Gerry Sweet takes a nostalgic look at the Vickers VC10, the last long-haul airliner built solely by the British aircraft industry, as the type celebrates the 60th anniversary of its maiden flight.

The Vickers VC10 was not only the last large airliner to be built by an independent British aircraft manufacturer but, sadly, was also the last in the line of commercial aircraft built solely by Vickers that included the Varsity, Viking, Vanguard and Viscount.

During its relatively short commercial service life its graceful lines and comfortable cabin were appreciated by passengers and crews alike. But its disappointing sales record reflected the attitude of the then national flag carrier, British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), which had a predilection for American-built aircraft. Fortunately, the Royal Air Force stepped in and prolonged the type’s lifespan by acquiring examples for transport duties. But total sales of just 54 airframes hardly covered the project’s development costs.

Background

In 1951, Vickers had been contracted by the Ministry of Supply (MoS) to develop a large, jet-powered troop carrier for the RAF, designated the V1000 – a proposed civilian transport version of which, dubbed the VC-7, attracted interest from BOAC. In November 1955, however, with the prototype practically complete, the MoS cancelled the contract, citing defence cutbacks. It was hoped that BOAC would still be keen on the passenger version, but it declined, pointing to delays and other problems it had experienced with other British-made airliners such as the de Havilland Comet and Bristol Britannia.

The VC-7, had it gone ahead, might well have been Britain’s answer to the Boeing 707, but in 1956, BOAC – with government backing – ordered 15 707-400s at a cost of £44 million, each to be powered by Rolls-Royce Conway engines. However, within a few years, BOAC would need to replace its Comet 4s and Britannia airliners on its so-called ‘Empire’ routes. Many of these destinations had short runways which, coupled with ‘hot and high’ conditions, were quite unsuitable for the airline’s 707s. So, by 1957, a new set of specifications emerged from BOAC. These called for a fast jet, capable of carrying loads of 35,000lb (15,876kg) over 4,000-mile (6,437km) sectors to Africa, Australia and the Far East. Although in competition with several other British manufacturers, the Vickers design was subsequently accepted – albeit as a private venture, and the project was designated the VC10.

The VC10 concept

Calling on the expertise gained while designing the V1000, the VC10 concept was based upon an uncluttered wing to give maximum aerodynamic lift, enhanced by the use of Fowler flaps – invented by Harlan D Fowler in 1924, the split flap that slides backwards flat, before hinging downwards, thereby increasing the wing’s chord and then camber – as well as full-span leading-edge slats. Designed for excellent short airfield performance, the wings could also be used to carry most of the fuel. A rear-engined design was therefore called for, together with a high, variable-incidence T-shaped tailplane to avoid jet efflux.

This configuration also gave a higher payload, better economy and, for passengers, much less engine noise. Other gains included reduced fire hazard in the event of a crash and less engine damage due to debris being thrown up from primitive runways. Additionally, various V1000 design features were also incorporated – particularly the use of structural parts machined from solid blocks of metal instead of sheets; and the inclusion of supporting fuselage hoop frames for maximum strength. Room for six-abreast seating was also achieved. The flightdeck technology was also state-of-the-art, with quadruplicated automatic flight control to provide zero-visibility landing capability.

BOAC signed a letter of intent for 25 VC10s in May 1957 with Vickers – reluctantly it appears, since it was already concerned about the aircraft’s operational costs, but the national carrier hoped that other airlines would also purchase the new jet. Meanwhile, Vickers had calculated that its manufacturing breakeven point was 80 aircraft, based on a unit price of £1.5 million. At this stage the proposed VC10 design had an estimated all-up weight of 247,000lb (112,037kg) with a payload of 38,000lb (17,237kg) and seating for 135 passengers. The engines selected were four 16,500lb static-thrust Rolls-Royce Conway turbofans, suspended in pairs either side of the fuselage below the tailplane. The engines were selected to give parity with those on BOAC’s 707-400s, giving the carrier more flexibility when servicing both types.

Development

As the VC10 development proceeded it became clear to the Vickers designers that relatively small changes would give the new airliner a transatlantic capability, enabling it to function over the whole of BOAC’s route network. This could be achieved by increasing the Conways’ power to 18,500lb, adjusting the wing sweep by an additional half a degree and extending the wing span to 140ft (42.7m) to provide greater fuel capacity. Given these amendments to the aircraft’s design, BOAC signed a firm contract for 35 VC10s in 1958, with an option for 20 more examples, with deliveries scheduled to start in 1964.

Much design time was taken up with wind tunnel tests, which refined the wing and the optimum position for the T-tail. Both the fin and tailplane had a greater sweep-back angle than the main wing to ensure that control did not deteriorate at lower speeds. By the end of the development period the gross weight had risen to 312,000lb (141,520kg) and the airliner was to be powered by uprated Conway RCo.42s which each produced 20,500lb of thrust.

BOAC’s own calculations showed that, by 1960, the VC10 would cost £4.24 per passenger-mile to operate, compared to the 707’s figure of £4.10. This internal information was leaked and reportedly led to the loss of several potential overseas orders for Vickers. In fact, there were calls within BOAC to scrap the deal and purchase more 707s instead.

In an effort to bolster interest in the programme, Vickers (now part of British Aircraft Corporation – BAC) began studies on a stretched variant of the VC10 – which would be more economical to fly – designated the Type 1151 or Super VC10. Tailored for the transatlantic market, the fuselage length was increased by 13ft (3.9m) and it could accommodate seating for 163 passengers in an all-Economy Class cabin. Range was increased by an additional fuel tank in the fin torque box, while power was further enhanced with 22,500lb Conway RCo.43 Mk 550 engines.

During the early 1960s Vickers was experiencing financial difficulties and there were doubts as whether it could supply the original order for 35 ‘Standard’ aircraft without making further losses. It offered BOAC the Super VC10 variant at £2.7 million each, only to hear that, due to a poor business forecast, the carrier was not convinced it still required its full commitment of 35 jets. Fortunately for Vickers, the government intervened in May 1961 and a revised contract was signed for 35 Super VC10s plus 15 of the Standard variant. Eight of these were to be constructed as ‘combi’ aircraft with a large cargo door and stronger flooring for future freight/passenger roles. In the event, they were never built.

With first deliveries imminent in 1964, BOAC announced it wanted to cut its original commitment for 35 Super VC10s to just seven, but the government stepped in again and guaranteed to take any over-production as military transports. In fact the total number finally acquired by BOAC was 17. Perversely, the carrier’s orders for 707s remained unchanged and this, together with the prolonged and well-publicised wrangling that went on during this time, further eroded overseas market confidence in the British product.

Entering service

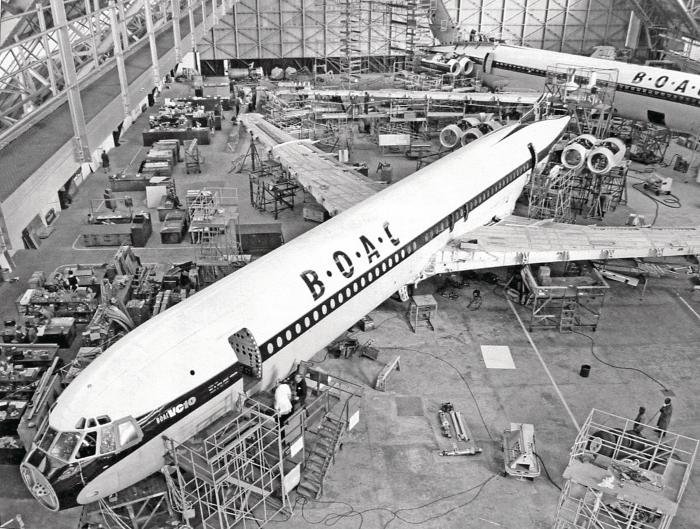

The completed Type 1101 Standard VC10 prototype, G-ARTA (c/n 803), was rolled out of Vickers production sheds at Brooklands, Weybridge in April 1962. After a period of ground testing, it made its first flight on June 29. Vickers’ chief test pilot, Jock Bryce, was at the controls with Brian Trubshaw as co-pilot. They took-off from Vickers’ short Brooklands runway with no problem, proving the type’s short-field performance. Flight testing from the company’s Wisley airfield showed that the expected cruising speed of 580mph (933km/h) was not being achieved, necessitating a few changes: the chord of the leading edge slats was extended and Küchemann wing tip devices which increased the wing’s aspect ratio and reduced drag. This resulted in a final wing span of 146ft (44.5m), while around the rear of the aircraft, beaver-tail shaped fairing extensions were added between the jet pipes of each engine pair to help airflow and further reduce drag.

The first production VC10, G-ARVA (c/n 804), made its maiden flight on November 8, 1962 followed by the second example, G-ARVB (c/n 805), on December 21. There followed two years of intensive flight testing, including visits to Aden, Beirut, Kano, Khartoum, Nairobi and Rhodesia. In these areas, the jet’s ‘hot and high’ performance proved to be entirely satisfactory. The type received its Certificate of Airworthiness in April 23, 1964 and the first example entered service with BOAC six days later on the carrier’s regular rotation from London to Nigeria. Over the next few months the new airliner replaced most of BOAC’s Britannia aircraft and Comet 4s on its African routes and within 18 months it was also being flown to the Far East. But by the time the type entered service, many of the shorter runways on BOAC’s Empire routes had already been extended to accommodate the 707 as well as the Douglas DC-8!

The first Super VC10, G-ASGA (c/n 851), flew on May 7, 1964 and was delivered to BOAC on December 31, 1965. Routes to the West Indies, Canada and the Californian coast were quickly established with the type. Despite BOAC’s initial reluctance to choose the type, it proved extremely popular with crews and passengers alike. The carrier’s customers actually requested to fly on VC10s and crews reported it was easy to fly with minimal aircrew fatigue. In fact, what became apparent was that the aircraft’s speed and comfort translated into fewer empty seats compared to the airline’s 707s. With the Super variant delivering even better economy, the cost per passenger carried averaged £486 per revenue flying hour, compared to the £510 for the 707. These facts were not released by BOAC, however, for it was receiving a handsome subsidy from the government for having to fly the allegedly ‘more expensive’ British airliner. It even declared publicly that its purchase of the VC10 was politically motivated.

British Airways (BA) was formed in 1974 through the merger of BOAC and British European Airways (BEA), and soon after it began retiring the Super VC10s from transatlantic routes. After just ten years they were replaced by wide-bodied jets such as the 747-100 – already flying with BOAC since 1971. The ‘Supers’ replaced the eleven remaining Standard models on the carrier’s Empire routes, with the latter being gradually withdrawn from service. Five of these earlier variants were leased to Gulf Air and two became VIP transports in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, G-ARVJ (C/N 812) and G-ARVF (c/n 808) respectively. All were eventually acquired by the RAF. Three others were actually sold to Boeing as part-payment for another batch of new 707s but, as a final insult, the US manufacturer scrapped them at Heathrow. The last ‘Standard’ Type 1101, G-ARVM (c/n 815), was retained as a fleet back-up until 1979 when it was donated to the RAF Museum at Cosford. It remained there until October 2006 when it was controversially scrapped, the fuselage being transferred to the Brooklands Museum at Weybridge.

The VC10 fleet still had many flying hours left, but the introduction of more stringent noise reduction standards in 1980 meant that BA had two options: develop ‘hush-kits’ for the Conway engines or retire the aircraft. Eventually it decided to withdraw the type from service – but, after a year, BA had been unable to sell any of them to other operators and instead sold 14 of the 15 remaining airframes to the Ministry of Defence; these were destined to be converted into air-to-air refuelling tankers for the RAF. The remaining jet, G-ASGC (c/n 853), was donated to the Duxford Aviation Society and flown to the Imperial War Museum at Duxford on April 15, 1980.

During its service with BOAC and BA, the VC10 had no fatal accidents attributed to the operation of the aircraft. However, one passenger was killed during one of three hijackings involving the type. The fatality, a German banker, occurred on November 22, 1974 when on a BA flight from Dubai, G-ASGR (c/n 867) was forced by terrorists to fly to Tunis. The late Captain Jim Futcher was awarded the Queen’s Gallantry Medal for his actions during the incident. Just a month later, passengers aboard G-ASGL (c/n 862) had a lucky escape when all four Conway engines failed on a flight from Hong Kong to Japan, causing a complete electrical failure. The quick-thinking crew lowered the electrical ram turbine, which provided enough power to restart the engines and the aircraft was able to continue on to Tokyo.

International operators

Overseas operators of the VC10 were confined to Africa and the Middle East. Ghana Airways ordered three Standards in January 1961, although one was subsequently cancelled. The other two were built with the addition of cargo doors and were designated as Type 1102. One of the aircraft, 9G-ABP (c/n 824), was leased by Middle East Airlines from April 1, 1967 until it was destroyed by Israeli commandos in Beirut on December 28, 1968. The other was retired in 1980. East African Airways purchased five passenger/freight Super VC10s (Type 1154) between 1966 and 1970 – in fact the final five examples off the production line.

One of these, 5X-UVA (c/n 881), was involved in the type’s second fatal accident when it aborted take-off from Addis Ababa airport in April 18, 1972. It overran the end of the runway, broke up and caught fire, killing 43 of the 107 on board. The four remaining aircraft continued in operation until they were retired in 1977 when they were returned to BAC and later acquired by the RAF. Air Malawi acquired a single example, 7Q-YKH (c/n 819), from British Caledonian in November 1974 which flew with the African carrier until October 1979 when it was withdrawn from service and stored at Hurn, Bournemouth. It was later flown to Blantyre where, after a further period of storage, it was broken up.

Meanwhile, back in the UK British United Airways (BUA), which later became British Caledonian, acquired four examples of the type: two ‘combi’ Type 1103s in 1964, the Type 1102 previously cancelled by Ghana Airways and, in 1969, the prototype, G-ARTA, which had been converted to a Type 1109 for Laker Airways. This aircraft was written-off in a landing accident at Gatwick in 1972 while flying with British Caledonian. One of BUA’s former VC10s, G-ASIX (c/n 820), was sold to the Sultan of Oman in 1974 and converted into a ‘flying palace’. When the Sultan upgraded his personal transport, his VC10 was donated to the Brooklands Museum. Nigerian Airways initially ordered two Standard jets in 1969, but later decided it couldn’t afford them, instead leasing the second production aircraft, G-ARVA, from Vickers. This example was involved in the type’s first fatal accident – when flying as 5N-ABD, it crashed while landing in Laos on November 20, 1969, killing all 87 passengers and crew on board.

Marketing efforts were made in other countries including Mexico, Argentina, Lebanon, Thailand, Czechoslovakia and Romania – without success. One serious enquiry was received from the Chinese State Airline (CAAC), but by the time it was ready to place an order, the production jigs had already been broken up by BAC.

Military operators

The longevity of the VC10 design can be credited to its secondary role as an RAF transport/tanker aircraft – which continues today, some 50 years after the prototype made its maiden flight. In 1961, the Air Ministry signed a deal for five VC10 transport variants to meet their specification C 239 – an order later increased to eleven when, as previously mentioned, BOAC reneged on its original commitment. These were followed three years later by a deal for three Super VC10s. All were designated as Type 1106 and built with a cargo door, reinforced flooring and an extra fuel tank in the fin, and were powered by Conway RCo.42 turbofans. In addition, they received an air-to-air refuelling nose probe and an auxiliary power unit in an extended tail cone. All 14 were designated C Mk.1s by the RAF and were operated from RAF Brize Norton.

In 1977, the RAF placed a contract with British Aerospace to convert five redundant BOAC Standard VC10s and four ex-East African Airways Super VC10s into air-to-air refuelling tankers; these were designated as K2s and K3s respectively. Four years later, 14 former BA jets were acquired by the MoD and initially placed in storage at Abingdon for spare part reclamation. In 1990, five of the more complete airframes were converted to K4 tankers. At this time, 13 of the original C Mk1s remaining in service were also converted into a dual transport/tanker role, designated as C1Ks.