Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Wifredo Lam: From Cubist to Cuban

Melding Afro-Caribbean and European influences, Wifredo Lam created one of modernism’s most distinctive bodies of work.

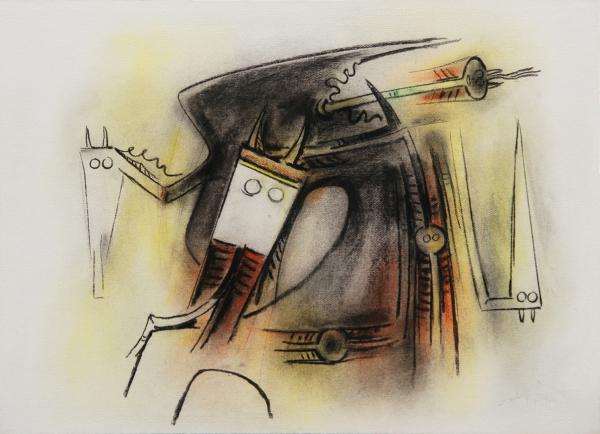

Wifredo Lam, Figuras de Trópico (Figures of the Tropics), 1966, pastel on heavy paper laid down on board, 22 x 29 ¾ in

Featured Images: (Click to Enlarge)

- Wlfredo Lam, Gallo Caribe (Caribbean Rooster), 1944, oil on canvas, 11 ½ x 9 3/4 inches;

- Wilfredo Lam, Femme Enigmatique 1970, oil on canvas, 63 x 51 inches.

- Wifredo Lam, Figuras de Trópico (Figures of the Tropics), 1966, pastel on heavy paper laid down on board, 22 x 29 ¾ in

- Wilfredo Lam, Ídolo (Idol), 1970, oil on canvas, 19 5/8 x 15 ¾ in.

- Wilfredo Lam, From top: Mujer Sentada (Seated Woman), 1944, oil on paper laid down on board, 42 x 33 in.;

- Wilfredo Lam, Femme Masquée (Masked Woman), 1973, oil on canvas 17 7/8 x 13 ¾;

In art-historical terms, what a conundrum the work of the Cuban-born modernist Wifredo Lam (1902–82) presents for the more inflexible keepers of the familiar, canonical story of modern art’s evolution, in which one style begot another in a more or less straight, sometimes zigzagging line. Today, Lam’s art can be hard to place neatly in a single category whose label embraces all the varied ideas and influences that helped shape his oeuvre.

For starters, unlike some of the largest-looming protagonists of modern art’s familiar historical narrative—Cézanne, Picasso, Matisse and others—he was neither white nor European. Instead of the urban-bourgeois, rationalist, primarily Judeo-Christian cultural background many of modernism’s early developers shared, the society, culture and political setting in which Lam was born and grew up, typical of those of the so-called New World, were multilayered and multiethnic, the products of an often painful colonial past. (Indeed, Cuba gained its independence from Spain only seven months before Lam was born.)

Similarly, today, the complexity of Lam’s work has attracted admirers not only of definitive forms of Latin-American modernism but, at the same time, art aficionados well versed in the context-questioning principles of postmodernist critical thinking. As a result, in recent decades examinations of Lam’s accomplishments have sought to position the artist and his work not so much in terms of what he might have assimilated from his precursors and peers, but rather in terms of what this peripatetic painter, sculptor, draftsman and printmaker contributed to modern art’s ferment.

Wifredo Oscar de la Concepción Lam y Castilla was born and brought up in Sagua la Grande, a coastal city in north-central Cuba. His hometown is known for its “río undoso,” the wavy river around which it developed. In the region’s colonial past, the labor of slaves imported from Africa and of immigrants lured to Cuba from China was exploited to cultivate sugar cane and other crops. Lam’s trader father was an immigrant from Canton (now known as Guangzhou, in southern China); his mother’s ancestors were African, European and indigenous to the island.

The young Wifredo grew up in an environment filled with lush vegetation and the light and colors of a home by the sea. He was surrounded by people of African ancestry who, like his own family, were familiar with or practiced Santería (also known as Lucumí), a belief system that combines aspects of Roman Catholicism with the Yoruba religion of West Africa. Through his godmother, a Santería priestess, he was exposed to rituals that honored African deities.

In 1916, Lam moved to Havana, where he was urged to study law. However, he liked to draw tropical plants in the city’s botanical gardens and ultimately enrolled at its art school, the Academia de San Alejandro. In Havana, Lam took part in salon-style exhibitions and in 1923, after winning a grant from the municipality of Sagua la Grande to study in Europe, headed to Spain, where he intended to stay for a short time before moving on to Paris. Before leaving Cuba, Lam’s family arranged for a Santería priest to send him off with a good-luck ceremony in which two guinea hens were sacrificed.

As it turned out, Lam’s Spanish sojourn lasted more than a decade. In Madrid, he visited the National Archaeological Museum and that venerable repository of Spanish masterpieces, the Museo Nacional del Prado, where he examined the works of Velázquez and Goya and was struck by the fantastic imagery of Hieronymus Bosch and the paintings of the Flemish artist Pieter Brueghel the Elder. During this period, Lam also discovered the work of Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin. “In the Prado, I had the impression of being a guest at a sumptuous banquet,” Lam would later tell the French art critic Max-Pol Fouchet.

In Spain, Lam studied with Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor y Zaragoza, a painter who served as director of the Prado. Photos from that time show the Cuban artist looking dapper in double-breasted suits as he promenaded with artist friends in Madrid. His own work evolved away from academic-style landscapes and portraits—he disliked those genres and traditional art-school training—as he became aware of modern art’s simplifying approaches to color and form. Lam married for the first time, but his wife and their infant son died of tuberculosis in 1931. A devastating event for the artist, the loss of his young family inspired his subsequent treatment of the mother-and-child theme in his art.

As the decade of the 1930s progressed and civil war erupted in Spain, Lam sided with the Republicans against Generalísimo Francisco Franco’s forces. He joined an international group of artists in the fight against fascism and helped create propaganda posters for the Republican cause. In 1937, he produced a cri de coeur inspired by the conflict, the large-scale, gouache-on-paper drawing, La Guerra Civil (The Civil War, now in a private collection). A dynamic composition, it is filled with the ominous thrusts of fighters’ pointed rifles and the contortions of cowering, slain or wounded human bodies.

In the early 1930s, the influence of Surrealism could be seen in Lam’s work. His encounter with Picasso’s ideas and techniques in an exhibition of the Spanish-born modernist trailblazer’s art, which was shown in Madrid in 1936 also had a big impact on him. Picasso was 21 years older than Lam, and the heyday of his ground-breaking contributions to the development of Cubism was behind him. Two years after seeing the master’s show and armed with a letter of introduction to him from the Catalan sculptor Manolo Martínez Hugué (known as Manolo), the Cuban artist moved to Paris. There, he met up with old friends, including the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda and the Cuban writer and musicologist Alejo Carpentier, and visited the Louvre. Lam felt a mixture of excitement and trepidation at the prospect of meeting Picasso, whom he first saw but did not approach at an exhibition of 19th-century painting.

Soon, though, bearing Manolo’s letter, Lam did call upon the legendary Spaniard, who described their encounter as “love at first sight.” Picasso brought Lam into a community of artists, writers and thinkers that included such luminaries as Georges Braque, Fernand Léger, Joan Miró, the Surrealist poet Paul Éluard and the art dealer-collector Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. The German-born Kahnweiler, who had opened his first gallery in Paris in 1907, had championed Picasso, Braque and other pioneering modern artists and had become closely associated with Cubism; through Picasso, Lam also met the Surrealist writer and ethnographer Michel Leiris, who in 1926 had married Kahnweiler’s stepdaughter and would later write about Lam’s work. Lam later observed that, for him, meeting Picasso, whom he described as an “instigator of freedom,” had been “like an electric shock.”

Picasso’s collection of African masks and sculptural objects made a big impression on Lam when he saw the older artist at his studio on the Rue des Grands-Augustins. In 1907, Picasso had visited the Trocadéro Museum of Ethnography in Paris (now the Museum of Man), where he had been deeply moved by the forms and auras of masks and sculptural works from Africa and Oceania. Lam later said that “the presence of the aesthetic and spirit of African art” that he apprehended among the objects at Picasso’s studio was powerful and fascinating for him. The older artist introduced Lam to Leiris, who worked in the ethnographic museum’s Africa department and was able to answer his questions about what was then known as “l’art nègre,” or “Negro art”; more generally, in that era nearly a century ago, masks, carvings, ritual objects and artifacts from Africa, Oceania and other “underdeveloped” or “uncivilized” parts of the world were still regarded as “primitive.” (Since then, critical thinking about the character and classification of such objects has changed.) Some of Lam’s canvases from the 1930s show the strong influence of Matisse; many others feature male or female figures whose simplified, geometric forms are rendered with bold outlines, their faces literally blank or ambiguously expressive, with dark-slit eyes, broad noses and big nostrils, or plain, flat stripes for noses.

Moving into the 1940s, in what would become known as some of his most emblematic works, Lam fused stylized representations of human faces and figures, Surrealist-fantastic drawing (with a precise, knowing line) and Cubist-influenced, energized pictorial space. This technical-stylistic cocktail, with its evident nod to Lam’s familiar Afro-Cuban sources, too, became his signature contribution to modern art’s still-evolving modes of abstract and semi-abstract expression.

It can be seen in numerous works of Lam’s from that period, with their animal-like human forms that appear to be wearing masks or other mysterious beings whose wide eyes, horns, wings or appendages seem to give visible form to the sensed presence of otherwise fleeting spirits. In time, such subjects would give way to countless depictions of various spindly creatures whose pointed heads and strange protrusions became hallmarks of Lam’s imagery.

Interaction with other cultures and with artists in other countries played a meaningful role in the development of Lam’s art and ideas. In 1938, he visited the artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Mexico, and a year later he presented his first solo show in Paris to considerable acclaim at the dealer Pierre Loeb’s gallery. In 1940, after the Germans invaded Paris, Lam headed south to Marseille. There, at a crumbling mansion on the outskirts of the city, Surrealism’s leader, André Breton, his family and a parade of other artists—André Masson, Max Ernst, Jacques Lipchitz, the poet Benjamin Péret, Remedios Varo and others—passed through or bided their time anxiously as they waited to obtain permits to leave France for the U.S. or other safe havens. Lam spent time there, too, and collaborated on a project with Breton—he illustrated the Surrealist’s poem “Fata Morgana.” In early 1941, Lam; his companion, Helena Holzer (a German chemist, who later would become his second wife); Breton and his family; the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss and a legion of other artists and intellectuals left Marseille by ship, bound for Martinique. From there, Lam and Holzer eventually made their way to Cuba, where they would stay for several years, and the artist would reconnect artistically, intellectually and spiritually with his homeland.

In Cuba, Lam mixed with other artists, painters and writers. His sister arranged for Lam and his associates to attend Santería ceremonies, with their dramatic drumming and dancing. Lam, who was aware that, in the past, enslaved Africans had been forbidden to make visual art—they were allowed to sing, dance or tell stories—embraced his cultural ancestry and melded vivid evocations of it into his work. Of his return to his native island, he observed, “For me, seeing Europe had been everything. When I came back to Cuba, I was taken aback by its nature, by the traditions of the blacks, and by the transculturation of its African and Catholic religions. And so I began to orientate my paintings toward the African.”

The light and atmosphere of Cuba, its vegetation, the closeness of its people to the earth and, above all, the African cultural heritage that many of them shared—Lam brought together all of these elements and more in his best-known painting, La Jungla (The Jungle, now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York), which he began working on in late 1942 and finished the following year. Later Lam would note that, with his large-scale picture’s gathering of tall, totem-like, half-human, half-animal figures packed closely together in a thicket of sugar cane or bamboo, he had “intended to communicate a psychic state.”

In retrospect, it might be said that the European modernists and Lam assimilated non-Western—specifically, African—sources through different cultural and historical filters. However, the Cuban artist absorbed such influences as much through his own native cultural-historical experience as through the theoretical-aesthetic apparatus the Cubists, Surrealists and other inspiration-seeking European modernists had constructed. “Forms that live in space and in matter live in the spirit,” the French art historian Henri Focillon wrote in his compact treatise, Life of Forms (1934). In much of his work, Lam showed that the converse of that observation could be true, too.

In the early 1950s, Lam returned to Europe, where he settled in Paris, married again and later established a second home and studio in Italy. His work was the subject of numerous gallery and museum exhibitions, and in the period immediately following Fidel Castro’s revolution in Cuba, which overthrew the U.S.-backed dictator, Fulgencio Batista, in 1959, Lam was active in the cultural life of his homeland, where he painted The Third World (1965–66), his self-described “artistic tribute to the Cuban Revolution,” for the presidential palace in Havana. Later in his career he began making ceramics.

By the time he died in 1982, Lam had established a secure place in art history as an inventive assimilator-explorer, whose fusion of personal and stylistic elements was a notable part of modern art’s evolution. Meanwhile, a younger generation of critics and scholars began to regard him as a prototypical postmodernist, whose visual-formal mash-ups, to use a term from the digital age, had presaged the identity politics and appropriated-from-multiple-sources pastiches of the post-Pop era.

Lam certainly did not regard himself as a mere copier. Speaking of Picasso, he once told Fouchet: “Everybody has felt [his] influence, for Picasso was the master of our age. Even Picasso was influenced by Picasso!…There was no question of imitation, but Picasso may easily have been present in my spirit, for nothing in him was alien or strange to me. On the other hand, I derived all my confidence in what I was doing from his approval.” Fouchet observed that Lam’s images, “born of dream and reality,” had come to the artist “from some inner remoteness.” For Leiris, in part, through his art, “Lam undertook to bring to light his destiny as a West Indian man of color, claiming to be a man in his own right”—implicitly and explicitly rejecting former European colonizers’ patronizing, prejudicial attitudes vis-à-vis the colonized.

“Lam’s enduring contribution to world art history was the reclamation and projection of an African identity within mainstream art history,” notes Lowery Stokes Sims, an art historian and curator at the Museum of Arts & Design in New York who has written extensively about Lam and organized museum exhibitions of his work. Today, it is attracting the interest of collectors of emblematic examples of modern art and, more specifically, of Latin American modernism; at the same time, notes dealer Ramón Cernuda of Cernuda Arte in Coral Gables, Fla., which offers a range of Lam’s paintings, drawings and prints, it appeals to admirers of works by artists of the so-called African diaspora, too. Lam’s finest available paintings and works on paper can cost from $40,000 to $60,000 or more.

Through his art, Lam sought a way to convey the spirit of Afro-Cuban culture, which had thrived even in the face of colonial-era oppression, and to honor those dislocated Africans who, he once remarked, had “brought their primitive culture [and] their magical religion, with its mystical side in close correspondence with nature,” to his homeland. In one of modern art history’s most interesting twists, whereas Europeans like Picasso and Breton had been smitten by—and intellectually romanticized—their discoveries among the “exotica” of non-Western cultures, a sense of appreciation Lam would come to understand through his association with such colleagues, the Cuban artist also could—and did—approach such source material from a personal vantage point. It was one from which an African aesthetic and spiritual sensibility were really not so “foreign” after all.