Abstract

This paper uses individual-level data covering 30 transition countries that account for over one-quarter of the worldwide immigrant stock to assess the impact of risk aversion on willingness to migrate. It extends the previous literature by allowing the effect of risk aversion to depend on the level of risk in the sending country. Consistent with theories of individual-level migration decisions, we find that risk aversion has a robust and statistically significant negative impact on willingness to migrate within countries as well as abroad. As predicted by theory, this impact is robustly less negative in riskier sending countries. Furthermore, this negative impact is significantly larger for willingness to migrate abroad than willingness to migrate internally. We also find that, even after controlling for an extensive set of control variables, willingness to migrate internally and abroad are highly correlated. This suggests that internal and international mobility decisions are closely linked.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Ever since the seminal work of Sjaastad (1962) and Harris and Todaro (1970), economists have modeled migration as an investment decision under uncertainty. Decision makers pay the financial and psychological costs of migration up front in order to reap the benefits of higher expected lifetime utility later. Since these benefits are uncertain, economic theory implies a close link between risk attitudes and the propensity to migrate. Only few contributions, however, provide direct evidence on the impact of risk aversion on migration decisions at the individual or household level, and those that do mostly focus on risk aversion as a determinant of migration within countries. For example, Jaeger et al. (2010) find that migrants between German regions are more risk loving than their immobile counterparts. Conroy (2009) finds the same for emigrants from rural Mexico, as do Akgüç et al. (2016) and Dustmann et al. (2017) for rural-urban migrants in China. Direct evidence on the importance of individual-level risk aversion for international migration is even more limited. To the best of our knowledge, only Gibson and McKenzie (2011) and Nowotny (2014) provide direct evidence on the role of risk aversion in international migration. While the former focus on a highly selective sample of the “best and brightest” high school students from three Pacific states (New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, and Tonga), the latter mostly focuses on the role of risk aversion in the choice between cross-border commuting and migration.Footnote 1

This paper uses a large-scale, multi-country individual-level dataset (the Life in Transition Survey, LITS) to provide direct evidence on the impact of risk aversion on the propensity to migrate across and within countries in a unified framework. This data provides information on migration intentions both within a country and abroad for 30 transition countries that, according to Özden et al. (2011), account for over 25% of worldwide migrant stocks. It also contains a measure of risk aversion whose reliability has been experimentally validated by Dohmen et al. (2011).

This data allows us to consider potential migrants relative to the general population in the sending country and to compare the impact of risk attitudes on the propensity to migrate abroad and within countries. The data source also surveys potential migrants prior to migration, which makes issues related to the potential impact of migration experiences on risk attitudes, a cause of endogenous attitudes toward risk in data on actual migration (see Jaeger et al. 2010), of less concern. Further, the focus on a broad set of sending countries lets us explore whether risks that are specific to the sending country moderate the relationship between individual-level risk aversion and the propensity to migrate. This is of interest because Jaeger et al. (2010) argue that, although more risk averse individuals should be less prone to migrate, the negative impact of risk aversion on migration decisions could be weaker (or potentially even be reversed) in countries with high risks if risk averse persons dislike living in a risky (region of a) country. The overall effect of risk aversion on migration propensities is therefore ambiguous and likely to depend on the riskiness of the sending country.

We base our analysis on a model of immigrant self-selection and find that, in accordance with the previous literature, risk averse individuals are less likely to be willing to migrate both abroad and within countries. We expand the existing evidence by showing that this impact is less negative in riskier countries. Somewhat surprisingly, this applies not only to willingness to migrate abroad but also to willingness to migrate within a country. We also find that willingness to migrate within a country and abroad are highly correlated even after controlling for a broad set of observable characteristics. This can be taken as evidence that (unobserved) factors that impact migration costs abroad and within countries are highly correlated. In addition, individual-level risk aversion reduces willingness to migrate abroad more strongly than willingness to migrate within a country.

2 Theory

To provide testable hypotheses for our empirical analysis, we build on a standard model of immigrant self-selection (e.g., Borjas 1991) and model the choice of individuals (i) that differ in their risk attitudes (αi) among locations (k) that differ in their risk characteristics. Further, we add to the existing literature by allowing for a (potentially correlated) choice between migration within and across countries. The central trade-off in this model is that on the one hand, risk averse individuals want to avoid living in risky regions (countries) and thus prefer to migrate to low-risk regions (countries), while on the other hand, more risk averse individuals also want to avoid migration because it is in itself an undertaking with uncertain benefits.

Individuals derive utility from expected future lifetime log-income \( {w}_k^i \) net of migration costs in location k according to an exponential utility function exhibiting constant absolute risk aversion (CARA):

The location k is either the current region of residence (denoted by h), another region of the individual’s home country (denoted by e), or another country (denoted by a) such that kϵ{h, a, e}. Individuals choose between these three potential locations that differ not only in terms of the expected lifetime income and the costs involved in moving to them, but also in terms of their income uncertainty.

If individuals do not move (i.e., k = h), migration costs \( {c}_{hh}^i \) are zero. By contrast, individuals who move within the country encounter (financial and psychological) migration costs of \( {c}_{he}^i={\overline{c}}_e^i+{\eta}_e^i \), while these costs are \( {c}_{ha}^i \)=\( {\overline{c}}_a^i+{\eta}_a^i \) when moving abroad. \( {\eta}_e^i \) and \( {\eta}_a^i \) are individual-specific cost components unobserved by researchers but known to individuals. \( {\overline{c}}_e^i \) and \( {\overline{c}}_a^i \) are average migration costs related to observable characteristics known to both researchers and individuals. The magnitude of these costs and their (observed and unobserved) determinants may differ for internal and international migration, but they are potentially correlated. Both theory and empirical results suggest that international migration costs are higher than internal migration costs because of the greater geographical, cultural, and linguistic distance involved in cross country moves. Consequently, we assume that the expected costs of international migration exceed those of internal migration (i.e., \( {\overline{c}}_a^i>{\overline{c}}_e^i \)).

Individuals are also imperfectly informed about lifetime income opportunities in all regions but have the best (i.e., least noisy) information on their region of residence and the worst (i.e., nosiest) on income opportunities abroad. Lifetime income at location k is assumed to be given by \( {w}_k^i={\mu}_k^i+{\varepsilon}_k^i \), with \( {\mu}_k^i \) the expected log-income of individual i living in region k (which, again, depends on individual characteristics such as age and education) and \( {\varepsilon}_k^i \) an individual and region-specific income shock with variance σk2. This is directly related to the imperfection of information on earning possibilities in the respective region of residence and measures the extent of income uncertainty in region k. It is thus lowest in the place of residence and highest abroad (i.e., σa2 > σe2 > σh2).Footnote 2

Under the assumptions on the utility function and of normally distributed income shocks \( {\varepsilon}_k^i \), the Arrow-Pratt approximation is exact (see Eeckhoudt et al. 2011). Therefore, after substituting the wage and migration cost equations into the utility function and taking expectations, the expected utility associated with staying in the region of residence is \( E\left[u\left({w}_h^i\right)\right]=-{e}^{-{\alpha}_i\left({\mu}_h^i-{\sigma_h}^2{\alpha}_i/2\right)}/{\alpha}_i \), that of moving abroad \( E\left[u\left({w}_a^i\right)\right]=-{e}^{-{\alpha}_i\left({\mu}_a^i-{\overline{c}}_a^i-{\eta}_a^i-{\sigma_a}^2{\alpha}_i/2\right)}/{\alpha}_i \) and that of moving to another region in the same country \( E\left[u\left({w}_e^i\right)\right]=-{e}^{-{\alpha}_i\left({\mu}_e^i-{\overline{c}}_e^i-{\eta}_e^i-{\sigma_e}^2{\alpha}_i/2\right)}/{\alpha}_i \). Comparing these expected utilities, an individual prefers to move abroad rather than stay (i.e., is willing to move abroad) if:

and to move to the other region of the same country rather than stay (i.e., is willing to move internally) if:

Equations (1) and (2) show that the probability of being willing to migrate depends not only on differences in expected incomes between the receiving and sending region (i.e., \( {\mu}_k^i-{\mu}_h^i \)) and average migration costs (\( {\overline{c}}_k^i\Big) \), but also on individual-level risk aversion (αi) and country level risks (σk2).Footnote 3 These equations thus provide two testable predictions: First, as also shown in the previous literature, risk aversion αi has a negative effect on individual migration propensity. Second, the negative impact of risk aversion on the willingness to migrate will be less pronounced in riskier regions (regions with higher σk2), because (all else equal) the disutility of living in a riskier country is larger for more risk averse persons than for less risk averse ones.

3 Data

We use data from the second wave of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s Life in Transition Survey (LITS) conducted in 2010 to test these predictions.Footnote 4 This is one of the standard datasets for the analysis of social developments in transition economies and has among others been used by Nikolova and Sanfey (2016), Cojocaru (2014), and Broulíková et al. (2017). It collected information on 33,360 individuals in 30 transition countries which according to Özden et al. (2011) account for over 25% of the worldwide stock of foreign born. For each country, the survey randomly selected 75 (in Uzbekistan, Serbia, and Poland) or 50 (in all other countries) local electoral units and subsequently randomly chose 20 households within each local electoral unit and one person within each household as a respondent. As the dependent variable in the analysis (discussed below) measures job-related mobility intentions, we restrict our sample to the working age population (between 16 and 65 years old) to exclude persons for whom job issues are not that relevant in their mobility choices. After additionally excluding persons with missing information, we end up with 23,479 observations in total and between 585 (Estonia) and 1124 (Poland) individual-level observations for each country.

3.1 Dependent variables

The questionnaire included two separate questions on respondents’ willingness to migrate posed independently of each other.Footnote 5 The first asked whether respondents are willing to migrate to another region of the same country for job-related reasons. The second asked if they are willing to move abroad for job-related reasons. These questions mirror the choices modeled above, as they confront respondents with two separate but potentially correlated choices on their (job-related) willingness to migrate abroad and within a country. Persons who answered the first question affirmatively were thus encoded as willing to migrate abroad (\( WT{M}_a^i=1 \), zero else) and those answering the second question positively as willing to migrate internally (\( WT{M}_e^i=1 \), zero else). The resulting dichotomous variables are used as the central dependent variables in the analysis.

The data therefore focuses on migration intentions rather than realized migration and thus considers potential rather than actual migrants. This has some advantages but also holds potential drawbacks. One advantage is that measuring migration intentions at a time before respondents migrate allows us to compare the risk attitudes of potential migrants relative to the population of the sending region, which is more complicated in data on realized migration (see e.g., Borjas 1991).Footnote 6 Further, issues related to the potential impact of past migration experiences on risk attitudes, which may be a cause for the endogeneity of risk attitudes in actual migration data (see Jaeger et al. 2010), are of a lesser concern, as respondents in the questionnaire have not yet migrated.

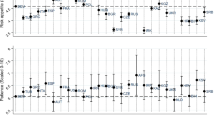

The drawbacks are that this dataset does not contain information on the receiving country and its characteristics and that migration intentions may or may not be realized. The former implies that the current analysis cannot directly control for factors that are mentioned as important determinants of migration in the literature (e.g., Docquier et al. 2014), such as receiving country risks, income, and employment prospects as well as a person’s network abroad. We therefore must rely on sending-country fixed effects to capture these factors. The latter implies that estimates based on migration intentions may be biased relative to estimates based on realized migration if there are systematic differences between persons realizing their move and those not realizing it. Previous research on migration intentions has shown that while only a part of intended migration is realized,Footnote 7 migration intentions are a good predictor of actual migration (De Jong et al. 1985; Fuller et al. 1985; Lu 1998; Kan 1999; De Jong 2000; Kley 2011; Van Dalen and Henkens 2013; Docquier et al. 2014; Tjaden et al. 2019) and are also driven by the same determinants as actual migration decisions (Huber and Nowotny 2013). This is also reflected in our data, as can be seen from the top panel of Fig. 1. This plots the share of respondents willing to migrate abroad at the country level against the number of co-nationals residing abroad in 2010 (as given by the United Nations 2017) relative to the population of the respective sending country. It shows that the average willingness to migrate abroad is significantly positively correlated (with a correlation coefficient of 0.371) with past migration behavior.

Share of respondents willing to migrate abroad vs. share of population living abroad (top) and vs. share of respondents willing to migrate internally (bottom). Source: Life in Transition Survey 2010, United Nations (2017), own calculations. Standard errors in parentheses

The bottom panel of Fig. 1, by contrast, shows that the share of respondents willing to migrate abroad is also strongly correlated with the share of those willing to migrate internally (coefficient of correlation: 0.77). In addition, the share of respondents willing to migrate abroad and within a country exhibits substantial variation across countries. In accordance with the findings of previous literature (see e.g., Fidrmuc 2004; Andrienko and Guriev 2004; Fouarge and Ester 2008; Paci et al. 2010), the willingness to migrate abroad and internally is highest in former Yugoslavian and lowest among former Soviet Union countries. The highest share of persons willing to migrate neither within a country nor abroad is found in Tajikistan (with 82.2% of the respondents) followed by Uzbekistan (79.8%). The lowest share of such persons is found in Mongolia (44.0%) followed by Macedonia (45.8%). The willingness to migrate both abroad or internally is highest in Macedonia (with 33.3% of the respondents) and lowest in Tajikistan (only 6.4%). The share of people willing to move only within the country is again highest in Mongolia (with 19.9%) but lowest in Tajikistan (3.9%), while the share of those willing to migrate abroad only is highest in Moldova (17.0%) and lowest in the Czech Republic (with 2.5%) (see Table 9 in the appendix).

3.2 Key independent and control variables

According to the theoretical model, the key independent variables in our analysis are the individual risk aversion of the respondents and the country risk measure. To measure individual risk aversion, we use the answers to a question asking respondents to rate their general willingness to take risks on a scale from 1 to 10. The question used in the LITS is an almost literal translation of a similar question in the German socioeconomic panel, which has also been used by Jaeger et al. (2010) and was shown to have a high behavioral validity by Dohmen et al. (2011). The response to this question was therefore used to construct a risk aversion indicator by rescaling the variable such that 10 indicates the highest possible risk aversion and 1 the least risk averse response.

To measure sending country-specific risks, we merge the interview-based data with country level risk measures provided by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) on its website. This consists of assessments of ten country level risk dimensions (security, political stability, government effectiveness, legal and regulatory, macroeconomic, trade and payments, financial, tax policy, labor market, and infrastructure risks) derived from 70 quantitative and qualitative indicators and subsequently aggregated to an overall risk score. All risk measures vary between 0 and 100, with higher numbers indicating a riskier environment (see Economist Intelligence Unit 2017, for details). The overall risk score thus provides information on an encompassing set of risk indicators and will be used as the main country-level risk indicator. The ten risk dimensions will be used to provide a more detailed analysis as to which risks are particularly relevant for migrants.

Figure 2 in its top panel shows the distribution of individual risk aversion while the bottom panel shows the between-country distribution of the overall risk indicator. Consistent with the previous literature (e.g., Dohmen et al. 2011), we find a large variance in risk aversion across individuals with most of the respondents reporting an intermediate level of risk aversion. In addition, as also found by Dohmen et al. (2011), very few respondents (5.7%) report to be very willing to take risks but quite a few (14.2%) report not to be willing to take risks at all. The distribution of risk aversion is thus left skewed and—as shown in Fig. 7 in the appendix—relatively similar across countries.Footnote 8 Nevertheless, countries whose respondents exhibit higher average risk aversion also tend to have lower shares of respondents willing to migrate within their respective country and abroad (see Fig. 3) as the average risk aversion by county is significantly (at the 5% confidence level) and negatively correlated with both the willingness to migrate internally and abroad (with correlation coefficients of -0.39 and -0.45).Footnote 9 There is also substantial variation in the overall risk measure across countries in our sample. The lowest overall risk measure is reported for Slovenia (with a score of 24) and the highest for Uzbekistan (with a score of 74), with the modal country reaching a score of 50 to 60 points.

Finally, the questionnaire also contains several control variables which can be used to measure individual-level factors impacting on income opportunities and migration costs (i.e., \( {\mu}_a^i-{\mu}_h^i \), \( {\mu}_e^i-{\mu}_h^i \), \( {\overline{c}}_e \) and \( {\overline{c}}_a \) in Eqs. 1 and 2). We consider two specifications. The first (reduced) specification controls only for terms usually included in standard Mincer earnings equations (i.e., age, age squared, and dummy variables for educational attainment) and gender to account for individual-level income opportunities. It also includes proxies for migration costs by including dummy variables for persons who are married or have children, which can be expected to have higher psychological migration costs. The second (extended) specification, which is our preferred model, additionally controls for household size, the number of years a respondent has been living in her village of residence and includes dummy variables for home ownership, unemployment, belonging to a religious or linguistic minority,Footnote 10 living in an urban environment, and the quantile of the home country’s wealth distribution a respondents consider herself to be in. Furthermore, it includes proxy variables for social capital (i.e., generalized trust and the number of memberships in voluntary organizations). These variables have been shown to be correlated with both risk aversion and the willingness to migrate in previous literature (e.g., Faggian et al. 2007; Bonin et al. 2009; Dohmen et al. 2011, 2016).

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the overall sample (in the first block) and for the subsamples of persons who state that they would be (i) willing to migrate neither abroad nor to another region of the country (second block), which applies to 63.8% of the sample, (ii) only willing to migrate internally (block three, 7.6% of the sample), (iii) only willing to migrate abroad (block four, 8.3% of the sample), or (iv) willing to migrate both abroad and internally (block five, 20.3%). Consistent with our hypotheses, respondents that are willing to migrate neither abroad nor internally are on average most risk averse, followed by persons only willing to migrate internally and those only willing to migrate abroad. Those willing to move both abroad and internally are the least risk averse.

Differences between groups can also be found for the control variables. For example, persons who are willing to migrate neither abroad nor internally are on average older, more often female, married, and are, despite being the least well-educated, less often unemployed. Being older, they also have the highest average years of residence in the same village among all subgroups and are more likely to own a home. Persons that are both willing to migrate abroad and internally are the youngest, least often married, and have resided in the same village for the shortest time among all subgroups. They show the highest proportion of unemployed members and religious minorities. Persons willing to migrate only abroad or only within the country mostly fall between these two groups.

4 Estimation strategy

Descriptive statistics thus provide some evidence for a significant relationship between risk aversion and mobility intentions. To analyze whether these patterns prevail even after controlling for other individual characteristics, we build on Eqs. (1) and (2) and define the index functions:

and

Equations (3) and (4) empirically represent the willingness to migrate internally or abroad. If \( {\eta}_e^i \) and \( {\eta}_a^i \) are normally distributed, the probabilities of being willing to migrate within the home country or abroad given the explanatory variables \( {X}_k^i \), \( \Pr \left( WT{M}_e^i=1|{X}_e^i\right) \) and \( \Pr \left( WT{M}_a^i=1|{X}_a^i\right) \), can be estimated using probit models:

using individual-level risk aversion as a measure of αi and the interaction between individual-level risk aversion and the overall country risk to test the hypothesis that the impact of risk aversion depends on the level of risk in the sending country. \( {Z}_e^i \) and \( {Z}_a^i \) include all control variables discussed in the previous section and a full set of country fixed effects. These control for all sending country-specific variables (e.g., GDP per capita, [un]employment rates, the share of persons from this country already living abroad, country size or the degree of urbanization, and the level of overall risk). Furthermore, these fixed effects absorb sending country-specific differences in destination countries (for instance, GDP per capita in the most important destination countries of previous migrants from this sending country).

Since both \( WT{M}_e^i \) and \( WT{M}_a^i \) are always observed, the coefficients in (5) and (6) could consistently be estimated from separate probit regressions. But if the error terms \( {\eta}_e^i \) and \( {\eta}_a^i \) are correlated and follow a bivariate normal distribution with zero mean and correlation coefficient ρ (see Greene 2012, p. 738 or Cameron and Trivedi 2005, p. 522 for details), such that:

It is more efficient to estimate the equations jointly using a bivariate probit model (De Luca 2008, p. 192).

One advantage of this model is that it takes into account (and allows for an estimation of) the correlation between the error terms of the two equations: If ρ > 0 (ρ < 0), unobserved factors increasing the willingness to migrate internally also increase (decrease) the willingness to migrate abroad. This suggests that the decisions to migrate internally and externally are positively (negatively) related even after controlling for observable characteristics. If ρ = 0, the bivariate probit collapses to two separate probits; whether this is the case can be tested empirically. Furthermore, using the bivariate probit, it is possible to calculate not only the marginal effects of explanatory variables on \( \Pr \left( WT{M}_e^i=1|{X}_e^i\right) \) and \( \Pr \left( WT{M}_a^i=1|{X}_a^i\right) \), but also the marginal effects on the probabilities of all four outcome combinations that arise from our two binary dependent variables: the probability of being willing to migrate neither abroad nor internally (\( WT{M}_e^i=0\wedge WT{M}_a^i=0 \)), being willing to migrate within the country only (\( WT{M}_e^i=1\wedge WT{M}_a^i=0 \)), being willing to migrate abroad only (\( WT{M}_e^i=0\wedge WT{M}_a^i=1 \)), and being willing to migrate both abroad and internally (\( WT{M}_e^i=1\wedge WT{M}_a^i=1 \)). Finally, as noted by Greene (Greene 2012, p. 743, see also De Luca 2008, p. 192), “there is no requirement that different variables appear in the equations, nor that a variable be excluded from each equation.” Therefore no a priori restrictions on the set of variables included in \( {Z}_e^i \) and \( {Z}_a^i \) have to be imposed, and the same control variables can be used in both equations. This ensures that one can “let the data speak” as to which variables are important determinants for these outcomes.

5 Results

5.1 Estimation results

The results of the bivariate probit estimates of Eqs. (5) and (6) in Table 2 are highly consistent with the theoretical and empirical model. They also suggest a strong and positive relationship between the unobserved components affecting the willingness to migrate within a country (\( {\eta}_e^i \)) and abroad (\( {\eta}_a^i \)). The estimated correlation coefficient (ρ) between these components is 0.8 and statistically significant at the 1% level in both specifications. In addition, χ2-tests firmly reject the null hypothesis that the estimated parameter vectors on the willingness to migrate abroad and the willingness to migrate internally are equivalent (with p-values below 0.001% in both specifications). This justifies the use of the bivariate probit model, since stochastic migration costs within the country and abroad are highly correlated. It also lends empirical support to treating the willingness to migrate abroad and within the country as distinct dependent variables. Further, the results indicate a highly significant negative impact of individual-level risk aversion on both the willingness to migrate abroad and internally that, as evidenced by the statistically significant coefficient on the interaction term between the country risk measure and the individual-level risk aversion indicator, is moderated by higher country-specific risks.

The effects of the control variables also accord with expectations and mirror the findings in the literature on the determinants of realized migration within and across countries. Older and married persons as well as persons with children are less willing to migrate abroad and internally. After controlling for these variables, however, household size has no further statistically significant impact on either of these outcomes. Men are more likely to be willing to migrate abroad and within the country and the willingness to migrate increases with education. Consistent with the literature arguing for a negative correlation between homeownership and mobility (e.g., Coulson and Fisher 2009) and the literature on the duration dependence of immobility (e.g., Fischer and Malmberg 2001), homeowners and persons who have resided in the same village for longer are less likely to be willing to migrate, as are individuals with higher self-assessed wealth levels. Unemployed persons, by contrast, are more likely to be willing to migrate abroad as well as within a country.

Persons with a higher level of generalized trust, an important output component of local social capital (see Durlauf and Fafchamps 2005), are also less willing to migrate abroad and internally, while the number of voluntary organizations a person is a member of as a proxy measure of globally transferable social capital (see Huber and Mikula 2019, or Fidrmuc and Gërxhani 2008) is positively correlated to both the willingness to migrate abroad and internally. This is consistent with results of David et al. (2010) who emphasize the differential impact of these measures of social capital on realized migration in EU countries. Almost all variables have the same sign and are statistically significant in both equations. The only differences are the household size variable, which is never significant, as well as the dummy variables for members of a religious or linguistic minority and residents of urban locations. Members of a religious minority and urban residents are more likely to be willing to migrate abroad (but not within the country), and members of linguistic minorities are less likely to be willing to migrate internally (but not abroad).

5.2 Marginal effects

To better assess the size of the effects, the first four columns of Table 3 report the estimated marginal effects at the mean of all independent variables on the four outcome combinations defined by our two binary dependent variables. A one-point increase in risk aversion increases the probability that a person is unwilling to move by 3.7 percentage points (pp). The marginal effects also reveal that risk aversion has a negative effect on all three mobility combinations, although the marginal effect on the willingness to migrate both within the country and abroad is strongest (−2.6 pp). This suggests that risk aversion is a larger impediment to migration for those that are prepared to consider a broader range of potential destinations. The last two columns of Table 3 report the marginal effects of the explanatory variables on the marginal probabilities of being willing to migrate internally and abroad that correspond to the choices outlined in Eqs. (1) and (2). As hypothesized, the individual-level risk aversion and overall sending country risk have a sizeable and statistically significant negative effect on both the willingness to migrate abroad and within the country. A one-unit increase in risk aversion reduces the probability to be willing to migrate within a country by 2.9 pp and the willingness to migrate abroad by 3.4 pp. A one-point increase in the overall country risk increases the willingness to migrate abroad and the willingness to migrate internally by 0.3 percentage points each. While this appears to be a small effect, a one standard deviation rise in overall risk (13.6 points) would increase the probability of being willing to migrate internally (all other variables held at their respective means) by 4.0 pp and the willingness to migrate abroad by 3.5 pp.

To illustrate the effect of the interaction of risk aversion and overall country risk, Fig. 4 plots the marginal effects of individual-level risk aversion on the willingness to migrate internally and abroad (and the 5% confidence intervals) for all possible values of overall country risk. As predicted by theory, the negative impact of risk aversion on the willingness to migrate decreases with overall country risk: In the country with the lowest observed overall country risk (Slovenia, with a score of 24), a one-unit increase in risk aversion significantly reduces the probability to migrate internally by 3.5 pp and the probability to migrate abroad by 3.9 pp. In the country with the highest observed overall country risk (Uzbekistan, with a score of 74), a one-unit increase in risk aversion reduces the average willingness to migrate internally by 2.0 pp and the willingness to migrate abroad by 2.6 pp.

Figure 4 also shows that the marginal effect of risk aversion is stronger on the willingness to migrate abroad than on the willingness to migrate within a country. This difference is statistically different from zero (at the 5% significance level) for all overall risk values lower than 88. Since the highest observed overall risk level is 74, the marginal effect of risk aversion is thus stronger on the willingness to migrate abroad than on the willingness to migrate within the country for all observed values of overall country risk. Nonetheless, country level risk also moderates the negative impact of risk aversion on the willingness to migrate internally. This is somewhat surprising given that we measure overall country risk at a national level. One potential explanation for this is that some risks (e.g., political and security risks) are localized and in addition—as evidenced by the literature on regional development in transition (see Huber 2006, for a survey)—economic risks often differ substantially between the capital cities and the remainder of the country in the transition countries we consider.

Finally, Fig. 5 provides another way to illustrate the relationship between individual risk aversion and country risk by plotting “iso-probability” lines, i.e., combinations of individual risk aversion and overall risk that correspond to the same probability of being willing to migrate. As can be seen from Fig. 5, these iso-probability lines are upward sloping: a given probability of being willing to migrate that would only be reached by persons with very low levels of risk aversion in a relatively secure country will also be reached by persons with higher levels of risk aversion if they live in a relatively risky country. This implies that persons with very different levels of risk aversion may self-select into migration depending on the level of country risks. While in low-risk countries only the least risk averse may be willing to migrate, in riskier countries even relatively risk averse persons may consider migration.

5.3 Multinomial probit estimation

As an alternative to the bivariate probit, we also estimate a multinomial probit model in which the choices are encoded as unwilling to migrate abroad and with the country (1), only willing to migrate internally (2), only willing to migrate abroad (3), and willing to migrate abroad and internally (4). This model is not as closely linked to our theoretical model as the bivariate probit and also does not allow us to identify the correlation between the choices. It, however, provides for a more direct analysis of the differences and communalities between the four types of migrants defined in the questions we analyze. Just like the bivariate probit model, it allows us to calculate the marginal effects on the probabilities of all four outcome combinations that can arise from our two binary dependent variables: the probability of being willing to migrate neither abroad nor internally, being willing to migrate internally only, being willing to migrate abroad only, and being willing to migrate both abroad and internally. In consequence, it provides an opportunity to test whether the choice of estimation method impacts our results.

Table 4 shows the coefficients and Table 5 the marginal effects estimated from the multinomial probit model. Table 5 also reports two combinations of marginal effects. The first combines the marginal effect on the willingness to migrate only internally and the marginal effect on the willingness to migrate either internally or abroad. This thus yields the marginal effect on the unconditional willingness to migrate internally. The second combines the marginal effect on the willingness to migrate abroad and the marginal effect on the willingness to migrate either internally or externally. This yields the marginal effect on the unconditional willingness to migrate abroad.Footnote 11 In this way, the results in Table 5 are directly comparable with those of the bivariate probit model in Table 3.

The results with respect to the two combined unconditional marginal effects representing the choices laid out in Eqs. (1) and (2) are virtually indistinguishable between the two models. Differences between the bivariate and multinomial probit in the estimated marginal effects on the unconditional willingness to migrate internally or the willingness to migrate abroad are in the range of −0.3 to +0.3 pp, and thus neither of statistical nor of practical significance. The same applies to the marginal effects of individual-level risk aversion and country level risk on the four individual choice categories. Here the differences amount to 0.1 pp at most, although the marginal effect of overall country risk is no longer statistically significant for the probability of only being willing to migrate internally. The only variables for which changes are slightly larger (primarily for the choices of exclusively being willing to migrate abroad or within the country) are some of the control variables such as the dummies for educational attainment, unemployment, wealth assessment, or living in an urban region. However, even if significance levels and effect sizes differ, there is no change in the sign of significant marginal effects compared with the bivariate probit. The only exception is the marginal effect of the number of years of residence on the willingness to exclusively migrate abroad.

6 Robustness

To further gauge the robustness of these results, we conducted several additional robustness checks. First, we considered the interaction between individual risk aversion and the different risk categories provided in the EIU data. Figure 6 therefore reports the results of ten regressions in which the overall country risk measure is replaced by one of the ten individual risk dimensions one at a time.Footnote 12 In these figures, the steepness of the increase in marginal effects of risk aversion with the respective risk dimension provides a measure of the intensity with which more risk averse potential migrants dislike the respective risk. Accordingly, the increase of the marginal effect of risk aversion for both the willingness to migrate abroad and within the country is strongest for labor market and security risks, while for tax policy, legal and regulatory risks, and macroeconomic risks, these are essentially flat when taking the confidence intervals into account. For all other risks, the increases resemble those of the overall risk measure. This suggests that potential migrants are particularly concerned about the security and labor market risks in their country of residence and less so about tax policy, legal, regulatory, and macroeconomic risks.

Further, we used three alternative measures of risk aversion provided in the LITS data.Footnote 13 The first of these is derived from a question in which respondents were asked whether they would prefer a safe long-term job with an average salary and few chances of promotion to a job with an above average salary and good chances of promotion, but lower job security. This is a less reliable measure of risk aversion than our preferred one, because the two jobs differ in average wages and the reference to future job stability links risk aversion and time preferences. Nonetheless, persons preferring a safe job with an average salary and few chances of promotion should be more risk averse than persons choosing the unsafe job with an above average salary and good chances of promotion. We therefore use a dummy variable taking on the value of 1 if respondents prefer the first over the second job (and zero else) as an alternative risk measure. The results of model (1) in Table 6 corroborate our previous findings. Although the coefficient sizes and marginal effects of these variables are incomparable due to the different measurements used, they imply a negative impact of risk aversion on the willingness to migrate both abroad and within the country that is moderated by overall sending country risk.

Models (2) and (3) in Table 6 use a risk indicator instead of the risk aversion variable. The first risk indicator is defined in analogy to Jaeger et al. (2010) by taking on the value one if risk aversion is between 6 and 10, and zero if it is between 1 and 5. The alternative risk indicator equals one if the respondent’s risk aversion is equal to or higher than the median risk aversion in the respondent’s country of residence (zero else), to account for potential country-specific differences in risk assessment that could, for example, be related to cultural differences. Again, we find a significantly negative effect of risk aversion on the willingness to migrate internally and abroad that is moderated by overall country risk. Furthermore, the difference between models (2) and (3) in Table 6 is negligible, which suggests that the risk indicator that accounts for country-specific differences in risk attitudes is not necessarily superior to the indicator that does not (although the former spots slightly lower AIC and BIC values).

Another concern that could be raised is that by 2010, when the LITS survey was conducted, citizens of the transition countries under consideration may already have had enough time to migrate if they wished to do so.Footnote 14 This could imply that the current paper analyzes the willingness to migrate of persons who, by revealed preference, never migrated. We thus restricted our sample to 16- to 25-year-old respondents, who are less likely to have had the possibility to emigrate previously or have had this possibility for a shorter period of time. Furthermore, since our data focuses on intended rather than realized migration, information on the potential receiving countries of the migration flows cannot be included. This implies that we also cannot control for the riskiness of the receiving country or region, although this should play a role according to our theoretical model. We therefore constructed a proxy measure for average receiving country risksFootnote 15 and included this (interacted with the individual risk aversion) as an additional explanatory variable to the analysis.

The results of Table 7 accord with previous findings. Model (1), which focuses only on 16- to 25-year-old respondents, reveals a slightly stronger negative impact of risk aversion on both the willingness to migrate abroad and internally and a slightly higher estimate of the interaction term between individual-level risk aversion and overall country risk. It, however, leaves the overall qualitative findings of the paper unchanged.Footnote 16 By contrast, model (2) shows that the interaction of individual risk aversion with our proxy for receiving country risks enters the regression with a coefficient that is not statistically different from zero, leaving the estimation results essentially unchanged.Footnote 17

Finally, in a last robustness check, we use alternative measures of the willingness to migrate. These are derived from questions in which respondents were first asked whether they planned to move abroad in the next 12 months. Subsequently, those who answered no to this were asked whether they planned to move within the country in the next 12 months. There are, however, some drawbacks to using this indicator. One of these is that there are only few respondents (less than 8%) who plan to migrate in the next year. This implies that the responses to these questions offer less variance to be explained by the independent variables, lowering the chances to identify the effects of risk aversion on migration intentions relative to the alternative used above. Another drawback is that only the response related to the willingness to migrate abroad is consistent with the one used in the baseline analysis. The response related to the willingness to migrate within the country, by contrast, is conditional on being unwilling to migrate abroad and thus represents the willingness to migrate internally conditional on not being willing to migrate abroad (WTMe ∣ WTMa = 0) rather than the unconditional willingness to migrate (WTMe = 1) as in the main regression. Finally, unlike the questions used in the main specification, these questions do not specifically address job-related mobility intentions, but rather query general migration propensities. The responses are therefore not directly comparable. Nevertheless, we estimate the effect of risk aversion and overall country risk on these alternative mobility questions using a multinomial probit model where the dependent variable is 0 if the respondent is willing to migrate neither abroad nor within the country, 1 if she is willing to migrate abroad (and maybe also within the country), and 2 if she is willing to migrate internally given that she is unwilling to migrate abroad.

The results of this analysis (in Table 8) once more imply that risk aversion has a significantly negative effect on the intention to migrate internally and abroad in the next 12 months, with the effect being stronger on the intention to move abroad. The negative effect of risk aversion is again decreasing with overall country risk, but for those who intend to move internally, the effect is not estimated with enough precision to be statistically significant. Furthermore, most of the other effects are in line with expectations and the results from Table 2, although one has to keep in mind that the outcome categories are not directly comparable.

In sum, the robustness checks corroborate the theoretical prediction that, all else equal, more risk averse individuals are less likely to be willing to migrate abroad as well as within the country, and that risk aversion has a less negative impact on migration intentions in riskier countries.

7 Conclusions

Using a large-scale individual-level dataset covering 30 countries that account for more than 25% of worldwide migrant stocks (the Life in Transition Survey), we find a statistically significant negative impact of risk aversion on the willingness to migrate both within countries and abroad. This negative impact of risk aversion is robust across various specifications and to using alternative measures of risk aversion. Furthermore, consistent with theoretical predictions, the strength of this impact is equally robustly moderated by the sending country risk (i.e., less negative in riskier countries) and also significantly larger for the willingness to migrate abroad than the willingness to migrate within a country. In addition, the willingness to migrate within a country and abroad are highly correlated even after controlling for observable characteristics. This can be taken as evidence that similar unobserved factors affect migration costs abroad and within countries.

The results, however, also point to some stylized facts that cannot easily be accounted for by standard migration theories and that could be the focus of future research. In particular, the strength of the impact of risk aversion on migration intentions seems more strongly linked to labor market and security risks than macroeconomic risks. This may suggest that security risks are more important for the overall risk assessment of potential emigrants than are economic risks, or that the short-term nature of the latter is less relevant to (long-term) migration decisions. Furthermore, the moderating effect of country level risks on the impact of risk aversion applies to the willingness to migrate internally as well as to the willingness to migrate abroad. One potential reason for this may be that risks are localized and that the result is therefore due to the wish of potential migrants to move from riskier locations in their country of residence to less risky ones. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that immigrants seem to care particularly about labor market and security risks that are often bound to specific locations. Future research may therefore consider the impact of such localized risks on migration decisions.

Also, although our theoretical predictions should apply to all countries, our empirical results only provide evidence for transition countries. Even though these account for over a quarter of the worldwide migrant stock, future research may aim to extend the current analysis to more countries or other country groups that have been less affected by institutional and systemic change in recent years as this may have an impact on e.g., the type of risks most relevant for migration decisions. Furthermore, the use of data on migration intentions provides only limited possibilities to consider the impact of receiving country risks on migration decisions. Future research may therefore also aim to collect and analyze individual-level data on actual migration decisions to better control for receiving country characteristics.

Finally, the clear trade-off between individual risk aversion and overall country risk also has implications for receiving countries, as migrants from relatively risky countries are likely to be less strongly selected in terms of risk aversion relative to the sending country population than migrants from relatively safe countries. This may lead to these migrants being more risk averse on average than the receiving country population, which could have important implications for instance for the literature on migrant entrepreneurship and risk aversion. Future research may therefore also want to consider the impact of the self-selection of migrants on risk aversion from a receiving country perspective.

Notes

Bonin et al. (2009) also provide direct evidence on risk aversion of international migrants but compare these to natives in the destination country. They find that immigrants to Germany are more risk averse than natives.

Individuals also prefer moving abroad over moving internally if \( {\mu}_a^i-{\mu}_e^i-{\overline{c}}_a^i+{\overline{c}}_e^i-{\alpha}_i\left({\sigma_a}^2-{\sigma_e}^2\right)/2>{\eta}_a^i-{\eta}_e^i \). This condition completes the description of the individual choice set, but is not necessary to describe the stated preferences of potential migrants in the context of the data used in the current paper.

We focus on the survey’s second wave as the first and third waves contain no or incomparable questions on mobility intentions.

The wording of the questions and coding of the key dependent and independent variables are explained in detail in the data annex to this paper.

To the best of our knowledge, only Jaeger et al. (2010), in their robustness section, and Gibson and McKenzie (2011) consider the impact of risk aversion relative to the sending region’s population, while Nowotny (2014) analyzes the effect of risk aversion on migration and cross-border commuting intentions.

E.g., van Dalen and Henkens (2013) find that 34% of those willing to migrate in the near future realized this plan within 5 years in the Netherlands. Among those unwilling to migrate, only 0.5% migrated in the same period. Similarly, Kan (1999) finds that almost half (47%) of those who expected to move (but only about 9% who did not expect to move) actually migrated within the following 2 years, and Fuller et al. (1985) find that in Thailand, 52% of those who stated a preference for moving to Bangkok actually moved there during the following 2 years as compared with only 12% of those who said they would not go to Bangkok.

According to Fig. 7, in 22 out of 30 countries, the median individual risk aversion is 6, and thus equal to the overall sample median. In all but one of the remaining countries, it is either 5 or 7; only for Tajikistan, we find a higher median value of 8. The lower and upper quartiles are also strikingly similar across countries, with few exceptions, with an interquartile range of 4 in 24 of the 30 countries.

The correlation coefficient between overall country risk and average risk aversion is positive (with 0.21), but not significantly different from zero.

Survey respondents were asked for their religion and their mother tongue. Those whose religion or mother tongue does not correspond to the mode of the country they live in are coded as belonging to a religious or linguistic minority (see Appendix).

Standard errors for the combinations were calculated in the Stata software package using the SPost13 routine “mlincom”.

The full regression results are available from the authors upon request.

Additional robustness tests included estimating a seemingly unrelated linear regression model and country-by-country estimates (in an earlier versions of the paper). Their results (available from the authors upon request) were also highly consistent with the quantitative and qualitative results reported above.

Some of the countries analyzed experienced sizeable emigration during transition from a planned to a market economy.

To construct the proxy measure, we calculated the share of co-nationals living in each possible destination country of the world included in United Nations (2017) relative to the stock of all co-nationals living abroad in 2010. These shares were then used as weights to calculate the average receiving country risk using EIU data.

We also checked for potentially differential effects across the other age groups. The results suggest a statistically significantly negative impact of risk aversion on the willingness to migrate for all age groups, which is, however, most negative for the youngest, least negative for the middle age group, and between these two extremes for the oldest. Yet, differences are rather small and statistically not significant between the groups.

In this regression, Kosovo has to be excluded as it is not considered a separate country in United Nations (2017). In consequence, 780 observations for respondents from Kosovo are missing.

References

Akgüç M, Liu X, Tani M, Zimmermann KF (2016) Risk attitudes and migration. China Econ Rev 37:166–176

Andrienko Y, Guriev S (2004) Determinants of interregional mobility in Russia. Econ Transit 12(1):1–27

Bonin H, Constant A, Tatsiramos K, Zimmermann KF (2009) Native-migrant differences in risk attitudes. Appl Econ Lett 16(15):1581–1586

Borjas GJ (1991) Immigration and self-selection. In: Abowd JM, Freeman RB (eds) Immigration, trade, and the labor market. University of Chicago Press, pp 29–76

Broulíková HM, Huber P, Montag J, Sunega P (2017) Homeownership, mobility, and unemployment: evidence from housing privatization, working paper, Mendel University, Brno, Czech Republic. URL: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2896765

Cameron AC, Trivedi PK (2005) Microeconometrics. Methods and Applications, Cambridge University Press

Cojocaru A (2014) Fairness and inequality tolerance: evidence from the Life in Transition survey. J Comp Econ 42(3):590–608

Conroy HV (2009) Risk aversion, income variability, and migration in rural Mexico. California Center for Population Research, UCLA, working draft

Coulson NE, Fisher IM (2009) Housing tenure and labor market impacts: the search goes on. J Urban Econ 2009:252–264

David Q, Janiak A, Wasmer E (2010) Local social capital and geographical mobility. J Urban Econ 68(2):191–204

De Jong GF (2000) Expectations, gender, and norms in migration decision-making. Popul Stud 54(3):307–319

De Jong GF, Davis Root B, Gardner RW, Fawcett JT, Ricardo G, Abad RG (1985) Migration intentions and behavior: decision making in a rural Philippine province. Popul Environ 8(1/2):41–62

De Luca G (2008) SNP and SML estimation of univariate and bivariate binary-choice models. Stata J 8(2):190–220

Docquier F, Peri G, Ruyssen I (2014) The cross-country determinants of potential and actual migration. Int Migr Rev 48(1):S37–S99

Dohmen T, Falk A, Huffman D, Sunde U, Schupp J, Wagner GG (2011) Individual risk attitudes: measurement, determinants, and behavioral consequences. J Eur Econ Assoc 9(3):522–550

Dohmen T, Lehmann H, Pignatti N (2016) Time-varying individual risk attitudes over the Great Recession: a comparison of Germany and Ukraine. J Comp Econ 44(1):182–200

Durlauf SN, Fafchamps M (2005) Social capital. In: Aghion P, Durlauf S (eds) Handbook of economic growth, vol 1. Elsevier, pp 1639–1699

Dustmann C, Fasani F, Meng X, Minale L (2017) Risk attitudes and household migration decisions, Centro Studi Luca D’Agliano Development Studies Working Papers No 423

Economist Intelligence Unit (2017): Guide to risk briefing methodology, http://viewswire.eiu.com/index.asp?layout=RKArticleVW3&article_id=485802032 (accessed Jan 05, 2020)

Eeckhoudt L, Gollier C, Schlesinger H (2011) Economic and financial decisions under risk. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Faggian A, McCann P, Sheppard S (2007) Some evidence that women are more mobile than men: gender differences in UK graduate migration behavior. J Reg Sci 47(3):517–539

Fidrmuc J (2004) Migration and regional adjustment to asymmetric shocks in transition economies. J Comp Econ 32(2):230–247

Fidrmuc J, Gërxhani K (2008) Mind the gap! Social capital, East and West. J Comp Econ 36(2):264–286

Fischer PA, Malmberg G (2001) Settled people don’t move: on life course and (im-)mobility in Sweden. Int J Popul Geogr 7(5):357–371

Fouarge D, Ester P (2008) How willing are Europeans to migrate? A comparison of migration intentions in Western and Eastern Europe. In: Ester P, Muffels R, Schippers J, Wilthagen T (eds) Innovating European labour markets dynamics and perspectives. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 49–72

Fuller TD, Lightfoot P, Kamnuansilpa P (1985) Mobility plans and mobility behavior: convergences and divergences in Thailand. Popul Environ 8(1–2):15–40

Gibson J, McKenzie D (2011) The microeconomic determinants of emigration and return migration of the best and brightest: evidence from the Pacific. J Dev Econ 95(1):18–29

Greene WH (2012) Econometric analysis, 7th edn. Prentice Hall

Harris JR, Todaro MP (1970) Migration, unemployment and development: a two-sector analysis. Am Econ Rev 60(1):126–142

Huber P (2006) Regional labor market developments in transition, Policy Research Working Paper Series 3896, The World Bank

Huber P, Mikula S (2019) Social capital and migration intentions in post-communist countries. Empirica 46(1):31–59

Huber P, Nowotny K (2013) Moving across borders: who is willing to migrate or to commute? Reg Stud 47(9):1462–1481

Jaeger DA, Dohmen T, Falk A, Huffman D, Sunde U, Bonin H (2010) Direct evidence on risk attitudes and migration. Rev Econ Stat 92(3):684–689

Kan K (1999) Expected and unexpected residential mobility. J Urban Econ 45(1):72–96

Kley S (2011) Explaining the stages of migration within a life-course framework. Eur Sociol Rev 27(4):469–486

Lu M (1998) Analyzing migration decision making: relationships between residential satisfaction, mobility intentions, and moving behavior. Environ Plan A 30(8):1473–1495

Nikolova E, Sanfey P (2016) How much should we trust life satisfaction data? Evidence from the Life in Transition Survey. J Comp Econ 44(3):720–731

Nowotny K (2014) Cross-border commuting and migration intentions: the roles of risk aversion and time preference. Contemp Econ 8(2):137–156

Özden Ç, Parsons C, Schiff M, Walmsley TL (2011) Where on earth is everybody? The evolution of global bilateral migration, 1960-2000. World Bank Econ Rev 25(1):12–56

Paci P, Tiongson ER, Walewski M, Liwiński J (2010) Internal labour mobility in Central Europe and the Baltic Region: evidence from labour force surveys. In: Caroleo FE, Pastore F (eds) The labour market impact of the EU enlargement: a new regional geography of Europe? Springer, pp 197–225

Sjaastad LA (1962) The costs and returns of human migration. J Polit Econ 70(5):80–93

Tjaden J, Auer D, Laczko F (2019) Linking migration intentions with flows: evidence and potential use. Int Migr 57(1):36–57

United Nations (2017) Trends in international migrant stock: the 2017 revision, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, database POP/DB/MIG/Stock/Rev.2017

Van Dalen HP, Henkens K (2013) Explaining emigration intentions and behaviour in the Netherlands, 2005-10. Popul Stud 67(2):225–241

Acknowledgments

The authors thank three anonymous reviewers and the participants of the 11th Geoff Hewings workshop at the Austrian Institute of Economic Research in Vienna, Martin Guzi and Stepan Mikula for helpful comments.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Paris Lodron University of Salzburg. Peter Huber is thankful for the support of the Czech Science Foundation (grant no. 18-16111S).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Klaus F. Zimmermann

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huber, P., Nowotny, K. Risk aversion and the willingness to migrate in 30 transition countries. J Popul Econ 33, 1463–1498 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00777-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00777-3