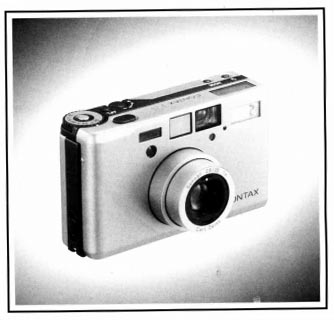

A motorized, multi-automatic, manual focus, metal built camera with a conventional user interface, the Contax ST had no real equivalent when it was launched in 1992. The Leica R7 and the Olympus OM-4ti were not motorized, and the rest of the cameras targeting the high-end of the market were auto-focus SLRs with a modal user interface.

In fact, there are very few other motorized, multi-automatic, manual focus 35mm SLRs I can think of – the most interesting of them being Canon’s T90.

In 1985, the arrival of the Minolta 7000 AF had caught the industry leaders by surprise: Minolta was the first to launch a brand new – and totally coherent – autofocus system.

At that time, Canon’s engineers were working on a top of the line manual focus camera with a revolutionary modal interface – the T90 – that was launched in 1986, and whose design and ergonomic study Canon would make to good use on their first successful autofocus SLRs, the new EOS 620 and 650, that they launched one year later.

Contax, on the other hand, did not even try its hand at an autofocus SLR until the AX of 1996 (which still used the Contax Carl Zeiss manual focus lenses), and did not launch a real 35mm autofocus camera system until Year 2000. The Contax ST of 1992 is therefore a very conventional manual focus camera.

The T90 and the ST have a lot in common – they’re positioned one step under the real professional cameras of their respective brand (the F1 and the RTS III) and boast similar characteristics: they’re large, manual focus, motorized SLRs, with a big high eye point viewfinder, with multiple auto-exposure modes and multiple metering patterns (variants of average and spot metering), LED displays in viewfinder, and they are powered by alkaline AA or AAA batteries.

Back then, and today, there are two main justifications for buying one of those cameras:

- they are high quality instruments, with a very good viewfinder, great ergonomics, and lots of control options for the photographer who wants to remain totally in charge of focusing and exposure,

- they are backed by a renown line of manual focus lenses.

There is one big drawback – of course: those systems are anchored in the past. Canon lost interest in the T90 and in the FD line of lenses as soon as the EOS hit the market, 33 years ago. The last new Contax manual focus 35mm SLR (the Aria) was released in 1998, and Kyocera has stopped providing any type of support a long time ago.

Whether you prefer the ST to the T90 comes down to lenses (the ones you own and the ones you would like to buy), ergonomic preferences, and your expectations regarding reliability.

Back then: how did the two cameras compare?

- Cost and Availability: having been launched 6 years apart, the two cameras never really competed for space on the shelves of the retailers. The T90 was manufactured for less than a year, but remained on Canon’s catalog until the launch of the EOS-1, in 1990. It was a very expensive camera – in the same price range as the Olympus OM-4ti – only professional cameras such as the Nikon F4 and of course the Leica R series were more expensive. The Contax ST became available at the end of 1992. It also had a very high list price (in the same bracket as the Canon New-F1 or the EOS-1) but cameras were heavily discounted in those days and it’s difficult to know how much people were really paying (and whether Contax cameras were more discounted than Canon’s).

- Size, Weight, Features and Ergonomics – The T90 (nicknamed the “tank” in Japan) is not that heavy after all – at 800g, its weights is the same as the ST’s (without batteries) but the Canon uses AA cells which are heavier than the AAAs of the ST. Because of its smaller dimensions (height and depth), the ST looks denser and feels heavier.

One of the best examples of “bio-design” the T90 falls naturally in the hands, with all the command easily accessible. It’s also the first example of totally modal interface (I press a key to call a menu, and I rotate the control wheel to select the setting which is shown on a large LCD display on the top plate).

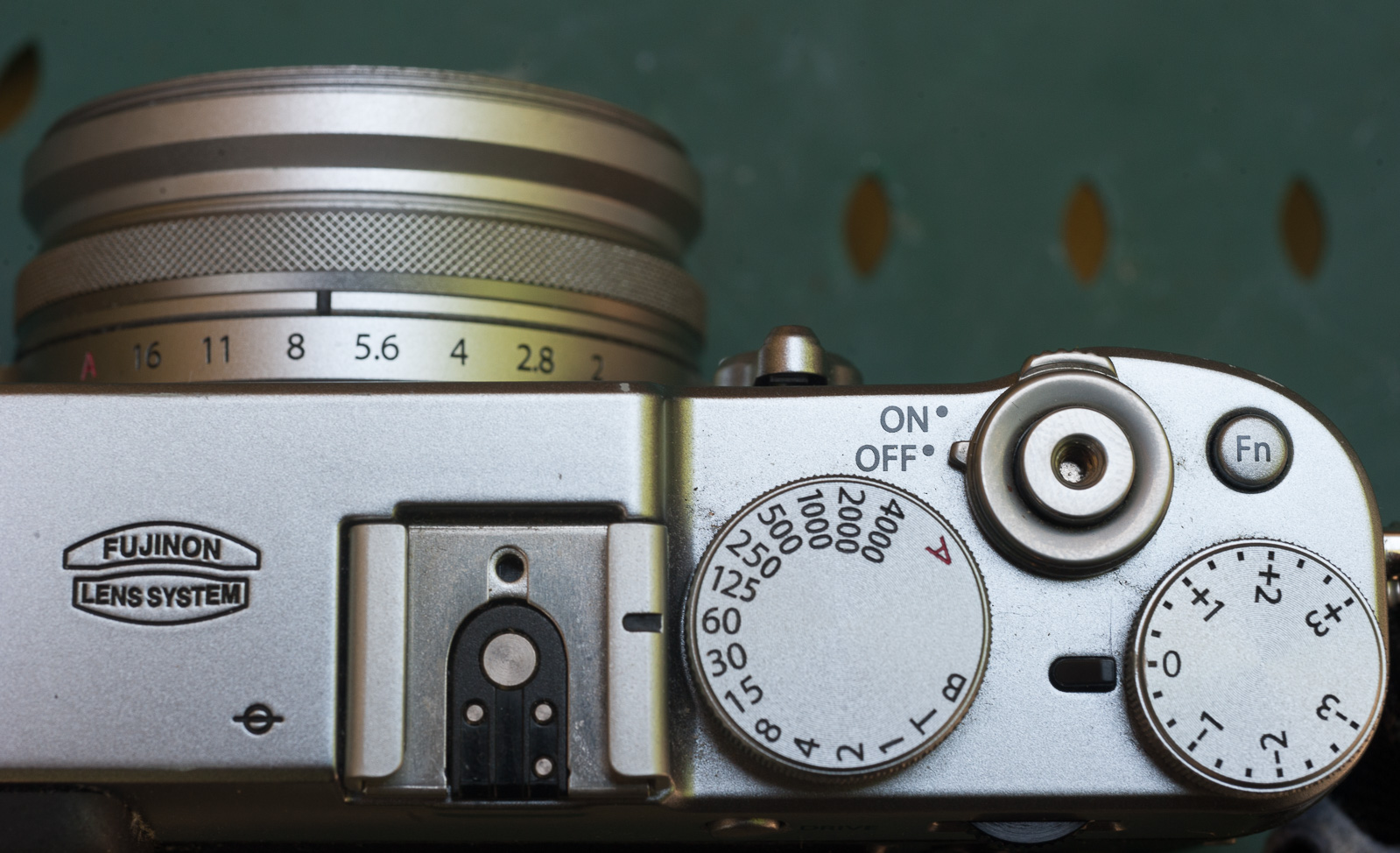

The ST offers a very conventional user interface, with one knob, one ring or one switch per command. Because the analog commands are designed to be smooth, the knobs are susceptible to changing position in the bag of the photographer, and the Contax’s commands are protected by a series of locks – it’s useful, but it slows the photographer down until the position of the locks is memorized by the muscles of the hands.

More than 30 years later, the market has still not decided which UI it likes best – Canon, Nikon and Sony are committed to the modal interface, while Fujifilm is selling cameras whose command organization is very similar to the ST’s.

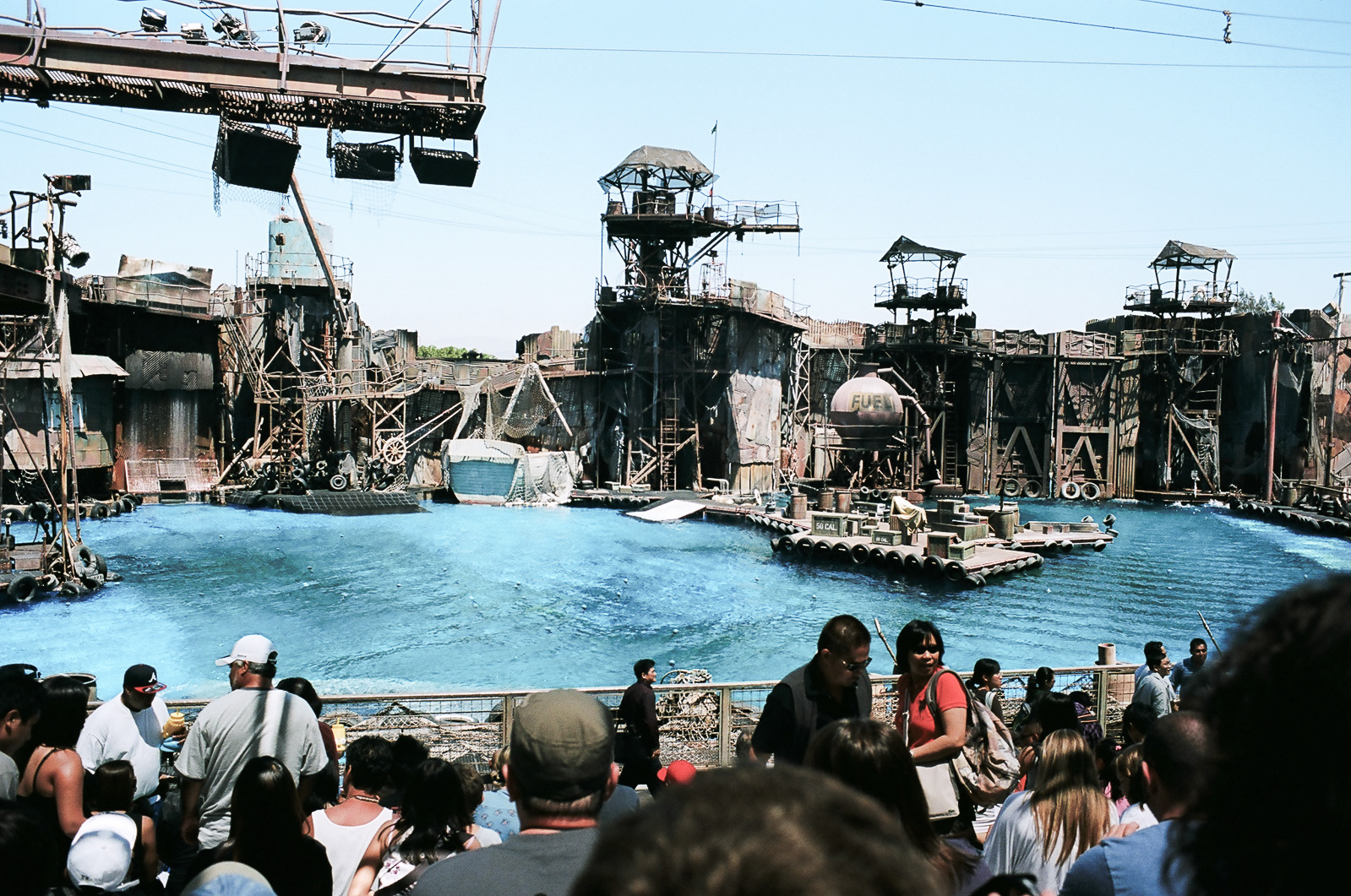

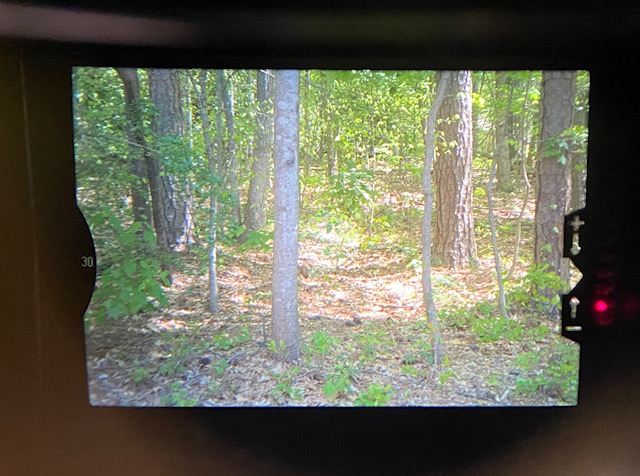

Both cameras are motorized – but not as fast as the Nikon F4 or the EOS-1 (3 frames / sec for the Contax, 4 frames / sec for the Canon). And both are loud – you can’t shoot unnoticed indoors. - Viewfinder – They’re very comparable on paper – the T90’s viewfinder covers 94% of the actual picture area, with a magnification of 0.77 and an eye point of 19mm.

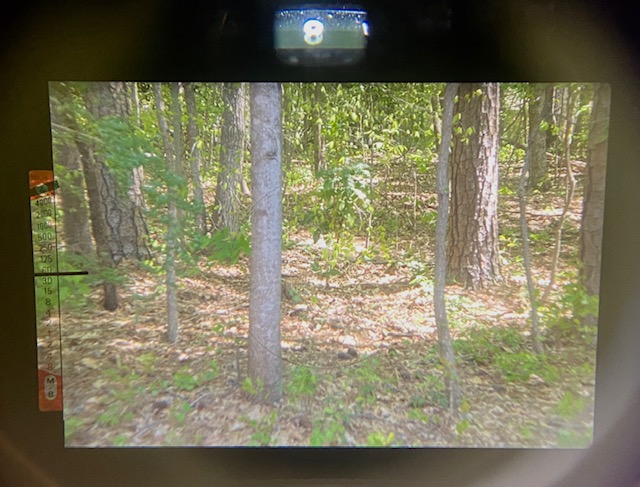

The ST’s viewfinder, on the other hand, covers 95% of the actual picture, with a magnification of 0.8. The eye point is not documented but feels longer than the T90’s.

Practically, the viewfinder of the ST is cinematic, and next to it, the T90 looks narrower, as if affected by tunnel vision.

The viewfinder screens look equally luminous (which means not as luminous as what you would find on a Nikon camera of the same era). The micro prism ring on the T90 is made of coarser elements, and is easier to the eyes than the very fine prisms of the ST, which are very difficult to see, even with the dioptric correction of the viewfinder carefully adjusted.

Both provide information at the bottom and on right side of the viewfinder – the Contax is using only red LEDs, and the T90 a combination of LEDs and of LCDs. Both viewfinders are informative, easy to read, and don’t overload the photographer with useless information. - Shutter and metering system: The T90’s shutter was the absolute best of what was available in 1986 – with a flash X sync speed of 1/250s and a top speed of 1/4000. The Contax ST offers similar performances (it can go up to 1/6000sec, but that shutter speed is not user selectable – practically, 1/4000 is the limit). The Canon T90 is probably the most complex SLR ever designed when it comes to exposure control.

First, it offers no less than four metering patterns: central weighted average, selective (a sort of ultra large spot, for the nostalgics of the Canon FTb), Spot, and last but not least, Multispot. In addition, you can also adjust the exposure for the highlights or the shadows by pushing two small buttons to change the exposure value by increments of 0.5IL. Honestly, it’s a bit too much.

The Center Weighted Average metering (the one you use for casual or travel photography) gives more importance to the sky than I wish, but because you can’t lock the exposure with the camera set for center weighted average, you have to let the camera do what it wants, and it under-exposes a bit. The Multi-Spot is gimmicky, the “Highlight and Shadows” correction is extremely powerful but very difficult to use unless you’re fluent with the theory of exposure. Lastly, only the older FL lenses offer a real semi-auto exposure mode, but you have to operate stopped down.

Compared to the T90, the ST is a model of simplicity – if offers only two metering patterns (center weighted average and spot). Like the T90, you can only lock the exposure in spot, but at least you can work with a real semi-auto mode at full aperture.

None of those cameras offer “matrix metering” – they’re definitely “old-school” in that regard.

And now

- Reliability: “the tank” may have been solidly built, but when trying to innovate with the design the camera, Canon’s engineers went a bit too far, and introduced some weaknesses. With the benefit of hindsight, some of the design decisions look outright stupid (soldering lithium batteries to the circuit board or replacing springs with magnets in the shutter, for instance). The second issue in particular impacts reliability, and it’s the reason the value of the T90 on the second hand market is so low.

The ST is not without flaws either – it seems that Contax cameras of that generation (the RTS III, ST and AX) need the aperture command lever to be re-calibrated every now and then, and the process requires access to a workshop manual and a Contax Planar F/1.4 lens. I could not find a copy of the manual workshop on the Internet so far, and having to buy a Zeiss 50mm f/1.4 lens just to be able to calibrate a camera is not a very palatable perspective (the workaround is to play with exposure compensation dial). Apart from this non trivial issue, I’ve not found or read much (positive or negative) about the Contax ST’s reliability. As far as I know, the only real troubled child of the Contax-Yashica family is the 159MM. - Scarcity: both cameras were very expensive high end machines – which limited their sales volumes – but also ensured that most of their owners did not consider them disposable, and took good care of them.

Most of the interest for the Contax cameras seems to be concentrated in Japan – I could not find any in the US and finally bought my ST on eBay from a Japanese reseller (buying from Japan is generally a very pleasant experience – the cameras are in top condition and you get yours in less than a week through the Postal Service). It’s easier to buy a T90 from a domestic reseller, even if there are only a handful on sale at any given time. And because of the potential reliability issues, I would only buy a T90 from a seller with a very good reputation, who has really tested the camera, preferably with film. - Battery: Contrarily to many autofocus SLRs of the same vintage, the T90 and the ST don’t require expensive and difficult to find single use Lithium batteries. They simply need a few AAA or AA batteries.

- Lens selection: The T90 was designed for Canon’s FD lines of lenses, but also works very well (in particular in semi-auto exposure mode) with older FL glass. Canon also sold for a while an adapter for 42mm screw mount lenses. If you add the lenses sold by third parties, the offer is limitless.

There are two issues with Canon FD lenses: the interesting ones (the luminous wide angle lenses in particular) were purchased en masse by users of Sony’s A7 series mirrorless cameras (who use them with an FD to Sony E adapter), which raised the price level on the second hand market. And since production ceased more or less with the launch of the EOS series in 1987, there are relatively few good zooms in the catalog (and in any case none of those f/2.8 constant aperture zooms preferred by the pro photographers).

Contax lenses have a great reputation – and Contax used to cover any need from the 15mm ultra-wide angle to the 600mm telephoto lens, with specialty items such as the 35mm shift lens or the medical lens also represented.

Outside of the 28, 35 or 50mm glass which sell for reasonable prices ($150.00 to $200.00), Contax branded lenses are much more expensive than Canon’s. But since Contax kept on releasing new Carl Zeiss manual focus lenses until 1998 (the last one was a compact zoom for the Aria), the lens designs are a bit more modern than with Canon, which could be good if you’re looking for a zoom.

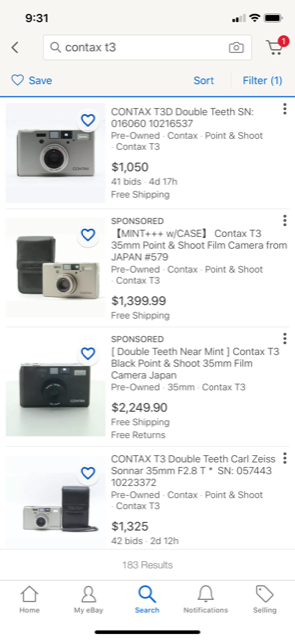

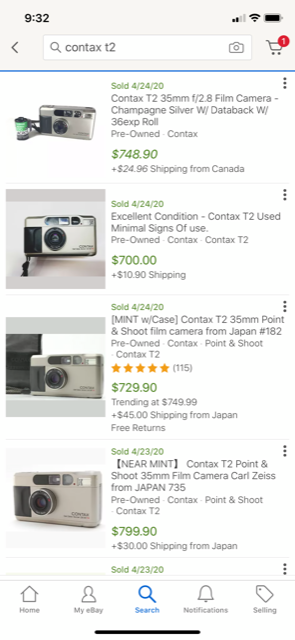

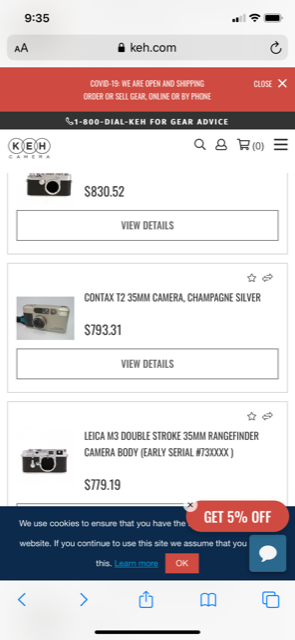

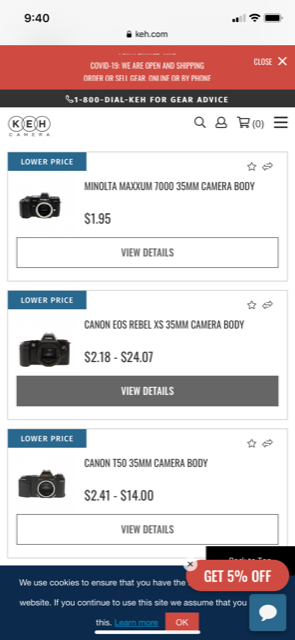

How much? Not much. Probably because of its reliability issues, the Canon T90 is not in high demand and can be found for less than $100.00; the Contax ST is also relatively cheap (approx $150 if you buy it from a Japanese reseller). In the Contax family, the S2, the RX II and the Aria are more sought after, and sell for two to four times the price of the ST.

Conclusion

The Contax ST and the T90 have a lot in common on paper, but are very different cameras in day to day use:

- ergonomics – Contax has a conventional user interface, the T90 is modal. Both are extremely pleasant to use and a photographer will enjoy working with each of them – it’s really a matter of taste.

- exposure determination – in this specific area, the Contax is more limited, but easier to use, while the Canon is much more complex and sometimes gimmicky. Honestly, none of them is a perfect fit for me: ideally, I would simply like to use the central weighted average metering with an auto-exposure lock – an option none of them offers. A matrix metering option would also have even valuable – but no manual focus Canon camera ever offered it, and Contax fans had to wait for the last manual focus SLR of the brand, the Aria, to benefit from it.

Is one of those two the ultimate manual focus 35mm SLR?

Besides the ST and the T90, there are few cameras that can legitimately compete for the distinction: a few Leica R models, the Olympus OM-4ti, a few other Contax cameras, maybe.

The Contax ST is a high quality, carefully designed and nicely built manual focus SLR for photographers who prefer their cameras full featured, but also easy to use and unobtrusive. A very nice tool. But it lacks this ounce of folly and excessiveness that graces the T90.

The Canon T90 is far from perfect – even if its limitations in the exposure department are inherited to a large extend from the FD lens mount’s shortcomings – and it has its own reliability issues. But it was a revolutionary camera in its time: there’s no manual focus SLR like it, and there’s still something magic in the simplicity of its user interface.

Interestingly, the British Contax Web site is still up: https://www.contaxcameras.co.uk/_html/index.html