Energy sector Exploration & Production (E&P) companies work in a cyclical market dictated by the oil price. Oil price and production volumes determine free cash flow which in term impacts capital expenditure on new projects and the contracting strategies relating to existing projects.

Rotorcraft operators, owners and OEMs working in the oil and gas industry are all exposed to this cyclical activity which presents both opportunities and challenges in both the upcycles and down cycles.

A prolonged oil industry downturn forces E&P companies to cut costs in order to protect free cash flow (many of them are publicly listed and often the shareholders own them for the high dividend yield.)

The entire oilfield services (OFS) business (of which the rotorcraft industry forms a small but vital part) thus comes under pricing pressure. Asset-heavy businesses that rely on costly capital equipment to support their work (such as the drillers and indeed the helicopter companies) rarely fare well in such a downturn and it is no surprise that many rig owners, vessel companies and helicopter operators have seen financial restructuring processes in the last 5 years.

Re-organising debt is only part of the solution, however. Once you have hit the ‘reset’ button, how do you then adapt your business to the market reality, where the customer is looking for cost efficiency in every aspect of the supply chain? In a safety critical business such as aviation, this evidently requires extreme care.

One area of focus is fleet management. Helicopter ownership requires a significant capital outlay, so getting the most out of that outlay is important. The days of specific ‘dedicated’ helicopters to individual contracts are mostly gone in the busy helicopter hubs as E&P companies come to understand that being able to point at a specific aircraft and say “that’s our chopper” isn’t of much value vs being able to say “we’ve got a flight at 7am tomorrow”. This allows helicopter operators to spread a fleet across multiple clients and reduces the number of idle aircraft and in-turn reduces the overall fleet size required to service a portfolio of clients.

Moving beyond that, helicopter operators need to decide whether to lease or own aircraft, and how to maintain them. It is often said that leasing is far less prevalent in the rotorcraft market vs the fixed wing market and this is true, however, in the most demanding (and most expensive) applications that require Heavy and Super-Medium helicopters there is a well-established, highly professional and competitive leasing business that has developed over the last two decades. Over 40% of the crew transfer S-92 fleet is owned by lessors Milestone, Macquarie, LCI and Lobo. The benefits of leasing are well understood as Nigel Leishman succinctly summarised for us in an interview last year. Leases can be timed so that they line-up with end-contracts with customers – reducing risk for the operator.

“the leasing product appealed to operators who wanted to realise capital (sale & leasebacks) or couldn’t afford to fund the aircraft themselves. Our clients make a long term commitment to the aircraft (LCI leases are typically around 7-10 years but can be as short as 5) but without enormous Capex commitment upfront. Lead-times (if aircraft are already on order or available) are also much shorter which helps when the end-client can often make decisions at the last minute… sometimes only a few months before the aircraft are required!”

With regard to the S-92 the market is currently centered around remarketing rather than speculative or 5 year leases so we see a different dynamic at present but nevetheless using this leasing market has been an essential fleet management tool for many operators. In the Heavy market, Babcock’s S-92 fleet is entirely leased, CHC likewise rely extensively on leased aircraft whereas only 44% of Bristow’s oil & gas S-92 fleet is leased.

S-92 Operators Need To Remain Competitive

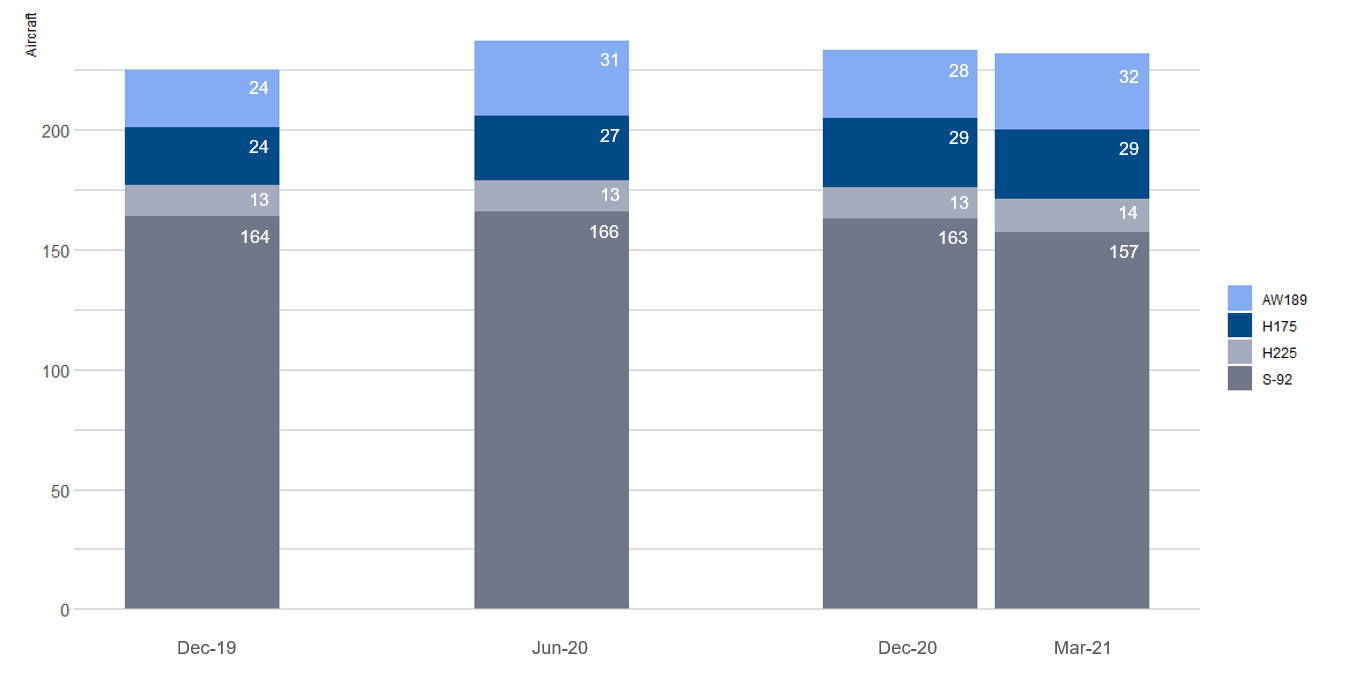

S-92 operators have been under pressure. Not just due to the supply chain ‘squeeze’ noted above but also in terms of maintaining the competitiveness of the aircraft vs alternatives such as super-mediums including Airbus’ H175 and Leonardo’s AW189. As we have noted previously this year, the S-92 has lost ground to the super-mediums in terms of the share of the active heavy & super-medium fleet.

Active Crew Transfer Heavy & Super-Medium Rotorcraft. Source: S-92 Fleet Census Q1 2021, Air & Sea Analytics

Operators have both the cost of ownership (lease or buy) and the operating cost to consider and manage. In an over-supplied market the cost of ownership tends to fall as competition between lessors drives lease rates down. The operating cost reflects a number of different cost components but key items are maintenance and parts.

Many of the fleet are flying on Sikorsky’s power-by-the-hour programme (TAP) which sees operators pay an hourly rate to Sikorsky and when a new part is needed Sikorsky will deliver it (or the operator takes it from consignment stock) with nothing more to pay. Airbus and Leonardo have similar programmes for their aircraft as do the engine suppliers. Aircraft on such programmes therefore have an element inherent in their value reflecting the sums committed to a PBH programme.

This value consideration makes operators unwilling to scrap aircraft or take them out of a PBH programme and this is a key reason why we have seen very little scrapping of aircraft in this downturn (compared to the drillers that have scrapped ¼ of the mobile fleet). By their nature these heavy and super-medium aircraft are all different designs with varying payload, radius of action etc and PBH costs vary. The annual escalation in PBH costs also varies and some operators and owners have been complaining that in this regard the S-92 has been at a disadvantage, or to put it another way, quoting an anonymous owner, “a 4% escalation compounds pretty quickly!”

Boxing Clever – Safely Mitigating Cost Pressures

What can operators do with their fleet faced with escalating costs and working in a competitive market where controlling expenditure is key to maintaining market share and securing new business?

1. Reduce overall cost of ownership by operating fewer aircraft – amidst lower demand, fewer aircraft are needed so excess aircraft on lease can be returned. It sounds obvious but depending on lease terms it can take time to return leased aircraft. The operator may have to wait until the end of the lease term and it will likely have to incur costs in repainting the aircraft and undertaking any maintenance required. This approach also applies to aircraft that are owned outright as they can either be sold or leased to other operators (e.g. NHV recently leasing excess H175 aircraft to OMNI)

For: lower overall aircraft ownership costs.

Against: Leaves fewer aircraft available to bid into ad-hoc or shorter-term contracts.

Examples: Bristow lease returns to VIH, Milestone.

2. Reduce average cost of ownership by opportunistically acquiring aircraft for sale – the series of bankruptcies amongst operators in this cycle led (or forced) some lenders to repossess aircraft. These aircraft have been difficult to sell or put to work on new contracts (a bank is typically skilled at banking but not aircraft leasing) and as a result many have (after a period of time usually measured in years) been sold at prices that are attractive to operators and lessors that may be able to put the aircraft to work.

What if you have the ability to deploy out-of-work S-92s owned by banks but not the upfront cash to buy them? CHC have been rather shrewd here in adding four aircraft to their fleet but only buying one up-front whilst the other three are on lease-to-own arrangements with balloon payments at the end of the lease.

For: Dilutes overall cost of fleet (per aircraft). Expands fleet allowing more contracts to be bid. Potentially provides parts for other aircraft (see below).

Against: Up-front capex requirement (even if you think a $5m S-92 is a great buy, you still have to find $5m upfront to buy it!). If you don’t find work for the aircraft then you need to ensure you can extract value in other ways (see 3 below)

Examples: Milestone acquired several S-92s from companies such as Element Capital and Banc of America Leasing & Capital at prices rumoured to range from $4m to $6.5m. Macquarie Rotorcraft Leasing acquired 120 heavy and medium helicopters at circa 40 cents in the dollar as part of the Waypoint bankruptcy. VIH acquired a SAR aircraft from Japan that had water damage to the landing gear in a typhoon. CHC have acquired aircraft from the likes of PNC and MUFG, either outright or on ‘lease to buy’ arrangements.

“every so often we do see opportunities where something is available for a price that’s substantially below the economic value we believe we can extract from the asset. In those circumstances, we are making opportunistic purchases. It’s about where we see a mismatch between the price of an asset being sold by a distressed seller and what we can extract… and that’s when we deploy capital.”

3. Run your own PBH programme and/or acquire parts – a number of the operators have MRO businesses and some of these, such as Heli-One, run PBH programmes for certain types of aircraft for both their parent companies and other helicopter owners. The challenge with an S-92 is the availability of parts – if you are trying to reduce cost by sourcing parts elsewhere, where are they going to come from? The trick to this strategy is combining it with no. 2 above – aircraft acquired at a lower cost can be ‘parted out’ providing a source of components that effectively sidesteps the OEM.

For: Lower operating costs

Against: May negatively impact aircraft valuation vs an OEM PBH programme. You need a source of parts which is fine when utilisation of the fleet is not 100% but difficult in a booming market and if you have to source parts from the OEM you negate some of the cost saving. (Vice versa, it’s entirely possible to end up with too many parts and not enough aircraft flying enough hours to consume them.)

Examples: CHC/Milestone/Heli-One.

S-92 Fleet Movements (by Operator or Lessor if not on lease) July 2020 - Jun 2021.

Summary

Operators and lessors are finding ways of satisfying the end-users need for cost efficiency through a number of fleet management strategies. Bristow devoted a whole page in its latest presentation to lease returns in contrast to CHC which appears to be employing a different strategy.

Thus far, the OEM itself has yet to intervene in the market in a similar way, however it is uniquely well-placed to employ some of these same strategies and could well engage in the market in the future. This would most likely occur through reducing excess capacity via part-outs and subsequently supporting clients with options for certified parts with a good useful life remaining. By reducing excess capacity it would bring forward the time at which new S-92 orders are required as the oil and gas recovery progresses.

Steve Robertson, Air & Sea Analytics.

June 30th 2021

As a reminder, our latest S-92 fleet census is now available. Providing unit-by-unit detail on current status and location for the offshore crew transfer fleet the report is ideal for stakeholders in the S-92 business and likewise for those that work with competing aircraft. We use state-of-the-art data analytics techniques combined with good old-fashioned primary research to establish who is operating the aircraft, where, and how that has changed. For more detail see here: