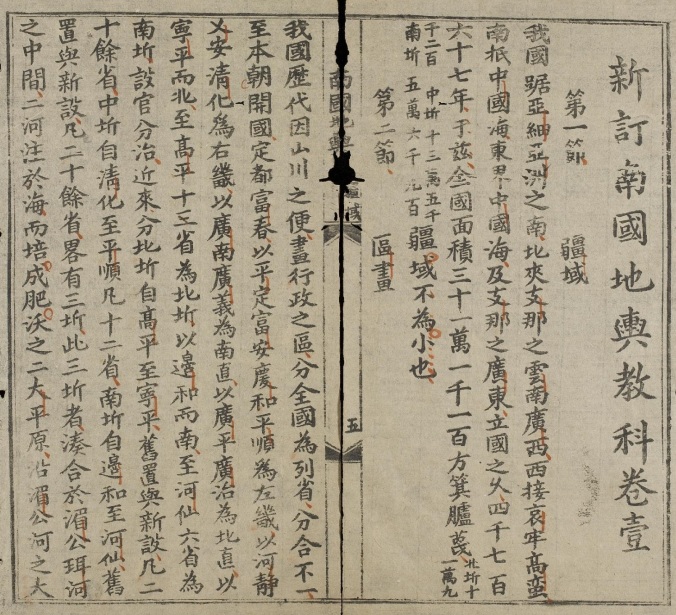

The civil service examination was of course an extremely important institution in Vietnamese history, but it is a topic that has yet to be researched in depth. Indeed, trying to understand how that institution worked is a daunting task, and it is understandable that not many scholars have tried to take on this difficult topic.

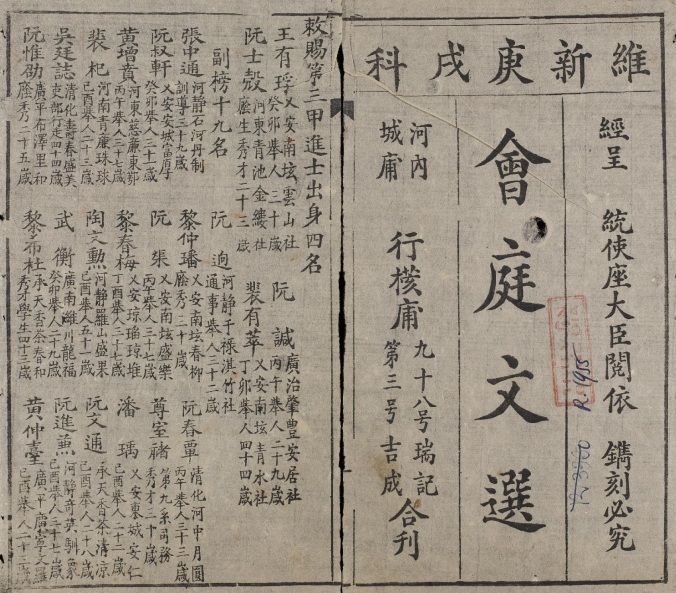

Recently I took a look at some documents that were produced in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that contain questions from the exams and “ideal answers.” Known as Selected Essays from the Palace Exam [Hội đình văn tuyển 會庭文選], these texts were meant to serve as study guides for future exam takers.

In looking at the Selected Essays from the Palace Exam from 1910, I found that there was a very interesting question and “ideal response” concerning language and writing. By 1910 there were reformist scholars in Vietnam who were encouraging people to learn the Romanized script for transcribing the Vietnamese language – quốc ngữ. The question and “ideal answer” from this exam did not support the use of quốc ngữ, nor did it support the continued use of classical Chinese. Instead, it called for the creation of a Mandarin language (quan thoại 官話) for Vietnam.

Here is the question:

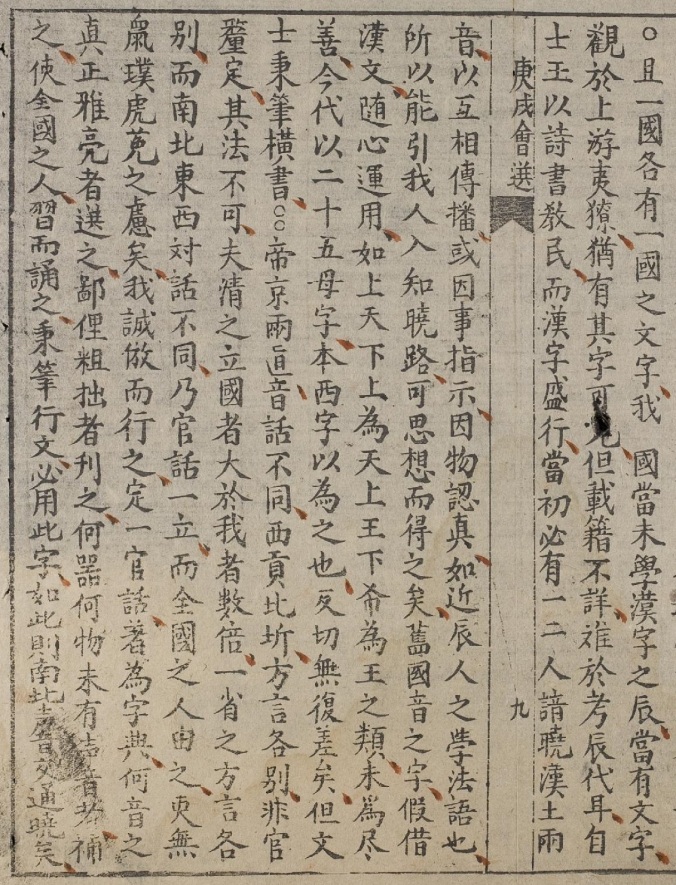

我國文字,兆自何代。士王教民漢字盛行。不知開教之始,如何而能引我人入知曉路,可思想而得之乎。舊國音之字,假借隨心,未為盡善。今代以二十五母字,反切無差。但文士秉筆橫書,方言各別,此欲南北聲音,交相通曉,亦有方法其乎。

“When did our kingdom’s writing first emerge? King Sĩ [Nhiếp, in the third century CE] taught the people, and Chinese characters flourished. When he first started teaching, I wonder how he led our people onto the road of understanding. Can this be known? The old characters based on the kingdom’s sounds were adopted following people’s preferences, and are not perfect. People of this generation use 25 letters, which are not different from fanqie [a way to use Chinese characters to represent the sounds of Chinese characters]. However, when scholars wield the brush and write, their dialects are different. To get the sounds of north and south to be mutually intelligible, is there a way to do this?”

This is a fascinating question. Essentially it is asking “how do we teach a people a new language”? Quốc ngữ was not deemed acceptable for this, because like fanqie, it simply represented sounds, and the problem was that there was no unified “sound” of Vietnamese, but instead, people in different parts of the country spoke different dialects. So how could one get Vietnamese to speak in a mutually intelligible way?

The “ideal response” to this question was that a kind of “Mandarin language” needed to be created. It appears that the person who wrote this response felt that Chinese characters would be used for this language, but that they would be linked to selected Vietnamese pronunciations and words.

Here is the answer essay in its entirety. I should note that in answering the question, the respondent was required to repeat much of the exact wording from the question, but to transform it as well. Hopefully that will be evident in the way that I have translated the answer to the question.

且一國各有一國的文字。我國當未學漢子之時,當有文字。觀於上游夷獠,猶有其文字可見,但載籍不詳,難於考時代耳。自士王以詩書教民,而漢字盛行。當初必有一二人諳曉漢土兩音,以互相傳播,或因事指示,因物認真,如近時人之學法語也,所以能引我人入知曉路,可思想而得之矣。

“Each kingdom has its own writing. Before [people in] our kingdom studied Chinese characters there must have already been writing. If you look among the upriver Lao barbarians, writing can still be seen, but the records are incomplete, and it is difficult to attribute [that writing] to a given age.

“It is from the time that King Sĩ taught our people with the [Classic of] Documents and the [Classic of] Poetry that Chinese characters flourished. At first there must have been one or two people who understand both the sounds of Chinese and the local language so that information could be transmitted, or so that events could be explained or objects identified, just like the people who presently study French are able to lead our people onto the path of understanding, so this can be known.

舊國音之字,假借漢文,隨心運用,如上天下上為天,上王下布為王之類,未為盡善。今代以二十五母字,本西字以爲之也,反切無復差矣。但文士秉筆橫書 帝京兩直,音話不通,西貢北圻,方言各別,非官釐定,其法不可。

“The old characters based on the kingdom’s sounds were adopted from Chinese writing following people’s preferences and were put to use, such as placing [the character for] ‘heaven’ [thiên 天] above [the character for] ‘above’ [thượng 上] to create [the character for] ‘heaven’ [trời 𡗶] and placing [the character for] ‘king’ [vương 王] above [the character for] ‘cloth’ [bố 布] to create [the character for] ‘king’ [vua 𤤰]. This is not perfect.

“People of this generation use 25 letters. These were originally Western characters. They are not at all different from fanqie.

“However, when scholars wield the brush and write, the spoken languages of the imperial capital and the two guards* are mutually unintelligible, and Saigon and Bắc Kỳ have their own dialects. If officials do not regulate [the language], then there is no way [to get the sounds of north and south to be mutually intelligible].”

[*Quảng Nam and Quảng Nghĩa were known as the Southern Guard (Nam Trực 南直), and Quảng Bình and Quảng Trị were the Northern Guard (Bắc Trực 北直), that is, areas that stood guard to the north and south of the imperial capital of Huế.].

夫清之立國者大於我者數倍,一省之方言各別,而南北東西對話不同,乃官話一立,而全國之人由之,更無鼠璞虎菟之慮矣。我誠倣而行之,定一官話,著為字典,何音之真正雅亮者選之,鄙俚粗拙者刊之,何器何物未有聲音者,補之,使全國之人,習而誦之,秉筆行文,必用此字,如此則南北聲音交通曉矣。

“The kingdom that the Qing established is many times larger than ours, each province has its own separate dialect, and the spoken languages of the north, south, east and west are different. But with the establishment of a Mandarin language [guanhua 官話, literally “the language of the officials”], and all of the people in the kingdom following it, there is no longer a worry of misunderstanding each other [there are classical allusions here about misunderstanding words].

“We should sincerely emulate and carry out this [practice]: establish a Mandarin language; compile a dictionary by choosing the sounds that are proper and elegant and eliminating the sounds that are coarse and vulgar; provide a sound for whatever item or object is lacking one; get all of the people in the kingdom to study and recite [the terms in the dictionary]. And when [scholars] wield the brush and write, they must use these characters, and that way the sounds of the south and north will become mutually intelligible.”

Some contributions to this article .

I’m neither linguist nor philologist ,I just have some piecemal knowledge of Chinese characters and VN matters .

_ each region in China and VN has its local dialect , called vernacular languages ; mandarin language is what’s called a vehicular lingo or lingua franca , China’s one , it’s reading Chinese characters with Pekin accent .

Mandarin was chosen as vehicular language ; so Chinese from diffferent regions to understand each other must learn and talk Mandarin also called putonghua 普通話 or guóyǔ_ quốc ngữ 國語

_ about written language , formerly was only used for administrative purposes wenyan _ văn ngôn 文 言 , an abtruse written language known only to literati . After the fall of the Ching dynasty , it was decided to abolish wenyan and to write as in the West in prosa and to write it following the common people ‘s everyday talk which is called baihua _ bạch thoại 白話

_ so each chinese and VN region has a different way of reading chinese characters and different plain talks ( or baihua )

_ quốc ngữ in VN has a different meaning , as far as I know : it is the equivalent of baihua _ bạch thoại 白話

_ Vietnamese vocabulary has two components : Han words transcriptible by Han characters and aboriginal or nôm words transcriptible by nôm characters ; nôm characters are fabricated from han characters and are not listed in Han characters dictionaries . Examples of fabrication are listed above [ ‘heaven’ [thiên 天] above [the character for] ‘above’ [thượng 上] to create [the character for] ‘heaven’ [trời 𡗶] ; placing [the character for] ‘king’ [vương 王] above [the character for] ‘cloth’ [bố 布] to create [the character for] ‘king’ [vua 𤤰]]

_ In Vn , wenyan was written only in Han characters .

_ chữ quốc ngữ is the phonetic transcription ( through latin alphabet ) supposedly only of quốc ngữ ; it’s a misnomer because it transcripts not only vernacular quốc ngữ but also wenyan writings

In the above article , the question asked in the examination should be ” should we replace Han characters by chữ quốc ngữ ‘ ?( and not by quốc ngữ )

_ in VN , to understand each other , VN from diffferent regions informally use, I surmise , northern accent _ tiếng Bắc which seemingly has not been decreed to be the vehicular VN language

“After the fall of the Ching dynasty , it was decided to abolish wenyan and to write as in the West in prosa and to write it following the common people ‘s everyday talk which is called baihua _ Bai 白話”

Yes, but “Baihua” was developed from “guanhua,” the language of the officials at the capital. So it was not really “the common people’s talk,” but instead was the way that the elite in Beijing spoke. Over the past century “baihua” has been taught to “the common people” across China, and a lot of the classical terminology that was in early “baihua” has fallen out of use.

In Vietnam there was no equivalent process of developing a common language based on the language of the capital until after 1975.

The question and answer in this essay are not about replacing chu Han with chu Quoc Ngu. That is why it is so interesting to see what they were talking about here!!! The question and answer is about how to make the various ways that people in Vietnam speak mutually intelligible.

The answer makes it clear that Quoc Ngu is not a good option, because like fanqie it records “sounds.” The problem is that the “sounds” that people produce across the country differ, and that makes it difficult for people to understand each other.

There are a couple of classical allusions that I did not translate because they require a long explanation, but one was about 鼠璞.

鄭人謂玉未理者為璞,周人謂鼠未腊者為璞。周人懷璞,謂鄭賈曰:「欲買璞乎?」鄭賈曰:「欲之。」出其璞視之,乃鼠也,因謝不取。

Zheng people call unpolished jade “pu.” Zhou people call a mouse that has not been made into dried meat [未腊?] “pu.” A Zhou person carried a “pu” and asked to sell it to a Zheng person: “Do you want to buy my ‘pu’?” The Zheng person said “Yes.” [The Zhou person] took out the ‘pu’ and showed it. It was a mouse. [The Zheng person] declined to take it.

This is what the person who answered this question was trying to avoid, and he didn’t see chu Quoc Ngu as being capable of doing this. Instead, he wanted to create a “guanhua,” which, like the guanhua in China, would have used characters, and would have taught people the correct way to pronounce those characters.

You may think “that would be impossible, because there are ‘Vietnamese’ words for which there are no ‘Chinese’ character equivalents.” Ok, but two centuries ago there were no equivalents in East Asian languages for Western terms like economy (keizai/jingji/kinh te), university (daigaku/daxue/dai hoc), and thousands of other such terms.

Today most people who grow up learning Japanese/Chinese/Vietnamese do not see these as “foreign” words. But originally there was no equivalent for these words, and Japanese scholars used Chinese characters to create equivalents for them.

The same thing could have been done to make a “guanhua” for Vietnamese. If somewhere around 80% of the vocabulary comes from Chinese, then somewhere around 80% of the job is already done. Still, one would need to determine if characters like “一” should be pronounced nhứt or nhớt or nhất, etc. (as I’m sure you are aware, all of these variations exist in 20th century writings that use chu quoc ngu, and that is what this person was trying to avoid).

As for the other 20% of the vocabulary, there are thousands upon thousands of existing Chinese characters that could be chosen from to link those sounds with a character.

This is what this person was saying should be done, and is why he said that it would require creating a dictionary and getting people to study and “chant/recite” it, as had long been done with the Tam Tự Kinh (三字經). That is unnecessary if one chooses to use a phonetic script like chu quoc ngu.

The essay raises some puzzling interrogations :

_ what was the lingua franca when in VN sprang a second polity in the south ? how did northern , southern and central VN literati and mandarins talk with each other . Usually the victors’ lingo bcame the vehicular ; so it should be ” tiếng Nam ” after Gia long unified the country

Nowadys , I think , tiếng Bắc prevails , How come , it was adopted endly ? it became the mandarin language of VN . The problem was spontaneously resolved .

_ in everyday plain talk , only one third of vocabulary is pure Han

_ tiếng Nam and tiếng Bắc are not very dissimilar ; so in 1954 when the big migration ( Bắc Kỳ Di cư ) occurred , the people managed to understand mutually but the central dialects ( 4 Quảng and Huê’ ) are quite unintelligible to Bắc and Nam people .

_ modern VN songs must absolutely be sung in tiếng Bắc , otherwise , in tiếng nam , they sound funny , even ridiculous

_ tiếng Nam is less precise than tiếng Bắc ; an usual pun: when one says to a lady ” mời cô vào vườn với tôi “( come in my garden ) in tiếng Nam , it may be understood as “mời cô vào giường với tôi ” ( come in my bed ) : vườn and giường are similar in Nam

“What was the lingua franca among the elite in nineteenth-century Vietnam?” is, I think, the question we need to ask.

When an official who was born and raised in Saigon met an official who was born and raised in Hanoi, how did they communicate? And how did both of them communicate with officials who were born and raised in the 4 Quang and Hue?

My guess would be that they did speak a form of “quanhua/Mandarin.” The one thing that all of these people would have shared was a knowledge of classical Chinese. And although we think that classical Chinese was a “dead” language, the elite could basically speak it. This is in fact still “alive” in the Chinese world. If you watch a well-made historical drama, the actors more or less “speak” classical Chinese, as their conversations are filled with classical expressions and chengyu 成語. Vietnamese can’t do that anymore, but if you read some of the earliest writings that use chu quoc ngu you can see something similar – a “common” language that was filled with Sinitic/classical Chinese expressions and ways of communicating.

To put this in a bigger perspective, my father was educated in the late 1930s in a Jesuit high school to be able to debate in Latin, a “dead” language.

My point is that people can speak “dead” languages, and my guess would be that officials from Hanoi would speak colloquially among themselves, as would the officials from Saigon when they were with Saigon friends, etc., but when they had to talk to each other, their main option would have been to use a highly-Sinicized vocabulary and linguistic expressions from classical Chinese.

Finally, I know a scholar who argues that in the Nguyen you see more and more words appearing that come from Mandarin Chinese, as people at that time were undoubtedly reading Chinese vernacular novels, like Honglou meng and Shuihu zhuan, that ultimately served as the foundation for the development of modern Mandarin.

As such, when you think about all of this, one can see how the person who wrote this exam answer could think the way he did. From his perspective, it was conceivable to create a more vernacular language from a more classical language, as this is exactly what the Chinese were doing, and the way that the Vietnamese elite from different parts of the country communicated was probably already like this – a type of more vernacular language that was developing out of a spoken classical Chinese lingua franca.

In Mandarin Chinese, the “vernacular” was created by moving down from an elite level by incorporating some non-elite terms and expressions and by discarding some elite terms and expressions that were considered too arcane. That is what this person was arguing for as well.