Immunotherapy Safety for the Primary Care ... - U.S. Coast Guard

Immunotherapy Safety for the Primary Care ... - U.S. Coast Guard

Immunotherapy Safety for the Primary Care ... - U.S. Coast Guard

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> <strong>Safety</strong> <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Provider<br />

To begin, click <strong>the</strong> Bookmark Tab or Icon to <strong>the</strong> left<br />

to open <strong>the</strong> Table of Contents. Click on <strong>the</strong> + next to<br />

a topic to reveal <strong>the</strong> available slideshow & reference<br />

articles. Open your selection by moving <strong>the</strong> cursor<br />

over <strong>the</strong> title and left click once.<br />

Left click with <strong>the</strong> cursor positioned over <strong>the</strong> first<br />

page/slide, <strong>the</strong>n use <strong>the</strong> Page Up/Down keys to<br />

proceed through <strong>the</strong> presentation. When an item is<br />

complete, an “end of selection” page will appear.<br />

I hope you find this material useful & <strong>the</strong> CD <strong>for</strong>mat<br />

convenient.<br />

Capt. J. Montgomery MC, USN<br />

February 04, 2008

End of Selection<br />

Go to Bookmarks &<br />

select ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

presentation or<br />

reference article

Welcome to<br />

“<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> <strong>Safety</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Provider” or “Optimizing <strong>the</strong> <strong>Safety</strong> of<br />

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Administration Outside of <strong>the</strong> Allergist’s Office”<br />

I am deeply indebted to <strong>the</strong> American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology’s<br />

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> & Allergy Diagnostics Committee and to <strong>the</strong> Immunization and Allergy<br />

Specialty Course of <strong>the</strong> Walter Reed Army Medical Center <strong>for</strong> much of <strong>the</strong> material<br />

contained within this training CD.<br />

The purpose of this CD is to provide a comprehensive overview of allergen<br />

immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy <strong>for</strong> primary care physicians and <strong>the</strong>ir ancillary staff with a primary focus<br />

on risk factors that affect immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy safety and measures that may enhance<br />

immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy safety.<br />

Learning Objectives:<br />

1. Understand immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy indications, potential risks, contraindications,<br />

protocols, potential mechanisms and risk factors <strong>for</strong> systemic reactions after<br />

allergen and vaccination injections.<br />

2. Be familiar with <strong>the</strong> current recommended guidelines in terms of proper personnel<br />

and emergency equipment required <strong>for</strong> administration of allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

and adult and pediatric vaccines.<br />

3. Recognize <strong>the</strong> signs and symptoms of adverse immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy reactions and <strong>the</strong><br />

appropriate treatment <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

4. Apply <strong>the</strong> greater understanding of potential risks associated with immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

and immunizations into a clinical practice with office protocols designed to screen<br />

high risk individuals prior to receiving injections and to make appropriate clinical<br />

decisions based on this screen.<br />

5. Apply <strong>the</strong> competencies and learning assessments contained herein to assure<br />

<strong>the</strong> safe administration of immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy and vaccines.<br />

CD <strong>for</strong>mat: The didactic program begins with <strong>the</strong> lecture slide show. Handouts include<br />

a lecture summary and a position statement addressing administration of allergen<br />

immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy by non-physician staff, as well as suggested <strong>for</strong>mats <strong>for</strong> a clinic SOP,<br />

nurse/technician competency assessment, patient in<strong>for</strong>med consent, AIT administration<br />

<strong>for</strong>m, and a dosage adjustment guide. Upon completion of this program, participants<br />

are encouraged to take <strong>the</strong> included self-assessment test.<br />

I hope that you find <strong>the</strong> material helpful and <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mat convenient.<br />

Capt. Jay Montgomery MC, USN<br />

Head, Division of Allergy & Immunology<br />

National Naval Medical Center<br />

Production Team: Ms. Sally Bentsi-Enchill, HM3 Harrison Wright USN, Ms. Anna<br />

Harrison, Ms. Denise Chambers, and HN Joy Lewis USN

End of Selection<br />

Go to Bookmarks &<br />

select ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

presentation or<br />

reference article

Click <strong>the</strong> ⌧ next to <strong>the</strong><br />

topic to view <strong>the</strong> slide<br />

show & reference articles

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Provider<br />

-or-<br />

Optimizing The <strong>Safety</strong> Of <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Administration<br />

Outside Of The Prescribing Allergist’s Office<br />

Jay Montgomery MD, FAAFP, FAAAAI<br />

Captain, Medical Corps, United States Navy<br />

Head, Division of Allergy & Immunology<br />

National Naval Medical Center

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> at Remote Sites<br />

Standard of <strong>Care</strong><br />

• In <strong>the</strong> case of professionals, <strong>the</strong> standard<br />

of care refers to <strong>the</strong> level of care that a<br />

reasonable professional in <strong>the</strong> same or<br />

similar circumstances would take to<br />

prevent harm or injury to ano<strong>the</strong>r person.<br />

• “The standard of care concerning <strong>the</strong><br />

administration of immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy should be<br />

<strong>the</strong> same regardless of where <strong>the</strong><br />

immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy is given and <strong>the</strong> specialty<br />

of <strong>the</strong> supervising physician.”<br />

Position Statement on administration of immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy outside of <strong>the</strong> prescribing allergist facility. Drug<br />

and Anaphylaxis Committee of ACAAI. Ann Allergy Asthma and Immunol 1998;81:101-102

What is <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong>?<br />

• Gradually increasing quantities of specific<br />

allergens to an optimal dose<br />

• Raises <strong>the</strong> patient’s tolerance to <strong>the</strong><br />

allergens<br />

• Thereby minimizing <strong>the</strong> symptomatic<br />

expression of <strong>the</strong> allergic disease<br />

• Allergen extract vs Allergen vaccine<br />

– Proteins ‘extracted’ from various materials<br />

– ‘Immune modifier’

What <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Is Not<br />

• Not prescribed by a remote laboratory:<br />

– <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> should be prescribed by physicians<br />

specifically trained to diagnosis and treat allergic<br />

diseases.<br />

• Not based on skin test or in vitro tests alone:<br />

– Treatment MUST be based on <strong>the</strong> combination of a<br />

thorough history and physical exam and allergy tests.<br />

• Not administered at home<br />

– Must be administered in a properly equipped facility<br />

staffed with personal able to recognize/ treat IT systemic<br />

reactions.

What <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Is Not<br />

• Not administered through non-injectable<br />

routes<br />

– Subcutaneous route is <strong>the</strong> only approved method in <strong>the</strong><br />

U.S.; sublingual route currently is not approved by FDA.<br />

– Sublingual immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy used outside of US, but with<br />

higher doses (10- 500 x subcutaneous IT) may make<br />

treatment cost prohibitive. Fur<strong>the</strong>r studies required<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e approved in US.

How Does <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Work?<br />

• Decrease in cellular responsiveness<br />

• Production of blocking antibody<br />

• Induction of tolerance (B-cell,<br />

T-cell, or both)<br />

• Presence of anti-idiotypic<br />

antibodies<br />

• Activation of T-cell suppressor<br />

mechanism

History of <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong><br />

1911<br />

• Leonard Noon at <strong>the</strong> St. Mary’s Hospital,<br />

London injected extract of grass pollen<br />

into a patient whose symptoms coincided<br />

with <strong>the</strong> pollinating season of grasses<br />

1965-present<br />

• Norman, Lichtenstein, et. al. defined AIT<br />

effectiveness in allergic rhinitis, allergic<br />

conjunctivitis, allergic asthma, and<br />

hymenoptera hypersensitivity

Who Benefits?<br />

•Those with…<br />

– Allergic disease identified through an<br />

adequate history & in vivo testing (in vitro<br />

testing is not adequately specific)<br />

– Well-defined clinically relevant allergic triggers<br />

– Significant effect on quality of life or daily<br />

function<br />

– Inadequate relief through avoidance<br />

measures and pharmaco<strong>the</strong>rapy

What Benefits?<br />

• Marked reduction in allergy symptom scores<br />

• Marked reduction in medication use<br />

• Reduced sensitivity to o<strong>the</strong>r allergens<br />

• May prevent progression or development of<br />

multiple allergies<br />

• May reduce risk of later development of<br />

asthma

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Efficacy<br />

• Effective treatment <strong>for</strong> allergic rhinitis<br />

– A meta-analysis of 18 studies involving 789 patients concluded that<br />

AIT is effective in <strong>the</strong> treatment of allergic rhinitis. 1<br />

• Effective treatment <strong>for</strong> asthma<br />

– Two meta-analyses of 43 prospective studies showed that AIT is<br />

effective in <strong>the</strong> treatment of allergic asthma. 2,3,4<br />

• Highly effective treatment <strong>for</strong> insect venom allergy<br />

– A meta-analysis of 9 studies indicated that a course of venom<br />

immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy (VIT) is highly effective in <strong>the</strong> management of<br />

insect sting hypersensitivity. 5,6

Indications <strong>for</strong> <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong><br />

• Hymenoptera venom hypersensitivity,<br />

allergic rhinitis, allergic conjunctivitis, and<br />

allergic asthma<br />

• Desire to avoid long-term use or potential<br />

adverse effects of medications<br />

• Symptoms not adequately controlled by<br />

avoidance and pharmaco<strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

• Cost of immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy is less than cost of<br />

long-term medications

Not Efficacious For…<br />

• Atopic dermatitis<br />

• Urticaria<br />

• Headaches<br />

• Food allergies

Allergen <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong><br />

<strong>Safety</strong>

The Extracts/Vaccines<br />

• Bioequivalent Allergy Unit (BAU)<br />

– Determined through quantitative skin testing on<br />

a reference population of allergic patients<br />

highly skin-test reactive to that allergen<br />

• Standardized Allergens<br />

– Cat, Bermuda & Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Pasture Grasses (3),<br />

Dust Mite (2), and Ragweed<br />

• Non-standardized Allergens<br />

– Wt/V or PNU

The Extracts<br />

• Storage<br />

– Refrigerated at 4°C (39°F)<br />

• Loss of potency within weeks at room temp<br />

• More concentrated = more stable<br />

• Identification<br />

– Name & identifying number (SSN, DOB, etc.)<br />

– Contents of vial<br />

• Tree: T, Mold: M, Grass: G, Cat: C, Weed: W,<br />

Dog: D, Ragweed: R, Cockroach: Cr, Dust Mite: Dm<br />

– Expiration date<br />

– Dilution v/v (from maintenance vial)<br />

– Number identifier (#1=maintenance=red cap)<br />

– Standard colored caps<br />

• Red= 1:1, yellow= 1:10, blue= 1:100, green= 1:1,000

Lots of Numbers!<br />

Vial v/v W/V<br />

(example)<br />

AU/ML<br />

(example)<br />

BAU/ML<br />

(example)<br />

1<br />

Red<br />

2<br />

Gold<br />

3<br />

Blue<br />

4<br />

Green<br />

5<br />

Silver<br />

1:1<br />

(maintenance)<br />

1:10<br />

1:100<br />

1:1000<br />

1:10,000<br />

1:100 2000 7750<br />

1:1,000 200 775<br />

1:10,000 20 77.5<br />

1:100,000 2 7.75<br />

1:1,000,000 0.2 .775

Dilution Labeling, Color-<br />

Coding and Vial Nomenclature<br />

Patient’s name on all vials<br />

Contents<br />

Vial concentration<br />

Expiration date

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Phases<br />

• Maintenance concentration = <strong>the</strong>rapeutically effective dose<br />

as determined by <strong>the</strong> Allergist<br />

• Build up phase (vials up to & including maintenance vial)<br />

– Involves receiving injections of increasing amounts of allergen(s)<br />

– Frequency of injections ranges from 1 - 2 times a week, although<br />

more rapid build-up schedules are possible.<br />

– The duration of this phase generally ranges from 3 to 6 months,<br />

depending upon <strong>the</strong> frequency of <strong>the</strong> 18-27 injections.<br />

• Maintenance phase (maintenance vial)<br />

– Begins when <strong>the</strong> effective <strong>the</strong>rapeutic dose is reached.<br />

– Differs <strong>for</strong> each person, depending on <strong>the</strong>ir level of allergen<br />

sensitivity (how 'allergic’ <strong>the</strong>y are to <strong>the</strong> allergens in <strong>the</strong>ir vaccine)<br />

and <strong>the</strong>ir response to <strong>the</strong> build-up phase.<br />

– The intervals between maintenance immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy injections<br />

generally ranges from 2 to 4 weeks (3-4 weeks).<br />

– Administered <strong>for</strong> 3-5 years.<br />

• AIT schedules ≠ VIT schedules

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Reactions<br />

Local reactions:<br />

• Are fairly common<br />

• Present as redness and<br />

swelling at <strong>the</strong> injection<br />

site.<br />

• Can happen immediately,<br />

or several hours after<br />

injections.<br />

Systemic reactions:<br />

• Less common<br />

• Include allergy symptoms such as sneezing,<br />

itching palms, nasal congestion, or hives.<br />

• Can include swelling in <strong>the</strong> throat, wheezing<br />

or a sensation of tightness in <strong>the</strong> chest,<br />

nausea, dizziness, fainting, and/or o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

severe systemic symptoms.<br />

• Systemic reactions require immediate<br />

treatment.

Reaction Prevention - Avoidance<br />

• Circumstances warranting dose change<br />

– Follow prescribing Allergist’s written instructions<br />

– Missed doses<br />

– Buildup phase<br />

– Maintenance phase<br />

– Reactions, local or systemic<br />

• Local >1” (quarter size) or lasts >12 hr<br />

• Systemic<br />

– Renewed maintenance vial - reduce dose 50%<br />

– Communication with Allergist ALWAYS!

Reaction Therapy – BLS+ Level<br />

• Treatment of local<br />

reactions<br />

– Local reaction<br />

• Cold pack, oral<br />

antihistamine, topical<br />

steroid<br />

– Large local reaction<br />

(Arthus reaction)<br />

• Oral steroids, NSAIDs, oral<br />

antihistamines

Reaction Therapy – BLS+ Level<br />

• Treatment of systemic reactions<br />

– Anaphylaxis 3%, Death 1:1,000,000<br />

• Training and Equipment <strong>for</strong> Basic Life Support<br />

• Physician at bedside w/in 2-3 minutes<br />

• ABC assessment TO BE PERFORMED<br />

AT THE SAME TIME AS THE<br />

ADMINISTRATION OF<br />

EPINEPHRINE

Treatment Guidelines<br />

• Treatment (airway/breathing)<br />

– Maintain an open airway<br />

– High flow oxygen (4-10 l/m) with pulse oximetry<br />

– Intubation when PaCO 2 >65 mm Hg / SaO 2 90 mm Hg<br />

– Place patient in Trendelenburg position<br />

– Insertion of large-bore IV<br />

• 0.9% saline<br />

– Severe Hypotension<br />

• Dextran, Hetastarch

Treatment Guidelines<br />

• Treatment (drugs)<br />

– EPINEPHRINE<br />

• 0.3 - 0.5 cc 1:1,000 IM adult<br />

• 0.01cc/kg 1:1,000 IM child<br />

• Repeat q 10 min prn<br />

• Glucagon 1-5 mg over 2-5 min IV push<br />

– Antihistamines<br />

• Diphenhydramine (Benadryl): 50-75 mg IM/IV adult<br />

1-2mg/kg IM/IV child<br />

• Cimetidine (Zantac): 300 mg q6-8 hr PO/IV<br />

– For Bronchospasm - Albuterol MDI/Nebulized<br />

– Methylprednisolone 60 - 80 mg IV

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Contraindications<br />

•Who?<br />

– Conditions posing reaction survivability risk<br />

• Lung disease with FEV 1

Frequency of Systemic Reactions<br />

• 0.8% to 46.7% (mean 12.92%) systemic reaction<br />

rate <strong>for</strong> conventional AIT schedule.<br />

Stewart GE and Lockey RF J Allergy Clin Immunol 1992; 90: 567-78<br />

• 45% of reactions occur in patients who have had<br />

previous systemic reactions.<br />

Matloff SM et al Allergy Proceed 1993; 14: 347-350

Worse Case Scenario: Fatalities<br />

• 46 fatalities between 1945 and 1984<br />

• 10 fatalities during seasonal exacerbation<br />

• 4 fatalities in patients symptomatic prior to injection<br />

• 22/30 onset of reaction within 30 minutes<br />

Lockey RF, et. al., J Allergy Clin Immunol 1987; 79: 660-77<br />

• 17 fatalities between 1985 and 1989<br />

• 76% had asthma, 36% reported prior systemic reactions<br />

• 5 – new vial, 5 – dosing error, 4 – prior symptoms<br />

• 11/17 onset anaphylaxis within 20 minutes<br />

Reid MJ, et. Al., J Allergy Clin Immunol 1993; 92: 6-15<br />

• 41 fatalities between 1990 and 2001<br />

• Death rate of 1 per 2,540,000 injections, 3.4 deaths per year<br />

• 15 were asthmatic not optimally controlled<br />

• 3 deaths in patients receiving AIT outside of a medical facility<br />

• Most occurred with maintenance concentrates<br />

Bernstein DI, et al., J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 113: 1129-36

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> <strong>Safety</strong><br />

• To lessen risk of reaction<br />

– Identify patient (100%)<br />

– Check health status<br />

• Acutely ill, asthma/allergy exacerbation, new medications?<br />

• Previous delayed reactions?<br />

– Use standard immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy administration <strong>for</strong>m<br />

• Right Patient (check ID)<br />

• Right Extract (extract contents / Rx number must be on vial)<br />

• Right Strength (extract cap color, written concentration)<br />

• Right Time (date of injection is within prescribed schedule)<br />

• Right Dose (have patient verify vial # and amount drawn)<br />

– Document everything!

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> <strong>Safety</strong><br />

• To lessen risk of reaction<br />

– Allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy should be given in settings where<br />

emergency resuscitative equipment and trained personnel are<br />

immediately available to treat systemic reactions under <strong>the</strong><br />

supervision of a physician or licensed physician extender.”<br />

– Patients at high risk <strong>for</strong> systemic reactions (those who are highly<br />

sensitive or have severe symptoms, co-morbid conditions, or a<br />

history of recurrent reactions) should receive immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy in<br />

<strong>the</strong> office of <strong>the</strong> Allergist. The Allergist who prepared <strong>the</strong><br />

patient’s vaccine and <strong>the</strong> support staff should have experience<br />

and procedures in place <strong>for</strong> administering immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy to<br />

high-risk patients.<br />

- Position Statement On: Administration Of <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Outside Of The Prescribing Allergist<br />

Facility. Ann Allergy Asthma and Immunol 1998;81:101-102<br />

- Allergen <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong>: a practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma and Immunol 2003;90:1-40

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> <strong>Safety</strong><br />

• To lessen risk of reaction<br />

– Trained personnel should be familiar with <strong>the</strong><br />

following procedures:<br />

• Adjustment of dose of allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

extract to minimize reactions.<br />

• Recognition and treatment of local and systemic<br />

reactions to immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy injections.<br />

• Basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation.<br />

• Ongoing patient education in recognition and<br />

treatment of local and systemic reactions that<br />

occur outside <strong>the</strong> Allergist's office.”

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> <strong>Safety</strong><br />

• Injection<br />

– Once patient and extract verified …<br />

• Wipe injection site (<strong>the</strong> dorsal aspect of upper arm, halfway<br />

between elbow and shoulder).<br />

• Wipe extract tops with alcohol, draw up extracts per protocol.<br />

• With gloved hands, administer injections subcutaneously at a<br />

90° angle with 1/2 - 5/8 inch needle or 45° angle with 1 inch<br />

needle after first drawing back plunger & checking <strong>for</strong> blood.<br />

• Hold 2x2 on site firmly <strong>for</strong> a few seconds. Do not rub.<br />

• Dispose of syringe and needle in <strong>the</strong> sharps container.<br />

• NEVER RE-CAP NEEDLES.<br />

• Apply band aid/ice/ topical steroid cream, if needed.

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> <strong>Safety</strong><br />

• After Injection<br />

– After 30 minutes, examine <strong>the</strong> injection sites <strong>for</strong><br />

induration and/or ery<strong>the</strong>ma.<br />

– Document all findings on <strong>the</strong> AIT shot record.<br />

– Document any protocol-directed dose reductions of<br />

future injections on <strong>the</strong> AIT shot record and SF-600.<br />

– If needed, fur<strong>the</strong>r modify dose reduction instructions<br />

as per delayed reaction dose-reduction protocol.

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> <strong>Safety</strong><br />

• Patient instructions:<br />

– Must remain in clinic 30 minutes after injection.<br />

– Have staff inspect site(s) <strong>for</strong> swelling be<strong>for</strong>e leaving.<br />

– Report any abnormal signs or symptoms to staff<br />

immediately.<br />

– Don’t exercise <strong>for</strong> 2 hrs after receiving AIT.<br />

– Notify staff prior to next shot of any delayed reaction.<br />

– Keep to <strong>the</strong>ir AIT/VIT schedule.

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> <strong>Safety</strong><br />

• Equipment:<br />

• Aeroallergen & venom extract<br />

storage (4º C refrigerator with<br />

alarm)<br />

• 1 ml (<strong>for</strong> AIT) & 3ml (<strong>for</strong> VIT)<br />

disposable (safety) syringes<br />

with 27gauge 5/8 inch needles<br />

• Epi-pen Auto-injectors 0.3mg<br />

<strong>for</strong> adults & 0.15mg <strong>for</strong> children<br />

• Alcohol pads<br />

• 2x2 gauze pads<br />

• Gloves<br />

• Sharps container<br />

• Crash cart – BLS+ level<br />

– Vital signs monitor, SO 2<br />

– Equipment to establish an<br />

oral airway<br />

– AMBU bag & oxygen<br />

equipment<br />

– Intravenous access/fluids<br />

– Injectable epinephrine<br />

– Injectable antihistamine<br />

– Injectable steroids<br />

• Phone (911)

So You Still Want to Give Shots?<br />

• What is needed?<br />

– Good communication between you and your Allergist<br />

• Precise instructions/protocols IAW ACAAI Practice Parameters<br />

• AIT/VIT Vials labeled IAW ACAAI Practice Parameters<br />

• Precise descriptions of reactions and <strong>the</strong>ir treatment<br />

– Facility<br />

• Refrigeration, supplies<br />

• Standard <strong>for</strong>ms<br />

• Equipment to manage anaphylaxis (ABCD’s)<br />

– Personnel<br />

• Trained to give shots, recognize and treat anaphylaxis<br />

• Staff BLS capable<br />

• Physician available within 2-3 minutes

What To Expect (Demand) from<br />

<strong>the</strong> Allergist<br />

• A record of previous responses to and compliance<br />

with <strong>the</strong> allergy shot program<br />

• Full, clear, and detailed documentation of <strong>the</strong><br />

patient’s immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy schedule<br />

• General instructions <strong>for</strong> administration of<br />

immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

• Recommendations <strong>for</strong> dose adjustment <strong>for</strong><br />

reactions & unexpected intervals between shots<br />

• Instructions on how to treat reactions to<br />

immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy injections<br />

Li JT, et. al., Allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy: A Practice Parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2003; 90(suppl).

Summary<br />

• <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> is an effective and potentially<br />

disease-modifying treatment <strong>for</strong> asthma, allergic<br />

rhinitis and stinging insect anaphylaxis.<br />

• Effectiveness of immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy depends on<br />

appropriate dose and duration of treatment.<br />

• Serious reactions to immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy are uncommon.<br />

• Appropriate safety measures based on known risk<br />

factors may prevent or reduce incidence of serious<br />

reactions.

Summary<br />

• Risk factors <strong>for</strong> adverse events during immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

administration include:<br />

– “A Momentary Lapse in Concentration”<br />

• Check and double-check<br />

– Right Patient (check ID)<br />

– Right Extract (extract contents / Rx number must be on vial)<br />

– Right Strength (extract cap color, written concentration)<br />

– Right Time (date of injection is within prescribed schedule)<br />

– Right Dose (have patient verify vial # and amount drawn)<br />

– Presence of symptomatic asthma<br />

• Do not administer allergy shot(s) until asthma is stable and PF ><br />

70% of personal best.

Summary<br />

• Risk factors <strong>for</strong> adverse events during immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

administration include:<br />

– Use of beta-blockers: ask about ALL new medications<br />

each visit<br />

– Injections from new vials: dosage adjustment per<br />

prescribing allergist – review previous schedules<br />

– High degree of shot sensitivity<br />

• Consider premedication<br />

• Consult prescribing allergist if recurrent and/or persistent large<br />

local reactions<br />

• Always consult allergist be<strong>for</strong>e fur<strong>the</strong>r administration if patient<br />

experienced a systemic reaction with <strong>the</strong> previous injection

End of Selection<br />

Go to Bookmarks &<br />

select ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

presentation or<br />

reference article

• Alcohol pads<br />

• 2x2 gauze pads<br />

• 1ml <strong>for</strong> (AIT) & 3ml <strong>for</strong> VIT<br />

disposable (safety) syringe<br />

with 27gauge 5/8’ needle<br />

• Aeroallergen or venom<br />

extract<br />

• Epinephrine autoinjector<br />

0.3mg <strong>for</strong> adults and<br />

0.15mg <strong>for</strong> children<br />

• Glucagon<br />

• Vital Signs monitor<br />

• Oxygen administration equipment<br />

• Crash cart<br />

• Gloves<br />

• Tourniquet<br />

• Sharps container<br />

<strong>Safety</strong> needles

• Allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy (allergy shot) is a <strong>for</strong>m of treatment<br />

aimed at decreasing sensitivity to substances called allergens.<br />

• Allergens are <strong>the</strong> substances that trigger your allergy<br />

symptoms when you are exposed to <strong>the</strong>m and are identified by<br />

allergy testing.<br />

• Allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy involves injecting increasing amounts<br />

of an allergen until a maintenance dose is reached and<br />

continued over 3 to 5 years.<br />

• <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> has been shown to decrease current<br />

symptoms, prevent <strong>the</strong> development of new allergies and, in<br />

some children, prevent <strong>the</strong> progression of <strong>the</strong> allergic rhinitis to<br />

asthma.<br />

• Allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy can result in long-lasting relief of<br />

allergy symptoms after treatment is stopped.

The 2 Phases of <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong><br />

Prior to immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy; provide patient with immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy education<br />

packet and review material with patient to his/her/guardian’s full<br />

understanding and satisfaction.<br />

Build-up phase:<br />

Involves receiving injections with increasing amounts of allergens.<br />

Frequency of injections during this phase generally ranges from 1 to<br />

2 times a week, though more rapid build-up schedules are sometimes<br />

used.<br />

The duration of this phase depends on <strong>the</strong> frequency of <strong>the</strong><br />

injections but generally ranges from 3 to 6 months.<br />

Maintenance phase:<br />

This phase begins when <strong>the</strong> effective <strong>the</strong>rapeutic dose is reached.<br />

The effective maintenance dose is different <strong>for</strong> each person,<br />

depending on <strong>the</strong>ir level of allergen sensitivity (how 'allergic <strong>the</strong>y are'<br />

to <strong>the</strong> allergens in <strong>the</strong>ir vaccine) and <strong>the</strong>ir response to <strong>the</strong><br />

immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy build-up phase.<br />

Once maintenance dose is reached, <strong>the</strong>re will be longer periods of<br />

time between immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy shots. The intervals between<br />

maintenance immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy injections generally ranges from every 2<br />

to every 4 weeks.

BEFORE EACH SHOT!!!<br />

• Screen patient’s current health and medication status.<br />

• Per<strong>for</strong>m <strong>the</strong>se safety checks:<br />

– Right Patient (positively confirm – photo ID, etc.)<br />

– Right Extract (extract contents, prescription #, & name must be<br />

on vial)<br />

– Right Strength / Color/ Concentration<br />

– Right Time (make sure date of injection is within prescribed<br />

schedule)<br />

– Right Dose (have patient verify vial # and amount drawn correct)<br />

* Patient verification of all <strong>the</strong> above.<br />

• All asthmatic patients receiving immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

must per<strong>for</strong>m peak flow measurements (three<br />

measurement attempts) with best reading meeting or<br />

exceeding set parameters, prior to injections!

Wipe injection site (<strong>the</strong> dorsal aspect of upper arm, halfway between elbow and<br />

shoulder).<br />

Wipe tops of extracts with alcohol, draw up extracts per protocol.<br />

With gloved hands, administer injections subcutaneously at a 90 0 angle with ½<br />

- 5/8 inch needles or 45 0 angle with 1 inch needle.<br />

Hold 2x2 on site firmly <strong>for</strong> a few seconds. Do not rub.<br />

Dispose of syringe and needle in <strong>the</strong> sharps container<br />

NEVER RE-CAP NEEDLES.<br />

Apply band aid/ice/ topical steroid cream, if needed.<br />

Instruct patient to remain in <strong>the</strong> waiting area <strong>for</strong> 30 minutes after <strong>the</strong> allergy<br />

injection and return to <strong>the</strong> treatment (injection) room to have area checked and<br />

documented prior to leaving <strong>the</strong> clinic.

instruct patient to report any abnormal signs and or symptoms <strong>the</strong>y<br />

may experience to staff immediately <strong>for</strong> appropriate medical<br />

intervention.<br />

After 30 minutes, feel <strong>the</strong> injection sites <strong>for</strong> any swelling (induration);<br />

also note any redness (ery<strong>the</strong>ma).<br />

Document any initial findings on AIT record per reactions<br />

instructions noted below.<br />

Document fur<strong>the</strong>r dose reduction instructions <strong>for</strong> future injections per<br />

physician’s orders on <strong>the</strong> SF-600 and on <strong>the</strong> treatment record,<br />

based on reactions.<br />

Instruct patient to notify staff of any delayed reactions after <strong>the</strong>y<br />

leave <strong>the</strong> clinic, prior to injections. Follow “Grading” delayed<br />

reactions dose reduction protocol below <strong>for</strong> injections.

Local reactions:<br />

• Are fairly common<br />

• Present as redness and<br />

swelling at <strong>the</strong> injection<br />

site.<br />

• Can happen immediately,<br />

or several hours after<br />

injections.<br />

Systemic reactions:<br />

• Less common.<br />

• Include increased allergy symptoms such<br />

as sneezing, nasal congestion or hives.<br />

• Can include swelling in <strong>the</strong> throat,<br />

wheezing or a sensation of tightness in <strong>the</strong><br />

chest, nausea, dizziness, fainting, and/or<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r severe systemic symptoms.<br />

• Systemic reactions require immediate<br />

treatment. See treatment <strong>for</strong> anaphylaxis.

• Negative (swelling up to 15mm; i.e., dime size) – progress<br />

according to schedule.<br />

• “A” (swelling 15-20 mm; i.e., dime to nickel size) – Follow<br />

Allergist’s written instructions (e.g., continue to advance).<br />

• “B” (swelling 20 – 25 mm; i.e., nickel to quarter size) – Follow<br />

Allergist’s written instructions (e.g., repeat last dose given)<br />

• “C” (swelling persisting more than 12 hours or over 25mm; i.e.,<br />

quarter size or larger) – Follow Allergist’s written instructions (e.g.,<br />

decrease dosage by 1 dose).<br />

• Systemic reactions (hives, sneezing, itching, asthma, difficulty breathing, or<br />

shock) – Immediate care/action, <strong>the</strong>n follow Allergist’s written instructions.<br />

• Generally, <strong>the</strong> subsequent allergen extract dose is reduced to 1/3 of <strong>the</strong> last<br />

dose that did not cause a reaction and repeated 3 times be<strong>for</strong>e advancing<br />

per schedule.<br />

• If <strong>the</strong> injections cause repeated reactions or are suspected of causing<br />

repeated delayed symptoms, or if reactions prevent progression of treatment,<br />

contact <strong>the</strong> Allergist <strong>for</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>r instructions.

• Apply hydrocortisone (topical steroid)<br />

• Apply ice to site<br />

• Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) to<br />

reduce swelling<br />

• Take oral antihistamine (Benadryl, Allegra, etc.)<br />

• Non-prescription pain-relievers (acetaminophen) to<br />

relieve pain

Epi-Pen Adult<br />

Epi-Pen JR<br />

TwinJect<br />

• Notify <strong>the</strong> physician!<br />

• May be controlled by immediately placing a tourniquet above<br />

<strong>the</strong> injection site<br />

• Giving up to 0.01 ml/kg of 1: 1000 epinephrine up to 0.50 ml<br />

every 10-20 minutes subcutaneously.<br />

• For <strong>the</strong> average adult, give 0.10ml of 1:1000 epinephrine<br />

subcutaneously in <strong>the</strong> injection site and 0.2ml of 1:1000<br />

epinephrine in <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r arm or inject 0.3mg EpiPen / TwinJect<br />

auto injector intramuscularly into <strong>the</strong> anterolateral aspect of <strong>the</strong><br />

thigh.<br />

• For children, administer 0.15mg EpiPen/TwinJect IM into <strong>the</strong><br />

thigh.

• Expiration Dates:<br />

– Vials 1-3 (Silver, Green, Blue) = 6 MONTHS FROM DATE OF<br />

RECONSTITUTION<br />

– Vials 4-5 (Gold, Red) = 1 YEAR FROM DATE OF RECONSTITUTION<br />

*Expiration dates on vials 1-4 (Silver-Gold) must not exceed<br />

expiration date on vial 5 (Red).<br />

• Vial is good <strong>for</strong> 6 months if concentration is < 1:1000 w/v<br />

• Vial is good <strong>for</strong> 1 year if concentration is ≥ 1:1000 w/v

How to dilute from available vials:<br />

• Example: To make vial #4 from vial #5:<br />

– Equipments needed –<br />

• 1cc syringe/needle<br />

• 9cc Sterile Albumin Saline vial (from WRAMC extract lab)<br />

– Draw up 1cc of extract from vial #5 and inject into a<br />

9cc Sterile Albumin Saline vial (extract diluent)<br />

– Mix well to make a 1:10 v/v dilution<br />

– Label <strong>the</strong> newly made vial #4 with <strong>the</strong> following:<br />

• Patient’s name & SSN<br />

• Prescription number<br />

• Extract contents (abbreviations)<br />

• New concentration & vial color (as will not have proper cap)<br />

• Expiration date

~Making 10-fold Dilutions~<br />

9cc<br />

• To 9 cc Sterile Albumin<br />

Saline vial- draw up 1.0cc<br />

of extract and inject into<br />

new vial.<br />

• To 4.5 cc Sterile Albumin<br />

Saline vial- draw up 0.5<br />

cc of extract and inject<br />

into new vial.<br />

• To 1.8 cc Sterile Albumin<br />

Saline vial- draw up 0.2<br />

cc of extract and inject<br />

into new vial.<br />

1.0cc<br />

0.5cc<br />

0.2cc<br />

4.5cc<br />

1.8cc

Vial v/v W/V AU/ML BAU/ML<br />

5<br />

Red<br />

4<br />

Gold<br />

3<br />

Blue<br />

2<br />

Green<br />

1<br />

Silver<br />

1:1<br />

1:10<br />

1:100<br />

1:1000<br />

1:10,000<br />

1:100 2000 7750<br />

1:1,000 200 775<br />

1:10,000 20 77.5<br />

1:100,000 2 7.75<br />

1:1,000,000 0.2 .775

Venom Extract Dilutions:<br />

(follow manufacturer’s dilution instruction <strong>for</strong> maintenance vial)<br />

**For fur<strong>the</strong>r VIT dilutions, follow same protocol <strong>for</strong> AIT dilutions above**<br />

Strength<br />

100mcg/ml or 300mcg/ml<br />

10mcg/ml or 30mcg/ml<br />

1mcg/ml or 3mcg/ml<br />

0.1mcg/ml or 0.3mcg/ml<br />

0.01mcg/ml or 0.03mcg/ml<br />

Expiration from date of dilution<br />

6 months (not to exceed<br />

manufacturer’s expiration date)<br />

30 days<br />

30 days<br />

14 days<br />

1 day (24 hours)<br />

0.001 mcg or 0.003mcg/ml 1 day (24 hours)

Summary<br />

• Pull <strong>the</strong> patient's allergy record.<br />

• Pull <strong>the</strong> patient's extract. Ensure that <strong>the</strong> right extract is pulled <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> right<br />

patient, that <strong>the</strong> vial content agrees with what is ordered.<br />

• Question <strong>the</strong> patient about any delayed local reaction or systemic symptoms.<br />

Make <strong>the</strong> appropriate adjustment in <strong>the</strong> dosage IAW protocol guidelines. If <strong>the</strong><br />

patient states he or she had a delayed systemic symptoms, record this on <strong>the</strong><br />

injection administration record and make a follow up appointment with <strong>the</strong><br />

Allergist <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> patient to be seen be<strong>for</strong>e proceeding with immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy.<br />

• Check dosage progression schedule <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> amount of extract to be given.<br />

Document <strong>the</strong> dosage in <strong>the</strong> appropriate column on <strong>the</strong> injection record. The<br />

technician who is administering immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy will initial <strong>the</strong> appropriate<br />

areas on <strong>the</strong> treatment record. Annotate <strong>the</strong> date and time of administration,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> injection site.<br />

• Gently shake <strong>the</strong> vial be<strong>for</strong>e using. Draw up <strong>the</strong> dosage required using 1cc or<br />

3cc syringe with a 26 - 27 gauge (5/8 – ½ inch) safety needle. Change <strong>the</strong><br />

needle prior to injection. Ensure that <strong>the</strong> pertinent in<strong>for</strong>mation is checked:<br />

confirm this in<strong>for</strong>mation with <strong>the</strong> patient.<br />

(1) Right patient<br />

(2) Right extract<br />

(3) Right dosage<br />

(4) Right interval<br />

(5) Right method or technique

Summary (cont.)<br />

• Administer <strong>the</strong> allergy injection. Give <strong>the</strong> injection subcutaneously into <strong>the</strong><br />

posterolateral surface of <strong>the</strong> middle third of <strong>the</strong> upper arm. Always pull back<br />

on <strong>the</strong> plunger be<strong>for</strong>e <strong>the</strong> allergy extract is administered; if blood returns,<br />

withdraw <strong>the</strong> needle and use <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r arm. Avoid massaging <strong>the</strong> injection<br />

site to lessen unduly rapid absorption of <strong>the</strong> allergen.<br />

• Instruct <strong>the</strong> patient to wait 30 minutes in <strong>the</strong> patient waiting area and to<br />

report any problems immediately.<br />

• Check <strong>the</strong> injection site(s) prior to <strong>the</strong> patient leaving <strong>the</strong> clinic.<br />

• Document all reactions in <strong>the</strong> patient's allergy record. Notify <strong>the</strong> Physician<br />

In Charge and <strong>the</strong> Allergist if <strong>the</strong>re are recurrent local reactions limiting<br />

advancement of <strong>the</strong> allergy shot or any systemic reactions or o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

problems.<br />

• Unless reactions dictate a change in dosage and/or <strong>the</strong> Allergist annotates<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rwise, <strong>the</strong> technician will always follow <strong>the</strong> prescribed schedule on <strong>the</strong><br />

Allergen Extract Prescription Form. Any questions will be directed to <strong>the</strong><br />

Allergist be<strong>for</strong>e administering a shot.<br />

• No patient will be permitted to administer <strong>the</strong>ir own injections. Only <strong>the</strong><br />

Allergist may determine if patient may receive <strong>the</strong>ir injections at ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

location. summation

End of Selection<br />

Go to Bookmarks &<br />

select ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

presentation or<br />

reference article

Optimizing <strong>the</strong> <strong>Safety</strong> of <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Administration Outside of <strong>the</strong><br />

Prescribing Allergist’s Office<br />

I. <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> overview:<br />

Definition: Allergen <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> is a treatment aimed at modifying <strong>the</strong> allergic<br />

disease through a series of injections of a mixture of aeroallergen<br />

extracts composed or clinically relevant allergens identified during <strong>the</strong> allergy evaluation<br />

1. <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> has been shown to be effective in multiple controlled studies <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> treatment of allergic rhinitis, asthma and stinging insect venom hypersensitivity<br />

2. Potential prophylactic treatment: may prevent <strong>the</strong> development of new allergies or<br />

progression from allergic rhinitis to asthma<br />

II. <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> potential mechanisms: Immunologic changes during<br />

immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy are complex. Successful immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy is often associated with a shift<br />

from TH2 to TH1 CD4 lymphocyte immune response to allergen. <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong><br />

induces a number of immunologic changes. Studies over several seasons of<br />

immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy show that <strong>the</strong> usual seasonal rise of IgE is blunted by immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy.<br />

On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, it is believed that IgG protective “blocking antibody” production is<br />

stimulated by immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy. However, <strong>the</strong>se changes in IgE and IgG may not<br />

correlate with clinical efficacy. <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> inhibits <strong>the</strong> early and late phase<br />

responses, which results in decreased inflammation. Partial desensitization may play a<br />

role in immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy. <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> may also induce production of “regulatory” T<br />

cells (CD4+CD25+) which may produce factors (IL-10and/or TGF-β) to down-regulate<br />

allergic immune responses. Clinically effective immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy may be <strong>the</strong> result of<br />

some or all of <strong>the</strong>se mechanisms.<br />

III. Indications and Contraindication <strong>for</strong> Allergen <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong><br />

1. Candidates: Patients with allergic rhinitis and/or asthma* with symptoms after<br />

natural exposure to aeroallergens and demonstrable evidence of clinically relevant<br />

specific IgE poor response to pharmaco<strong>the</strong>rapy and/or allergen avoidance and 1 of<br />

<strong>the</strong> following 1<br />

a. Unacceptable adverse effects of medications<br />

b. Desire to reduce or avoid long-term pharmaco<strong>the</strong>rapy and <strong>the</strong> cost of<br />

medication.<br />

c. Coexisting allergic rhinitis and asthma<br />

d. <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> may prevent <strong>the</strong> development of asthma in patients with<br />

allergic rhinitis<br />

e. <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> may prevent <strong>the</strong> development of new allergen sensitivities<br />

2. Patients who are not allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy candidates: Medical conditions<br />

that reduce <strong>the</strong> patient’s ability to survive a systemic reaction are relative<br />

contraindications <strong>for</strong> allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy. 1

a. Medical conditions that reduce <strong>the</strong> patient’s ability to survive a systemic<br />

reaction are relative contraindications <strong>for</strong> allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy such as<br />

severe coronary artery diseases<br />

b. Patients who are mentally or physically unable to communicate clearly with<br />

<strong>the</strong> allergist<br />

c. Patients who have a history of noncompliance<br />

d. Cautious attitude in prescribing immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy to patients on beta-blocker<br />

medications.<br />

e. Pregnancy (do not initiate <strong>the</strong>rapy in newly pregnant women but can<br />

continue in those already on immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy)<br />

IV: <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> protocol 2<br />

• Build-up phase: involves receiving injections with increasing amounts of<br />

<strong>the</strong> allergens. The frequency of injections during this phase generally ranges<br />

from 1 to 2 times a week, though more rapid build-up schedules are<br />

sometimes used. The duration of this phase depends on <strong>the</strong> frequency of <strong>the</strong><br />

injections but generally ranges from 3 to 6 months (at a frequency of 2 times<br />

and 1 time a week, respectively).<br />

• Maintenance phase: This phase begins when <strong>the</strong> effective <strong>the</strong>rapeutic<br />

dose is reached. The effective <strong>the</strong>rapeutic dose is based on<br />

recommendations from a national collaborative committee called <strong>the</strong> Joint<br />

Task Force <strong>for</strong> Practice Parameters: Allergen <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong>: A Practice<br />

Parameter 2003 and was determined after review of a number of published<br />

studies on immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy. The effective maintenance dose may be<br />

individualized <strong>for</strong> a particular person based on <strong>the</strong>ir degree of allergen<br />

sensitivity (how ‘allergic <strong>the</strong>y are’ to <strong>the</strong> allergens in <strong>the</strong>ir vaccine) and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

response to <strong>the</strong> immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy build-up phase. Once <strong>the</strong> maintenance dose<br />

is reached, <strong>the</strong> intervals between <strong>the</strong> allergy injections can be increased. The<br />

intervals between maintenance immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy injections generally ranges<br />

from every 2 to every 4 weeks but should be individualized to provide <strong>the</strong> best<br />

combination of effectiveness and safety <strong>for</strong> each person. Allergists may<br />

consider several factors in determining maintenance injection frequency<br />

including degree of symptomatic control at a particular maintenance interval<br />

and reactions from allergy injections. Shorter intervals between allergy<br />

injections may lead to less reactions and greater efficacy in some people.<br />

V. Allergen <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> <strong>Safety</strong>:<br />

1. Risk factors <strong>for</strong> allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy 3<br />

a. Error in dosage<br />

b. Presence of symptomatic asthma<br />

c. High degree of allergen hypersensitivity<br />

d. Use of beta-blockers<br />

e. Injections from new vials<br />

f. Injections given during periods when symptoms are exacerbated

2. Allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy local and systemic reactions<br />

a. Local reactions common<br />

b. Incidence of systemic reactions (SR) with conventional immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

schedules in <strong>the</strong> published literature <strong>for</strong> combined build-up and maintenance<br />

phase ranged from: 3 0.05% - 3.2 % per injection or 0.84% to 46.7% of<br />

patients (mean 12.92%, SD 10.8 % of pts) 4<br />

3. Treatment of <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Adverse Reactions<br />

a. Local reactions common occurrence: redness, swelling and heat at<br />

injection site<br />

i. If persistent large local reaction consider:<br />

1. Pre-medication with H1 blockers<br />

2. Decreasing dose or rate of build-up<br />

b. Systemic reactions: <strong>the</strong> recommendations <strong>for</strong> epinephrine administration<br />

are derived from <strong>the</strong> most recent practice parameters <strong>for</strong> treatment of<br />

anaphylaxis 9<br />

i. Epinephrine 1:1000 w/v<br />

1. Adults: 0.2 to 0.5ml intramuscularly (IM), preferably <strong>the</strong> thigh or<br />

subcutaneously (SQ) into <strong>the</strong> arm (deltoid) every 5 minutes, as needed<br />

to control symptoms and raise blood pressure<br />

2. Children: 0.01ml/kg (max 0.3 mg dosage) every 5 minutes as<br />

needed to, as needed to control symptoms and raise blood pressure<br />

3. Alternately, an epinephrine autoinjector (e.g., EpiPen or EpiPen<br />

Jr or TwinJect ) can be administered through clothing into <strong>the</strong><br />

lateral thigh.<br />

4. Do not use crash cart injectables in pre-filled syringe, which are<br />

1:10,000 wt/v and indicated <strong>for</strong> intravenous (IV) use<br />

5. Location of injection: arm permits easy access <strong>for</strong> administration of<br />

epinephrine, although intramuscular injection into <strong>the</strong> anterolateral<br />

thigh produces higher and more rapid peak plasma levels compared<br />

with IM or SQ injections in <strong>the</strong> arm. 9<br />

ii. O<strong>the</strong>r interventions:<br />

1. H1 antihistamines: diphenhydramine IM or IV<br />

a. Adults: 25 to 50 mg<br />

b. Children: 1-2 mg/kg<br />

2. H2 blockers p.o. or IV (cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine) – <strong>for</strong><br />

epinephrine – resistant hypotension<br />

3. Intravenous fluids or vasopressors as needed <strong>for</strong> vascular collapse<br />

4. Consider glucagon if patient on beta-blocker<br />

5. Maintain <strong>the</strong> airway<br />

iii. Call prescribing allergists <strong>for</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>r instructions be<strong>for</strong>e administering<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r allergy injection after a patient has had a systemic reactions<br />

4. Allergen <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Administration Supervision: appropriate<br />

setting, personnel and equipment.

Allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy should be given in settings where emergency<br />

resuscitative equipment and trained personnel are immediately available to treat<br />

systemic reactions under <strong>the</strong> supervision of a physician or licensed physician<br />

extender 6<br />

The trained personnel should be familiar with <strong>the</strong> following procedures:<br />

a. Adjustment of dose of allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy extract to minimize<br />

reactions.<br />

b. Recognition and treatment of local and systemic reactions to<br />

immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy injections.<br />

c. Basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation.<br />

d. Ongoing patient education in recognition and treatment of local and<br />

systemic reactions that occur outside <strong>the</strong> physician’s office.<br />

Equipment<br />

a. Stethoscope and sphygmomanometer.<br />

b. Tourniquet, syringes, hypodermic needles (14-gauge) and large bore<br />

needles.<br />

c. Aqueous epinephrine HCL 1:1000.<br />

d. Equipment to administer oxygen by mask.<br />

e. Intravenous fluid set-up.<br />

f. Antihistamine.<br />

g. Corticosteroids <strong>for</strong> intravenous injection.<br />

h. Vasopressor<br />

i. Oral airway.<br />

j. Equipment to maintain an airway appropriate <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> supervising physician<br />

expertise and skill.<br />

5. <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Administrations documentation: what you should receive<br />

and record<br />

A full, clear, and detailed documentation of <strong>the</strong> patient’s immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy schedule<br />

must accompany <strong>the</strong> patient when he or she transfers from one physician to<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r. Also, a record of previous responses to and compliance with <strong>the</strong> program<br />

should be communicated to <strong>the</strong> new physician. Finally, a detailed record of <strong>the</strong><br />

results of <strong>the</strong> patient’s specific- IgE antibody tests (immediate-type skin tests or in<br />

vitro tests) should be provided. 1<br />

6. Allergy Extract Nomenclature: Recommended Dilution Labeling, Color-<br />

Coding and Vial Nomenclature 1<br />

Un<strong>for</strong>tunately, <strong>the</strong>re is considerable diversity in <strong>the</strong> allergy extract nomenclature in<br />

US and this may lead to confusion and administration errors in outside offices<br />

particularly if <strong>the</strong>y supervise immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy from several offices with different<br />

nomenclature systems. The Joint Task Force On Practice Parameters developed

a proposed uni<strong>for</strong>m nomenclature system with <strong>the</strong> goal to have this system<br />

eventually adopted by all practicing US allergists. Number 1 vial is color coded red<br />

and called <strong>the</strong> 1:1 v/v dilution or maintenance concentrate. The subsequent dilutions<br />

are colored and named as below. However not all practices have adopted this<br />

standard nomenclature and <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e it is very important <strong>for</strong> you to review <strong>the</strong>,<br />

labeling nomenclature from each office that you receive allergy immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

vaccines.<br />

Dilution from<br />

maintenance<br />

Dilution designation<br />

in volume per volume<br />

(V/V)<br />

Number<br />

Color<br />

Maintenance 1:1 1 Red<br />

10-fold 1:10 2 Yellow<br />

100-fold 1:100 3 Blue<br />

1000-fold 1:1000 4 Green<br />

10,000-fold 1:10,000 5 Silver<br />

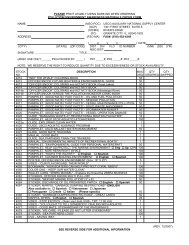

7. Administration Form In<strong>for</strong>mation:<br />

• Patient name, date of birth and telephone number<br />

• Prescribing physician with practice demographics<br />

• Vaccine name and dilution from maintenance in volume per volume, bottle<br />

letter, color and number (if used)<br />

• Expiration date of all dilutions<br />

• Date of injection<br />

• Arm injection administered<br />

• Delivered volume reported in milliliters<br />

• <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> schedules<br />

• Injection reactions: to be used to document local or systemic reactions<br />

• Health screen - Verbal or written interview of patient to evaluate patient’s health<br />

status prior to administering <strong>the</strong> allergy vaccine<br />

• Peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR); In patients with asthma (unstable asthma in<br />

particular), peak expiratory flow rate measurements should be obtained be<strong>for</strong>e<br />

each injection. If done repeatedly over time, this permits better determination of<br />

baseline peak expiratory flow rate and variability. PEFR variability, <strong>the</strong> difference<br />

in peak expiratory readings taken at different times, has a diurnal pattern with <strong>the</strong><br />

lowest reading usually in <strong>the</strong> morning. Normal PEFR variability is

patient’s peak expiratory flow rate is 20% below baseline, <strong>the</strong> clinical condition of<br />

<strong>the</strong> patient should be evaluated be<strong>for</strong>e administration of <strong>the</strong> injection.<br />

• Obtain peak flow measurement in asthmatic patients be<strong>for</strong>e<br />

administering<br />

• If 20 % below best baseline withhold allergy injection until fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

evaluation<br />

• Antihistamine use: Ask whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> patient has taken an antihistamine that<br />

day to improve consistency in interpretation of reactions:<br />

• May reduce adverse reactions: a concern with <strong>the</strong> use of<br />

premedication is that it may mask milder systemic reactions allowing <strong>the</strong><br />

build-up to proceed to a subsequent more serious systemic reaction. To<br />

<strong>the</strong> contrary, <strong>the</strong> published literature on studies utilized accelerated<br />

schedules <strong>for</strong> inhalant and venom allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy have<br />

demonstrated less incidence of local and systemic reactions with<br />

antihistamine premedication 6,7<br />

VI. Allergen <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Administration Supervision: practical tips to enhance<br />

safety<br />

1. Review all documents carefully<br />

2. Inspect <strong>the</strong> allergy vaccine vials and familiarize yourself with <strong>the</strong> nomenclature<br />

and dosing schedule<br />

3. Vials in transit should be not be exposed to temperature extremes (freezing or<br />

extreme heat) because this could decrease extract potency<br />

4. Storage of allergy vaccine vials: keep refrigerated at 4° .Prolonged exposure of<br />

allergy vaccine vials to room temperature over time may diminish extract<br />

potency: one study found loss of potency pollen extracts exposed to room<br />

temperature <strong>for</strong> 13 hours a week <strong>for</strong> longer than 3 months 8<br />

5. Do not administer injection unless you have written verification of <strong>the</strong> last<br />

injection dose and date<br />

6. Interview <strong>the</strong> patient about current health status including medication changes<br />

7. Have <strong>the</strong> patient wait in <strong>the</strong> office <strong>for</strong> 30 minutes after <strong>the</strong> injection and instruct<br />

<strong>the</strong>m to immediately report to <strong>the</strong> staff any symptoms suggestive of an allergic<br />

reaction.<br />

Do not hesitate to contact prescribing allergist if you have ANY questions or concerns!<br />

VII. Allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy adverse reactions: measures that can minimize <strong>the</strong><br />

risk:<br />

Serious reactions to immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy are uncommon. Appropriate safety measures<br />

based on <strong>the</strong> known risk factors may prevent or reduce incidence of serious reactions.

Risk factors <strong>for</strong> immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy and some measures that may help prevent<br />

include:<br />

1. Error in dosage: check and double-check: vials, patient name and dosing record,<br />

have patient confirm vials<br />

2. Presence of symptomatic asthma: do not administer injection until asthma<br />

stabilize<br />

3. High degree of hypersensitivity: consider premedication, consult prescribing<br />

allergists if recurrent and persistent large local reactions<br />

4. Use of beta-blockers: ask about new medications each visit<br />

5 Injections from new vials: dosage adjustment per prescribing allergist<br />

6. Injections made during periods of exacerbation of symptoms: consider consulting<br />

prescribing allergist be<strong>for</strong>e administering<br />

Remember: Take your time and review <strong>the</strong> records to ensure that:<br />

You are giving <strong>the</strong> right dose of <strong>the</strong> right allergy immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy vial to <strong>the</strong> right<br />

patient because….<br />

No patient ever died from an allergy shot waiting to receive <strong>the</strong> injection …<br />

The extra time and wait will not harm you or <strong>the</strong> patient but dosing errors and allergy<br />

injections to actively symptomatic patients may seriously harm<br />

References For Optimizing The <strong>Safety</strong> Of <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Administration Outside<br />

Of The Prescribing Allergist’s Office<br />

1. Li JT et al Joint Task Force On Practice Parameter: Allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy: A<br />

practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2003; 90(suppl).<br />

2. What are “Allergy Shots?” Tips to Remember are created by <strong>the</strong> Public Education<br />

Committee of <strong>the</strong> American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. This<br />

brochure was updated in 2003 available at AAAAI website (www.aaaai.org)<br />

http://www.aaaai.org/patients/publicedmat/tips/whatareallergyshots.stm<br />

3. Bousquet J., Lockey R., Malling H.J. WHO Position Paper Allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy:<br />

<strong>the</strong>rapeutic vaccines <strong>for</strong> allergic diseases Allergy Eur. J of Allergy Clin Immunol 1998;<br />

Number 44 Volume 53<br />

4. Stewart GE, Lockey, RE: Systemic reaction to Allergen <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong>, J Allergy and<br />

Clin Immunol 1992:90; 567-78.<br />

5. Position Statement on administration of immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy outside of <strong>the</strong> prescribing<br />

allergist facility. Drug and Anaphylaxis Committee of ACAAI. Ann Allergy Asthma and<br />

Immunol 1998;81:101-102<br />

6. Muller U, Hari Y, Berchtold E, Premedication with antihistamines may enhance<br />

efficacy of specific-allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;107 (1):81-<br />

861

7. Neilson L, Johnsen C, Mosbech H, Poulsen L, Malling H Antihistamine premedication<br />

in specific cluster immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy: A double-blind-placebo controlled study. J Allergy<br />

Clin Immunol 1996; 97 (6): 1207-13<br />

8. Nelson HS Effect of preservatives and conditions of storage on <strong>the</strong> potency of allergy<br />

extracts J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1981 Jan; 67(1):64-9<br />

9. Lieberman P et al The Diagnosis &Management of Anaphylaxis: An updated Practice<br />

J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 115 (3) (supplement)<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r suggested references:<br />

Efficacy<br />

a. Durham et al. Long-term Clinical Efficacy of Grass-pollen <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> New<br />

England Journal of Medicine 1999;341 468<br />

Possible preventive effect of allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

a. Des Roches A, Paradis L, Menardo J-L, et al. <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> With A Standardized<br />

Dermatophagoides Pteronyssinus Extract VI. Specific <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Prevents The<br />

Onset of New Sensitizations In Children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997; 99;450-3.<br />

b. Rurello-D'Ambrosio et al. Prevention of new sensitizations in monosensitized subjects<br />

submitted to specific immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy or not. A retrospective study. Clin Exp Allergy<br />

2001; 31: 1295-1302<br />

c. Panjno, GB et al. Prevention of new sensitization in asthmatic children monsensitized<br />

to house dust mites by specific immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy. A six-year follow-up study. Clin Exp<br />

Allergy 2001; 31:1392-7<br />

d. Jacobsen L Dreberg S, et al. <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> as a Preventive Treatment (Abstract) J<br />

Allergy Clin Immunol 1996;97: 232<br />

e. Polosa R, Al-Delaimy WK, Russo C, Piccillo G, Sarva M. Greater risk of incident<br />

asthma cases in adults with allergic rhinitis and effect of allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy: a<br />

retrospective cohort study. Respir Res 2005 6:153.<br />

Adverse reactions: treatment<br />

a. Simons F, Roberts J, Gu X, Simons K. Epinephrine absorption in children with a<br />

history of anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998; 33-34.<br />

b. The diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis: an updated practice parameter. J<br />

Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005 Mar;115 (3 Suppl 2):S483-523.<br />

Systemic Reactions and <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Fatalities<br />

a. Lockey RF, Benedict LM, Turkeltaub PC, and Bukantz SC J Allergy Clin Immunol<br />

1987; 79: 660-77<br />

b. Reid MJ, Lockey RF, Turkeltaub PC, Platts-Mills TAE. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1993;<br />

92: 6-15<br />

c. Bernstein D, et. al. Twelve-year survey of fatal reactions to allergen injections and<br />

skin testing: 1990-2001 J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113:1129-36.)

End of Selection<br />

Go to Bookmarks &<br />

select ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

presentation or<br />

reference article

Click <strong>the</strong> ⌧ next to <strong>the</strong> heading to<br />

view <strong>the</strong> administrative material.

Documentation of allergen immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

Documentation of In<strong>for</strong>med Consent<br />

In<strong>for</strong>med consent is a process by which a patient and physician discuss various aspects of a<br />

proposed treatment. A copy of <strong>the</strong> signed written consent <strong>for</strong>m and any entries pertaining to <strong>the</strong><br />

consenting process be<strong>for</strong>e <strong>the</strong> immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy was initiated is/are required. The consent process<br />

usually consists of a record of <strong>the</strong> following:<br />

● Treatment proposed and its alternatives<br />

● Benefits expected from <strong>the</strong> treatment<br />

● Risks, including a fair description of how frequently adverse outcomes (including<br />

death) occur<br />

● Anticipated duration of treatment<br />

● Office policies that affect treatment<br />

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Content Form<br />

The purpose of this <strong>for</strong>m is to define <strong>the</strong> contents of <strong>the</strong> vaccine in enough detail that it could be<br />

duplicated if necessary.<br />

This <strong>for</strong>m should include <strong>the</strong> following:<br />

● Appropriate patient identifiers, including name, social security number, and birth date<br />

● Vaccine contents, including common name or genus and species of individual<br />

allergens and a description of all mixtures<br />

● Prescription number (USACAEL)<br />

● Volume of individual components and final concentration of each<br />

● Type of diluent used (if any)<br />

● <strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> expiration date (<strong>for</strong> each vial)<br />

<strong>Immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy</strong> Vaccine Administration Form<br />

This <strong>for</strong>m should be used to document <strong>the</strong> administration of vaccine to a patient. Its design<br />

should be clear enough so that <strong>the</strong> person administering an injection is unlikely to make an error<br />

in administration. It also should permit documentation in enough detail to allow later<br />

determination of what was done. The <strong>for</strong>m should contain <strong>the</strong> following:<br />

● Appropriate patient identifiers, including name, social security number, and birth date.<br />

Placement of <strong>the</strong> patient’s picture on <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>m may be helpful, particularly when more<br />

than 1 patient has <strong>the</strong> same name. If 2 or more patients have <strong>the</strong> same name, that fact<br />

should be noted on <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>m as well, as should a means of distinguishing <strong>the</strong> 2<br />

individuals.<br />

● Name of <strong>the</strong> vaccine, including an indication of <strong>the</strong> dilution from <strong>the</strong> maintenance<br />

concentrate in volume per volume. O<strong>the</strong>r identifiers, such as cap color, number, or<br />

letter, may help to reduce <strong>the</strong> risk of an administration error.<br />

● Dates and times of vaccine injection<br />

● Volume of vaccine administered in milliliters (mL) with each injection. During <strong>the</strong><br />

buildup phase, <strong>the</strong> dose can be determined using a standard (provided) schedule.<br />

● Arm in which <strong>the</strong> injection was given (left or right). This may facilitate determination<br />

of which vaccine causes local reactions. Because local reactions do not correlate<br />

reliably with systemic reactions, <strong>the</strong> presence of an immediate local reaction may not<br />

be a useful way to determine which vaccine caused a systemic reaction. Although it is

a common practice to alternate <strong>the</strong> arm into which a particular vaccine is given, <strong>the</strong>re<br />

is no evidence that this is necessary.<br />

● In patients with asthma (unstable asthma in particular), peak expiratory flow rate<br />

measurements may be considered be<strong>for</strong>e an injection. If a patient’s peak expiratory<br />

flow rate is significantly below baseline, <strong>the</strong> clinical condition of <strong>the</strong> patient should be<br />

evaluated be<strong>for</strong>e administration of <strong>the</strong> injection.<br />

● Description of any reactions. Dose adjustments may be necessary if reactions are<br />

frequent or severe.<br />

● Details of any treatment given in response to a reaction should be documented in <strong>the</strong><br />

medical record and referenced on <strong>the</strong> administration <strong>for</strong>m.<br />

● Any adjustment from <strong>the</strong> standard schedule and <strong>the</strong> reason <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> adjustment (e.g.,<br />

missed appointments).<br />

● Clinical status of <strong>the</strong> patient be<strong>for</strong>e <strong>the</strong> injection. In general, patients who have high<br />

fever or any significant systemic illness should not receive an injection. It is desirable<br />

to document <strong>the</strong> patient’s clinical condition be<strong>for</strong>e each injection, particularly if <strong>the</strong><br />

patient is symptomatic.<br />

● Whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> patient has taken an antihistamine that day<br />

● Whe<strong>the</strong>r any new medication has been taken since <strong>the</strong> last immuno<strong>the</strong>rapy injection<br />

Labels <strong>for</strong> Vaccine Vials<br />

Each vial of vaccine should be labeled in a way that permits easy identification. Each label<br />

should include <strong>the</strong> following in<strong>for</strong>mation:<br />

● Appropriate patient identifiers, including patient name, prescription or social security<br />

number, or birth date<br />

● General description of <strong>the</strong> vaccine contents. Because of space limitations, it may be<br />

necessary to abbreviate <strong>the</strong> antigens. Possible abbreviations are as follows: tree, T;<br />

grass, G; bermuda, B; weeds, W; ragweed, R; mold, M; Alternaria, Alt;<br />

Cladosporium, Cla; Penicillium, Pcn; cat, C; dog, D; cockroach, Cr; dust mite, DM; D.<br />

farinae, Df; D. pteronyssinus, Dp; mixture, Mx. A full and detailed description of vial<br />

contents should be recorded on <strong>the</strong> prescription/content <strong>for</strong>m.<br />