is normally open <strong>and</strong> will not allow current to flow until a voltage is applied<br />

to the input B. If current is flowing through the first two relays then current will flow<br />

through the coil in the third relay, <strong>and</strong> close the switch for output C. This circuit would<br />

normally be drawn in the ladder logic form. This can be read logically as C will be on if A<br />

is off <strong>and</strong> B is on.<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 2.4<br />

115VAC<br />

wall plug<br />

relay logic<br />

input A<br />

(normally closed)<br />

input B<br />

(normally open)<br />

output C<br />

(normally open)<br />

A B C<br />

ladder logic<br />

Figure 2.2<br />

A Simple Relay <strong>Control</strong>ler<br />

The example in Figure 2.2 does not show the entire control system, but only the<br />

logic. When we consider a PLC there are inputs, outputs, <strong>and</strong> the logic. Figure 2.3 shows a<br />

more complete representation of the PLC. Here there are two inputs from push buttons.<br />

We can imagine the inputs as activating 24V DC relay coils in the PLC. This in turn drives<br />

an output relay that switches 115V AC, that will turn on a light. Note, in actual PLCs<br />

inputs are never relays, but outputs are often relays. The ladder logic in the PLC is actually<br />

a computer program that the user can enter <strong>and</strong> change. Notice that both of the input push<br />

buttons are normally open, but the ladder logic inside the PLC has one normally open contact,<br />

<strong>and</strong> one normally closed contact. Do not think that the ladder logic in the PLC needs<br />

to match the inputs or outputs. Many beginners will get caught trying to make the ladder<br />

logic match the input types.<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 2.5<br />

push buttons<br />

power<br />

supply<br />

+24V<br />

com.<br />

PLC<br />

inputs<br />

ladder<br />

logic<br />

A B C<br />

outputs<br />

115Vac<br />

AC power<br />

light<br />

neut.<br />

Figure 2.3<br />

A PLC Illustrated With Relays<br />

Many relays also have multiple outputs (throws) <strong>and</strong> this allows an output relay to<br />

also be an input simultaneously. The circuit shown in Figure 2.4 is an example of this, it is<br />

called a seal in circuit. In this circuit the current can flow through either branch of the circuit,<br />

through the contacts labelled A or B. The input B will only be on when the output B<br />

is on. If B is off, <strong>and</strong> A is energized, then B will turn on. If B turns on then the input B will<br />

turn on, <strong>and</strong> keep output B on even if input A goes off. After B is turned on the output B<br />

will not turn off.<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 2.6<br />

A<br />

B<br />

B<br />

Note: When A is pushed, the output B will turn on, <strong>and</strong><br />

the input B will also turn on <strong>and</strong> keep B on permanently<br />

- until power is removed.<br />

Note: The line on the right is being left off intentionally<br />

<strong>and</strong> is implied in these diagrams.<br />

Figure 2.4<br />

A Seal-in Circuit<br />

2.1.2 Programming<br />

The first PLCs were programmed with a technique that was based on relay logic<br />

wiring schematics. This eliminated the need to teach the electricians, technicians <strong>and</strong> engineers<br />

how to program a computer - but, this method has stuck <strong>and</strong> it is the most common<br />

technique for programming PLCs today. An example of ladder logic can be seen in Figure<br />

2.5. To interpret this diagram imagine that the power is on the vertical line on the left h<strong>and</strong><br />

side, we call this the hot rail. On the right h<strong>and</strong> side is the neutral rail. In the figure there<br />

are two rungs, <strong>and</strong> on each rung there are combinations of inputs (two vertical lines) <strong>and</strong><br />

outputs (circles). If the inputs are opened or closed in the right combination the power can<br />

flow from the hot rail, through the inputs, to power the outputs, <strong>and</strong> finally to the neutral<br />

rail. An input can come from a sensor, switch, or any other type of sensor. An output will<br />

be some device outside the PLC that is switched on or off, such as lights or motors. In the<br />

top rung the contacts are normally open <strong>and</strong> normally closed. Which means if input A is on<br />

<strong>and</strong> input B is off, then power will flow through the output <strong>and</strong> activate it. Any other combination<br />

of input values will result in the output X being off.<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 2.7<br />

HOT<br />

A B X<br />

NEUTRAL<br />

C<br />

D<br />

G<br />

Y<br />

E<br />

F<br />

H<br />

INPUTS<br />

OUTPUTS<br />

Note: Power needs to flow through some combination of the inputs<br />

(A,B,C,D,E,F,G,H) to turn on outputs (X,Y).<br />

Figure 2.5<br />

A Simple Ladder Logic Diagram<br />

The second rung of Figure 2.5 is more complex, there are actually multiple combinations<br />

of inputs that will result in the output Y turning on. On the left most part of the<br />

rung, power could flow through the top if C is off <strong>and</strong> D is on. Power could also (<strong>and</strong><br />

simultaneously) flow through the bottom if both E <strong>and</strong> F are true. This would get power<br />

half way across the rung, <strong>and</strong> then if G or H is true the power will be delivered to output Y.<br />

In later chapters we will examine how to interpret <strong>and</strong> construct these diagrams.<br />

There are other methods for programming PLCs. One of the earliest techniques<br />

involved mnemonic instructions. These instructions can be derived directly from the ladder<br />

logic diagrams <strong>and</strong> entered into the PLC through a simple programming terminal. An<br />

example of mnemonics is shown in Figure 2.6. In this example the instructions are read<br />

one line at a time from top to bottom. The first line 00000 has the instruction LDN (input<br />

load <strong>and</strong> not) for input A. This will examine the input to the PLC <strong>and</strong> if it is off it will<br />

remember a 1 (or true), if it is on it will remember a 0 (or false). The next line uses an LD<br />

(input load) statement to look at the input. If the input is off it remembers a 0, if the input<br />

is on it remembers a 1 (note: this is the reverse of the LD). The AND statement recalls the<br />

last two numbers remembered <strong>and</strong> if the are both true the result is a 1, otherwise the result<br />

is a 0. This result now replaces the two numbers that were recalled, <strong>and</strong> there is only one<br />

number remembered. The process is repeated for lines 00003 <strong>and</strong> 00004, but when these<br />

are done there are now three numbers remembered. The oldest number is from the AND,<br />

the newer numbers are from the two LD instructions. The AND in line 00005 combines the<br />

results from the last LD instructions <strong>and</strong> now there are two numbers remembered. The OR<br />

instruction takes the two numbers now remaining <strong>and</strong> if either one is a 1 the result is a 1,<br />

otherwise the result is a 0. This result replaces the two numbers, <strong>and</strong> there is now a single<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 2.8<br />

number there. The last instruction is the ST (store output) that will look at the last value<br />

stored <strong>and</strong> if it is 1, the output will be turned on, if it is 0 the output will be turned off.<br />

00000<br />

00001<br />

00002<br />

00003<br />

00004<br />

00005<br />

00006<br />

LDN<br />

LD<br />

AND<br />

LD<br />

LD<br />

AND<br />

OR<br />

ST<br />

END<br />

A<br />

B<br />

C<br />

D<br />

00007 X<br />

00008<br />

A<br />

the mnemonic code is equivalent to<br />

the ladder logic below<br />

B<br />

X<br />

C<br />

D<br />

END<br />

Note: The notation shown above is<br />

not st<strong>and</strong>ard Allen-Bradley<br />

notation. The program to the<br />

right would be the A-B equivalent.<br />

SOR<br />

BST<br />

XIC A<br />

XIO B<br />

NXB<br />

XIO C<br />

XIO D<br />

BND<br />

OTE X<br />

EOR<br />

END<br />

Figure 2.6<br />

An Example of a Mnemonic Program <strong>and</strong> Equivalent Ladder Logic<br />

The ladder logic program in Figure 2.6, is equivalent to the mnemonic program.<br />

Even if you have programmed a PLC with ladder logic, it will be converted to mnemonic<br />

form before being used by the PLC. In the past mnemonic programming was the most<br />

common, but now it is uncommon for users to even see mnemonic programs.<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 2.9<br />

Sequential Function Charts (SFCs) have been developed to accommodate the programming<br />

of more advanced systems. These are similar to flowcharts, but much more<br />

powerful. The example seen in Figure 2.7 is doing two different things. To read the chart,<br />

start at the top where is says start. Below this there is the double horizontal line that says<br />

follow both paths. As a result the PLC will start to follow the branch on the left <strong>and</strong> right<br />

h<strong>and</strong> sides separately <strong>and</strong> simultaneously. On the left there are two functions the first one<br />

is the power up function. This function will run until it decides it is done, <strong>and</strong> the power<br />

down function will come after. On the right h<strong>and</strong> side is the flash function, this will run<br />

until it is done. These functions look unexplained, but each function, such as power up<br />

will be a small ladder logic program. This method is much different from flowcharts<br />

because it does not have to follow a single path through the flowchart.<br />

Start<br />

power up<br />

Execution follows<br />

multiple paths<br />

power down<br />

flash<br />

End<br />

Figure 2.7<br />

An Example of a Sequential Function Chart<br />

Structured Text programming has been developed as a more modern programming<br />

language. It is quite similar to languages such as BASIC. A simple example is shown in<br />

Figure 2.8. This example uses a PLC memory location i. This memory location is for an<br />

integer, as will be explained later in the book. The first line of the program sets the value<br />

to 0. The next line begins a loop, <strong>and</strong> will be where the loop returns to. The next line<br />

recalls the value in location i, adds 1 to it <strong>and</strong> returns it to the same location. The next line<br />

checks to see if the loop should quit. If i is greater than or equal to 10, then the loop will<br />

quit, otherwise the computer will go back up to the REPEAT statement continue from<br />

there. Each time the program goes through this loop i will increase by 1 until the value<br />

reaches 10.<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 2.10<br />

i := 0;<br />

REPEAT<br />

i := i + 1;<br />

UNTIL i >= 10<br />

END_REPEAT;<br />

Figure 2.8<br />

An Example of a Structured Text Program<br />

2.1.3 PLC Connections<br />

When a process is controlled by a PLC it uses inputs from sensors to make decisions<br />

<strong>and</strong> update outputs to drive actuators, as shown in Figure 2.9. The process is a real<br />

process that will change over time. Actuators will drive the system to new states (or modes<br />

of operation). This means that the controller is limited by the sensors available, if an input<br />

is not available, the controller will have no way to detect a condition.<br />

PROCESS<br />

Feedback from<br />

sensors/switches<br />

Connections to<br />

actuators<br />

PLC<br />

Figure 2.9<br />

The Separation of <strong>Control</strong>ler <strong>and</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

The control loop is a continuous cycle of the PLC reading inputs, solving the ladder<br />

logic, <strong>and</strong> then changing the outputs. Like any computer this does not happen<br />

instantly. Figure 2.10 shows the basic operation cycle of a PLC. When power is turned on<br />

initially the PLC does a quick sanity check to ensure that the hardware is working properly.<br />

If there is a problem the PLC will halt <strong>and</strong> indicate there is an error. For example, if<br />

the PLC power is dropping <strong>and</strong> about to go off this will result in one type of fault. If the<br />

PLC passes the sanity check it will then scan (read) all the inputs. After the inputs values<br />

are stored in memory the ladder logic will be scanned (solved) using the stored values -<br />

not the current values. This is done to prevent logic problems when inputs change during<br />

the ladder logic scan. When the ladder logic scan is complete the outputs will be scanned<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 2.11<br />

(the output values will be changed). After this the system goes back to do a sanity check,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the loop continues indefinitely. Unlike normal computers, the entire program will be<br />

run every scan. Typical times for each of the stages is in the order of milliseconds.<br />

PLC program changes outputs<br />

by examining inputs<br />

Read inputs<br />

THE<br />

CONTROL<br />

LOOP<br />

Set new outputs<br />

Power turned on<br />

<strong>Process</strong> changes <strong>and</strong> PLC pauses<br />

while it checks its own operation<br />

Figure 2.10<br />

The Scan Cycle of a PLC<br />

2.1.4 Ladder Logic Inputs<br />

PLC inputs are easily represented in ladder logic. In Figure 2.11 there are three<br />

types of inputs shown. The first two are normally open <strong>and</strong> normally closed inputs, discussed<br />

previously. The IIT (Immediate InpuT) function allows inputs to be read after the<br />

input scan, while the ladder logic is being scanned. This allows ladder logic to examine<br />

input values more often than once every cycle. (Note: This instruction is not available on<br />

the <strong>Control</strong>Logix processors, but is still available on older models.)<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 2.12<br />

x<br />

Normally open, an active input x will close the contact<br />

<strong>and</strong> allow power to flow.<br />

x<br />

Normally closed, power flows when the input x is not open.<br />

IIT<br />

x<br />

immediate inputs will take current values, not those from<br />

the previous input scan. (Note: this instruction is actually<br />

an output that will update the input table with the current<br />

input values. Other input contacts can now be used to<br />

examine the new values.)<br />

Figure 2.11<br />

Ladder Logic Inputs<br />

2.1.5 Ladder Logic Outputs<br />

In ladder logic there are multiple types of outputs, but these are not consistently<br />

available on all PLCs. Some of the outputs will be externally connected to devices outside<br />

the PLC, but it is also possible to use internal memory locations in the PLC. Six types of<br />

outputs are shown in Figure 2.12. The first is a normal output, when energized the output<br />

will turn on, <strong>and</strong> energize an output. The circle with a diagonal line through is a normally<br />

on output. When energized the output will turn off. This type of output is not available on<br />

all PLC types. When initially energized the OSR (One Shot Relay) instruction will turn on<br />

for one scan, but then be off for all scans after, until it is turned off. The L (latch) <strong>and</strong> U<br />

(unlatch) instructions can be used to lock outputs on. When an L output is energized the<br />

output will turn on indefinitely, even when the output coil is deenergized. The output can<br />

only be turned off using a U output. The last instruction is the IOT (Immediate OutpuT)<br />

that will allow outputs to be updated without having to wait for the ladder logic scan to be<br />

completed.<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 2.13<br />

When power is applied (on) the output x is activated for the left output, but turned<br />

off for the output on the right.<br />

x<br />

x<br />

An input transition on will cause the output x to go on for one scan<br />

(this is also known as a one shot relay)<br />

x<br />

OSR<br />

When the L coil is energized, x will be toggled on, it will stay on until the U coil<br />

is energized. This is like a flip-flop <strong>and</strong> stays set even when the PLC is turned off.<br />

x<br />

x<br />

L<br />

U<br />

Some PLCs will allow immediate outputs that do not wait for the program scan to<br />

end before setting an output. (Note: This instruction will only update the outputs using<br />

the output table, other instruction must change the individual outputs.)<br />

IOT<br />

x<br />

Note: Outputs are also commonly shown using parentheses -( )- instead of<br />

the circle. This is because many of the programming systems are text<br />

based <strong>and</strong> circles cannot be drawn.<br />

Figure 2.12<br />

Ladder Logic Outputs<br />

2.2 A CASE STUDY<br />

Problem: Try to develop (without looking at the solution) a relay based controller<br />

that will allow three switches in a room to control a single light.<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 2.14<br />

Solution: There are two possible approaches to this problem. The first assumes that any<br />

one of the switches on will turn on the light, but all three switches must be off for the<br />

light to be off.<br />

switch 1<br />

light<br />

switch 2<br />

switch 3<br />

The second solution assumes that each switch can turn the light on or off, regardless of<br />

the states of the other switches. This method is more complex <strong>and</strong> involves thinking<br />

through all of the possible combinations of switch positions. You might recognize<br />

this problem as an exclusive or problem.<br />

switch 1<br />

switch 2<br />

switch 3<br />

light<br />

switch 1<br />

switch 2<br />

switch 3<br />

switch 1<br />

switch 2<br />

switch 3<br />

switch 1 switch 2 switch 3<br />

Note: It is important to get a clear underst<strong>and</strong>ing of how the controls are expected to<br />

work. In this example two radically different solutions were obtained based upon a<br />

simple difference in the operation.<br />

2.3 SUMMARY<br />

• Normally open <strong>and</strong> closed contacts.<br />

• Relays <strong>and</strong> their relationship to ladder logic.<br />

• PLC outputs can be inputs, as shown by the seal in circuit.<br />

• Programming can be done with ladder logic, mnemonics, SFCs, <strong>and</strong> structured<br />

text.<br />

• There are multiple ways to write a PLC program.<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 2.15<br />

2.4 PRACTICE PROBLEMS<br />

1. Give an example of where a PLC could be used.<br />

2. Why would relays be used in place of PLCs?<br />

3. Give a concise description of a PLC.<br />

4. List the advantages of a PLC over relays.<br />

5. A PLC can effectively replace a number of components. Give examples <strong>and</strong> discuss some good<br />

<strong>and</strong> bad applications of PLCs.<br />

6. Explain why ladder logic outputs are coils?<br />

7. In the figure below, will the power for the output on the first rung normally be on or off? Would<br />

the output on the second rung normally be on or off?<br />

8. Write the mnemonic program for the Ladder Logic below.<br />

A<br />

Y<br />

B<br />

2.5 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS<br />

1. To control a conveyor system<br />

2. For simple designs<br />

3. A PLC is a computer based controller that uses inputs to monitor a process, <strong>and</strong> uses outputs to<br />

control a process using a program.<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 2.16<br />

4. Less expensive for complex processes, debugging tools, reliable, flexible, easy to exp<strong>and</strong>, etc.<br />

5. A PLC could replace a few relays. In this case the relays might be easier to install <strong>and</strong> less<br />

expensive. To control a more complex system the controller might need timing, counting <strong>and</strong><br />

other mathematical calculations. In this case a PLC would be a better choice.<br />

6. The ladder logic outputs were modelled on relay logic diagrams. The output in a relay ladder<br />

diagram is a relay coil that switches a set of output contacts.<br />

7. off, on<br />

8. Generic: LD A, LD B, OR, ST Y, END; Allen Bradley: SOR, BST, XIO A, NXB, XIO B,<br />

BND, OTE Y, EOR, END<br />

2.6 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS<br />

1. Explain the trade-offs between relays <strong>and</strong> PLCs for control applications.<br />

2. Develop a simple ladder logic program that will turn on an output X if inputs A <strong>and</strong> B, or input<br />

C is on.<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 3.1<br />

3. PLC HARDWARE<br />

Topics:<br />

• PLC hardware configurations<br />

• Input <strong>and</strong> outputs types<br />

• Electrical wiring for inputs <strong>and</strong> outputs<br />

• Relays<br />

• Electrical Ladder Diagrams <strong>and</strong> JIC wiring symbols<br />

Objectives:<br />

• Be able to underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> design basic input <strong>and</strong> output wiring.<br />

• Be able to produce industrial wiring diagrams.<br />

3.1 INTRODUCTION<br />

Many PLC configurations are available, even from a single vendor. But, in each of<br />

these there are common components <strong>and</strong> concepts. The most essential components are:<br />

Power Supply - This can be built into the PLC or be an external unit. Common<br />

voltage levels required by the PLC (with <strong>and</strong> without the power supply) are<br />

24Vdc, 120Vac, 220Vac.<br />

CPU (Central <strong>Process</strong>ing Unit) - This is a computer where ladder logic is stored<br />

<strong>and</strong> processed.<br />

I/O (Input/Output) - A number of input/output terminals must be provided so that<br />

the PLC can monitor the process <strong>and</strong> initiate actions.<br />

Indicator lights - These indicate the status of the PLC including power on, program<br />

running, <strong>and</strong> a fault. These are essential when diagnosing problems.<br />

The configuration of the PLC refers to the packaging of the components. Typical<br />

configurations are listed below from largest to smallest as shown in Figure 3.1.<br />

Rack - A rack is often large (up to 18” by 30” by 10”) <strong>and</strong> can hold multiple cards.<br />

When necessary, multiple racks can be connected together. These tend to be the<br />

highest cost, but also the most flexible <strong>and</strong> easy to maintain.<br />

Mini - These are smaller than full sized PLC racks, but can have the same IO<br />

capacity.<br />

Micro - These units can be as small as a deck of cards. They tend to have fixed<br />

quantities of I/O <strong>and</strong> limited abilities, but costs will be the lowest.<br />

Software - A software based PLC requires a computer with an interface card, but<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 3.2<br />

allows the PLC to be connected to sensors <strong>and</strong> other PLCs across a network.<br />

rack<br />

mini<br />

micro<br />

Figure 3.1<br />

Typical Configurations for PLC<br />

3.2 INPUTS AND OUTPUTS<br />

Inputs to, <strong>and</strong> outputs from, a PLC are necessary to monitor <strong>and</strong> control a process.<br />

Both inputs <strong>and</strong> outputs can be categorized into two basic types: logical or continuous.<br />

Consider the example of a light bulb. If it can only be turned on or off, it is logical control.<br />

If the light can be dimmed to different levels, it is continuous. Continuous values seem<br />

more intuitive, but logical values are preferred because they allow more certainty, <strong>and</strong><br />

simplify control. As a result most controls applications (<strong>and</strong> PLCs) use logical inputs <strong>and</strong><br />

outputs for most applications. Hence, we will discuss logical I/O <strong>and</strong> leave continuous I/O<br />

for later.<br />

Outputs to actuators allow a PLC to cause something to happen in a process. A<br />

short list of popular actuators is given below in order of relative popularity.<br />

Solenoid Valves - logical outputs that can switch a hydraulic or pneumatic flow.<br />

Lights - logical outputs that can often be powered directly from PLC output<br />

boards.<br />

Motor Starters - motors often draw a large amount of current when started, so they<br />

require motor starters, which are basically large relays.<br />

Servo Motors - a continuous output from the PLC can comm<strong>and</strong> a variable speed<br />

or position.<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 3.3<br />

Outputs from PLCs are often relays, but they can also be solid state electronics<br />

such as transistors for DC outputs or Triacs for AC outputs. Continuous outputs require<br />

special output cards with digital to analog converters.<br />

Inputs come from sensors that translate physical phenomena into electrical signals.<br />

Typical examples of sensors are listed below in relative order of popularity.<br />

Proximity Switches - use inductance, capacitance or light to detect an object logically.<br />

Switches - mechanical mechanisms will open or close electrical contacts for a logical<br />

signal.<br />

Potentiometer - measures angular positions continuously, using resistance.<br />

LVDT (linear variable differential transformer) - measures linear displacement<br />

continuously using magnetic coupling.<br />

Inputs for a PLC come in a few basic varieties, the simplest are AC <strong>and</strong> DC inputs.<br />

Sourcing <strong>and</strong> sinking inputs are also popular. This output method dictates that a device<br />

does not supply any power. Instead, the device only switches current on or off, like a simple<br />

switch.<br />

Sinking - When active the output allows current to flow to a common ground. This<br />

is best selected when different voltages are supplied.<br />

Sourcing - When active, current flows from a supply, through the output device<br />

<strong>and</strong> to ground. This method is best used when all devices use a single supply<br />

voltage.<br />

This is also referred to as NPN (sinking) <strong>and</strong> PNP (sourcing). PNP is more popular.<br />

This will be covered in detail in the chapter on sensors.<br />

3.2.1 Inputs<br />

In smaller PLCs the inputs are normally built in <strong>and</strong> are specified when purchasing<br />

the PLC. For larger PLCs the inputs are purchased as modules, or cards, with 8 or 16<br />

inputs of the same type on each card. For discussion purposes we will discuss all inputs as<br />

if they have been purchased as cards. The list below shows typical ranges for input voltages,<br />

<strong>and</strong> is roughly in order of popularity.<br />

12-24 Vdc<br />

100-120 Vac<br />

10-60 Vdc<br />

12-24 Vac/dc<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 3.4<br />

5 Vdc (TTL)<br />

200-240 Vac<br />

48 Vdc<br />

24 Vac<br />

PLC input cards rarely supply power, this means that an external power supply is<br />

needed to supply power for the inputs <strong>and</strong> sensors. The example in Figure 3.2 shows how<br />

to connect an AC input card.<br />

24 V AC<br />

Power<br />

Supply<br />

Hot<br />

Neut.<br />

normally open push-button<br />

PLC Input Card<br />

24V AC<br />

00<br />

01<br />

02<br />

03<br />

04<br />

normally open<br />

temperature switch<br />

05<br />

06<br />

07<br />

COM<br />

Pushbutton (bob:3:I.Data.1)<br />

it is in rack "bob"<br />

slot 3<br />

Tempsensor (bob:3:I.Data.3)<br />

Note: inputs are normally high impedance. This means that they will<br />

use very little current.<br />

Figure 3.2<br />

An AC Input Card <strong>and</strong> Ladder Logic<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 3.5<br />

In the example there are two inputs, one is a normally open push button, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

second is a temperature switch, or thermal relay. (NOTE: These symbols are st<strong>and</strong>ard <strong>and</strong><br />

will be discussed later in this chapter.) Both of the switches are powered by the positive/<br />

hot output of the 24Vac power supply - this is like the positive terminal on a DC supply.<br />

Power is supplied to the left side of both of the switches. When the switches are open there<br />

is no voltage passed to the input card. If either of the switches are closed power will be<br />

supplied to the input card. In this case inputs 1 <strong>and</strong> 3 are used - notice that the inputs start<br />

at 0. The input card compares these voltages to the common. If the input voltage is within<br />

a given tolerance range the inputs will switch on. Ladder logic is shown in the figure for<br />

the inputs. Here it uses Allen Bradley notation for <strong>Control</strong>Logix. At the top is the tag<br />

(variable name) for the rack. The input card (’I’) is in slot 3, so the address for the card is<br />

bob:3.I.Data.x, where ’x’ is the input bit number. These addresses can also be given alias<br />

tags to make the ladder logic less confusing.<br />

NOTE: The design process will be much easier if the inputs <strong>and</strong> outputs are planned first,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the tags are entered before the ladder logic. Then the program is entered using the<br />

much simpler tag names.<br />

Many beginners become confused about where connections are needed in the circuit<br />

above. The key word to remember is circuit, which means that there is a full loop that<br />

the voltage must be able to follow. In Figure 3.2 we can start following the circuit (loop) at<br />

the power supply. The path goes through the switches, through the input card, <strong>and</strong> back to<br />

the power supply where it flows back through to the start. In a full PLC implementation<br />

there will be many circuits that must each be complete.<br />

A second important concept is the common. Here the neutral on the power supply<br />

is the common, or reference voltage. In effect we have chosen this to be our 0V reference,<br />

<strong>and</strong> all other voltages are measured relative to it. If we had a second power supply, we<br />

would also need to connect the neutral so that both neutrals would be connected to the<br />

same common. Often common <strong>and</strong> ground will be confused. The common is a reference,<br />

or datum voltage that is used for 0V, but the ground is used to prevent shocks <strong>and</strong> damage<br />

to equipment. The ground is connected under a building to a metal pipe or grid in the<br />

ground. This is connected to the electrical system of a building, to the power outlets,<br />

where the metal cases of electrical equipment are connected. When power flows through<br />

the ground it is bad. Unfortunately many engineers, <strong>and</strong> manufacturers mix up ground <strong>and</strong><br />

common. It is very common to find a power supply with the ground <strong>and</strong> common mislabeled.<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 3.6<br />

Remember - Don’t mix up the ground <strong>and</strong> common. Don’t connect them together if the<br />

common of your device is connected to a common on another device.<br />

One final concept that tends to trap beginners is that each input card is isolated.<br />

This means that if you have connected a common to only one card, then the other cards are<br />

not connected. When this happens the other cards will not work properly. You must connect<br />

a common for each of the output cards.<br />

There are many trade-offs when deciding which type of input cards to use.<br />

• DC voltages are usually lower, <strong>and</strong> therefore safer (i.e., 12-24V).<br />

• DC inputs are very fast, AC inputs require a longer on-time. For example, a 60Hz<br />

wave may require up to 1/60sec for reasonable recognition.<br />

• DC voltages can be connected to larger variety of electrical systems.<br />

• AC signals are more immune to noise than DC, so they are suited to long distances,<br />

<strong>and</strong> noisy (magnetic) environments.<br />

• AC power is easier <strong>and</strong> less expensive to supply to equipment.<br />

• AC signals are very common in many existing automation devices.<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 3.7<br />

ASIDE: PLC inputs must convert a variety of logic levels to the 5Vdc logic levels<br />

used on the data bus. This can be done with circuits similar to those shown below.<br />

Basically the circuits condition the input to drive an optocoupler. This electrically<br />

isolates the external electrical circuitry from the internal circuitry. Other circuit<br />

components are used to guard against excess or reversed voltage polarity.<br />

+5V<br />

+<br />

optocoupler<br />

DC<br />

input<br />

TTL<br />

COM<br />

hot<br />

neut.<br />

AC<br />

input<br />

+5V<br />

optocoupler<br />

TTL<br />

Figure 3.3<br />

Aside: PLC Input Circuits<br />

3.2.2 Output Modules<br />

WARNING - ALWAYS CHECK RATED VOLTAGES AND CURRENTS FOR PLC’s<br />

AND NEVER EXCEED!<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 3.8<br />

As with input modules, output modules rarely supply any power, but instead act as<br />

switches. External power supplies are connected to the output card <strong>and</strong> the card will<br />

switch the power on or off for each output. Typical output voltages are listed below, <strong>and</strong><br />

roughly ordered by popularity.<br />

120 Vac<br />

24 Vdc<br />

12-48 Vac<br />

12-48 Vdc<br />

5Vdc (TTL)<br />

230 Vac<br />

These cards typically have 8 to 16 outputs of the same type <strong>and</strong> can be purchased<br />

with different current ratings. A common choice when purchasing output cards is relays,<br />

transistors or triacs. Relays are the most flexible output devices. They are capable of<br />

switching both AC <strong>and</strong> DC outputs. But, they are slower (about 10ms switching is typical),<br />

they are bulkier, they cost more, <strong>and</strong> they will wear out after millions of cycles. Relay<br />

outputs are often called dry contacts. Transistors are limited to DC outputs, <strong>and</strong> Triacs are<br />

limited to AC outputs. Transistor <strong>and</strong> triac outputs are called switched outputs.<br />

Dry contacts - a separate relay is dedicated to each output. This allows mixed voltages<br />

(AC or DC <strong>and</strong> voltage levels up to the maximum), as well as isolated outputs<br />

to protect other outputs <strong>and</strong> the PLC. Response times are often greater than<br />

10ms. This method is the least sensitive to voltage variations <strong>and</strong> spikes.<br />

Switched outputs - a voltage is supplied to the PLC card, <strong>and</strong> the card switches it to<br />

different outputs using solid state circuitry (transistors, triacs, etc.) Triacs are<br />

well suited to AC devices requiring less than 1A. Transistor outputs use NPN or<br />

PNP transistors up to 1A typically. Their response time is well under 1ms.<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 3.9<br />

ASIDE: PLC outputs must convert the 5Vdc logic levels on the PLC data bus to external<br />

voltage levels. This can be done with circuits similar to those shown below.<br />

Basically the circuits use an optocoupler to switch external circuitry. This electrically<br />

isolates the external electrical circuitry from the internal circuitry. Other circuit<br />

components are used to guard against excess or reversed voltage polarity.<br />

optocoupler<br />

+V<br />

TTL<br />

Sourcing DC output<br />

TTL<br />

optocoupler<br />

AC<br />

output<br />

TTL<br />

+V<br />

relay<br />

output<br />

AC/DC<br />

Note: Some AC outputs will<br />

also use zero voltage detection.<br />

This allows the output<br />

to be switched on when the<br />

voltage <strong>and</strong> current are<br />

effectively off, thus preventing<br />

surges.<br />

Figure 3.4<br />

Aside: PLC Output Circuits<br />

Caution is required when building a system with both AC <strong>and</strong> DC outputs. If AC is<br />

www.PA<strong>Control</strong>.com

plc wiring - 3.10<br />

accidentally connected to a DC transistor output it will only be on for the positive half of<br />

the cycle, <strong>and</strong> appear to be working with a diminished voltage. If DC is connected to an<br />

AC triac output it will turn on <strong>and</strong> appear to work, but you will not be able to turn it off<br />

without turning off the entire PLC.<br />