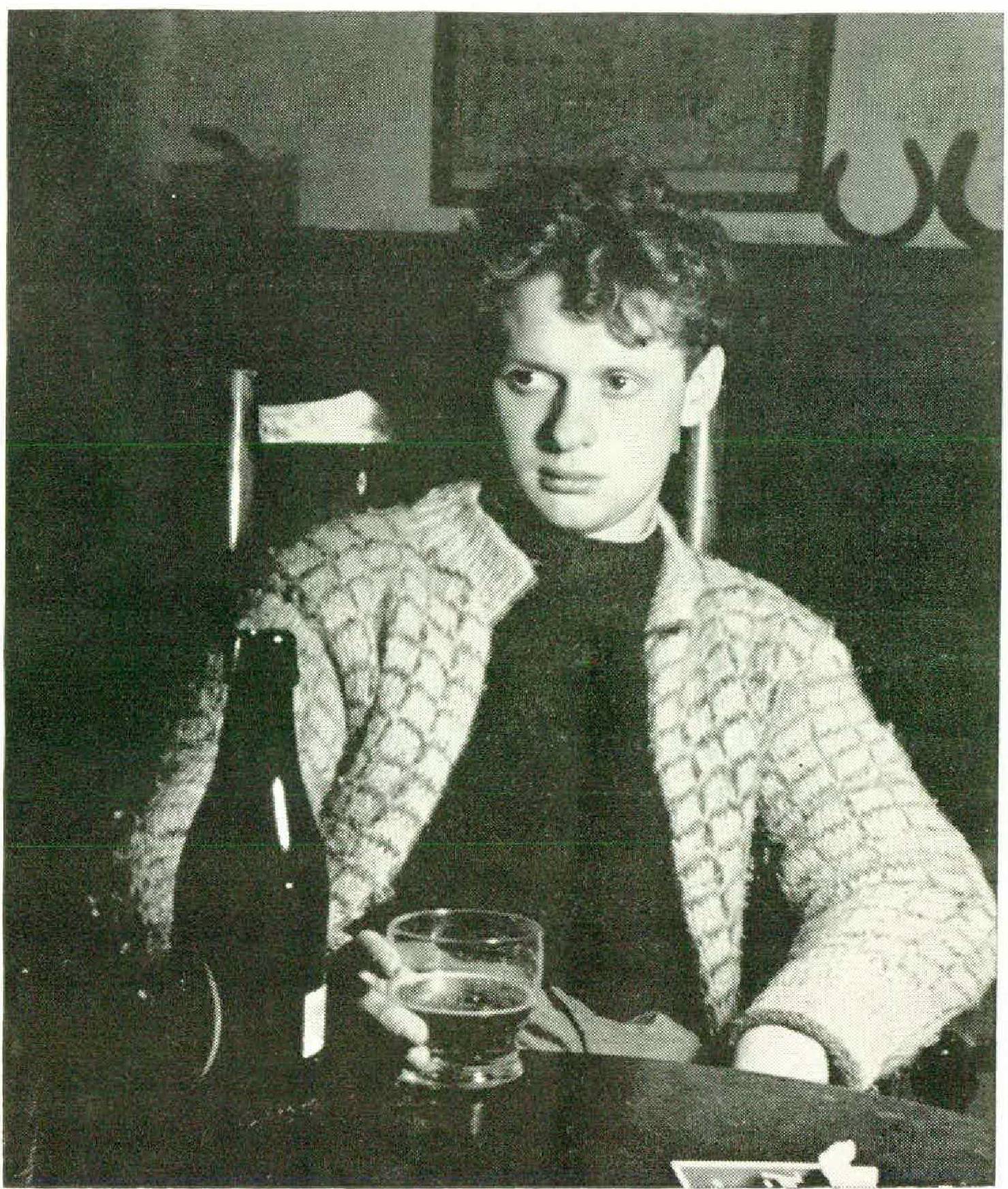

Young Dylan Thomas: The Poet in Love

Novelist and historian, and a friend of Dylan's, Constantine FitzGibbon was selected by the trustees of the Dylan Thomas estate to write his biography. In this second of two excerpts from THE LIFE OF DYLAN THOMAS,being published by Atlantic-Little, Brown, we see the young poet in his first venture in love, with the talented young writer Pamela Hansford Johnson.

by Constantine FitzGibbon

DYLAN THOMAS arrived at Battersea Rise, nervous and shy, on February 23, 1934, for a long weekend, straight from the train. As Pamela Hansford Johnson’s diary shows, she was already half in love with him, or at least prepared to fall in love, and she therefore remembered his arrival vividly, twenty years later, when she wrote in the Dylan Thomas Memorial number of Adam:

“He was nineteen, I was twenty-one. He arrived very late on a dull grey evening in spring, and he was nervous as I was. ‘It’s nice to meet you after all those letters. Have you seen the Gauguins?’ (He told me later that he had been preparing the remark about the Gauguins all the way from Swansea, and having made it, felt that his responsibility towards a cultural atmosphere was discharged.)

“He was very small and light. Under a raincoat with bulging pockets, one of which contained a quarter bottle of brandy, another a crumpled mass of poems and stories, he wore a grey, polo-necked sweater, and a pair of very small trousers that still looked much too big on him. He had the body of a boy of fourteen. When he took off the pork-pie hat (which, he also told me later, was what he had decided poets wore), he revealed a large and remarkable head, not shaggy — for he was visiting — but heavy with hair the dull gold of threepenny bits springing in deep waves and curls from a precise middle parting. His brow was very broad, not very high: his eyes, the colour and opacity of caramels when he was solemn, the colour and transparency of sherry when he was lively, were large and fine, the lower rims rather heavily pigmented. His nose was a blob; his thick lips had a chapped appearance; a fleck of cigarette paper was stuck to the lower one. His chin was small, and the disparity between the breadth of the lower and upper parts of his face gave an impression at the same time comic and beautiful. He looked like a brilliant, audacious child, and at once my family loved and fussed over him as if he were one.”

That first long weekend was, from her point of view, a success, as her diary shows. They went to the theater to see Sean O’Casey’s Within theGates; Victor Neuburg and Runia Tharpe came in one evening; but above all they talked, till one, till one fifteen, on one occasion till almost three. By day he visited editors and publishers, and he also traveled to the country to see his sister. But in the matter of his search for a job and for outlets for his work, the visit was not particularly successful. On Monday, March 5, he returned home. Her diary entry for that day reads:

Thought I’d have lunch with Dylan but he couldn’t manage it. Saw him after work — he’d sold 3 poems & 3 stories but had no job offers that suited him so after ½ an hour of supreme depression, I saw him off to Wales on the 5:55.

Three days later she received a letter from him telling her that he loved her, which took her by surprise.

Back in Swansea Dylan’s life seemed, at first, to continue exactly as before. Round and round in his head went the problem of how he could escape from Swansea; since his literary talents had failed to find him a job in London, he contemplated becoming a professional actor with the Coventry Repertory Company.

AN INFLUENTIAL poet had been reading Dylan’s poems, and he now wrote to him. This was Stephen Spender, who also spoke of him to Geoffrey Grigson and to T. S. Eliot, with the result that Dylan once again sent poems to New Verse and to The Criterion. Spender did more; he said that he would try to get Dylan some reviewing to do, so that he might earn a little money, for Dylan had written to him: “The fact that I am unemployed helps ... to add to my natural hatred of Wales.”

Dylan was, in fact, beginning to be known. The circle that then knew his name might be a very small one indeed, but in the world of poetry it was the most important. And the publicity of a minor scandal helped.

The poem which the Listener published on March 14 was “Light breaks where no sun shines,” a poem about conception. The first two lines of the second stanza are:

Warms youth and seed and burns the seeds of age.

The Listener was and is the literary organ of the BBC, and the BBC at that time was directed by Sir John Reith, now Lord Reith, who approached his duties in the highest spirit of Scottish Calvinist morality. The purity, not to say the Puritanism, of the BBC’s programs was a byword, and in certain emancipated circles, a laughingstock. And now letters began to arrive at the Corporation’s enormous office complaining that the BBC had published an obscene poem.

They caused consternation among the BBC’s many bureaucrats. A public apology was made. Furthermore, it seems that a ukase was issued; Dylan Thomas was temporarily blacklisted, and well over six months passed before another poem of his was published by the Listener.

(I must add that I have been unable to obtain any documentary confirmation of this, but I believe it to have been the case. And for the next ten years and more the BBC showed a marked reluctance to employ Dylan for programs audible in England. He did do a little work for the BBC before the war, and during the war he broadcast for the Overseas Service, but it was only when friends of his back from the war, such as Roy Campbell and John Arlott, obtained jobs as BBC producers that his very great talents on the air began to be used at all regularly. Since his death, the BBC has claimed him as its favorite and most favored protégé, but it was by no means always so.)

Nothing endears a writer to English highbrows more than a charge of obscenity. Inasmuch as this charge, or the complementary one of blasphemy, has been leveled by the philistines at almost every writer of genius since Hardy’s time and before, it is hardly surprising that many intellectuals have come to see a causal connection. The silly little fuss in the BBC did Dylan much good.

An event even more important for his future as a poet took place during this month of March. It was decided that he would be awarded the second major “Poets’ Corner” prize, which meant the publication of a volume of his poems, the costs being covered in part by The Sunday Referee. When it is realized how extremely hard it is for a poet to find a publisher willing to risk an almost certain loss on a first volume of poems, the value of this prize becomes apparent. It must have been personally gratifying, too, for him to have caught up, as it were, with Pamela Hansford Johnson, the only other prizewinner to date. On March 25, Palm Sunday, it was announced in The Sunday Referee that the prize had been given to Dylan.

But first Mark Goulden wished to see the young poet. Indeed, he has told me that so great was the virtuosity revealed in these poems that he could not help doubting whether this very young Welsh boy had in fact written them. In order to be sure that he was not the victim of a hoax he arranged to pay Dylan’s fare to London, and put him up for the night at the Strand Palace Hotel. This was probably Good Friday, and since the staff of a Sunday paper would be working on Saturday, it is most likely on that day that the confrontation took place. It was, Mr. Goulden has told me, almost an interrogation, with himself, his literary editor. Hayter Preston, and Victor Neuburg on one side of the table, Dylan on the other.

Dylan was extremely shy, as anyone in those circumstances might well be, but he quite quickly convinced Mr. Goulden that he was the author of the poems. When Goulden asked him how he wrote such remarkable poetry, he replied: “It just flows.”

The editor was satisfied, the award confirmed. Mr. Goulden believes that a check was handed over, though I suspect that this may be an error of memory. If there was a check, it was certainly a very small one. And then Dylan went off to spend Easter with Pamela and her mother.

It must have been a very happy Easter, too. Nothing is sweeter to a writer than recognition, and none so sweet as the first. He still had no job and no idea of how he would live when at last he should have succeeded in escaping from Swansea and his childhood. But at the age of nineteen such problems are relatively unimportant compared to the knowledge that a book of one’s own poems is to be published within the year. It is not hard to guess how he felt in the big red bus that carried him through Chelsea toward Battersea and his girl and, he must surely have thought, fame.

AFTER winning The Sunday Referee prize, he returned home on April 9 and set about preparing a volume of poems for publication. These poems came out of his old notebooks — though they were not old in those days — and he usually worked them over and partly or totally rewrote them, always in the direction of greater density and complexity. This meant putting aside a novel he had begun — “my novel about the Jarvis valley" — which was in fact a series of loosely connected stories, macabre and somber, with a Welsh rural setting.

He was lonely in Swansea, and he missed Pamela. On April 15 he wrote to her:

“I read over what I wrote this morning. All is silly, but why should I cross it out or throw it away. It’s just a little more me for you to grapple with. Which sounds even more conceited than many of the other things I’ve put in my letters to you. I’ve often wondered — I thought of asking you, but am always so vastly happy with you that I don’t like intruding morbid and egotistic subjects — whether you think me as conceited a little young man as I often think you must do. I’m not really; profoundly the other way. But I’ve noticed that when, for example, you — quite honestly and often misguidedly — run down your poetry, I never retaliate, as every true-blue poet should, by saying how very unsuccessful my own poetry is, too. I never say it, but not because I don’t think it. I know it. And when you say, of a poem of mine, ‘That’s bad,’ and I try to argue and show you how good it really is — that, too, must sound conceit. Darling, it isn’t. I’d hate you to think that I was at all self-contented, self-centred, self-satisfied in regard to — well, only one little thing, the things I write. Because I’m not. And not half as brave, dogmatic and collected in the company of literary persons as I might have led you to believe.”

It was almost certainly due to her wholesome influence that he was trying at this time to give up smoking, to drink only in moderation, and generally to improve his health. On the twenty-fifth of April he wrote to her:

“No, I haven’t been doing anything I shouldn’t. I have smoked only two cigarettes since I last saw you. You can’t — yes you can — realize how terrible it has been to give them up. I’ve chainsmoked for nearly five years; which must have done me a lot of good. I am allowed a pipe — mild tobacco, not too much. That keeps me alive, though I hate it like hell. I take walks in the morning and pretend there’s a sun in these disappointed skies. I even go without a coat (sometimes) in this cold weather, and tread bejumpered over the sheepy fields. ... I like to be tidyminded, but I so rarely am. Now the threads of half-remembered ideas, the fragments of halfremembered facts, blow about my head. I can write today only awkwardly and uneasily, nib akimbo. And I want to write so differently: in glowing, unaffected prose: with all the heat of my heart, or, if that is cold, with all the clear intellectual heat of the head. . . . And now I shall rise from the lovely fire, jam my hat hard and painfully on my head, and go out into the grey day. I am strong, strong as a circus horse. I am going to walk, alone and stern, over the miles of grey hills at the top of this my hill. I shall call at a public house and drink beer with Welshspeaking labourers. Then I shall walk back over the hills again, alone and stern, covering up a devastating melancholy and a tugging, tugging weakness with a look of fierce and even Outpost-of-the-Empire determination and a seven league stride. Strength! (And I’m damned if I want to go out at all. I want to play dischords on the piano, write silly letters or sillier verses, sit down under the piano and cry Jesus to the mice.)”

In his letters to her at this time he wrote at very great length about the poems and stories she was sending him. Her volume of poems, Symphony for Full Orchestra, was published, and he rejoiced with her at the good reviews it received, sympathized or was angry when the critics were less kind. He wrote surprisingly little about his own work, though in May he reported on the progress of his book.

“The old, fertile days are gone, and now a poem is the hardest and most thankless act of creation. I have written a poem since my last letter, but it is so entirely obscure that I dare not let it out even unto the eyes of such a kind and commiserating world as yours. I am getting more obscure day by day. It gives me now a physical pain to write poetry. I feel all my muscles contract as I try to drag out, from the whirlpooling words around my everlasting ideas of the importance of death on the living, some connected words that will explain how the starry system of the dead is seen, ordered as in the grave’s sky, along the orbit of a foot or a flower. But when the words do come, I pick them so thoroughly of their live associations that only the death in the words remains. And I could scream, with real, physical pain, when a line of mine is seen naked on paper and seen to be as meaningless as a Sanskrit limerick. I shall never be understood. I think I shall send no more poetry away, but write stories alone. All day yesterday I was working, as hard as a navvy, on six lines of a poem. I finished them, but had, in the labour of them, picked and cleaned them so much that nothing but their barbaric sounds remained. Or if I did write a line, ‘My dead upon the orbit of a rose,’ I saw that ‘dead’ did not mean ‘dead,’ ‘orbit’ not ‘orbit’ and ‘rose’ most certainly not ‘rose.’ Even ‘upon’ was a syllable too many, lengthened for the inhibited reason of rhythm. My lines, all my lines, are of the tenth intensity. They are not the words that express what I want to express; they are the only words I can find that come near to expressing a half. And that’s no good. I’m a freak user of words, not a poet. That’s really the truth. No self-pity there. A freak user of words, not a poet. That’s terribly true.”

There are passages even in Dylan’s earliest letters that are disingenuous or intended to surprise, but this one seems to me a true cri du coeur, and a very revealing one indeed. What he was trying to express in his poems was a view of the world for which the English language failed to provide the words, let alone the syntax. Yet he was determined to achieve the near-impossible, and he forced himself as he forced the words. At the same time, James Joyce was doing much the same with the work in progress that became Finnegans Wake. For both it was grinding, lonely work, with hopelessness never far away. And at the end of the day, a few lines written, what then?

THE picture that emerges from the letters he was then writing to Pamela Hansford Johnson is of a young poet working extremely hard and trying to improve his health by not drinking or smoking too much. He was, of course, writing to a girl on whom he was most anxious to make a good impression and who was, as he knew, not at all impressed by his “poetical” ame damnée pose, of which, indeed, he was himself beginning to weary.

“I am spending Whitsun in the strangest town in Wales. Laugharne, with a population of four hundred, has a townhall, a castle, and a portreeve. The people speak with a broad English accent, although on all sides they are surrounded by hundreds of miles of Welsh country. The neutral sea lies at the foot of the town, and Richard Hughes writes his cosmopolitan stories in the castle.

“I am staying with Glyn Gower Jones. ... He is a nice, handsome young man with no vices. He neither smokes, drinks, nor whores. He looks very nastily at me down his aristocratic nose if I have more than one guinness at lunch, and is very suspicious when I go out by myself. I believe he thinks I sit on Mr. Hughes’s castle walls with a bottle of rye whisky, or revel in the sweet confusion of a broad-flanked fisherwoman. ... I seem always to be complaining that I cannot fit the mood of my letters into the mood of the weathered world that surrounds me. Today I complain again for a hell-mouthed mist is blowing over the Laugharne ferry, and the clouds lie over the chiming sky — what a conceit — like the dustsheets over a piano. Let me, o oracle in the lead of the pencil, drop this customary clowning, and sprinkle some sweetheart words over the paper (paper torn slyly from an exercise book of the landlady’s small daughter). Wishes, always wishes. Never a fulfilment of action, flesh. The consummation of dreams is a poor substitute for the breathlessness at the end of the proper windy gallop, bedriding, musical flight into the Welsh heavens after a little, discordant brooding over the national dungtip.

“My novel of the Jarvis valley is slower than ever. I have already scrapped two chapters of it. It is as ambitious as the Divine Comedy, with a chorus of deadly sins, anagramatized as old gentlemen, with the incarnated figures of Love and Death, an Ulyssean page of thought from the minds of the two anagramatical spinsters, Miss P. and Miss R. Sion-Rees, an Immaculate Conception, a baldheaded girl, a celestial tramp, a mock Christ, and the Holy Ghost.

“I am a Symbol Simon. My book will be full of footlights and Stylites, and puns as bad as that, kiss me Hardy? Dewy love me? Tranter a body ask? I’ll Laugharne this bloody place for beingwet. I’ll pun so frequently and so ferociously that the rain will spring backwards on an ambiguous impulse, and the sun leap out to light the cracks of this sow world. But I won’t tell you my puns, for they run over reason, and I want you to think of me today not as a bewildered little boy writing an idiot letter on the muddy edge of a ferry, watching the birds and wondering which among them is the ‘sinister necked’ wild duck and which the terrible cormorant, but as a strong-shouldered fellow polluting the air with the smell of his eightpenny tobacco and his Harris tweeds, striding, golf-footed, over the hills and singing as loudly as Beachcomber in a world rid of Prodnose. There he goes, that imaginary figure, over the blowing mountains where the goats all look like Ramsay MacDonald, down the crags and the rat-hiding holes in the sides of the hill, on to the mud flats that go on for miles in the direction of the sea. There he stops for a loud and jocular pint, tickles the serving wench where serving wenches are always tickled, laughs with the landlord at the boatman’s wit (‘The wind be a rare one, he be. He blows up the petticoats of they visiting ladies for the likes of me. And a rare thirst he give you. Pray fill the flowing bowl, landlord, with another many magnums of your delectable liquor. Aye, aye, sor.’ And so on), and hurries on, still singing, into the mouth of the coming darkness. . . .

“I wish I could describe what I am looking on. But no words could tell you what a hopeless, fallen angel of a day it is. In the very far distance, near the line of the sky, three women and a man are gathering cockles. The oyster-catchers are protesting in hundreds around them. Quite near me, too, a crowd of silent women are scraping the damp, grey sand with the torn-off handles of jugs, and cleaning the cockles in the little drab pools of water that stare up out of the weeds and long for the sun. But you see that I am making it a literary day again. I can never do justice to the miles and miles and miles of mud and grey sand, to the unnerving silence of the fisherwomen, and the meansouled cries of the gulls and the herons, to the shapes of the fisherwomen’s breasts that droop, big as barrels, over the stained tops of their overalls as they bend over the sand, to the cows in the fields that lie north of the sea, and to the near breaking of the heart as the sun comes out for a minute from its cloud and lights up the ragged sails of a fisherman’s boat. These things look ordinary enough on paper. One sees them as shapeless, literary things, and the sea is a sea of words, and the little fishing boat lies still on a tenth rate canvas. I can’t give actuality to these things. Yet they are as alive as I. Each muscle in the cocklers’ legs is as big as a hill, and each crude footstep in the wretchedly tinted sand is deep as hell. These women are sweating the oil of life out of the pores of their stupid bodies, and sweating away what brains they had so that their children might eat. . . .

“Oh hell to the wind as it blows these pages about. I have no Rimbaud for a book or a paper rest, but only a neat, brown rock. . . . It’s getting cold, too cold to write. I haven’t got a vest on, and the wind is blowing around the Bristol Channel. I agree with Buddha that the essence of life is evil. Apart from not being born at all, it is best to die young. I agree with Schopenhauer (he, in his philosophic dust, would turn with pleasure at my agreement) that life has no pattern and no purpose, but that a twisted vein of evil, like the poison in a drinker’s glass, coils up from the pit to the top of the hemlocked world. Or at least I might do. But some things there are that are better than others. The tiny, scarlet ants that crawl from the holes in the rock on to my busy hand. The shapes of the rocks, carved in chaos by a tiddly sea. The three broken masts, like three nails in the breast of a wooden Messiah, that stick up in the far distance from a stranded ship. The voice of a snotty-nosed child sitting in a pool and putting shellfish in her drawers. The hundreds and hundreds of rabbits I saw last night as I lay incorrigibly romantic in a field of buttercups and wrote of death. The jawbone of a sheep that I wish would fit into my pocket. The tiny lives that go slowly and languidly on in the cold pools near my hand. The brown worms in beer. All these, like Rupert Brooke, I love because they remind me of you. Yes, even the red ants, the dead jawbone and the hapless chemical. Even the rabbits, buttercups, and nailing masts. Soon I see you. Write by the end of this week. Darling, I love you. xx”

WAS it overwork, boredom, frustration of every sort, loneliness, or a combination of these and perhaps of other, darker forces that had led him into this frame of mind? His reaction in the days that followed was characteristic of him, and by no means unknown in others when in such a frame of mind. His next letter to Pamela Hansford Johnson is not written in his usual small, neat hand with the letters sloping backward — the hand that so closely resembled Emily Brontë’s that when Lawrence Durrell, noticing the resemblance, sent him a photograph of a manuscript poem of hers, Dylan at first glance thought it was a manuscript of his, returned by a magazine. No, the next letter is a most untidy scrawl, the lines wandering up and down, the product of a hand as shaky as the heart was distraught. It is dated only Cwmdonkin Drive, Sunday morning, bed. I take it to have been written and posted on May 27, and there is corroboration for this in her diary entry for May 28, which reads: “Appallingly distressing letter from Dylan. I cried lustily nearly all day and had to write telling him it must finish. So an end to that affair.” This is the letter he had written to her:

“Question One. I can’t come up.

Two. I’m sleeping no better.

Three. No, I’ve done everything that’s wrong.

Four. I daren’t see the doctor.

Five. Yes, I love you.

I’m in a dreadful mess now. I can hardly hold the pencil or hold the paper. This has been coming for weeks. And the last four days have completed it. I’m absolutely at the point of breaking now. You remember how I was when I said goodbye to you for the first time. In the Kardomah when I loved you so much and was too shy to tell you. Well imagine me one hundred times worse than that with my nerves oh darling absolutely at the point of breaking into little bits. I can’t think and I don’t know what I’m doing. When I speak I don’t know if I’m shouting or whispering and that’s a terrible sign. It’s all nerves and more. But I’ve never imagined anything as bad.

“And it’s all my own fault too. As well as I can I’ll tell you the honest honest truth. I never want to lie to you. You’ll be terribly angry with me I know and you’ll never write to me again perhaps. But darling you want me to tell you the truth, don’t you. I left Laugharne on Wednesday morning and went down to a bungalow in Gower. I drank a lot in Laugharne and was feeling a bit grim even then. I stayed in Gower with ——, who was a friend of mine in the waster days of the reporter’s office. On Wednesday evening —— his fiancée came down. And she was tall and thin and dark and a loose red mouth and later we all went out and got drunk. She tried to make love to me all the way home. I told her to shut up because she was drunk. When we got back she still tried to make love to me, wildly like an idiot in front of ——. She went to bed and —— and I drank some more and then very modernly he decided to go and sleep with her. But as soon as he got into bed with her she screamed and ran into mine. I slept with her that night and for the next three nights. We were terribly drunk day and night. Now I can see all sorts of things. I think I’ve got them.

“Oh darling it hurts me to tell you this but I’ve got to tell you because I always want to tell you the truth about me. And I never want to share. It’s you and me or nobody, you and me and nobody. But I have been a bloody fool and I’m going to bed for a week. I’m just on the borders of DTs darling and I’ve wasted some of my tremendous love for you on a lank redmouthed girl with a reputation like a hell. I don’t love her a bit. I love you Pamela always and always. But she’s a pain on the nerves. For Christ knows why she loves me. Yesterday morning she gave her ring back to ——. I’ve got to put a hundred miles between her and me. I must leave Wales forever and never see her. I see bits of you in her all the time and tack on to those bits. I’ve got to be drunk to tack on to them. I love you Pamela and must have you. As soon as all this is over I’m coming straight up. If you’ll let me. No, but better or worse I’ll come up next week if you’ll have me. Don’t be too cross or too angry. What the hell am I to do? And what the hell are you going to say to me? Darling I love you and think of you all the time. Write by return. And don’t break my heart by telling me I mustn’t come up to London to you because I’m such a bloody fool.

“xxxx Darling. Darling oh.”

I have quoted this correspondence at such length, and this tragic letter in full save for omitting the names of the man and his fiancée, because they are intensely revealing to anyone who would understand the life and the death of Dylan Thomas.

Its first and most immediate effect was upon his relations with Pamela Hansford Johnson. Although she soon and generously forgave him, she was henceforth more cautious and, understandably enough, far more reluctant to commit herself and her love to a young man who could write to her in this fashion. It is, of course, possible that he was anxious to bring their relationship to a climax of one sort or another; that he unconsciously wished to be free of her or that he thought to force her into bed with him by showing her that if she would not come, there were others who would. But neither interpretation seems to me to be consistent either with Dylan’s character or with the tone of the letters. I believe he said exactly what he meant, and that what he meant was a cry for help.

Pamela has assured me that “darling” was definitely not amused. Few young women would be, in the circumstances. That she forgave him, though with reservations, within a very few days is proof not only of her affection for him but also of her young self-assurance.

Augustus John, who first met him a year or so later, has written: “The truth is that Dylan was at the core a typical Welsh Puritan and Non-conformist gone wrong.” This facile judgment contains its element of truth. Just as his father’s “atheism” was in fact a sort of God-hatred, so the son’s defiance of conventional morality implied, in its intensity, an acceptance of that morality in its crudest manifestations. Dylan expressed more than once his astonishment, even his admiration, that Augustus John could commit his multiple adulteries and whatnot without a twinge of conscience, could be drunk at night and remorseless in the morning. Dylan might be amoral about money and possessions, but not about sex and drink. He suffered, as this letter shows, paroxysms of guilt, and was to do so all his life. Caitlin Thomas, who should know if anyone does, wrote in Leftover Life to Kill: “Though Dylan imagined himself to be completely emancipated from his family background, there was a very strong puritanical streak in him, that his friends never suspected; but of which I got the disapproving benefit.”

Dylan soon recovered from his red-lipped remorse, and apparently from his fear of DT’s, too. Pamela was expecting him in London on June 5, but he was a week late, perhaps because he was getting his health back or perhaps because he was not at all sure of the reception he could expect in Battersea. On the sixth, though, she “wrote to the darling old fishface forgiving him,” and on the next day he wrote to Trevor Hughes, who was also a bachelor: “I am looking forward to the day when Mr. and Mrs. Hughes in their two-backed beast face the double-faced world. That way, perhaps, lies your salvation and mine, though I doubt whether I, personally, could remain sober and faithful for more than a week on end.”

This oblique and unpromising reference to matrimony was not purely theoretical. Almost as soon as he got to London in the following week he proposed to Pamela. Her diary entry for June 14 reads: “Met darling Dylan after work and we had a coffee. Met his friend Trevor Hughes and had a drink in Denman Street and at the Fitzroy. D. and I got home about 8.15. Had lovely evening — D. pressing me to marry him but I won’t — yet.” Nevertheless, as her diary shows, it was a very happy week for them both: “evening too happy for words,” “a lovely, lovely evening sitting in the garden of the Six Bells, arguing, laughing.” In her eyes they were, almost, a conventionally engaged couple.

But she had not committed herself, for she was worried. She was very young, and he was even younger, though this she did not then know, for he had added a couple of years to his nineteen in order to appear older than she. Sweet, enchanting, and amusing as he was, his pose as a wild boy confused and at times distressed her. She has told me that on one occasion when they had spent the evening over a couple of glasses of beer in the garden at the back of the Six Bells, Dylan met someone he knew on the way out and pretended to be drunk. Even a girl of her acute intelligence and possessing, as her novels show, a perspicacity for psychology far above the average, could hardly be expected to understand the extremely complex motivation behind such behavior. She was, quite simply, worried about Dylan and drink. And on June 22 she confided to her diary that she and Trevor Hughes “came to a very definite understanding re forming a watch committee over Dylan.”

There were to be many such watch committees in the years to come, almost always the creation of a woman who was, or thought she was, in love with Dylan. And there was no more certain way of arousing his alarm and, ultimately, his hostility. He always wanted women to look after him when he was ill, or in trouble, but not to prevent him from making himself ill or getting into trouble. Such had been the childhood pattern. And since drink was to him, among other things, a means of self-defense, he could only interpret the good ladies’ efforts to stop his drinking as a dangerous attack upon his freedom; and he valued his freedom above all things, for without freedom there would be no poems. Caitlin never made this mistake, which was why she was, and remained, the only woman he ever really loved. Once Pamela set about “reforming” him, their relationship was doomed. Yet who can blame her? For her, marriage to an unreformed Dylan, to Caitlin’s Dylan, would have been an impossibility. She loved him, and she tried, and throughout that summer of 1934 she thought that perhaps she might succeed. But her doubts increased.

During this summer and autumn his reputation as a poet grew as more and more of his poems were published in New Verse, the Criterion, the Adelphi, and elsewhere. He was selling his short stories, too. Throughout the whole of August and the first half of September, Dylan was staying with Pamela and her mother in Battersea. Her diary echoes the love and affection she felt for him, but there are some ominous entries. On several occasions he came in very late and the worse for drink; the next day she would be angry with him. And one can assume that living in the same house, he found the platonic nature of their love affair an increasing strain. Nevertheless, she continued to regard herself as his girl, if not his fiancee. He took her down to meet his sister, and she noted in her diary that she thought she had made a good impression. And then, on September 15, Pamela, her mother, and Dylan all went down to Swansea for two weeks, to meet his mother.

The visit, had it been successful, might perhaps have resulted in marriage, but it was not. In the first place the weather was appalling, and though they did their best to appreciate the beauties of the Gower Peninsula, they were usually confined to the cinema, hotel lounges, and No. 5 Cwmdonkin Drive. Then Mrs. Johnson found Mrs. Thomas, “who gabbled all day till we nearly went frantic,” increasingly tedious and irritating. They discovered, too, that Dylan was only nineteen. And toward the end of the visit, Pamela had a nervous collapse, so that a doctor had to be called in. Four days later the two women returned, sadly, to London. There had been no rupture with Dylan, no quarrel, but Pamela now realized that there could be no question of her marrying Dylan for a long, long time, if ever.