Journal of Film Preservation - FIAF

Journal of Film Preservation - FIAF

Journal of Film Preservation - FIAF

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

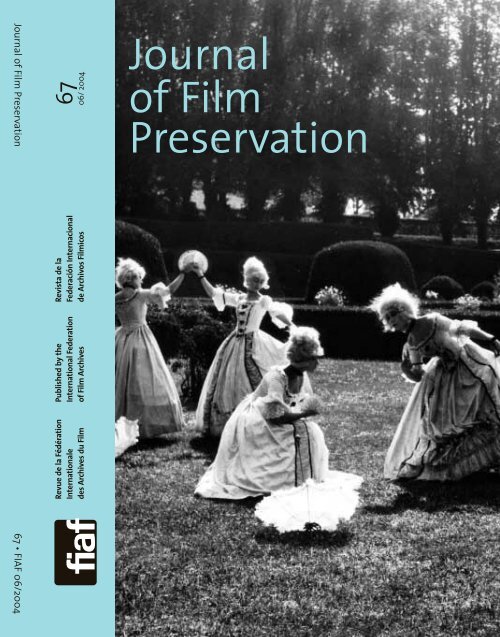

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> 67 • <strong>FIAF</strong> 06/2004<br />

67<br />

06/ 2004<br />

Revista de la<br />

Federación Internacional<br />

de Archivos Fílmicos<br />

Published by the<br />

International Federation<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> Archives<br />

Revue de la Fédération<br />

Internationale<br />

des Archives du <strong>Film</strong><br />

<strong>Journal</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong><br />

<strong>Preservation</strong>

June / juin<br />

junio 2004 67<br />

Der Var Engang,<br />

Carl T. Dreyer, 1922<br />

Courtesy <strong>of</strong> the Danish <strong>Film</strong><br />

Institute Stills & Posters Archive<br />

Open Forum<br />

2 Second Century Forum - Stockholm June 2003<br />

David Francis<br />

10 Projectionniste dans une cinémathèque : le cas de la<br />

Cinémathèque québécoise<br />

François Auger<br />

Historical Column / Chronique historique / Columna histórica<br />

15 Contribution à une histoire de la Cinémathèque française<br />

Pierre Barbin<br />

Restorations / Restaurations / Restauraciones<br />

31 The Restoration <strong>of</strong> Dreyer’s Der var engang<br />

Casper Tybjerg, Thomas C. Christensen<br />

Technical Column / Chronique technique / Columna técnica<br />

37 Biodegradation <strong>of</strong> Motion Picture <strong>Film</strong> Stocks<br />

Concepción Abrusci, Norman S. Allen, Alfonso del Amo,<br />

Michelle Edge, Ana Martín-González<br />

<strong>Film</strong> Festivals / Festivals de cinéma / Festivales de cine<br />

55 From Bologna to Sacile<br />

Antti Alanen<br />

62 L’Esprit de la ruche : 30 ans déjà<br />

Robert Daudelin

News from the Archives / Nouvelles des archives /<br />

Noticias de los archivos<br />

64 Montréal: La Beauté du geste<br />

Eric LeRoy<br />

66 Rimini: La Fondazione Federico Fellini<br />

Vittorio Boarini<br />

73 Stockholm: New Facilities at the SFI<br />

Jan-Erik Billinger, Bo Wedelfors<br />

Publications / Publications / Publicaciones<br />

75 Jean Desmet and the Early Dutch <strong>Film</strong> Trade<br />

Ivo Blom<br />

Eileen Bowser<br />

77 Opérascope<br />

Réal La Rochelle<br />

Robert Daudelin<br />

78 The Unknown Orson Welles<br />

Sous la direction de Stefan Drössler<br />

Robert Daudelin<br />

79 L’Homme au cigare<br />

Long métrage documentaire d’Andy Bausch<br />

Robert Daudelin<br />

80 Shennü: Converting a Silent Chinese Classic to DVD<br />

Richard J. Meyer<br />

82 Publications Received at the Secretariat / Publications reçues au<br />

Secrétariat / Publicaciones recibidas en el Secretariado<br />

84 <strong>FIAF</strong> Bookshop / Librairie <strong>FIAF</strong> / Librería <strong>FIAF</strong><br />

<strong>Journal</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong><br />

<strong>Preservation</strong><br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong><br />

Half-yearly / Semi-annuel<br />

ISSN 1609-2694<br />

Copyright <strong>FIAF</strong> 2004<br />

<strong>FIAF</strong> Officers<br />

President / Président<br />

Eva Orbanz<br />

Secretary General / Secrétaire général<br />

Meg Labrum<br />

Treasurer / Trésorier<br />

Karl Griep<br />

Comité de rédaction<br />

Editorial Board<br />

Chief Editor / Rédacteur en chef<br />

Robert Daudelin<br />

EB Members / Membres CR<br />

Mary Lea Bandy<br />

Eileen Bowser<br />

Paolo Cherchi Usai<br />

Christian Dimitriu<br />

Eric Le Roy<br />

Hisashi Okajima<br />

Susan Oxtoby<br />

Hillel Tryster<br />

Corespondents/Correspondants<br />

Thomas Christensen<br />

Ray Edmondson<br />

Silvan Furlan<br />

Steven Higgins<br />

Clyde Jeavons<br />

Paul Read<br />

Publisher / Editeur<br />

Christian Dimitriu<br />

Editorial Assistant<br />

Olivier Jacqmain<br />

Graphisme / Design<br />

Meredith Spangenberg<br />

Imprimeur / Printer<br />

Artoos - Brussels<br />

Fédération Internationale des<br />

Archives du <strong>Film</strong> - <strong>FIAF</strong><br />

Rue Defacqz 1<br />

1000 Bruxelles / Brussels<br />

Belgique / Belgium<br />

Tel: (32-2) 538 30 65<br />

Fax: (32-2) 534 47 74<br />

E-mail: jfp@fiafnet.org

Second Century Forum - Stockholm<br />

June 2003<br />

David Francis<br />

Open Forum<br />

From left to right: Jan de Vaal, Ernest<br />

Lindgren, Hans Wilhelm Lavries, Einar<br />

Lauritzen, Ove Busendorff, Mary Meerson at<br />

the <strong>FIAF</strong> Congress in Vence, 1953<br />

Editor’s note: The following essay is an annotated version <strong>of</strong> the paper<br />

that the author delivered in the Second Century Forum, June 4 2003,<br />

during the 59th <strong>FIAF</strong> Congress.<br />

At the last <strong>FIAF</strong> Congress, in Seoul, I looked at the “Challenges <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong><br />

Archiving in the 21st Century”. I would now like to turn my attention to<br />

the future role <strong>of</strong> <strong>FIAF</strong>. I want to do this by looking at the changes that<br />

have occurred within <strong>FIAF</strong> and those that have occurred outside the<br />

Federation.<br />

<strong>FIAF</strong> has a successful history. Not only has it provided its members with<br />

an intellectual forum for the exchange <strong>of</strong> knowledge, it has also put<br />

the importance <strong>of</strong> film preservation on international agendas. The work<br />

<strong>of</strong> its commissions, and the manuals that resulted, helped to define<br />

film archives as pr<strong>of</strong>essional bodies on a par with national museums<br />

and art galleries.<br />

The Federation had a clear identity when it started. It was a small<br />

group <strong>of</strong> passionate collectors and film enthusiasts who wanted to<br />

safeguard the art <strong>of</strong> the cinema and make classic films available in<br />

their respective countries. In<br />

those days, collection and<br />

screenings were the major<br />

activities because there<br />

were virtually no resources<br />

for preservation.<br />

Today <strong>FIAF</strong>’s identity is more<br />

diffuse. It has spent a lot <strong>of</strong><br />

time defining the rights and<br />

responsibilities <strong>of</strong><br />

membership but it has not<br />

come out with a precise<br />

mission statement<br />

supported by all members.<br />

Curators never seem to<br />

have been able to explain<br />

the Federation’s raison<br />

d’etre to their staff, and for<br />

financial reasons they are seldom able to invite their staff to<br />

Congresses, so they can see <strong>FIAF</strong> in action. I don’t think the Federation<br />

would have got such a reputation for elitism, if archive staff had<br />

understood its virtues, been committed to its activities and prepared to<br />

add their voices in its promotion.<br />

This is very sad because <strong>FIAF</strong> has achieved a lot. In fact, its identity crisis<br />

may stem from the fact that it succeeded in so many areas. For<br />

2 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 67 / 2004

Invité à intervenir dans le cadre du<br />

Second Century Forum de Stockholm,<br />

le 4 juin 2003, David Francis, fort de sa<br />

longue expérience - directeur du<br />

National <strong>Film</strong> and Television Archive<br />

(Londres), puis directeur du Motion<br />

Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded<br />

Sound Division/Library <strong>of</strong> Congress<br />

(Washington) – propose d’abord un<br />

rappel historique et critique de ce que<br />

fût originellement la <strong>FIAF</strong>.<br />

Née de l’enthousiasme d’un petit<br />

groupe de collectionneurs, convaincus<br />

de l’urgence de sauver l’héritage<br />

cinématographique mondial, la <strong>FIAF</strong><br />

est désormais une assemblée très<br />

large qui a du mal à définir sa raison<br />

d’être auprès de ses propres<br />

adhérents. Pourtant son action est<br />

unanimement reconnue, notamment<br />

dans les domaines de la conservation<br />

et du catalogage où ses commissions<br />

spécialisées ont défini les règles<br />

désormais en usage.<br />

Le fait que seul les directeurs des<br />

archives du film participent aux<br />

congrès (pour des raisons<br />

d’éloignement, aussi bien que de<br />

limites financières) explique sans<br />

doute en partie cette méconnaissance<br />

de l’importance de l’action de la <strong>FIAF</strong><br />

et de sa qualité de forum d’échanges.<br />

Plus récemment, la création en<br />

plusieurs lieux du monde<br />

d’associations régionales regroupant<br />

les cinémathèques d’un même espace<br />

géographique, témoigne aussi de<br />

cette incapacité désormais évidente<br />

pour la <strong>FIAF</strong> de répondre<br />

concrètement aux besoins multiples,<br />

et souvent fort différents,<br />

d’institutions ayant un but commun,<br />

mais des pr<strong>of</strong>ils divers.<br />

CLAIM en Amérique du Sud, l’ACE en<br />

Europe (et ses prolongements que<br />

sont Archimedia et Gamma), AMIA et<br />

CNAFA en Amérique du Nord et<br />

SEPAVAA en Asie et en Océanie, ont<br />

littéralement transformé le décor et<br />

interpellent la <strong>FIAF</strong> par leur vitalité et<br />

leurs initiatives.<br />

Par ailleurs les projets conjoints<br />

(congrès, symposia, publications) avec<br />

la Fédération internationale des<br />

Archives de télévision (FIAT), comme<br />

avec d’autres associations<br />

internationales, témoignent de la<br />

nécessité pour la <strong>FIAF</strong> d’élargir ses<br />

préoccupations et de se trouver de<br />

nouveaux alliés.<br />

instance, it established preservation and cataloguing standards and<br />

convinced producers that archives were a safe repository for their films.<br />

It is difficult for an organization that was first in its field to maintain<br />

momentum and it is even more difficult to reinvigorate it once the<br />

momentum is lost.<br />

However, because the Federation has tended to look inward rather than<br />

outward it has not always noticed what is happening in the film<br />

archive community that it spawned. The excitement <strong>of</strong> achievement is<br />

still very much present there. Although it is hard for a father or mother<br />

to take advice from the children, <strong>FIAF</strong> should look carefully at the<br />

regional associations the siblings have created to see why they are<br />

successful and should ask whether there is anything, it can do to help<br />

them.<br />

Let us examine the regional film preservation organizations. The first, in<br />

Latin America, appeared long before CLAIM was founded. I can’t even<br />

remember its name now. Not only was language a problem there - the<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficial <strong>FIAF</strong> languages were French and English and occasionally<br />

Russian -whereas they spoke mainly Spanish, but also the archives<br />

themselves were different from those in Europe. A large number were<br />

private organizations based on cine clubs. They didn’t receive state<br />

funding and were <strong>of</strong>ten at loggerheads with their authoritarian<br />

governments. They survived through collaboration with similar<br />

neighboring institutions. They couldn’t even take much advantage <strong>of</strong><br />

the treasured <strong>FIAF</strong> right to borrow prints because transport costs were<br />

too great. Unfortunately, over time, these archives have declined in<br />

importance or at best stood still. When the Uruguayan Archive<br />

submitted, on their behalf, a proposal that outlined their predicament<br />

in 1986, it was largely ignored by the Federation.<br />

The Union des Cinémathèques de la Communauté Européenne (UCE),<br />

the first incarnation <strong>of</strong> the organization now representing European<br />

archives, was established in the mid-eighties but it only came into its<br />

own when the European Union’s “Media” initiative made funds<br />

available for film preservation providing projects involved two or more<br />

countries. Previously the European archives had informal relationships<br />

with their colleagues. The prospect <strong>of</strong> funds encouraged them to get<br />

together as a group and talk about common problems.<br />

The Lumiere Project, the name given to this preservation program,<br />

lasted between 1991 and 1996 and was a great success. Since then, the<br />

European archives have never looked back. The formation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Association des Cinémathèques Européennes (ACE) enabled all<br />

European archives, not just those that were members <strong>of</strong> the European<br />

Union, to become members.<br />

It has spawned initiatives like Archimedia, a two pronged training<br />

program that provides three-year courses for students and two-week<br />

workshops for pr<strong>of</strong>essionals and the GAMMA group, an alliance <strong>of</strong> film<br />

laboratory and archive technical staff that undertakes in-depth<br />

research into preservation issues. The work <strong>of</strong> the group formed the<br />

basis <strong>of</strong> the publication ‘ The Restoration <strong>of</strong> Motion Picture <strong>Film</strong> ‘edited<br />

by Paul Read and Mark-Paul Meyer.<br />

The Nordic <strong>Film</strong> Archives also have their own regional organization that<br />

3 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 67 / 2004

Pour David Francis, il ne fait pas de<br />

doute que la <strong>FIAF</strong> devrait devenir une<br />

sorte d’Open Forum permettant des<br />

échanges, notamment sur les<br />

changements pr<strong>of</strong>onds qui affectent<br />

l’environnement pr<strong>of</strong>essionnel des<br />

archivistes du film. Pour ce faire, on ne<br />

devrait pas hésiter à élargir le<br />

membership de la Fédération : le<br />

risque en vaut amplement la peine.<br />

Au moment où la formation des<br />

futurs archivistes du film (un champ<br />

d’action exclusif à la <strong>FIAF</strong>, avec la<br />

création, en 1973, du Summer School<br />

biennal) est prise en charge par des<br />

institutions archivistiques, voire<br />

même universitaires, en Grande-<br />

Bretagne, aux Etats-Unis, en Italie et<br />

en Australie, la <strong>FIAF</strong> doit aussi<br />

redéfinir son intervention dans le<br />

domaine de l’éducation<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionnelle, un domaine<br />

déterminant pour l’avenir de nos<br />

institutions.<br />

L’UNESCO, à laquelle la <strong>FIAF</strong> a été très<br />

régulièrement associée, notamment<br />

dans l’élaboration de la Résolution sur<br />

la sauvegarde du patrimoine<br />

cinématographique dont le 25e<br />

anniversaire sera célébré bientôt, a<br />

récemment décidé d’inclure les<br />

œuvres de cinéma dans son<br />

programme Mémoire du monde : voici<br />

un autre lieu où la <strong>FIAF</strong> devrait<br />

intervenir activement.<br />

Le financement des archives du film<br />

change aussi : on nous demande de<br />

devenir des chercheurs d’or! En<br />

Europe, comme en Amérique, avec des<br />

approches différentes, nous sommes<br />

confrontés à ces nouvelles<br />

responsabilités.<br />

Pour toutes ces raisons, la <strong>FIAF</strong> doit<br />

changer : devenir un lieu d’évaluation<br />

et de mise en route des initiatives des<br />

associations régionales et, en même<br />

temps, un réseau permanent<br />

d’informations ; créer des occasions<br />

régulières de discussion sur les<br />

questions concrètes qui<br />

surdéterminent le travail des archives;<br />

redéfinir le rôle essentiel des<br />

commissions (qui travailleraient<br />

davantage sur des projets); être un<br />

lieu permanent de débats, ouvert et<br />

dynamique.<br />

invites technical experts to address specific regional problems and film<br />

practitioners and historians to talk about the cinema <strong>of</strong> the region.<br />

Elsewhere in the world, there are other kinds <strong>of</strong> regional groupings. The<br />

Southeast Asia Audio Visual Archives Association (SEAPAVAA), born out<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Asian organization, ASEAN, has gone beyond even continental<br />

boundaries and brought together archives with similar interests and<br />

problems from Asia and the Pacific Rim. Under the energetic leadership<br />

<strong>of</strong> Ray Edmondson, it now holds regular Congresses attended by some<br />

forty archives.<br />

In many ways, it is a miniature version <strong>of</strong> <strong>FIAF</strong> itself and it has made a<br />

decision that <strong>FIAF</strong> has yet to face by calling itself the Southeast Asia<br />

Audio Visual Archives Association. SEAPAVAA members always had<br />

difficulty attending <strong>FIAF</strong> Congresses because, in the past, they were<br />

mainly held in Europe or North America and the travel costs were<br />

beyond their means. They were also <strong>of</strong>ten frustrated because they did<br />

not feel the Federation was addressing the issues that particularly<br />

affected their region. Now they have their own organization it is going<br />

to be difficult to get them to participate actively in <strong>FIAF</strong> unless<br />

Congresses are held jointly. The Federation has finally recognized this<br />

problem and is planning to have more Congresses in this region in<br />

future but they will only work if European and North American archives<br />

don’t stay away.<br />

The Association <strong>of</strong> Moving Image Archivists (AMIA) was formed in the<br />

United States in 1990 and was successor to the <strong>Film</strong> Archives Advisory<br />

Committee (FAAC) and the Television Archives Advisory Committee<br />

(TAAC). It was intended as a purely national body but the mix <strong>of</strong><br />

institutional and individual members from audiovisual archives, the<br />

film industry and the academic community proved attractive to some<br />

<strong>FIAF</strong> members who wanted to see the Federation broaden its<br />

representation.<br />

AMIA now has at least thirty foreign members and is the largest<br />

association <strong>of</strong> audiovisual archive pr<strong>of</strong>essionals in the world. The<br />

annual Congresses are expensive but they provide an invigorating mix<br />

<strong>of</strong> meetings and activities that provide something for everybody and<br />

frustration for some.<br />

The Council <strong>of</strong> North American <strong>Film</strong> Archives (CNAFA) was established<br />

in 1998 because the larger film archives in the States, Canada and<br />

Central America were finding little opportunity to discuss issues <strong>of</strong><br />

interest to them in the multi-facetted AMIA environment. Strangely,<br />

CNAFA has a similar membership to FAAC, the organization that<br />

spawned AMIA., so we have now gone full circle. At present CNAFA is a<br />

very informal group with minimum organizational structure and a free<br />

form agenda. This has resulted in the sort <strong>of</strong> discussions I would like to<br />

see take place in <strong>FIAF</strong>.<br />

Then <strong>of</strong> course there are related organizations like the International<br />

Association <strong>of</strong> Sound Archives (IASA) and the International Association<br />

<strong>of</strong> Television Archives (FIAT/IFTA). A few years ago, IASA made a big play<br />

for the smaller film and audiovisual archives that failed to meet <strong>FIAF</strong>’s<br />

strict membership criteria, by including audiovisual in their title. IASA,<br />

like AMIA, welcomes individual and institutional members. Although<br />

4 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 67 / 2004

appropriate in the sound archive community, this policy presents<br />

problems for an international organization.<br />

FIAT/IFTA is a little different because its members mainly represent<br />

commercial or state-funded broadcasting organizations. Although<br />

concerned with the preservation <strong>of</strong> television programs, discussions are<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten centered on access to collections and better ways <strong>of</strong> making<br />

materials available to program makers. FIAT/IFTA has more financial<br />

resources than <strong>FIAF</strong> or IASA and does an excellent job training<br />

broadcasting archive staff. It used to alternate Congresses and training<br />

workshops, an idea that I thought <strong>FIAF</strong> should adopt, but in recent<br />

years has held both in the same year, but in different locations. Both<br />

IASA and FIAT/IFTA have joined <strong>FIAF</strong> in Joint Technical Symposiums, the<br />

first <strong>of</strong> which was held here in Stockholm in 1983. Usually these have<br />

been a great success. In 2000, IASA had a joint Congress with<br />

SEAPAVAA, the first time an international archival organization has held<br />

a joint meeting with a regional archival organization. This may become<br />

a pattern for the future.<br />

Although archivists don’t consciously choose to support the activities<br />

<strong>of</strong> regional associations rather than those <strong>of</strong> <strong>FIAF</strong>, geographical<br />

proximity, language and common concerns lead them in this direction.<br />

It is not surprising therefore that the rise <strong>of</strong> these groups in the<br />

nineties parallels the discussions about membership and the future <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>FIAF</strong> in the Federation.<br />

There are other significant changes. <strong>Film</strong> archivists now spend much <strong>of</strong><br />

their time raising funds or defending government subventions. They<br />

have also become more concerned with health and safety issues,<br />

employees’ rights, staff training and technical research. There is now<br />

much more oversight and, for instance, travel expenditure is directly<br />

related to the funds spent on preservation and access. Archivists have<br />

to demonstrate concretely the value <strong>of</strong> conference attendance. They<br />

can attend several national or regional events for the same cost as an<br />

international one. Also, like a good restaurant, a film archive works best<br />

when the curator stays close to home. Major problems surface quickly<br />

and they need to be on hand to defend the archives’ territory or ward<br />

<strong>of</strong>f predators. This <strong>of</strong>ten means they no longer have the time or the<br />

money to undertake a significant role in the Federation.<br />

<strong>FIAF</strong> is also no longer the sole source <strong>of</strong> technical information. The<br />

studios now appreciate the commercial appeal <strong>of</strong> selected restorations.<br />

The laboratories, which compete to serve both industry and archives,<br />

have therefore acquired equipment that is more sophisticated and<br />

found ways <strong>of</strong> increasing preservation quality. In the States they<br />

provide financial, and in-kind, support to AMIA. Laboratories would<br />

never consider giving concrete support to <strong>FIAF</strong> because the Federation<br />

doesn’t welcome them as members. In my opinion, any organization<br />

that is concerned with film preservation, supports the <strong>FIAF</strong> ‘Code <strong>of</strong><br />

Ethics” and maintains the technical standards to which the Federation<br />

aspires but, incidentally, has never documented, should be welcome as<br />

members.<br />

Commercial organizations can only use their membership for financial<br />

gain if other members let them. A real Open Forum where members<br />

5 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 67 / 2004

Invitado a participar en el Forum del<br />

Segundo Siglo (Second Century<br />

Forum), el 4 de junio de 2003, David<br />

Francis, con su larga experiencia–<br />

Director del National <strong>Film</strong> and<br />

Television Archive (London) y luego de<br />

Director del MBRS Division de la<br />

Library <strong>of</strong> congreso, propone una<br />

reseña histórica y crítica de lo que<br />

originariamente fue la <strong>FIAF</strong>.<br />

Nacida del entusiasmo de un<br />

pequeño grupo de coleccionistas<br />

convencidos de la urgencia de<br />

salvaguardar el legado<br />

cinematográfico mundial, la <strong>FIAF</strong> se<br />

ha ido transformando en una vasta<br />

asamblea que hoy tiene dificultades<br />

en justificar su razón de ser a sus<br />

adherentes. Y sin embargo su acción<br />

es reconocida unánimemente, en<br />

particular en su rol de modelo en la<br />

conservación y catalogación de<br />

películas, cuyas normas han sido<br />

desarrolladas e implementadas por<br />

las comisiones especializadas. El<br />

hecho de que sólo los directivos de los<br />

archivos cinematográficos asisten a<br />

los congresos explica en parte el<br />

desconocimiento del accionar de la<br />

<strong>FIAF</strong> y de su carácter de foro de<br />

intercambio de ideas y experiencias.<br />

La creación, relativamente reciente, de<br />

asociaciones regionales de<br />

cinematecas, es la expresión de la<br />

dificultad que tiene la <strong>FIAF</strong> en<br />

responder concretamente a las<br />

necesidades múltiples, y a menudo<br />

diferentes, de instituciones que tienen<br />

un objetivo común pero caracteres<br />

diversos, como la CLAIM en América<br />

Latina, la ACE en Europa (con sus<br />

prolongaciones en Archimedia y<br />

Gamma), AMIA y CNAFA en<br />

Norteamérica y SEAPAVAA en Asia y<br />

Oceanía. Estas asociaciones han<br />

modificado el panorama y, gracias a<br />

su vitalidad e iniciativas, constituyen<br />

un reto para la <strong>FIAF</strong>.<br />

Por otra parte, los proyectos conjuntos<br />

(congresos, simposios, publicaciones)<br />

emprendidos con la Federación<br />

Internacional de Archivos de<br />

Televisión (FIAT) y otras asociaciones<br />

internacionales, deberían incitar a la<br />

<strong>FIAF</strong> a ampliar sus preocupaciones y a<br />

salir en búsqueda de nuevos aliados.<br />

Para el autor, no cabe duda de que la<br />

<strong>FIAF</strong> debería funcionar como un Open<br />

Forum que permita el intercambio,<br />

particularmente fecundo en materia<br />

are prepared to challenge their colleagues’ actions as well as discuss<br />

mutual problems and the changing archival environment, will ensure<br />

that transgressors do not have a long life in the Federation. In short, the<br />

benefits <strong>of</strong> a broad-based membership far outweigh its dangers. I<br />

would not however go so far as to open the membership to individuals.<br />

Other changes in the film preservation world that exist outside <strong>FIAF</strong><br />

have an indirect impact on the Federation that it is more difficult to<br />

quantify. <strong>FIAF</strong> started its summer schools in 1973 and has held them<br />

more or less every four years since. However, they seldom last for more<br />

than two weeks and are aimed at existing archive staff with very little<br />

previous experience. Now other organizations are providing year- round<br />

film archive training that <strong>of</strong>ten leads to an accepted academic<br />

qualification, like an M.A. The first course was started at the University<br />

<strong>of</strong> East Anglia in 1989. The most successful in the United States is that<br />

held at the L Jeffrey Selznick School <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> at George<br />

Eastman House. In Italy, the film archive in Bologna has concentrated<br />

on the teaching <strong>of</strong> laboratory preservation practice. There is a distance<br />

learning film preservation course in Australia and UCLA has just started<br />

its own two-year MA course for film archivists in California that<br />

combines a strong library sciences component with film preservation.<br />

New York University is on the point <strong>of</strong> starting its own two-year MA<br />

course. On a less ambitious level the Collegiums at Pordenone take<br />

advantage <strong>of</strong> the experience present at the Festival to give selected<br />

students a chance to hear lectures on film history, preservation and<br />

other associated issues. Perhaps <strong>FIAF</strong> could establish a closer<br />

association with some <strong>of</strong> these training initiatives.<br />

There are also festivals <strong>of</strong> film preservation, at both UCLA and the<br />

Cinémathèque Française. Annual events in Bologna and Pordenone<br />

function in a similar way. The 1988 National <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> Act in the<br />

United States made the Librarian <strong>of</strong> Congress responsible for the<br />

selection <strong>of</strong> 25 American films representing every aspect <strong>of</strong> the<br />

country’s cinema heritage for inclusion in a National <strong>Film</strong> Registry.<br />

Selected titles from the Registry have been included in a tour that is<br />

designed to promote the importance <strong>of</strong> film preservation in every state.<br />

Now UNESCO is including films in its Memory <strong>of</strong> the World Register. I<br />

would like to see <strong>FIAF</strong>’s name associated with a similar event, maybe an<br />

annual festival <strong>of</strong> nitrate or restored films. This would be another<br />

opportunity to get archive staff from all over the world together each<br />

year. Even Cinefest, one <strong>of</strong> the four annual festivals in the States that<br />

show films held by private collectors, is starting to attract film<br />

archivists from other parts <strong>of</strong> the world. Kevin Brownlow’s television<br />

programs and film restorations for Thames Television in the UK have<br />

highlighted the importance <strong>of</strong> film preservation on the small screen<br />

and his restoration <strong>of</strong> Napoleon has been seen all over the world.<br />

Perhaps <strong>FIAF</strong> could commission Kevin to make a serious film about the<br />

activities <strong>of</strong> its members like the UK National <strong>Film</strong> Archive’s “Twentieth<br />

Century Treasure Trove”:<br />

Funding for film preservation is also changing. Most film archives used<br />

to rely on government support. Nowadays they find they can’t just sit<br />

back and wait for a check. Archives in the States have had to raze most<br />

<strong>of</strong> the preservation funds they need for some time and have come to<br />

6 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 67 / 2004

de reevaluación de los cambios<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>undos que afectan el entorno<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>esional de los archivistas<br />

cinematográficos. Desde este punto<br />

de vista, convendría ampliar la<br />

membresía de la Federación a nuevo<br />

insticuciones.<br />

En momentos en que en Gran<br />

Bretaña, Estados Unidos, Italia, y<br />

Australia la función de capacitación<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>esional de archivistas<br />

cinematográficos (que en su tiempo<br />

aseguraba con exclusividad la <strong>FIAF</strong>, a<br />

través de la Summer School creada en<br />

1973) está pasando a las instituciones<br />

de archivos y de las universidades. La<br />

<strong>FIAF</strong> debe, por ende, reconsiderar su<br />

política en materia de capacitación<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>esional, ya que ésta representa la<br />

clave para el futuro de nuestras<br />

instituciones.<br />

La UNESCO, con la que la <strong>FIAF</strong> ha<br />

estado vinculada permanentemente,<br />

en particular para la elaboración en<br />

1980 de las Recomendaciones para la<br />

salvaguarda del patrimonio, ha<br />

resuelto incluir las obras<br />

cinematográficas en su programa<br />

Memoria del Mundo. Este es otro<br />

terreno en el que la <strong>FIAF</strong> debería<br />

intervenir activamente.<br />

La financiación de los archivos<br />

cinematográficos también sufre<br />

cambios: ¡Nos exigen que nos<br />

hagamos buscadores de oro! Tanto en<br />

Europa como en América, de distintas<br />

maneras, estamos confrontados con<br />

estas nuevas responsabilidades.<br />

Por todas estas razones, la <strong>FIAF</strong> debe<br />

cambiar y transformarse en un centro<br />

de evaluación, dando impulso a las<br />

iniciativas de las asociaciones<br />

regionales y, al mismo tiempo,<br />

desarrollando una red permanente de<br />

información. Periódicamente, nuestra<br />

federación debe renovar las ocasiones<br />

de discusión sobre asuntos concretos<br />

que determinan el trabajo de los<br />

archivos y debe funcionar como<br />

centro abierto y permanente de<br />

debates.<br />

rely on not-for-pr<strong>of</strong>it organizations like the <strong>Film</strong> Foundation and the<br />

National <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> Foundation to coordinate fund raising and<br />

distribute the income to the archives.<br />

The split that has developed in recent years between the archives in<br />

the United States and those in Europe is partly the result <strong>of</strong> different<br />

funding models in the two regions. Public/private partnerships are the<br />

name <strong>of</strong> the game in the States and industry/archive arrangements<br />

that openly benefit both parties are also common. This close<br />

relationship between the producer and the archivist seems an<br />

anathema in Europe where most funds still come from governments.<br />

Private fund raising is becoming more common there, but it seldom<br />

involves such close relationships with the film industry as it does in the<br />

States.<br />

Perhaps this conflict could be avoided if the Federation defined more<br />

realistically the rule that requires film archives to be non-commercial.<br />

In the strictest sense, this is impossible in today’s world. Now that the<br />

archive movement is well established, one can probably take a more<br />

liberal approach to the issue. A more realistic definition would<br />

recognize that an archive has to charge for some services that were<br />

previously freely available and that <strong>of</strong>ten those charges are calculated<br />

on a cost-plus basis because this is the only way the archive can<br />

support non-income generating activities. There is nothing wrong with<br />

working with commercial entities as long as the relationship does not<br />

distort preservation priorities. Also, individual staff must not benefit<br />

from such arrangements and funds generated must only used for<br />

accepted archival activities.<br />

Therefore, what changes does <strong>FIAF</strong> need to make? Perhaps I could start<br />

with a proposal made by Wolfgang Klaue in 1994. He suggested<br />

programs <strong>of</strong> work, rather than standing commissions, that<br />

concentrated on solving specific problems and had set timetables.<br />

There is still work for the existing commissions to do but some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

tasks they undertook in the past, when <strong>FIAF</strong> was the only place one<br />

could acquire film preservation expertise, are being pursued by regional<br />

preservation groups. In addition, the very existence <strong>of</strong> standing<br />

commissions inhibits the formation <strong>of</strong> new groups, even ones with<br />

specific agendas and timetables.<br />

Here are some <strong>of</strong> the projects I would like to see incorporated into the<br />

new work program. The Federation could coordinate the activities <strong>of</strong><br />

the regional associations and act as a clearing-house for information so<br />

that duplication <strong>of</strong> effort is avoided. It could represent the regional<br />

associations in meetings with UNESCO and other related organizations<br />

like IASA, FIAT/IFTA, DOMITOR and IAMHIST. With care a powerful lobby<br />

can be built up that will benefit all the participants. It could, for<br />

instance, prepare for the 25th anniversary <strong>of</strong> the UNESCO resolution on<br />

the “Safeguarding and <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Moving Image” by<br />

examining the impact it has had and how it could be given more teeth<br />

in future.<br />

Now that film itself is threatened with extinction, there needs to be a<br />

group to consider the importance <strong>of</strong> film as an artifact. As I said in<br />

Seoul last year, archives will have to decide whether they stop<br />

7 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 67 / 2004

Poster with<br />

Mutoscope<br />

collecting films when they are no longer made or distributed on<br />

celluloid, continue to acquire so-called films even if they only exist in<br />

digital form or broaden their terms <strong>of</strong> reference to embrace all moving<br />

images including those generated on the internet. <strong>FIAF</strong> needs to take a<br />

position on this issue because members will need help in making this<br />

important decision.<br />

This group could also consider other issues associated with<br />

safeguarding the world film heritage. For instance, how can we ensure<br />

that the films preserved and available for research are representative <strong>of</strong><br />

the films created in a world where preservation funds are unequally<br />

distributed? It could also consider whether archives are successfully<br />

convincing a younger generation, brought-up on a diet <strong>of</strong> low quality<br />

moving images, <strong>of</strong> the importance <strong>of</strong><br />

spending significant funds on film<br />

preservation.<br />

Another group could start to prepare<br />

universal standards for archive<br />

activities like projection, print<br />

handling, and the shipment <strong>of</strong> film,<br />

to name just a few. These issues<br />

become important when there is a<br />

real possibility that today’s reference<br />

prints will become irreplaceable<br />

artifacts.<br />

Of course it will de difficult to find<br />

volunteers to work in these groups<br />

unless the Federation encourages a<br />

broader-based membership. On the<br />

other hand, there may be more<br />

enthusiasm for groups like these<br />

because their work is clearly<br />

beneficial to the film archive<br />

community as a whole but yet does<br />

not compete with that <strong>of</strong> the<br />

regional associations. Whatever<br />

happens it is vital that all<br />

geographical regions are represented<br />

in these work groups so that we do<br />

our best to eliminate the<br />

North/South, East/West divide.<br />

<strong>FIAF</strong> might also consider a list-serve<br />

that helps members solve immediate<br />

problems. Perhaps it could be hosted<br />

by a different large archive every one or two years. If there are still any<br />

archives that do not have access to the Internet and the web, the<br />

Federation could establish a special fund to help them buy the relevant<br />

equipment and if necessary pay any annual fees involved. Then all<br />

communications between the Brussels <strong>of</strong>fice and members could be<br />

electronic. Surely, this would lead to some savings even if it was only<br />

the cost <strong>of</strong> paper, envelopes and postage and it would certainly cut<br />

down on administrative time.<br />

8 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 67 / 2004

The Cinematograph in Prague, 1908<br />

The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> is the jewel in the Federation’s crown<br />

but there should be more frequent informal communication between<br />

members. An on-line newsletter that encourages thought-<strong>of</strong>-themoment<br />

contributions would be a great asset.<br />

These are just a few ideas to whet the appetite and encourage further<br />

thought and discussion. There are still many important roles for <strong>FIAF</strong><br />

but they must be developed in close cooperation with the regional film<br />

associations and they must involve the participation <strong>of</strong> members from<br />

every continent. The Federation should concentrate on issues that the<br />

regional associations and individual archives are unable to address; on<br />

problems that affect the world film heritage and concern every film<br />

archivist.<br />

9 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 67 / 2004

Projectionniste dans une cinémathèque<br />

(la Cinémathèque québécoise)<br />

François Auger<br />

Open Forum<br />

NDLR. Le travail du projectionniste est au cœur de la vie d’une<br />

cinémathèque et, au vu des bouleversements qui se pr<strong>of</strong>ilent à<br />

l’horizon (disparition du support film, valeur nouvelle des copies, etc.), il<br />

le sera encore plus dans les années qui viennent. Le présent dossier se<br />

présente donc essentiellement comme un document de travail. La<br />

première partie a été élaborée conjointement par la direction de la<br />

Cinémathèque québécoise et le syndicat de ses employés, au moment<br />

de la négociation d’une nouvelle convention collective de travail, au<br />

printemps de 2002. La seconde partie, a été originellement préparée en<br />

1982 par François Auger, directeur des Services techniques de la<br />

Cinémathèque, en collaboration avec Robert Daudelin, alors directeur<br />

général. Le texte a été régulièrement amendé pour répondre à des<br />

besoins nouveaux, voire à des modifications techniques de la cabine de<br />

projection; dans sa forme actuelle, il date de 1998.<br />

A. Le poste (tel que décrit en annexe de la convention collective de<br />

travail des employés de la Cinémathèque québécoise):<br />

Description du poste<br />

1. Le projectionniste prépare les films pour la projection, les<br />

inspecte, les répare et les nettoie au besoin, selon les standards<br />

archivistiques de la Cinémathèque;<br />

2. projette les films de tous formats et standards pratiqués par la<br />

Cinémathèque et procède à leur démontage après projection;<br />

3. consigne les informations techniques sur l’état des copies<br />

projetées et les achemine à qui de droit;<br />

4. assure l’entretien préventif, effectue les réparations d’urgence des<br />

équipements techniques et instruments de travail et les améliore<br />

à l’occasion;<br />

5. effectue les tests périodiques en vue d’assurer la qualité des<br />

projections;<br />

6. au besoin, recherche et identifie les extraits de films requis pour<br />

des projections spéciales, installe et teste l’équipement<br />

audiovisuel complémentaire;<br />

7. procède à l’installation, au calibrage et à la réparation des<br />

équipements techniques, à la demande du Directeur des Services<br />

techniques; définit et planifie les besoins en fournitures et veille à<br />

leur commande;<br />

8. entraîne les nouveaux projectionnistes;<br />

9. accomplit toute autre tâche connexe sous la direction ou à la<br />

demande du Directeur des Services techniques.<br />

10 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 67 / 2004

The projectionist’s skills are essential<br />

to the work <strong>of</strong> the film archive. As we<br />

anticipate the drastic changes <strong>of</strong><br />

moving image formats in the years to<br />

come, we must respond to the need<br />

to preserve and enlarge these skills.<br />

This article is a contribution to this<br />

goal and should be considered as a<br />

working document. Part one is the<br />

result <strong>of</strong> negotiation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

administration <strong>of</strong> the Cinémathèque<br />

Québécoise with its employees’ union<br />

in the course <strong>of</strong> drawing up a new<br />

contract in the spring <strong>of</strong> 2002. The<br />

second part was prepared in 1982 by<br />

François Auger, director <strong>of</strong> Technical<br />

Services, in collaboration with Robert<br />

Daudelin, then director general. The<br />

text has been amended as the need<br />

arose, and the present form is dated<br />

from 1998. Both parts describe the<br />

qualifications, the duties and<br />

responsibilities <strong>of</strong> the projectionist at<br />

the Cinémathèque Québécoise.<br />

Qualifications requises<br />

1. Diplôme de Secondaire V.<br />

2. Certificat de qualification, catégorie opérateurs de machines<br />

cinématographiques.<br />

3. Trois années d’expérience dans la projection cinématographique<br />

ou l’équivalent.<br />

4. Habileté technique et mécanique et sens de la méthode et de la<br />

précision.<br />

5. Bonne connaissance du français et connaissance d’usage de<br />

l’anglais.<br />

6. Aptitude à communiquer avec la clientèle.<br />

B. Les tâches (telles que décrites dans le Cahier des charges remis au<br />

projectionniste au moment de son embauche):<br />

Le projectionniste est beaucoup plus qu’un simple technicien : c’est la<br />

personne qui a la responsabilité de la cabine de projection et,<br />

conséquemment, de la qualité des projections de la Cinémathèque.<br />

Cette responsabilité est multiple; on peut la répartir selon les<br />

catégories suivantes :<br />

1. Tâches quotidiennes :<br />

• préparation (inspection, réparation, nettoyage) des films;<br />

• tests, si nécessaire (format d’image, vitesse de projection, son,<br />

etc.);<br />

• nettoyage des projecteurs (corridors de défilement, roues<br />

d’entraînement);<br />

• fermeture des rideaux;<br />

• rangement des lentilles;<br />

• démontage des films de la journée;<br />

• rédaction de la fiche technique pour chaque film projeté.<br />

2. Tâches hebdomadaires :<br />

• entretien de l’équipement (lentille image,lentille son, lampe<br />

excitatrice, huilage : tête magnétique du projecteur 16mm, roues<br />

de guidage du projecteur 16mm, bobines réceptrices des<br />

projecteurs 35mm);<br />

• nettoyages des vitres de la cabine;<br />

• corrections et commentaires du « cue sheet » qui doit être<br />

retourné au Directeur de la Programmation à la fin de chaque<br />

semaine.<br />

3. Tâches mensuelles :<br />

• tests de stabilité;<br />

11 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 67 / 2004

• tests de son;<br />

• répartition de la lumière;<br />

• nettoyage des miroirs des lanternes.<br />

4. Tâches périodiques :<br />

• changement d’huile du projecteur 16mm (1 fois par 6 mois);<br />

• rotation des lampes de projection (1 fois par 6 mois);<br />

• ménage et entretien général de la cabine (acquisition des pièces<br />

et fournitures nécessaires au bon fonctionnement de la cabine de<br />

projection, rangement, etc.);<br />

• réparations mineures;<br />

• vérification du système sonore public (P.A. system);<br />

• étiquetage des boîtes des films de la collection de la<br />

Cinémathèque.<br />

5. Préparation et entretien des films :<br />

• tout film de la collection de la Cinémathèque doit être retourné<br />

aux entrepôts de conservation correctement «rembobiné»<br />

(émulsion vers l’extérieur);<br />

• tout film doit être retourné aux entrepôts de conservation en<br />

parfait état : repères correctement faits, perforations réparées (si<br />

endommagées), amorces posées selon les normes, etc.;<br />

• tout film doit être retourné sur sa bobine d’origine;<br />

• une fois « rembobiné », le film est maintenu en place par un<br />

ruban adhésif (« masking tape »); par contre, aucun ruban adhésif<br />

ne doit retenir le film au noyau;<br />

• les copies de projection sur base acétate doivent être expédiées<br />

selon les directives de la <strong>FIAF</strong> (juin 1982), en annexe;<br />

• sauf exception, tout film destiné à une projection publique doit<br />

être vérifié 48 heures avant sa projection;<br />

• en aucun cas doit-on couper d’images – surtout pas pour laisser<br />

une image sur l’amorce à des fins de repérage;<br />

• si des perforations sont endommagées, il faut les réparer en<br />

évitant que le ruban collant ne touche l’image;<br />

• il faut nettoyer le film, après chaque réparation, ou chaque<br />

nouvelle collure;<br />

• si une collure s’est « étirée », il faut la refaire;<br />

• il faut éviter de couper l’image, même dans le cas où le film est<br />

déchiré;<br />

• il faut toujours s’assurer que le ruban collant utilisé pour une<br />

réparation ne dépasse pas les côtés du film;<br />

• en aucun cas peut-on utiliser le « masking tape » comme repère<br />

ou à d’autres fins : tout « masking tape » doit être enlevé du film<br />

ou de l’amorce avant une projection;<br />

12 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 67 / 2004

La capacitación de los operadores de<br />

proyección constituye un elemento<br />

esencial para la labor de las<br />

cinematecas. Ante el advenimiento de<br />

cambios pr<strong>of</strong>undos en los formatos y<br />

sistemas de producción y difusión de<br />

las imágenes en movimiento,<br />

debemos responder a la necesidad de<br />

preservar y ampliar los conocimientos<br />

y experiencia de los operadores.<br />

El presente artículo es una<br />

contribución al logro de ese objetivo y<br />

debe ser considerado como un<br />

documento de trabajo. La primera<br />

parte es el resultado de la negociación<br />

de la administración de la<br />

Cinémathèque Québécoise con el<br />

sindicato iniciada en vistas de la firma<br />

de una convención en 2002. La<br />

segunda parte fue redactada en 1982<br />

por François Augier, director de los<br />

Servicios Técnicos, en colaboración con<br />

Robert Daudelin, en aquel entonces<br />

director general. El texto ha sido<br />

modificado en función de las<br />

necesidades. En ambas partes se<br />

describen las calificaciones, deberes y<br />

responsabilidades del operador de<br />

proyecciones de la Cinémathèque<br />

Québécoise.<br />

• toute amorce douteuse (incomplète, abîmée, sale) doit être<br />

remplacée, y compris l’amorce de projection (ex : il manque des<br />

cadres dans l’amorce SMPTE, des perforations sont endommagées<br />

et non réparables, il y a des saletés ou des rayures excessives, etc.);<br />

• les repères magnétiques ne doivent jamais être visibles dans<br />

l’image;<br />

• les films doivent être préparés de façon à ce que l’un ou l’autre<br />

des projectionnistes de la Cinémathèque puisse le projeter sans<br />

problème.<br />

6. Format d’image, piste sonore et vitesse de projection:<br />

• Le projectionniste est responsable du format d’image. En cas de<br />

doute, il consulte les responsables du programme. Afin d’éviter<br />

toute erreur, le format dit muet (plein cadre) sera identifié selon<br />

sa réalité physique de 1.33; pour les mêmes raisons, le cadre<br />

sonore (« flat ») sera identifié 1.37.<br />

• Le projectionniste est responsable de l’identification du type de<br />

piste sonore : DTS, Dolby numérique, Dolby SR, Dolby A ou mono,<br />

etc. Ces informations doivent être reportées sur l’étiquette de la<br />

boîte contenant le film et transmises au secteur Catalogage.<br />

• Même dans le cas où il y a des problèmes sonores, les niveaux<br />

sonores ne doivent jamais être haussés au-delà de la limite<br />

normale.<br />

• Le son du système Dolby doit obligatoirement être sur « mute »<br />

au moment de l’amorçage du projecteur 16mm.<br />

• Si l’information ne lui a pas déjà été communiquée, le<br />

projectionniste détermine la vitesse de projection des films<br />

muets, au besoin en consultant le Directeur de la Programmation.<br />

• Les tests de projection doivent être faits au moins trente minute<br />

avant la séance publique.<br />

7. Boîtes métalliques :<br />

• Toute boîte métallique (dite « de labo ») endommagée doit être<br />

remplacée immédiatement. Les boîtes doivent toujours être<br />

propres, à l’intérieur comme à l’extérieur : dans la mesure du<br />

possible, toute étiquette et toute écriture au crayon de feutre<br />

doivent être enlevées. Seule l’étiquette Cinémathèque québécoise<br />

doit être apposée sur les boîtes de la collection.<br />

8. Propreté, sécurité, entretien, etc. :<br />

• la porte de la cabine doit être verrouillée en tout temps;<br />

• le système de son doit être en position « muette » entre les<br />

séances;<br />

• les rideaux de l’écran doivent être fermées entre les séances;<br />

• à la fin de chaque jour, les lentilles des projecteurs 35mm<br />

doivent être rangées dans l’armoire métallique qui leur est<br />

réservée;<br />

13 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 67 / 2004

Ce dossier devrait être lu en parallèle<br />

avec « The Advanced Projection<br />

Manual » de Torkell Saetervadet,<br />

ouvrage publié sous la direction de la<br />

Commission de programmation et<br />

d’accès de la <strong>FIAF</strong> et dont six chapitres<br />

sont déjà disponibles sur le site<br />

internet de la <strong>FIAF</strong>.<br />

• les micros doivent être rangés dans cette même armoire;<br />

• le projectionniste doit fournir sa collaboration aux techniciens<br />

de l’extérieur qui assurent l’entretien de l’équipement;<br />

• il est strictement interdit de boire et de manger dans la cabine<br />

de projection;<br />

• le projectionniste ne peut jamais s’absenter de la cabine quand<br />

une projection est en cours;<br />

• le projectionniste ne doit jamais s’adresser aux spectateurs de la<br />

salle : il communique ses commentaires directement au Directeur<br />

des Services techniques;<br />

• tout accident de projection (film brisé, pellicule brûlée, inversion<br />

de bobine, etc.) doit être immédiatement signalé au Directeur<br />

général.<br />

14 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 67 / 2004<br />

Cabine de projection de la Cinématheque québecoise en pleine action

Contribution à une histoire de la<br />

Cinémathèque française*<br />

Pierre Barbin<br />

Historical<br />

Column<br />

Chronique<br />

historique<br />

Columna<br />

histórica<br />

* Texte originellement paru dans la revue<br />

française « Commentaire » (n°101,<br />

printemps 2003) reproduit ici avec<br />

l’aimable autorisation de l’auteur et de<br />

son éditeur.<br />

Dans les années 30, au moment de l’avènement du cinéma parlant, les<br />

ciné-clubs, nombreux à Paris, ont souffert de la disparition progressive<br />

des films muets, source d’une grande nostalgie des cinéphiles. Les<br />

animateurs de ces associations s’orientèrent vers l’acquisition de copies<br />

afin de créer une filmothèque pour les présenter à leurs membres. Ce<br />

fut le projet de Jean-Placide Mauclaire et Jean Mitry en 1930 à la suite<br />

du grand succès du gala Georges Méliès à la salle Pleyel, qui confirma<br />

de manière éclatante l’intérêt de tout un public pour les films anciens.<br />

Pour des raisons financières, Jean-Placide Mauclaire devait bientôt<br />

abandonner ce projet et se cantonner dans une salle de répertoire à<br />

Montmartre. L’État tenta la création d’une cinémathèque nationale en<br />

1932. Georges Huisman, directeur général des Beaux-Arts, confia celle-ci<br />

à Laure Albin-Guillot, chargée des archives photographiques des Beaux-<br />

Arts et elle-même photographe réputée. Cette cinémathèque nationale<br />

fut inaugurée par Jean Mistler, sous-secrétaire d’État, le 10 janvier 1933<br />

au Trocadéro. Des galas devaient assurer son financement ; une soirée<br />

au cirque Médrano, le 31 mars 1933, placée sous le patronage du<br />

président de la République, Albert Lebrun, constituera la seule activité<br />

de cette cinémathèque mort-née, faute de crédits et surtout d’une<br />

réelle volonté. On peut noter par ailleurs qu’une commission<br />

interparlementaire sous la présidence de Jean-Michel Renaitour, député<br />

de l’Yonne, étudia en 1936 les divers aspects de l’industrie<br />

cinématographique. La création d’une cinémathèque chargée de<br />

présenter les films dans une sorte de « Comédie-Française du cinéma »<br />

fut proposée par Pierre Lafitte. Un rapporteur fut désigné et malgré<br />

l’intérêt du ministre Jean Zay, ce projet n’aboutit pas. À aucun moment<br />

la commission ne jugea utile de faire appel à Pierre-Auguste Harlé,<br />

Henri Langlois ou Jean Mitry sur un sujet que ceux-ci connaissaient<br />

pourtant bien. Des cinémathèques existaient déjà à Londres, Berlin,<br />

New York et Stockholm. L’ idée était dans l’air mais faute d’un plan<br />

d’action et de moyens financiers elle ne connut aucune suite jusqu’au<br />

dépôt, le 2 septembre 1936, des statuts d’une association (régie par la<br />

loi de 1901) dite « Cinémathèque française » par Harlé et Langlois.<br />

Création<br />

Les buts poursuivis étaient définis ainsi : – « grouper les différents<br />

possesseurs de films et toute personne désireuse de défendre et<br />

sauvegarder le répertoire cinématographique ; – rechercher et conserver<br />

tous documents ayant trait au cinéma et certains films positifs et<br />

négatifs ; – réunir une documentation permettant de connaître et de<br />

cataloguer les œuvres cinématographiques tournées dans le monde<br />

entier depuis l’origine du cinéma jusqu’à nos jours. » Le premier conseil<br />

d’administration groupait Pierre-Auguste Harlé, président et trésorier,<br />

Henri Langlois, secrétaire, Georges Franju, chargé des recherches, et<br />

Jean Mitry, archiviste. Le président, directeur de l’hebdomadaire<br />

15 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 67 / 2004

corporatif La Cinématographie française, apportait les premiers fonds et<br />

le soutien de son journal. La recherche et la conservation des films en<br />

voie de disparition visaient la sauvegarde des films de répertoire. Leur<br />

présentation hebdomadaire par le Cercle du cinéma justifiait cette<br />

démarche et ce n’est qu’après plusieurs années que la doctrine des<br />

grandes bibliothèques « Ne pas choisir mais tout conserver » fut<br />

revendiquée. Un organisme encore modeste débutait. La compétence<br />

de Jean Mitry, l’enthousiasme de Georges Franju et de Henri Langlois,<br />

aides par la bienveillance de Pierre-Auguste Harlé et par celle de la<br />

famille Langlois, permirent de susciter l’intérêt des pr<strong>of</strong>essionnels,<br />

cinéastes et producteurs. Le jeune Langlois sût les convaincre.<br />

Soulignons l’efficacité de cette initiative qui s’affirme face aux<br />

tentatives avortées.<br />

La Fédération internationale des archives du film<br />

Moins de deux ans après ce début, le 17 juin 1938, la Cinémathèque<br />

française appuyait la création de la Fédération internationale des<br />

archives du film (<strong>FIAF</strong>) qui regroupait autour d’elle trois cinémathèques<br />

qui l’avaient précédée :<br />

– la <strong>Film</strong> Library du MOMA de New York, qui existait depuis 1935,<br />

représentée par Iris Barry ;<br />

– la National <strong>Film</strong> Library de Londres, fondée également en 1935, sur<br />

recommandation de la Chambre des Communes au sein du British <strong>Film</strong><br />

Institute, représentée par Olwen Vaugham ;<br />

– la Reichsfilmarchiv, créée par le Dr Joseph Goebbels le 6 décembre<br />

1934 et inaugurée solennellement à Berlin par Adolf Hitler le 4 février<br />

1935, représentée par Frank Hensel envoyé par le ministère de la<br />

Propagande, membre du Parti national-socialiste depuis 1928 et de la<br />

SS depuis 1938.<br />

Les statuts stipulaient que cette fédération était ouverte à toute<br />

cinémathèque nationale se conformant aux règlements stricts des<br />

quatre fondateurs. Le premier congrès eut lieu à New York le 26 juillet<br />

1939, cinq semaines avant la déclaration de la guerre. Au cours de cette<br />

réunion, Frank Hensel fut élu président, Henri Langlois, secrétaire<br />

général, Olwen Vaugham, trésorière. Le choix d’un président<br />

appartenant au ministère de la Propagande national-socialiste pouvait<br />

paraître inquiétant. Georges Franju, interrogé à ce sujet par Richard<br />

Roud, minimisait : « Ce n’était pas un problème […] la gauche était<br />

pacifiste (1) . » Dans un document du Parti nazi, signé par lui, avant son<br />

départ à New York le 5 juillet 1939, Frank Hensel indique ses fonctions<br />

au Reichsfilmarchiv comme secondaires. En fait, la place hiérarchique de<br />

ce représentant du ministère de la Propagande est d’un tout autre<br />

niveau (2) . Fonctionnaire de l’État et des services secrets, il pouvait<br />

considérer Henri Langlois comme une source d’information sur le<br />

cinéma occidental et avant tout une possibilité de se procurer les films<br />

d’intérêt politique ou militaire qu’il recherchait. À ce titre, il tenta<br />

vainement, dès juillet 1940, de joindre Langlois à son domicile, mais<br />

celui-ci se trouvait encore en Touraine, où il avait été mobilisé en avril.<br />

Lorsqu’il regagna Paris, Hensel était en mission à Vichy où Yvonne<br />

Dornès (3) le rencontra début septembre. Cet entretien préparait les<br />

activités à venir.<br />

16 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 67 / 2004

The author, who was named director<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Cinémathèque Française<br />

during the 1968 crisis, provides his<br />

perspective on the stormy history <strong>of</strong><br />

the archive. Tracing the origins <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Cinémathèque, and the creation <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>FIAF</strong> before the war, he then<br />

contributes specific details <strong>of</strong> the<br />

activities <strong>of</strong> Henri Langlois during the<br />

Nazi occupation <strong>of</strong> France, and his<br />

ambiguous relationship with Frank<br />

Hensel, an important <strong>of</strong>ficial in the<br />

Nazi Ministry <strong>of</strong> Information and<br />

Propaganda, at the same time<br />

president <strong>of</strong> the Reichsfilmarchiv <strong>of</strong><br />

Berlin and the first elected president<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>FIAF</strong>. The Cinémathèque was given<br />

space in the same building with the<br />

Reichsfilmarchiv and worked in close<br />

relationship.<br />

A long time after the Liberation, the<br />

activities <strong>of</strong> the Cinémathèque in<br />

1942 and 1943 remained hidden.<br />

Barbin says that Les Cahiers du cinéma<br />

swallowed whole the version <strong>of</strong><br />

Langlois, ignoring thus, 25 years after<br />

the events, the support <strong>of</strong> the Laval<br />

government, the subventions <strong>of</strong> Vichy<br />

and the collaboration with the<br />

German authorities. After the<br />

Liberation, Henri Langlois asked the<br />

government for the continuation <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>FIAF</strong> subvention in which the<br />

Cinémathèque had maintained itself<br />

all during the occupation, but now<br />

claimed that <strong>FIAF</strong> suspended its<br />

activities in 1940 and was resuming<br />

them again. This was accepted by the<br />

authorities as fact, making <strong>of</strong>ficial the<br />

lie that exonerated the Cinémathèque<br />

<strong>of</strong> all embarrassing complicity.<br />

According to the author, no debate<br />

was held during the fifties on the<br />

objectives to attain or tasks to<br />

prioritize. There were some protests,<br />

quickly stifled, concerning the<br />

disappearance <strong>of</strong> films or documents:<br />

J.-P. Mauclaire, for example, who had<br />

entrusted his collection <strong>of</strong> Méliès<br />

which disappeared in 1945. He asked<br />

in vain during the general assembly <strong>of</strong><br />

July 1946 for the publication <strong>of</strong> the<br />

“catalogue <strong>of</strong> films that the<br />

Cinémathèque has a mission to<br />

conserver.” Jean Painlevé attempted<br />

during the general assembly <strong>of</strong> 1962<br />

to institute reforms. His proposals<br />

were pushed back thanks to the proxy<br />

votes concentrated in a single hand.<br />

He concluded: “The Cinémathèque<br />

has become such a personal<br />

Sous l’Occupation<br />

Toute activité en zone occupée dépendait de l’autorisation des<br />

autorités allemandes; une ordonnance de la Militärbefehlshaber in<br />

Frankreich du 28 août 1940 fixait les conditions de cette autorisation.<br />

Les associations devaient déposer un dossier bilingue comportant les<br />

statuts, la composition du conseil d’administration et les projets<br />

d’activités à l’appui de leur demande. Frank Hensel convoqua le 15<br />

septembre à l’hôtel Westminster rue de la Paix à Paris une réunion où<br />

Henri Langlois et Georges Franju rencontrèrent les représentants des<br />

autorités allemandes. Les deux cinéphiles français furent ce jour-là<br />

confirmés respectivement secrétaire général de la Cinémathèque et<br />

secrétaire exécutif de la Fédération internationale des archives du film,<br />

ce qui correspondait à la reconduction de leur situation d’avant-guerre<br />

mais dorénavant sous l’autorité du président Hensel. La Cinémathèque<br />

avait ainsi pignon sur rue avant même la création du Comité<br />

d’organisation de l’industrie cinématographique (COIC) par Vichy le 2<br />

décembre 1940. Georges Franju remettra en mars 1945 un compterendu<br />

confirmant cette autorisation d’exercer au ministère des Affaires<br />

étrangères (4) . Frank Hensel n’était pas à Paris seulement comme<br />

représentant du Reichsfilmarchiv et président de la <strong>FIAF</strong>. Il participait à<br />

des négociations engagées par le ministère de l’Information et de la<br />

Propagande de Berlin et joua ainsi, pendant l’hiver 1940-41, un rôle<br />

important dans la fusion des actualités françaises et allemandes aux<br />

côtés de Fritz Tietz, administrateur de Deutsche Wochenschau (5) . Cette<br />

fusion fut l’objet de la Convention Abetz-Brinon du 18 août 1941. L’<br />

attitude d’Hensel semble avoir été conforme aux instructions de Berlin<br />

qui préparait l’instauration d’une servitude volontaire ou, du moins,<br />

acceptée. La Reichsfilmarchiv dépendait directement du ministère de<br />

l’Information et de la Propagande du Dr Goebbels. Celui-ci se réjouissait<br />

en juillet 1940 à l’idée d’un voisin faible et dirigé, le préparant à « son<br />

avenir de grande Suisse (6) ». Il pensait qu’il ne fallait pas « montrer<br />

inutilement ses chaînes à un peuple asservi ». Dans une autre réunion,<br />

tenue à Berlin en juillet 1941, Goebbels décida que les films français<br />

constituaient à l’exportation un complément de la production<br />

allemande pour tout le continent européen. Aucune société<br />

d’exportation française ne serait autorisée. Il entendait anéantir la<br />

présence culturelle de la France à l’extérieur et créer des organismes<br />

européens sous contrôle allemand (7) . Une cinémathèque européenne<br />

avec son siège à Berlin correspondait à ce projet, ce qui explique le rôle<br />

dévolu à Frank Hensel. L’ intervention allemande se confirma en 1942<br />

concernant la Cinémathèque française. Une lettre adressée à Berlin<br />

informait les services du Dr Goebbels que Robert Buron, secrétaire<br />

général du Comité d’organisation de l’industrie cinématographique<br />

(COIC), envisageait de créer, au sein du COIC ou sous son contrôle, une<br />

cinémathèque pour assurer la responsabilité des archives<br />

cinématographiques et proposait des mesures détaillées (8) .Les<br />

autorités allemandes devaient rejeter ce projet et indiquer qu’il ne<br />

pourrait être accepté que dans le cadre de la <strong>FIAF</strong>, présidée par Frank<br />

Hensel. Il serait alors convenable de rattacher la Cinémathèque<br />

française au ministère de l’Information via la Direction du cinéma,<br />

toute autre cinémathèque devant être dissoute. C’est conformément à<br />

ces interventions qu’en octobre 1942 des accords entre la<br />

Cinémathèque française et la Reichsfilmarchiv furent instaurés. La<br />

17 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 67 / 2004

enterprise that one may not criticize<br />

certain directors without having the<br />

appearance <strong>of</strong> attacking the<br />

organization itself.”<br />

The author describes the situation<br />

after André Malraux’s arrival in 1959<br />

as Minister <strong>of</strong> Culture. It meant<br />

increased subventions for the<br />

Cinémathèque and the creation <strong>of</strong> a<br />

new projection theater in the Palais<br />

de Chaillot, a new <strong>of</strong>fice at rue de<br />

Courcelles, and a line in the State<br />

budget for the printing <strong>of</strong><br />

preservation copies. The Minister<br />

announced at Cannes that the<br />

Cinémathèque would become the<br />

best in the world, a promise that he<br />

confirmed to the National Assembly.<br />

The fire at rue de Courcelles on 10 July<br />

1959 some weeks after the<br />

inauguration <strong>of</strong> the new <strong>of</strong>fice<br />

apparently did not disturb the<br />

authorities. It was, however, the<br />

author says, at the origin <strong>of</strong> the<br />

exclusion <strong>of</strong> the Cinémathèque by<br />

<strong>FIAF</strong> because <strong>of</strong> the destruction <strong>of</strong><br />

more than a hundred films lent by<br />

other film archives and the absence <strong>of</strong><br />

any inventory which would have been<br />

able to show the importance and the<br />

nature <strong>of</strong> the damage. The increase in<br />

the government’s financial<br />

participation, in addition to the new<br />

responsibilities <strong>of</strong> the archive made<br />

mandatory by the law that forbid the<br />

distribution <strong>of</strong> nitrate copies, thus<br />

forcing their deposit in the<br />

Cinémathèque, gave the archive a<br />

public role that should have modified<br />

its nature. A series <strong>of</strong> articles in le<br />

Monde in August 1962 contributed to<br />

the myth <strong>of</strong> “the dragon who watches<br />

over our treasures.” Langlois’s version<br />

<strong>of</strong> the legal aspects <strong>of</strong> films in the<br />

collection was that the films could be<br />

withdrawn any time he chose, as<br />

though he were in charge <strong>of</strong> a private<br />

collection, not a public institution:<br />

this became a weapon to force the<br />

government to do as Langlois wanted.<br />

The problems between the<br />

Cinémathèque and the government<br />

began at the end <strong>of</strong> December 1964,<br />

when a director in Malraux’s cabinet<br />

asked that Finance audit the<br />

institutions receiving government<br />

funds: IDHEC, Unifrance <strong>Film</strong>, the<br />

Cannes <strong>Film</strong> Festival and the<br />

Cinémathèque Française. This audit,<br />

which found no problem at the other<br />

institutions, was interpreted at the<br />

direction générale de la cinématographie en fera état : « La<br />