An influential trial in China will be a tendentious reminder of how much — and how little — China has changed in the last three decades.

A popular saying, oft attributed to Marx [1], notes, “History repeats itself, first as tragedy and then as farce”. Marx’s intellectual heirs in Beijing can take little solace in those words as they try Madame Gu Kailai for murder in coming weeks and months in a judicial event that recalls the trial of Mao Zedong’s widow in 1980.

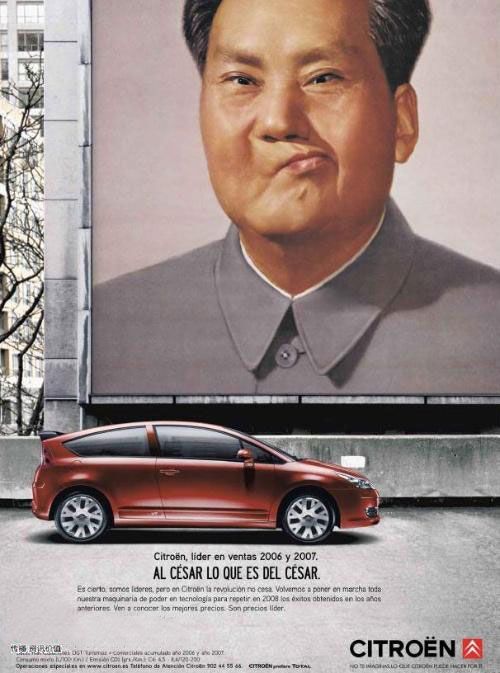

Both Gu and her husband, Bo Xilai, were the party elites, having born into highflying Communist families; the duo were more Maoist and communist than their technocratic peers in Beijing, and in their home fiefdom of Chongqing, they oversaw retro-populist, Mao-nostalgic projects. Mr. Bo had been tipped to become a senior figure in the government reshuffle later this year, before internecine struggles led to his purge and revelations that Madame Gu arranged the murder of a family confidant and her rumored lover, a British businessman named Neil Heywood last year.

Over 30 years ago, an equally imperious woman found herself in dock. The Gang of Four, led by Mao Zedong’s wife Jiang Qing, was accused of an attempted coup and of the excesses during the Cultural Revolution. For all indictments, the grisly centrepiece of the case against Madame Mao came down to a single death — that of a State Council Member Zhang Linzhi. On December 14, 1966, she had denounced Zhang, then the Minister for Coal Industry; he was later beaten to death in prison on the orders of Madame Mao, the prosecutors alleged, projecting the photos of his mangled corpse inside the courtroom (see youTube below).

Before the trial, Zhang’s death was reported as ‘suicide’ much like Heywood’s death was reported as ‘accidental overdose’ by the police. For two months, Madame Mao displayed her feisty and defiant behavior in front of 35 magistrates (all presiding simultaneously) and 880 ‘spectators’ who heckled and jeered at her. She dismissed her lawyers and defended herself, at one point memorably saying, “I was the Chairman’s dog. Whoever he asked me to bite, I bit.”

The process was televised, although the fate of Madame Mao was already fait accompli in the Chinese press; “What kind of a trial is this?” she spat. For all the reforms, progress and developments made in China three decades since, Gu’s trial underlines two things that had not changed. Firstly, she had committed this murder (and other excesses that are no doubt going to come out during the trial) because she knew that she would have gotten away protected by her husband’s aegis. This remains the prevailing attitude inside the Chinese political class. Secondly, initial covers-up of Heywood’s death suggest that this trial will be all too kangaroo. It never was a legal process arraigned not to seek out justice. It is just merely the last step in discrediting of a political opponent. That is troubling.

The great Simon Leys once wrote, “Without Mao there could have been no Madame Mao.” With the same certainty, we can say, without the Communist Party, there could have been no Madame Gu.

*

*

[1] What he actually wrote in Der achtzehnte Brumaire des Louis Bonaparte was “Hegel bemerkte irgendwo, dass alle großen weltgeschichtlichen Tatsachen und Personen sich sozusagen zweimal ereignen. Er hat vergessen, hinzuzufügen: das eine Mal alsTragödie, das andere Mal als Farce.” Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.