Dances of India.pdf - Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan

Dances of India.pdf - Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan

Dances of India.pdf - Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

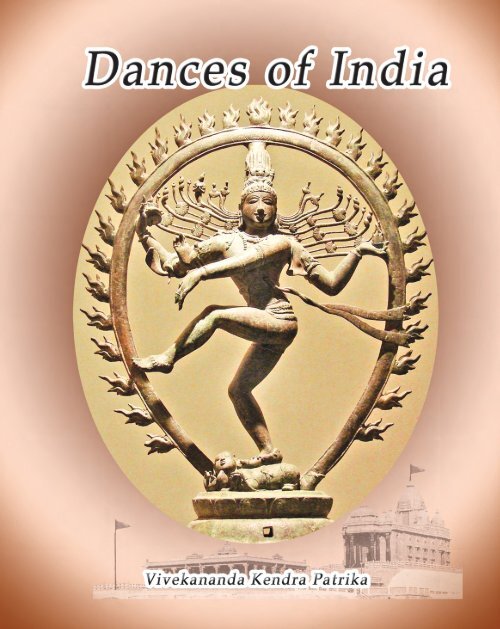

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKADANCES OF INDIADANCES OF INDIACONTENTS1. Acknowledgements 12. Editorial Dr.Padma Subrahmaniam 33. The Dance <strong>of</strong> Shiva Ananda K. Coomaraswamy 154. The Gift <strong>of</strong> Tradition K. S. Ramaswami Sastri 205. The Spiritual Background <strong>of</strong><strong>India</strong>n Dance Rukmini Devi 256. The Renaissance <strong>of</strong> <strong>India</strong>n Dance andits Consequences Mohan Khokar 307. The Art <strong>of</strong> Dance Dr. C. P. Ramaswami Iyer 358. The Place <strong>of</strong> Language in Dance Pr<strong>of</strong>. C. V. Chandrasekhar 409. Waiting in the Wing Usha Jha 4710. The Ramayana in <strong>India</strong>n Danceand Dance-Drama Mohan Khokar 5411. The Art and The Artist K. S. Ramaswami Sastri 6012. Kuchipudi Dance V. Patanjali 6213. The Veedhi <strong>of</strong> Bhagavatam Andhra Dr. V. Raghavan 6914. Bhagavata Mela - Dance-Drama S. Natarajan 7215. Koodiyattom D. Appukuttan Nair 7416. Origin and Development <strong>of</strong> Thullal P. K. Sivasankara Pillai 7717. Kathakali-The Total Theatre M. K. K. Nayar 8118. Mohiniaattam Dr. (Smt.) Kanak Rele 9719. Bharatanatyam Smt.Chitra Visweswaran 102

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKADANCES OF INDIA20. Dance can Play a Therapeutic Role Smt.Sudharani Raghupathy 10521. Yakshagana Bayalata K. S. Upadhyaya 10822. A Glimpse Into Odissi Dance Dr. Minati Mishra 11523. Mayurabhanj Chhau Dr. (Mrs.) Kapila Vatsyayan 12124. Kathak Dance as an Art -Form Dr. S. K. Saxena 13225. Udayshankar Moni Bagchee 13526. Temples as Patrons <strong>of</strong> Dance Dr. K. V. Raman 13827. Therukkoothu-The Folk-Theatre <strong>of</strong>Tamilnad Smt. Shyamala Balakrishnan 14028. Chakkiyar Koothu Mrinalini Sarabhai 14429. <strong>Vivekananda</strong> <strong>Kendra</strong> Samachar 14630. Folk-<strong>Dances</strong> <strong>of</strong> Gujarat Parul Shah 16931. Folk-<strong>Dances</strong> <strong>of</strong> Punjab - Bhangra Dr. (Mrs.) Kapilavatsyayan 17532. Folk-<strong>Dances</strong> <strong>of</strong> Haryana Sudhir K. Sharma 17833. Folk-<strong>Dances</strong> <strong>of</strong> Madhya Pradesh Dr. (Mrs.) Kapila Vatsyayan 18134. Natya Tradition in Maharashtra Sucheta Bhide 18435. Folk-<strong>Dances</strong> <strong>of</strong> Rajasthan Dr. (Mrs.) Kapila Vatsyayan 18836. Folk-<strong>Dances</strong> <strong>of</strong> West Bengal Dr. (Mrs.) Kapila Vatsyayan 19237. Manipuri Dance Darshana Jhaveri 19438. Folk-<strong>Dances</strong> <strong>of</strong> Arunachal Pradesh Niranjan Sarkar 19640. Assamese Dance Pradeep Chaliha 205

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKAWe are very thankful to artiste Kalpanawho managed to get a good. number <strong>of</strong>valuable photographs which have beenused in this volume. Our thanks are alsodue to ‘SITRA’ who did the cover design inspite <strong>of</strong> his heavy pre-occupation withother commitments. We are indeed verythankful to M/s. Rajsri Printers for theirneat handling <strong>of</strong> the work and the speed2DANCES OF INDIAwith which they executed the wholevolume. While every care has been takento see that no party is left out in ouracknowledgement for their meritoriousassistance and co-operation, we earnestlysolicit forgiveness for any mistake <strong>of</strong>omission or commission which, <strong>of</strong> course,has not been deliberate.

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA3DANCES OF INDIABHARATIYA NATYA AND NRITTAEDITORIALDr. PADMA SUBRAHMANIAMThe earliest extant literature on thesubject <strong>of</strong> <strong>India</strong>n Dance is Bharata’sNatyasastra. There seems to havebeen some Nata Sutras even before thisSastra was penned. But they have eitherbeen lost or got dissolved into the presentNatyasastra. The term Natya encompassesin itself all the artistic elements <strong>of</strong> theTheatre Art. Dance was only a part <strong>of</strong>drama in ancient <strong>India</strong>. But drama itselfwas mostly danced. There was hardly anybifurcation between these arts in the trueHindu theatre. Like the Hindu religion, whichis itself a fusion <strong>of</strong> the Aryans’ . Vedicyagna and the non-Aryans’ Agamic puja,the Hindu theatre also took the form <strong>of</strong> ahomogeneous presentation <strong>of</strong> dance anddrama. Dance seems to have been afavourite sport <strong>of</strong> the non-Aryans, whiledrama, with its literary beauty was theAryan’s love. The art <strong>of</strong> dance developedas drama through its getting mingled withthe Aryan culture. Natya was the termwhich indicated this composite whole. Theterm Sangita was always referred to in itstriple aspects viz., Gita (song), Vadya(instrumental music) and Nritta (dance).All the earlier works on Sangita hadchapters on everyone <strong>of</strong> these elements.Natya included these three plus drama too.The Natya sastra is an unsurpassedcompendious work dealing with all theseelements in totality and running to thirtysixchapters. It is highly probable that thiscomposite work was written during thecourse <strong>of</strong> a few centuries, by authors <strong>of</strong>the same pen-name. Hence this work maybe considered as an extraordinarycompilation <strong>of</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> supplementaltreatises on the subject. This clearly provesthe exclusive importance that the nucleus<strong>of</strong> the original treatise on Natya and itsauthor Bharata enjoyed in the ancient Hindusociety.Natya, in its complete form consists <strong>of</strong>music, dance and communication throughexpression. Of these, the second and thirdelements are known as Nritta and Abhinaya,respectively. The Natya- sastra describesall these elements in great detail. Later,authorities like Saarangadeva (12thcentury A.D.) recognised another formcalled Nritya and defined it as arepresentational kind <strong>of</strong> Nritta. ButBharata’s period had the arts <strong>of</strong> only Nrittaand Abhinaya as parts <strong>of</strong> Natya. Nrittacould be handled in two ways, viz., Uddhata(gracefully forceful) and Sukumara(gracefully s<strong>of</strong>t). These obtained thenames <strong>of</strong> Tandava and Lasya perhaps onlyafter Kalidasa’s time. During Bharata’s

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKAperiod, the term Tandava seems to havebeen a synonym <strong>of</strong> Nritta. The Aryans seemto have freely incorporated the art <strong>of</strong> Nrittainto their Natya. Ever since then, Natyawas almost suffused with Nritta. Its actualplace in it is revealed through the study <strong>of</strong>the nature <strong>of</strong> Natya.The goal <strong>of</strong> any Natya is only to createRasa. Rasa is the enjoyment <strong>of</strong> an aestheticbliss’ derived through witnessing or readinga production. The process through whichthis is achieved is the sub- structure <strong>of</strong>the varied rules analytically laid down inthe Natyasastra. The Bhava, i.e. feeling,contained in a situation and the characterinvolved has to be expressed by the actoror the writer, as the case may be, in sucha way that it can be understood by theonlooker or reader. Unless the feelings andideas are communicated, the audiencecannot share those feelings, whichultimately is responsible for evoking Rasa.The art <strong>of</strong> communication is calledAbhinaya. There are four mediums <strong>of</strong>expression available for the artists. Thisanalysis, given in the Natyasastra, is soaccurate and universal that it is valid eventoday, for any production in any part <strong>of</strong>the world. The four Abhinayas are: Angika(physical), Vachika (verbal), Aharya(external) and Satvika. (internal)Angikabhinaya is the art <strong>of</strong> physicalexpression. The entire human body hasbeen analysed in the Natyasastra as Angas(major limbs) and Pratyangas (minor limbs).Later, authorities added to this classificationthe Upangas (subsidiary limbs) which inturn, were divided as those belongingexclusively to the face and those <strong>of</strong> theother limbs <strong>of</strong> the body. Exercises from head4DANCES OF INDIAto foot are prescribed for each limb, basedhighly on kinetic principles. The studentwas expected to master these individualexercises and proceed to practisingcombinations <strong>of</strong> movements <strong>of</strong> variouslimbs.These exercises are to be meaningfullyutilised to convey ideas and more importantthan that, feelings. This is the essence <strong>of</strong>Angika Abhinaya. Physical expression is apart <strong>of</strong> human nature. The connectionbetween the psyche and the physic is sointrinsic, that even the minutest vibration<strong>of</strong> the mind gets easily reflected throughthe body in daily life itself. For instance,nodding the head is part <strong>of</strong> humanbehaviour while reacting. The force, speedand space <strong>of</strong> our pacing also reflect theinner composure and conflicts. The art <strong>of</strong>physical expression is hence beautifullyconceived, classified and codified byBharata, to artistically suit a dramaticrepresentation.Angikabhinaya is <strong>of</strong> two categories. One isthe Padarthabhinaya while the other isVakyarthabhinaya. The former means theexpression <strong>of</strong> word to word meaning, whilethe latter is a communication <strong>of</strong> the generalidea <strong>of</strong> a sentence or even the mood. Forthe actual execution <strong>of</strong> these, threemediums are given, viz., Sakha, Ankura andNritta. Sakha literally means branch; Ankurais sprout while Nritta is dance. Sakhaindicates the availability <strong>of</strong> an entiresystem <strong>of</strong> gesticulation through the hands.A complete language <strong>of</strong> gestures has beenhanded down by generations <strong>of</strong> artistes.These hand gestures are <strong>of</strong> two kinds. Oneis a group <strong>of</strong> Abhinaya Hastas and the otheris a set <strong>of</strong> Nritta Hastas. The former is

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKAsub-divided as Asamyuta (single hand) andSamyuta (combined hand) gestures. TheseAbhinaya Hastas are used to bring out thePadarthabhinaya. The practical application<strong>of</strong> the given set <strong>of</strong> Abhinaya Hastas is calledAnkura. The second group <strong>of</strong> gesturescalled the Nritta Hastasare to be used in Nritta-Dance. These may beused in the art <strong>of</strong>Vakyarthabhinaya. Themost obvious requirementfor the actors was themasteryoverAngikabhinaya for, thismedium <strong>of</strong> expression wasused in full measure inancient Natya. This isnothing short <strong>of</strong>demanding dancing talentin actors. The scenes likeSakuntala watering theplants or the beeharassing her, or evenDushyanta riding thechariot, were all enactedwith suitable gestures andmovements. The Caris andGatis involving the legswere to be used torepresent the variouscharacters and situations.Their combinations calledthe Mandalas were to beused to enact fighting sequences. TheAngaharas which involve the Karanas wereprimarily meant for invoking the blessings<strong>of</strong> the gods and manes in the preliminary<strong>of</strong> the play. They were also to be usedwherever the emotion <strong>of</strong> love dominated.These Angaharas involve hand gestures.5DANCES OF INDIABut the Mandalas are groups <strong>of</strong> dancemovements to be used along with holdingweapons like the bow and arrow. TheNyayas or rules for such a handling arealso laid down. The actors were actuallydancers. All these prove that Natya wasenacted as Nritta in allthe practical sense.Abhinavagupta is <strong>of</strong>the opinion that Natyaand Nritta are notdifferent from eachother from the view <strong>of</strong>actual practice. Ofcourse, unless one isable to comprehendthe nature <strong>of</strong> theNatya <strong>of</strong> those bygonedays, it will notbe possible to digestthe idea <strong>of</strong> the arts <strong>of</strong>drama and dance notbeing different. TheNatya <strong>of</strong> ancient <strong>India</strong>was a wholesomecombination <strong>of</strong> thepresent day play,opera and ballet. Theexacting nature <strong>of</strong> thetalent <strong>of</strong> the artisteswas in the form <strong>of</strong> theirbeing expected tospeak, sing and dance.Bharata hasmentioned only Natya and Nritta, while theclassification and rigid crystallisation <strong>of</strong> theterm Nritya, as understood today is notfound in his work. But Nritta itself can bepresented as representational or nonrepresentational.It can be a part <strong>of</strong> the

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKAactual body <strong>of</strong> the play, or adorn thepreliminary <strong>of</strong> the same. In any case, Nrittawas considered as a limb <strong>of</strong> Natya. In otherwords, it is enlisted under Angikabhinayaby Abhinavagupta, the commentator.Sakha, Ankura and Nritta are the threeelements <strong>of</strong> physical expression. Thismeans that Nritta is the expression <strong>of</strong> ideasthrough the movements <strong>of</strong> the entire ‘body.This aspect <strong>of</strong> Angikabhinaya has gone intooblivion in the course <strong>of</strong> the past four orfive centuries. Angikabhinaya has come tomean the mere art <strong>of</strong> hand gestures basedon the Abhinaya Hastas delineated in a morerecent work, viz., Nandikeswara’s AbhinayaDarpanam. The art <strong>of</strong> using the entire bodyto convey ideas is Nritta according to theBharata tradition. Later, authoritiesclassified Nritya as representational andNritta as non-representational arts. But,Bharata’s Nritta was both re-presentationaland non-representational. It was an art tobe mastered by the actors and dancers.Every major and minor limb was to undergoexercises which were to be practised,independent <strong>of</strong> each other as well as beingwoven into one fabric. These Vyayamasformed the foundation <strong>of</strong> Nritta. The limbs<strong>of</strong> the body are classified as Angas-majorlimbs which include the hand, chest, sides,waist, hands and feet. Upangas are theminor limbs such as the neck, elbows,shoulders, belly, thighs, shanks, knees andheels; the Upangas <strong>of</strong> the face are eyes,eye-brows, nose, lower lip and chin. Later,authorities like Sarangadeva classified thelimbs into three groups as Angas (majorlimbs), Pratyangas (subsidiary limbs) andUpangas (minor limbs). Exercises for each<strong>of</strong> the Angas and Upangas are named anddescribed in the Natyasastra. These are6DANCES OF INDIAso analytical that they almost exhaust thepossibilities <strong>of</strong> human ability. They createan unlimited scope for the artistic use <strong>of</strong>the body. The pedagogy <strong>of</strong> the techniquehas been unfortunately lost along with thetechnique itself. Bharata’s Nritta is no easypath. It cannot lend itself for celebratingArangetrams in six months! It does notallow us to get satisfied with the merefootwork technique <strong>of</strong> the Adavu system<strong>of</strong> Sadir or any other isolated dance style<strong>of</strong> today. The feet are only one <strong>of</strong> theAngas and hence the steps are not theend <strong>of</strong> this demanding style. Every limbhas to be under the control <strong>of</strong> the dancersin the Bharata Nritta. In the process. <strong>of</strong>this achievement, the first stage is thelearning <strong>of</strong> the Vyayarnas which areexercises <strong>of</strong> the Angas and Upangas. Threebasic elements mark the second stage <strong>of</strong>learning the Nritta. These are the Sthanas(postures <strong>of</strong> the body), Nritta Hastas(course <strong>of</strong> movements <strong>of</strong> the arms andhands) and Caris (the specific way <strong>of</strong>moving the leg). Then comes theparticularisation <strong>of</strong> the combinations <strong>of</strong> thethree elements <strong>of</strong> Nritta Hasta, Sthana andCari. Any such single combination is giventhe name Karana. The Natyasastra hasenlisted and enumerated 108 suchcombinations under the name <strong>of</strong> Karanas.The Karanas should be understood as aunit <strong>of</strong> Nritta. The foundation as well asthe pinnacle <strong>of</strong> Bharata’s Nritta is theKarana.Before going into the details <strong>of</strong> theKaranas, it is essential to grasp the concept<strong>of</strong> its elements. Sthana denotes the Sthithior the static aspect. It is the definiteposture <strong>of</strong> the body which decides the

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKAphysical lines and the space the bodyoccupies. These Sthanas depend on thevaried positions <strong>of</strong> the feet. Sthanas arebased on the Padabhedas such as Sarna,Parswa, Tryasra, Ancita, Agratalasanchara,Suci and Kuncita. The Sthanas involve thepositions <strong>of</strong> the entire legs unlike thePadabhedas which involve only the feet.The knees play a prominent role in thisformation. Bharata has mentioned sixSthanas for men in Chapter and three forwomen in Chapter XIII.This does not mean thatthey cannot or should notbe used by the contrarysex. In addition to thesestanding postures, he hasgiven nine sitting postures(Asanas) and six recliningpostures in Chapter XIII.Sarangadeva has given alist <strong>of</strong> fifty Sthanasincluding Desi (Folk, Noveland Exotic) postures. TheSthanas <strong>of</strong> Bharata andSarangadeva do notinvolve the hands. Butlater works like the Naiyasastra Sangraha prescribethe hand gestures for theSthanas. Sthanas orSthanakas, as they are variedly referredto, are in short definite positions <strong>of</strong> thebody in which the legs and hands are tobe moved in a Karana.The second element <strong>of</strong> major importancein a Karana is the Nritta Hasta. Hastas arethe hand gestures which can be broadlyclassified as those <strong>of</strong> communicativesignificance and others <strong>of</strong> mere aesthetic7DANCES OF INDIAvalue. The former is called Abhinaya Hastaand the latter type connected with Nrittais called Nritta Hasta. The Abhinaya Hastasare also <strong>of</strong> two kinds, viz., Asamyuta-singlehand gestures and Samyuta—com- binedhand gestures. Bharata has given a list <strong>of</strong>24 Asamyuta, 13 Samyuta and 30 NrittaHastas. The main difference between theAbhinaya Hasta and Nritta Rasta is in theirstatic and dynamic qualities. The originalform <strong>of</strong> the Abhinaya Hasta is static andinvolves just the fingers.This static form <strong>of</strong> AbhinayaHasta is motivated inseveral ways to bring outseveral ideas. For example,the first Abhinaya Hasta,Pataka literally meaningflag, can be moved invarious ways to depictideas such as you, me, sky,floor, clouds, opening orclosing doors, welcoming ordriving out and many othersuch contrary ideas. Buteach Nritta Hasta has adefinite course <strong>of</strong> actioninvolving the entire armsand not just the palms;thirty such actions aredescribed. These actionsdepend on the four Hasta Karanas (fourways <strong>of</strong> whirling the wrists). The thirtyNritta Hastas are based on such rollingactions <strong>of</strong> the hands and arms. The NrittaHastas <strong>of</strong> Bharata’s period are nowobsolete; only a few are seen scattered inthe various dance styles.The third element that constitutes theKarana is the Cari. It has its roots in Car

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKAwhich means to move one’s self, go, walkor roam about, get diffused and to continueperforming. The term Cari indicates all themeaning given for its root. Bharata definesit as the simultaneous movements <strong>of</strong> thethigh, shank and feet. Hence, the Cari is amovement which causes the action <strong>of</strong> theentire leg. Thirty-two such Caris aredescribed under the classification <strong>of</strong> BhuCari and Akasa Cari. The sixteen Bhu Carisare the movements <strong>of</strong> the feet close tothe ground while the sixteen Akasa Carisare movements, involving leaps, jumps andextensions <strong>of</strong> the leg <strong>of</strong>f the ground. TheseAkasa Caris remind us <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> the Plies<strong>of</strong> the Western Classical Ballet. Hence, itis erroneous on the part <strong>of</strong> some scholarsto assume that <strong>India</strong>n Dance has nomovements involving actions on the air orhaving the extension <strong>of</strong> the thighs. Thiswrong impression is caused by the factthat these Akasa Caris have becomeobsolete in the presently known traditions.The Karana, being a combination <strong>of</strong> Sthana,Nritta Hasta and Cari, is certainly amovement and not a mere pose as normallybeing misunderstood. Karana has its rootin Krn meaning doer, causer, doing,making,producing, helping the act <strong>of</strong> doing and onthe whole, any action. The word Karanaalso suggests the idea <strong>of</strong> being aninstrument, an element and an Anga or part<strong>of</strong> something, and in dance, it is a unit <strong>of</strong>action. We have words like Antahkarana,meaning an inner part, i.e., the conscience.We also have the popular usage like ‘ManasaVaca Karmanaha tridha Karanani’ meaningby the three means <strong>of</strong> thought, word anddeed. Hence, Karana is a means to someend. Karanas are woven to form an8DANCES OF INDIAAngahara (a chain <strong>of</strong> dance movements).The major difference between thetechnique <strong>of</strong> Bharata’s Nritta and that <strong>of</strong>our contemporary Nritta is in the use <strong>of</strong>the legs, space and patterns. Theextension <strong>of</strong> the legs caused by the AkasaCaris have been practically lost. All thepresent styles depend on the foot-worktechnique only. The use <strong>of</strong> the legs fromthe root <strong>of</strong> the thighs down to the toeshas been out <strong>of</strong> vogue for nearly fivecenturies. The various aspects <strong>of</strong> BharataNritta are seen scattered in the so-calledregional styles and very <strong>of</strong>ten seen in theneighbouring cultures <strong>of</strong> Ceylon, Burma andIndonesia. The distinctions <strong>of</strong> the regionaldance styles <strong>of</strong> <strong>India</strong> are because each <strong>of</strong>them has just either retained orconcentrated on the isolated aspects <strong>of</strong>Nritta. The Kathak has the Sarna Sthanaas its main stay, while the Sadir and itssister styles have the Mandala Sthana.The Vaisakha and Vaishnava are seen morein the Kathakali. The Hasta Karanas andsome Nritta Hastas are retained in Manipuriwhile the South has managed to preserveall the Abhinaya Hastas. In the eyes <strong>of</strong>those who have studied the practicalaspects <strong>of</strong> the Naiya sastra, almost anydance style <strong>of</strong> our country reveals a basicunity in the apparent diversity. Almostevery dance movement can be explainedagainst the backdrop <strong>of</strong> the Natyasastra.The unlimited scope <strong>of</strong>fered in this text,when used in practice, gives room forunending variety.The new term Bharata Natyam for the olderterm Sadir has created a fair amount <strong>of</strong>confusion in regard to its antiquity. This

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKAstyle is just one kind <strong>of</strong> Bharata Natyam,if we take the term Bharata Natyam tomean that Natya which follows Bharata’swork. It is partiality to associate the name<strong>of</strong> this great sage with just one <strong>of</strong> thestyles that still retains the traces <strong>of</strong> hisNatyasastra. In fact, the present BharataNatyam is more <strong>of</strong> Nritta and Nritya in itsnature than Natya in its true sense. Everystyle <strong>of</strong> dance has in it some aspect <strong>of</strong>the Natyasastra still lingering. Hence, thevarious styles may be referred to as,Bharata Natyam in Manipuri style,Bharatanatyam in Sadir style,Bharatanatyam in Kathakali style and soon. In the eyes <strong>of</strong> one who has studiedthe Natyasastra all the so-called majordance styles <strong>of</strong> <strong>India</strong> appear like thedifferent shades <strong>of</strong> the same colour. Arewe not used to recognising all the substylessuch as those <strong>of</strong> Thanjavur, Vazhuvur,etc., as Bharatanatyam and the Gharanas<strong>of</strong> Lucknow, Jaipur and others as Kathak?It is only an extension <strong>of</strong> the same. Theevolution <strong>of</strong> the Karanas can be seen in allthese styles. Some examples are thechanged forms <strong>of</strong> Mattalli Karana inKuchipudi, Paraswajanu Udvrittam andMandalaswastikam in Sadir, many <strong>of</strong> theKaranas involving Tribhang in Odissi,Atikranta and Parswakranta in Kathakali,Vartitam in Mohini Attam, Adhyardhika Cariin Manipuri, Karanas involving Bhramarisin Kathak and Vivrttam in Yakshagana. Theuse <strong>of</strong> the entire legs and arms in the Carisand Nritta Hastas give the Karanas definitecharacter. These do differ from theestablished and well-remembered classicaltraditions. It is natural that theperformances <strong>of</strong> these Karanas disturbthose who are soaked in any one <strong>of</strong> the9DANCES OF INDIAmost angular sub-styles <strong>of</strong> the Sadir. Thefact is that Bharata’s Nritta is all embracing.A resurrection <strong>of</strong> the lost technique hasproved that Bharatanatya in its true senseis Bharatiya Natya.Another interesting factor <strong>of</strong> Bharata’sNritta is that it is suitable for both thesexes. The same set <strong>of</strong> 108 Karanas aremeant for both the male and the femaledancers. There are no separate movementsfor Lasya and Tandava. In fact, the termTandava is used only as a synonym <strong>of</strong>Nritta in the Natyasastra. This Tandava iscommon for both the sexes. The chapterdealing with the Karanas is called TandavaLakshanam. The Katanas are called NrittaKatanas. Though their origin is attributedto Lord Siva, it is handled by Parvati Deviand the apsara women too. Hence, wemust realise a basic fact, that though theformat <strong>of</strong> the action are the same, due tothe inherent differences in nature <strong>of</strong> themale and female, the ultimate effect isdifferent when they are performed. Theforceful style <strong>of</strong> presentation is given thename Uddhata and the s<strong>of</strong>t execution <strong>of</strong>the same is called Sukumara. Hence,according to Natya- sastra, Nritta orTandava may be performed as per theUddhata or Sukumara usage. It should alsobe kept in mind that the Uddhata and Sukumarausages are not to be compartmentalisedfor the male and the female dancers.As and when necessity arises, these canbe interchanged in consonance with thecharacter and the situation.Dance, Gymnastics and Acrobatics haveall <strong>of</strong>ten got mixed up in the course <strong>of</strong>their development. This is true <strong>of</strong> the dance<strong>of</strong> every part <strong>of</strong> the world. In fact, some

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA10DANCES OF INDIA<strong>of</strong> the more acrobatic Karanas must beviewed from the point <strong>of</strong> view <strong>of</strong> exerciseand in the case <strong>of</strong> Natya, their proper usein the relevant sequences. For example,the somersault was meant for fightingsequences and certainly not for beingincluded in the Angaharas to represent love.The movements which are more <strong>of</strong>acrobatic nature were actually termed asAdhama-inferior in a later work calledMahabharata Chudamani. The ideal Nrittabut not the least Satvikabhinaya-anoutcome <strong>of</strong> the psychological states <strong>of</strong>mind. Vachikabhinaya includes the dialoguesand songs. It may be prose or poetry. Voicemodulation and its control, playa major rolein this form <strong>of</strong> communication. TheNatyasastra gives even the rules <strong>of</strong>prosody. The language employed is alsoexpected to suit the various characters.All the plays <strong>of</strong> our contemporary theatreseem to utilise only Vachikabhinaya andis that which emanates beauty and joy at that too devoid <strong>of</strong> songs. Thethe various levels <strong>of</strong> human understandingand perceptions such as physical,intellectual, emotional and spiritual.Aharyabhinaya included the specific facialmake-up, colours, crowns, jewelry andcostumes for each character.The level <strong>of</strong> Nritta is directly proportionalto the level <strong>of</strong> the dancer’s realisation <strong>of</strong>her own inner personality; this is quite apartfrom her physical beauty or even skill.Nritta is a spiritual experience for the idealdancer and the ideal audience. It is a meansthrough which the dancer achieves ashedding <strong>of</strong> her body consciousness. As inYoga, in dance too, the body is trainedonly to be forgotten about. The dancer’sself, integrated with the universal dance<strong>of</strong> all the constant Cosmic Activity, liberatesher from all the shackles <strong>of</strong> this earth. Thedancer herself becomes a microcosmicbeing, experiencing within herself unlimitedfreedom and bliss. The result <strong>of</strong> such aNritta is the same as that <strong>of</strong> Yoga andYagna.Apart from the art <strong>of</strong> Angikabhinaya in whichNritta also IS meluded, <strong>India</strong>n theatre haslong recognised the use <strong>of</strong> Vachikabhinayaverbalexpression, Aharyabhinayaexpressionthrough external elements likecostumes, make-up and scenery and lastSatvikabhinaya is perhaps the mostimportant, yet the most difficult mode <strong>of</strong>expression. It cannot be gained throughmere learning or practice. It needs aninnate sense to feel the various situations.It depends on the mental involvement <strong>of</strong>the performer backed by a clear intellectualgrasp <strong>of</strong> the characterisation to beportrayed. Sat literally means ‘mind’. Evenin actual life, it is most natural that theinner feelings get reflected in the face.Apart from the facial expressions, the eightSatvika conditions are said to be stupor,perspiration, horripilation, change <strong>of</strong> voice,trembling, change <strong>of</strong> colour, tears andfainting. The four-fold art <strong>of</strong> Abhinaya canfurther be classified as Natya- dharmi(stylistic) and Lokadharmi (realistic). TheNatya was the combination <strong>of</strong> both thesemodes <strong>of</strong> expression. Natyadharmi pertainsto the conventions <strong>of</strong> the stage. Forexample, walking around the stage maydenote a change <strong>of</strong> place. The use <strong>of</strong>dance in drama is itself Natya- dharmi.The convention in a play, according to

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKAwhich persons are supposed not to hearwords uttered in proximity, or to hear whathas not been uttered at all, are all part <strong>of</strong>Natyadharmi. In this conventional stylisticmode, the actor may dance instead <strong>of</strong>walking. In short, anything which is beyondthe purview <strong>of</strong> realism, but presented inan artistically appealing manner isNatyadharmi. If, on the other hand, theplay depends on natural behaviour,presented as simple acting with n<strong>of</strong>lourishes <strong>of</strong> even physical expression, it iscalled Lokadharmi.A deeper insight into the Natyadharmi andLokadharmi modes reveal that the formeris formal and perhaps easier to be handledwhereas the latter is informal, but requiresa consummate skill, understanding, mentalinvolvement, imagination and sobriety. Theformer can be taught, but the latter hasto be felt and hence it requires an artiste<strong>of</strong> greater experience in communication. Itis also true that Lokadharmi, when treatedwell, is more easily understood even by anuninitiated audience. But the Natyadharmireaches only those who are at least fairlywell versed with the conventions <strong>of</strong> thestage. The use <strong>of</strong> hand gestures is directlyproportional to the degree <strong>of</strong> Natyadharmi.It is interesting to note that Bharata hasstated that in superior persons, handgestures should have scanty movements,in mediocre ones, there should be mediummovements, while in the acting <strong>of</strong> ordinarypersons, there should be pr<strong>of</strong>usemovements <strong>of</strong> hand gestures. But whendifferent occasions or time ‘presentthemselves, wise people should make varieduse <strong>of</strong> the hand gestures. Bharata has alsomentioned that the hand gestures are to11DANCES OF INDIAbe totally discarded when ne has to enactsituations such as fainting, dreaming orbeing terrified, disgusted or overcome bysorrow and so on. Such scenes need to beenacted through Satvikabhinaya.This expression <strong>of</strong> inner feelings withoutthe use <strong>of</strong> gestures is closer to the concept<strong>of</strong> Lokadharmi or realism. Hence thesituations and characters fully charged withemotion are expected to depend only uponSatvikabhinaya in the Lokadharmi style.Bharata’s Natya was a combination <strong>of</strong> boththe stylistic and the realistic modes <strong>of</strong>expression, thus adding to its unendingvariety.Apart from the differences in the modes <strong>of</strong>communication, Natya on the whole, is tobe constructed in one or a mixture <strong>of</strong> thefour styles called Vrittis. They are Bharati,Arabhati, Satvati and Kaisiki. Here they areinterpreted from a practical point <strong>of</strong> view.Bharati is the verbal style, depending mainlyon the beauties <strong>of</strong> Vachikabhinaya. Use <strong>of</strong>flowery language as well as the slangsuitable for the specific characters are themain features <strong>of</strong> this Vritti. The merereading <strong>of</strong> the play itself must be satiatingin the Bharati Vritti. Language and dictionwith proper voice modulation mark thestrength <strong>of</strong> this style. Arabhati Vritti is theforceful style characterised by apredominance <strong>of</strong> combats, arousing thepsychological states <strong>of</strong> fury, hatred andwonder. The combats are to be performedthrough the use <strong>of</strong> Mandalas. Hence itinvolves a fair amount <strong>of</strong> Natyadharmi withAngik- abhinaya <strong>of</strong> the Uddhata or forcefulnature. It also needs pageantry andglamour through elaborate scene settings,

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKAcostumes and make-up. HenceAharyabhinaya plays a major role in theArabhati Vritti. Satvati Vritti depends mainlyon the strength <strong>of</strong> the emotional content.The main feature are the moulding <strong>of</strong> thecharacters, and story with enough scopefor Satvikabhinaya. This naturally amountsto a greater use <strong>of</strong> Lokadharmi with only alittle use <strong>of</strong> gestures. Satvati has beentranslated as the ‘Grand Style’. Perhapsthis description suits the glamour <strong>of</strong> theArabhati style. Sat denotes psyche andhence Satvati Vritti may be understood asthe emotional style, whereinSatvikabhinaya dominates. Satvika alsodenotes the Satvaguna-the superiorqualities <strong>of</strong> human thought and itsconsequential behaviour, the other qualities<strong>of</strong> a relatively lower gradation beingRajoguna and Tamoguna. The play inSatvati Vritti is expected to portraycharacters <strong>of</strong> higher qualities. Even if thereare sequences <strong>of</strong> fights and personalcombats, they must be based on theNyayas (strict adherence to the properrules). Of course, the essence <strong>of</strong> all <strong>India</strong>nplays is the victory <strong>of</strong> the good over theevil. The Satvati Vritti needs to suppresseven sorrow. This style, on the wholeshould be taken to require subdued acting(without being demonstrative) with arealistic expression <strong>of</strong> feelings andconcepts <strong>of</strong> a superior nature.The Kaisiki Vritti is different from the SatvatiVritti in its Natya- dharmi character. Kaisikineeds delicate emotions like, love,portrayed through Angikabhinaya. It needsthe support <strong>of</strong> glittering costumes, lil- tingmusic and cultivated dance, all meltingtogether to make an amalgam <strong>of</strong>12DANCES OF INDIApleasantness. It needs beautiful women,like the heavenly damsels, the Apsaras.They are said to have been created byLord Brahma to fulfil the requirement <strong>of</strong>this Vritti. It is likely that it is the concept<strong>of</strong> Apsaras that gave to the <strong>India</strong>n stagethe Kaisiki Vritti itself. This idea <strong>of</strong> femininegrace-Lasya-which has come down to thisday is certainly a product <strong>of</strong> the influence<strong>of</strong> these imaginative dancing demigoddesses.The Kaisiki Vritti is still seenhaving its sway in the <strong>India</strong>n movies whereinthe heroine is unhesitatingly portrayed assinging and almost dancing the patheticsongs, even when portraying thecontemporary society. The stylism in the<strong>India</strong>n movie is the result <strong>of</strong> its inheritancefrom the traditional <strong>India</strong>n theatre. Theolder Tamil dramas <strong>of</strong> this century were,and are still marked by a pr<strong>of</strong>use use <strong>of</strong>music. Such musical dramas <strong>of</strong> Tamilnaduhave their own parallels in other parts <strong>of</strong>our country.The most amazing fact is the permanentvalue <strong>of</strong> Bharata’s analysis andclassifications <strong>of</strong> the art <strong>of</strong> dramaticpresentation. The ideas <strong>of</strong> the four modes<strong>of</strong> communication, realism, stylism and thefour basic styles <strong>of</strong> the theatre art holdgood, for any part <strong>of</strong> the world and at anypoint <strong>of</strong> time. Almost any production can.be analysed against this basic backdrop <strong>of</strong>the Natyasastra.The Natyasastra does not stop with themere analysis <strong>of</strong> the Vrittis. It has alsogiven advice to artistes regarding thechoice <strong>of</strong> the specific styles, in a pure ormixed fashion· to suit the taste <strong>of</strong> theaudience <strong>of</strong> the various regions. These arebroadly classified under four Pravrittis,

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKAtaking geographic divisions intoconsideration. These are calledDakshinatya, Avanti, Odramagadhi andPanchali. The geographical namesmentioned in the Natyasastra with regardto these Pravrittis are met with in thePuranas. The Dakshinatya Pravritti pertainsto the land south <strong>of</strong> the Vindhya mountainsand uses the Kaisiki Vritti. Avanti belongsto the western region and makes use <strong>of</strong>the Kaisiki and Satvati Vrittis. Odramagadhiis meant for the eastern region includingNepal and is expected to use the Kaisikiand Bharati Vrittis. Panchali is with regardto the northern region; For this the Satvatiand Arabhati Vrittis are recommended.Combinations in varying degrees <strong>of</strong> thedifferent elements <strong>of</strong> Naiya like the fourAbhinayas, the two Dharmis and the fourVrittis with all the aspects <strong>of</strong> Sangita viz.,Gita, Vadhya and Nritta gave rise to anumber <strong>of</strong> major and minor types <strong>of</strong> drama.These were the Rupas or Rupakas, and theUparupakas respectively. Bharata mentionsonly the ten major Rupas. Later historyshows that many minor plays calledUparupakas were developed as dance andmusic dramas. All the present operatic,dramatic and dance forms can be studiedin relation to the older Rupakas andUparupakas.In this context, the dance known asBharatanatyam today, is neither Naiya inits true sense nor does it faithfully followBharata. It has the aspects <strong>of</strong> Nritta andPadarthabhinaya performed mostly as solodance. In fact, it is closer to the concept<strong>of</strong> Lasya as found in the Naiya-sastra.Lasya, according-to Bharata’s work,includes a set <strong>of</strong> songs or verses to be13DANCES OF INDIAsung or recited by a solo female dancer.These are at least somewhat similar to thegeneral format <strong>of</strong> the present Bharatanatyam.But this Lasya <strong>of</strong> Bharata’s workis only one <strong>of</strong> the sparks from the greatfire <strong>of</strong> Natya which was <strong>of</strong> a majorcomposite structure. Except the AbhinayaHastas, the present Bharatanatyam hasnot retained many <strong>of</strong> the intricacies <strong>of</strong> evenBharata’s Nritya and Abhinaya.There are other dramatic forms· which areclose to Bharata’s Natya in their conceptionif not in their technique. The Therukkoothuand Bhagavatamela <strong>of</strong> Tamilnadu, Koodiattamand Chakkiarkoothu <strong>of</strong> Kerala, theBhagavata Atta <strong>of</strong> Kuchipudi and <strong>of</strong> othersimilar villages <strong>of</strong> Andhra, and theYakshagana <strong>of</strong> Karnataka, are some <strong>of</strong> thetheatrical forms which show an underlyingunity in their format in spite <strong>of</strong> theirlinguistic diversity. All these forms aredescendants <strong>of</strong> Bharata’s Natya and henceall the four Abhinayas play an equal role inthem. The artistes are expected to speaksing and dance. Mime plays a major role inthem. The songs are in the local languages.But the general character <strong>of</strong> these playsis highly unified. There is a striking similarityeven in their Aharya. The large crowns thejewels, their shoulder pieces and the makeuphave a striking similarity. The charactersare represented with their suitable Gatis(gaits) along with the songs called Darus.The origin <strong>of</strong> the Daru can be traced in theDruva, a musical form mentioned in theNatyasastra. The types <strong>of</strong> Darus arecommon to all these. Only their names andmetres change. The Sutradhara (thedirector <strong>of</strong> the play) introduces the play inthe prologue. He is called the Kattiyakkaran

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKAin Tamil. The Tiraisilai (the hand-heldcurtain) is used in all these forms tointroduce major characters. Except theKoodiattam, all these other theatre formsare enacted only by male artistes.14DANCES OF INDIABharata’s tradition. Hence, like a livinglanguage, the performing arts <strong>of</strong> <strong>India</strong> havealso been undergoing changes constantly.This does not mean that they ever losttheir roots at any point <strong>of</strong> time.Bharata’s Natya is so comprehensive thatits elements are invariably met with in ascattered manner, even in the remotestcorners <strong>of</strong> our country. Its compendiousnature is a testimony to the unparalleledartistic and intellectual synthesis <strong>of</strong> ancient<strong>India</strong>n theatre. With the help <strong>of</strong> this Sastra,we are able to analyse and appreciate anytheatrical form <strong>of</strong> the world. It is amazinghow this art had been fully developed in allthe possible aspects, even at a period whensome parts <strong>of</strong> the world were still sleepingin the cradle <strong>of</strong> civilisation. The unlimitedscope it <strong>of</strong>fers for creativity, in spite <strong>of</strong>recording even the minutest detail <strong>of</strong> theart <strong>of</strong> action and acting, speaks for theunending variety <strong>of</strong> interpretation, thatgenerations <strong>of</strong> artistes have been able toconceive for the same rules.The general impression <strong>of</strong> some scholarsthat <strong>India</strong>n theatre <strong>of</strong>fers no scope forcreativity and imagination is actuallybaseless. The Natya- sastra and othertexts are like grammar and the artistes whohandle them are like poets. The freedomwhich poets have within the frame-work<strong>of</strong> the rules <strong>of</strong> grammar and prosody, iscertainly enjoyed by the actors anddancers. The terms Margi and Desi in bothmusic and dance signified the older andnewer forms. As centuries passed, thespontaneous creativity <strong>of</strong> the artistes <strong>of</strong>various regions were also codified underthe name <strong>of</strong> ‘Desi’; ‘Margi’ signifiedThe <strong>India</strong>n artiste finds audience <strong>of</strong> thelevel <strong>of</strong> appreciation which is equal to herown mental calibre. After all, Natya is saidto yield all the fruits <strong>of</strong> life-Dharma, Artha,Kama and Moksha. Hence the artistes havebeen and are still serving as poets, usingthe rules laid down in the Sastras to createtheir own worlds <strong>of</strong> art.Bharata’s Natya has its deep roots in everypart <strong>of</strong> our country. It has also spread itsprinciples at all the levels <strong>of</strong> appreciation.Natya is an imitation <strong>of</strong> the three worldsand hence all types <strong>of</strong> characters areincluded in it. It has always had theresponsibility and capacity to satisfy people<strong>of</strong> various tastes. In spite <strong>of</strong> laying thequalities <strong>of</strong> even an ideal spectator,Bharata says that the inferior and commonpersons in an assembly which consists <strong>of</strong>the superior, the middling and the inferiormembers, cannot be expected toappreciate the performance <strong>of</strong> the superiorones. And hence an individual to whom aparticular dress, pr<strong>of</strong>ession, speech andan act belong as his own, should beconsidered fit for appreciating the same.That is why we need Sahrdaya (audience<strong>of</strong> equal mental calibre) to make theperformance <strong>of</strong> Natya a real success. Aswater finds its own level, Natya too findsits own audience at various planes <strong>of</strong>human perception.

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA15The Dance Of ShivaDANCES OF INDIAANANDA K. COOMARASWAMYThe Lord <strong>of</strong> Tillai’s Court a mysticdance performs; What’s that, mydear?”- Tiruvachagam,XII.14Amongst the greatest <strong>of</strong> the names <strong>of</strong>Shiva is Nataraja, Lord <strong>of</strong> Dancers, or King<strong>of</strong> Actors. The Cosmos is His theatre. Thereare many different steps in His repertory.He Himself is actor and audience-When the Actor beats the drum,Everybody comes to see the show;When the Actor Collects the stagepropertiesHe abides alone in His happiness.How many various dances <strong>of</strong> Shiva areknown to His worshippers I cannot say. Nodoubt the root idea behind all these dancesis more or less one and the same, themanifestation <strong>of</strong> primal rhythmic energy.Shiva is the Eros Protogonos <strong>of</strong> Lucian,when he wrote:“It would seem that dancing came intobeing at the beginning <strong>of</strong> all things, andwas brought to light together with Eros,that ancient one, for we see this primevaldancing clearly set forth in the choraldance <strong>of</strong> the constellations, and in theplanets and fixed stars, their inter-weavingand interchange and orderly harmony”.I do not mean to say that the mostpr<strong>of</strong>ound interpretation <strong>of</strong> Shiva’s dancewas present in the minds <strong>of</strong> those wh<strong>of</strong>irst danced in frantic, and perhapsintoxicated energy, in honour <strong>of</strong> the pre-Aryan hill-god, afterwards merged in Shiva.A great motif in religion or art, any greatsymbol, becomes all things to all men; ageafter age it yields to men such treasuresas they find in their own hearts. Whateverbe the origin <strong>of</strong> Shiva’s dance, it becamein time the clearest image <strong>of</strong> the activity<strong>of</strong> god which any art <strong>of</strong> religion can boast<strong>of</strong>. Of the various dances <strong>of</strong> Shiva, I shallonly speak <strong>of</strong> three, one <strong>of</strong> them aloneforming the main subject <strong>of</strong> interpretation.The first is an evening dance in theHimalayas, with a divine chorus describedas follows in the Shiva Pradosha Stotra:“Placing the Mother <strong>of</strong> the Three Worldsupon a golden throne, studded withprecious gems, Shulapani dances on theheights <strong>of</strong> Kailasa, and all the gods gatherround Him:“Saraswati plays on the Vina, Indira onthe flute, Brahma holds the time-markingcymbals, Lakshmi begins a song, Vishnuplays on a drurn, and all the gods standround about:“Gandharvas, Yakshas, Patagas, Uragas,Suddhas, Sadhyas, Vidyadharas, Amaras,Apsarasas, and all the beings dwelling inthe three worlds assemble there to witnessthe celestial dance and hear the music <strong>of</strong>the divine choir at the hour <strong>of</strong> twilight”.Thisevening dance is also referred to in theinvocation preceding the Katha SaritSagara.

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKAIn the pictures <strong>of</strong> this dance, Shiva is twohanded,and the co-operation <strong>of</strong> the godsis clearly indicated in their position <strong>of</strong>chorus. There is no prostrate Asuratrampled under Shiva’s feet. So far as Iknow, no special interpretations <strong>of</strong> thisdance occur in Shaiva literature.The second well-known dance <strong>of</strong> Shiva iscalled Tandava and belongs to His tamasicaspect as Bhairava or Virabhadra. It isperformed in cemeteries and burninggrounds, where Shiva, usually ten-armedform, dances wildly with Devi, accompaniedby troupes <strong>of</strong> capering imps.Representations <strong>of</strong> this dance are commonamongst ancient sculptures, as at Ellora,Elephanta, and also Bhuvaneshvara. TheTandava dance is in origin that <strong>of</strong> a pre-Aryan divinity, half-god, half-demon, whoholds his midnight revels in the burningground. In later times, this dance in thecremation ground, sometimes <strong>of</strong> Shiva,sometimes <strong>of</strong> Devi, is interpreted in Shaivaand Shakta literature in a most touchingand. pr<strong>of</strong>ound sense.Thirdly, we have the Nadanta dance <strong>of</strong>Nataraja before the assembly (sabha) inthe golden hall <strong>of</strong> Chidambaram or Tillai,the Centre <strong>of</strong> the Universe, first revealedto gods and rishis after the submission <strong>of</strong>the latter in the forest <strong>of</strong> Taragam, asrelated to the Koyil Puranam. The legend,which has after all, no very closeconnection with the real meaning <strong>of</strong> thedance, may be summarised as follows:In the forest <strong>of</strong> Taragam dwelt multitudes<strong>of</strong> heretical rishis, following <strong>of</strong> the Mimamsa.Thither proceeded Shiva to confute themaccompanied by Vishnu disguised as a16DANCES OF INDIAbeautiful woman, and Adi-Shesha. Therishis were at first led to a violent disputeamongst themselves, but their anger wassoon directed against Shiva, and theyendeavoured to destroy Him by means <strong>of</strong>incantations. A fierce tiger was created insacrificial fires, and rushed upon Him; butsmiling gently, He seized it, and, with thenail <strong>of</strong> His little finger, stripped <strong>of</strong>f its skin,and wrapped it about Himself like a silkencloth. Undiscouraged by failure, the sagesrenewed their <strong>of</strong>ferings, and produced amonstrous serpent, which, however, Shivaseized and wreathed about His neck like agarland. Then He began to dance; butthere rushed upon Him a last monster inthe shape <strong>of</strong> a malignant dwarf, Muyalaka.Upon Him the god pressed the tip <strong>of</strong> Hisfoot, and broke the creature’s back, sothat it writhed upon the ground; and so,His last foe prostrate, Shiva resumed thedance witnessed by gods and rishis.Then Adi-Shesha worshipped Shiva, andprayed above all things for the boon, oncemore to behold this mystic dance; Shivapromised that he should behold the danceagain insacred Tillai, the centre <strong>of</strong> theUniverse.This dance <strong>of</strong> Shiv a in Chidambaram orTillaiforms the motif <strong>of</strong> the South <strong>India</strong>n copperimages <strong>of</strong> Shri Nataraja, the Lord <strong>of</strong> theDance. These images vary amongstthemselves in minor details, but all expressone fundamental conception. Beforeproceeding to enquire what these may be,it will be necessary to describe the image<strong>of</strong> Shri Nataraja as typically represented.The images, then, represent Shiva dancing,having four hands, with braided and jewelledhair <strong>of</strong> which the lower locks are whirling

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKAin the dance. In His hair may be seen awreathing cobra, a skull, and the mermaidfigure <strong>of</strong> Ganga ; upon it rests the crescentmoon and it is crowned with a wreath <strong>of</strong>Cassia leaves. In hisright ear, He wearsa man’s ear-ring, awoman’s in the left;He is adorned withnecklaces andarmlets, a jewelledbelt, anklets,bracelets, fingerand toe rings . Thechief part <strong>of</strong> Hisdress consists <strong>of</strong>tightly fittingbreeches, and Hewears also afluttering scarf anda sacred thread.One right handholds a drum, theother is up- lifted inthe sign <strong>of</strong> do notfear: one left handholds fire, the otherpoint’; down uponthe demonMryalaka, a dwarf holding cobra ; the leftfoot is raised, There is a lotus pedestal,from which springs an encircling glory(tiruvasi), fringed with flame, and touchedwithin by the hands holding drum and fire.The images are <strong>of</strong> all sizes, rarely if everexceeding four feet in total height.Even without reliance upon literaryreference, the interpretation <strong>of</strong> this dancewould not be difficult. Fortunately,however, we have the assistance <strong>of</strong> a17DANCES OF INDIAcopious contemporary literature, whichenables us to fully explain not only thegeneral significance <strong>of</strong> the dance, butequally, the details <strong>of</strong> its concretesymbolism. Some <strong>of</strong>the peculiarities <strong>of</strong>the Nataraja images,<strong>of</strong> course, belong tothe conception <strong>of</strong>Shiva generally, andnot to the dance inparticular. What is themeaning <strong>of</strong> Shiva’sNadanta dance, asunderstood byShaivas? Its essentialsignificance is givenin texts such as thefollowing:“Our Lord is theDancer, who, like theheat latent infirewood, diffuses Hispower in mind andmatter, and makesthem dance in theirturn.” [KadavulMamunivar’sTiruvatavurar Puranam, Puttaraivatil,Venracarukkam, stanza 75, translated byNallaswami Pillai, Shivajnanabodham, p. 74.]The dance, infact, represents His fiveactivities (Panchakritya), viz: Srishti(overlooking, creation, evolution), Sthiti(preservation, support), Samhara(destruction, evolution), Tiro-bhava(veiling, embodiment, illusion and also givingrest), Anugraha (release, salvation, grace).These, separately considered, are theactivities <strong>of</strong> the deities Brahma, Vishnu,

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKARudra, Maheshwara and Sadashiva.The cosmic activity is the central motif <strong>of</strong>the dance. Further quotations will illustrateand explain the more detailed symbolisms.Unmai Vilakkam, verse 36, tells us:18DANCES OF INDIAdesolate. The place where the ego isdestroyed signifies the state where illusionand deeds are burnt away: that is thecrematorium, the burning ground where ShriNataraja dances, and whence He is namedSudalaiyadi, Dancer <strong>of</strong> the burning-ground.In this simile, we recognise the historicalconnection between Shiva’s gracious danceas Nataraja, and His wild dance as thedemon <strong>of</strong> the cemetery.This conception <strong>of</strong> the dance is currentalso amongst Shaktas, especially in Bengal,where the Mother rather than the Fatheraspect<strong>of</strong> Shiva is adored. Kali is here thedancer, for whose entrance the heart mustbe purified by fire, made empty byrenunciation.We find in Tamil texts, the purpose <strong>of</strong> Shiva’sdance explained. In Shivajnana Siddhar,Supaksha, Sutra, V, 5, we find:“Creation arises from the drum: protectionproceeds from the hand <strong>of</strong> hope: from fireproceeds destruction: the foot held al<strong>of</strong>tgives release”. It will be observed that thefourth hand points to this lifted foot, therefuge <strong>of</strong> the soul.Shiva is a destroyer and loves the burningground. But what does He destroy? Notmerely the heavens and earth at the close<strong>of</strong> a world-cycle, but the fetters that bindeach separate soul. Where and what isthe burning ground? It is not the placewhere our earthly bodies are cremated, butthe hearts <strong>of</strong> His lovers, laid waste and“For the purpose <strong>of</strong> securing both kinds <strong>of</strong>fruit to the countless soul, our Lord, withactions, five, dances His dance”. Both kinds<strong>of</strong> fruit, that is Iham, reward in this world,and Param, bliss in Mukti.The conception <strong>of</strong> the world process asthe Lord’s pastime or amusement (lila) isalso prominent in the Shaiva scriptures.Thus Tirumular writes, “The perpetualdance is His play”. This spontaneity <strong>of</strong>Shiva’s dance is so clearly expressed inSkryabin’s Poem <strong>of</strong> Ecstasy.This aspect <strong>of</strong> Shiva’s immanence appearsto have given rise to the objection that hedances as do those who seek to pleasethe eyes <strong>of</strong> mortals; but it is answeredthat in fact He dances to maintain the life<strong>of</strong> the cosmos and to give release to those

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKAwho seek Him. More over, if we understandeven the dances <strong>of</strong> human dancers rightly,we shall see that they too lead to freedom.But it is nearer the truth to answer thatthe reason for His dance lies in His ownnature, all His gestures are own-natureborn (svabhavajah), spontaneous andpurpose less for His being is beyond therealm <strong>of</strong> purposes.In a much more arbitrary way, the dance<strong>of</strong> Shiva is identified with the Panchakshara,or five syllables <strong>of</strong> the prayer Shi-va-yana-ma‘Hail to Shiva’. In Unmai Vilakkamwe are told: “If this beautiful Five-Lettersbe meditated upon, the soul will reach theland where there is neither light nordarkness, and there Shakti will make it Onewith Shivam” [Nandikeshvara, The Mirror<strong>of</strong> Gesture, translated by Coomaraswamyand Dug- girala, p .11.]The Tiru-Arul-Payan however (Ch. IX. 3)explains the tiruvasi more naturally asrepresenting the dance <strong>of</strong> Naturecontrasted with Shiva’s dance <strong>of</strong> wisdom.“The dance <strong>of</strong> nature proceeds on one side:the dance <strong>of</strong> enlightenment on the other.Fix your mind in the centre <strong>of</strong> the latter”.Now to summarize the whole interpretationwe find that the essential significance <strong>of</strong>Shiva’s dance is three-fold: First, it is theimage <strong>of</strong> his rhythmic playas the source <strong>of</strong>all movement within the Cosmos, which isrepresented by the Arch: Secondly, thepurpose <strong>of</strong> His dance is to release thecountless souls <strong>of</strong> men from the snare <strong>of</strong>19DANCES OF INDIAIllusion: Thirdly, the place <strong>of</strong> the dance,Chidambaram, the Centre <strong>of</strong> the Universe,within the Heart. So far I have refrainedfrom all aesthetic criticism and haveendeavoured only to translate the centralthought <strong>of</strong> the conception <strong>of</strong> Shiva’s dancefrom plastic to verbal expression, withoutreference to the beauty or imperfection <strong>of</strong>individual works. But it may not be out <strong>of</strong>place to call attention to the grandeur <strong>of</strong>this conception itself as a synthesis <strong>of</strong>science, religion and art. How amazing therange <strong>of</strong> thought and sympathy <strong>of</strong> thoserishi-artists who first conceived such atype as this, affording an image <strong>of</strong> reality,a key to the complex tissue <strong>of</strong> life, a theory<strong>of</strong> nature, not merely satisfactory to asingle clique or race, nor acceptable tothe thinkers <strong>of</strong> one century only, butuniversal in its appeal to the philosopher,the lover, and the artist <strong>of</strong> all ages and allcountries. How supremely great in powerand grace this dancing image must appearto all those who have striven in plasticforms to give expression to their intuition<strong>of</strong> Life !It is not strange that the figure <strong>of</strong> Natarajahas commanded the adoration <strong>of</strong> so manygenerations past; familiar with allscepticisms, expert in tracing all beliefs toprimitive superstitions, explorers <strong>of</strong> theinfinitely great and infinitely small, we areworshippers <strong>of</strong> Nataraja still.Source: «The Dance <strong>of</strong> Shiva”, Page 66-79 Published by Sagar Publications, 72.Janpath, Ved Mansion, New Delhi - 1.

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA20The Gift Of TraditionK. S. RAMASWAMI SASTRIDANCES OF INDIAAll over the world we have crudefolk dances as well as classicaldance. We find the figures <strong>of</strong>dancing women in the ruins <strong>of</strong> Harappaand Mohanjo Daro. In the Rigveda, GoddessUshas (Dawn) is described as clad in gaygarments, like a dancer. God Siva asNataraja and Goddess Uma are said to havetaught respectively Tandava (the vigorousmasculine type <strong>of</strong> dance) to the sage Tanduand through him to Bharata and others,and Lasya (the graceful feminine type <strong>of</strong>dance) to Bharata and others. In theAbhinaya Darpana <strong>of</strong> Nandikeswara, we findthe famous verse:Angikam Bhuvanam TasyaVaachikam Sarvaangmayah /Aahaaryam ChandrataaraadiTam nu tvah saatvikam Shivam / /sage Bharadwaja’s ashrama (hermitage).Valmiki describes Swayamprabha’s friendHema as Nritta Gita Visarada (Expert indance and music). In Ravana’ s harem therewere similar experts as Nritta VaditraKusalah (Sundara kanda, X 32). In theMahabharata we are told that Arjuna learntdance from the celestial maiden Uma andtaught it to princess Uttara Panini (500B.C.) refers to Natasutras. Queen Mira Bai’sdevotional dances are well-known.]ayadeva’s Gita Govinda was interpretedby the dances <strong>of</strong> his wife Padmavati. Dancewent into the hands <strong>of</strong> courtesans forcenturies but now it has been taken upenthusiastically by family women and isuniversally popular.(The world is the movement <strong>of</strong> His limbs;all speech is His Voice; the moon andthe stars are His decorative ornaments.Let us pray to the good God Siva). Thecosmic dance (tandava) <strong>of</strong> God Siva is<strong>of</strong> seven kinds and symbolises theAnavarata or eternal dance and thedances <strong>of</strong> creation and preservation anddestruction and obscuration and grace(Panchakritya or five divine acts) andthe dance <strong>of</strong> bliss (Ananda Tandava).There is also another classification asAnanda Tandava, Uma Tandava, SivagauriTandava, Kalika Tandava, TripuraTandava and Samhara Tandava. In theRamayana <strong>of</strong> Valmiki, we find the dances<strong>of</strong> the celestial apsaras, maidens in the

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA21DANCES OF INDIALiterature GaloreBharata’s Natya Sastra is the Bible <strong>of</strong> <strong>India</strong>naestheticians. It says that the Creator(Brahma) created it to give joy in life tothe gods who found their cosmic functionsto be heavy and dreary. Bharatarmada andAbinaya Darpana are other importantclassical works on the <strong>India</strong>n art <strong>of</strong> dance.Kalidasa’s drama Malavikagnimitra throwsmuch light on the art and show showprincess Malavika was an expert in it.Vishnu Dharmothara and Agni Purana throwmuch light on the art. Other importantSanskrit works are Dhananjaya’s DasaRoopaka, Sargadava’s Sangita Ratnakara,Thulajaji’s Sangita Saramitra, BalaRamavarma’s Bala Bharata, Haripala Deva’sSangita Sudhakara, Veda Suri’s SangitaMakaranda, Rasamanjari etc.Tamil literature is described as consisting<strong>of</strong> Iyal (poetry) and Isai (music) andNatakam or Koothu (Dance). Of the manyancient Tamil works on dance only BharataSenapatheeyam is extant. BharataSiddhanta, Bharata Sangraha andMahabharata Choodamani are recentworks. In the famous Tamilepic Silappadikaram wehave many great ideasrelating to the art. Thereis a reference to elevenvarieties <strong>of</strong> dance ( alliyam,Kudai, Kudam etc). Itrefers to 24 kinds <strong>of</strong>abhinayam, KambaRamayana refers to adance hall calledAdumantapa Balakanda,Nagarapadalam stanza62). 108 Kananasor danceposes are beautifully sculptured in thegopuram at Chidambaram. There is a danceplatform in front <strong>of</strong> the great temple atTanjore. There are innumerable Tamil andTelugu and Canarese amorous anddevotional songs (padams) composed forinterpretation by dances.The Tamil word Nattuvangam means theart <strong>of</strong> teaching dance, and Nattuvanarmeans dance-teacher.Two beautiful verses in Abhinaya Darpanagive us the very quintessence <strong>of</strong> theteaching as well as the learning <strong>of</strong> the<strong>India</strong>n art <strong>of</strong> Dance.KanthenaambayedgeetamHastenaartham Pradarshayet /Chakshubhyaam darsayedbhauamPaadaabhyaam taalamaacharet //(Sing with the mouth and show themeaning by the gesture <strong>of</strong> the hand andreveal the emotion (bhava) by the eyesand gently beat time with the feet).

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKATato hastastato drishtir-Yato drishtistato manah /Yato manastato VaachahTato Vaachastato Rasah //22DANCES OF INDIA(The eyes follow the hand, the mind followsthe eyes, the bhava follows the mind, andthe rasa follows the bhava).Gitaavaadyatalaanuvartini /(The dance must accompany the vocalsong and the instruments). It is thus clearthat the speechless eloquence <strong>of</strong> the eyesintensifies the beauty <strong>of</strong> the gestures androuses the inner feeling (bhava) to theblossomed state <strong>of</strong> aesthetic emotional bliss(rasa).It is <strong>of</strong>ten said that Bharata Natyam ismeant to be performed only by women. Inrecent times, Uday Shankar and Ramgopaland others have learnt and exhibited it.But Lasya or the graceful form <strong>of</strong> dance ismore appropriate for women than for men.There is a view that it is suited to womenand not to girls because Sringara bhava(the emotion <strong>of</strong> love) cannot be understoodby girls. But the essence <strong>of</strong> the dancebeing devotion or divine love expressed interms <strong>of</strong> human love, the charm <strong>of</strong> thedance depends on naturalness andsincerity which are clouded in adolescentand adult human beings by egoism andegotism and a desire to excel and shine.Variations in GestureIn classical aesthetic terminology, Nrittameans pure dance without reference toany theme or emotion. Nritya is dancewhich expounds emotion by gestures.Natya adds a story element to it. Abhinayais the interpretation <strong>of</strong> emotion by gestures(angika) , by voice (vacheka), by dressand decoration (tapery) and by physicalmanifestations (sattvika). Anyadbhavasrayamnrittam nirityamtalarasasrayam. Gestures can be by thelimbs (anga, pratyanga, and upanga). Theycan be shown by a single hand (asamyuta)or by both hands (samyuta). Tamilnadu isrich in the variety <strong>of</strong> folk dances as well asin the classical art <strong>of</strong> dance. Thedescriptions Marga and Desi refers toclassical dances and regional folk dancesrespectively. The Kummi and Kolattam andPinnal Kolattam dances by the girls <strong>of</strong> theTamilnadu are danced in lovely rhythmicpatterns in which songs beautifymovements and movements beautifysongs. They are not mere crude movements

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA<strong>of</strong> the limbs out <strong>of</strong> exuberance <strong>of</strong> animalspirits because in that case they would bedance but not art. Nor are they soelaborate and controlled by rules asBharata Natya. The Bhajan dances <strong>of</strong>trained religious singers and dancers aremidway between folk-music and folk-danceon the one hand and elaborate Carnaticmusic and Bharatanatyam on the otherhand. On the other hand, oyilattam,chakhaiattam, kauadi dances, karagamdances, dummy horse (poikal kuthirai)dances, theru koothu (street drama)dances by hill tribes, gypsy dances etc.are folk arts pure and simple. ButBommalattam (puppet-shows) is anartistic achievement. The puppets aremoved by strings tied to the limbs <strong>of</strong> theartist behind the curtain. The songs <strong>of</strong> thesingers and the movements <strong>of</strong> the puppetssynchronise superbly. When I was young Isaw Harischandra’s story in Bommalattam.It was attended by thousands night afternight and it made a pr<strong>of</strong>ound impressionon my mind. The introductory dance bythe Kinchin bommai (puppet) was as lovelyas a Bharata Natyam dance. What is calledPavaikoothu (puppet-dance) in ancientTamil literature shows the antiquity <strong>of</strong> theart. In Andhra we have the TholBommalatta (painted leather piecesoperated with bamboo sticks and seenthrough a semi-transparent screen lightedfrom behind). In the Malabar, shadow playfigures are shown by perforating holes onsquare pieces <strong>of</strong> flat leather.Folk-<strong>Dances</strong>The Tamil literature--especially the greatepic Silappadtkaram-refers to other dancessuch as alliyam, kudam, kodukoti, etc.23DANCES OF INDIAThey are not now extant. It refers also toAyar koothu (dances by shepherds),Kuravai koothu (dances by kuravans) etc.They are obsolete. But what is calledkuravanji has been lifted to the highestlevel <strong>of</strong> art by the genius <strong>of</strong> poets. In it, ahuman heroine loves a king or a god andgypsy goes to her and foretells her goodfortune. The Kutrala Kuravanji SarfojiKurauanji, Viralimalai Kurauanji and AehagarKuravanji are fine works <strong>of</strong> art and giveroom for fine ballet dances which are notmere folk-dances but are fine artisticperformances. I must refer also to a newaesthetic creation viz.Chchaya Natakas(Nizhal Attam in Tamil) or shadow-playsby the great artistic geniuses Sri UdayShankar and his wife Srimathi AmalaShankar. In them, the acting is by humanbeings but the public see only the shadowsthrown on a gigantic screen from the otherside <strong>of</strong> the screen. They have nowpresented the Ramayana and the BuddhaCharita.Thus we have in the above dances, bothpure folk dances as well as artistic danceperformances in which the art elementblends with the folk element. TheBhagawata Mela <strong>of</strong> Melattur and Oothukadand Soolamangalam etc. in the TanjoreDistrict is a high-class classical dancedrama,whereas Bharata Natyam is a solodancewhich IS the ne plus ultra <strong>of</strong> theclassical dance art <strong>of</strong> South <strong>India</strong>.Bhagawata Mela dances present variouspuranic themes through dances by manymen who sing and dance where-as inBharata Natya the artist does not singwhile others sing. The songs in BhagawataMeta are in Telugu as the Naik kings <strong>of</strong>

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKATanjore had it as their court language. Thethemes are the stories <strong>of</strong> Prahlada,Harischandra, Dhruva, Markandeya, Usha,Rukmini, Sita and others. The dancedramascombine fine poetry and elaborateCarnatic music and fine and elaboratedances. The founder <strong>of</strong> this classicaldance-drama was Venkatarama Sastri <strong>of</strong>Melattoor who was a contemporary <strong>of</strong> theimmortal musician Tyagaraja.Influence AbroadFinally I wish to make a passing referenceto the farflung influence <strong>of</strong> <strong>India</strong>n Art inCeylon and Burma and Indonesia and farEast Asia including Thailand (Siam) andCambodia and also in China and Japan. InJava, Bali, Cambodia, and in Eastern Asiagenerally, <strong>India</strong>n art concepts and artmotifshave had a dominant influence. Dr.A. K. Coomaraswami says: “The leadingmotifs <strong>of</strong> Chinese and Japanesebuilding art <strong>of</strong> the pagoda and toru arealso <strong>of</strong> <strong>India</strong>n origin”. (The Arts and Crafts<strong>of</strong> <strong>India</strong> and Ceylon page 117). Mr. Havellsays, “<strong>India</strong>n idealism during the greaterpart <strong>of</strong> this time was the dominant note inthe art <strong>of</strong> Asia whichwas thus brought into Europe; and we finda perfectly oriental atmosphere and strangeechoes <strong>of</strong> eastern symbolism in themedieval cathedrals <strong>of</strong> Europe and see theirstructural growth gradually blossoming withall the exuberance <strong>of</strong> Eastern imagery”. Wefind the influence <strong>of</strong> <strong>India</strong>n art, viz, Hindu24DANCES OF INDIAart and Buddhist art in the temples atAngkor Vat and Prambanan and Borobodurand also particularly in the music and danceand the general cultural atmosphere in theisland <strong>of</strong> Bali. In Indonesia, <strong>India</strong>n art andthe colourful beauty and glory <strong>of</strong> natureand human life and dress and decorationwere blended to perfection. In Bali, thependel, the jangar, the leyong and thekabzyar dances interpret the heroic actions<strong>of</strong> Arjuna and other heroes <strong>of</strong> <strong>India</strong>nmythology. The pendel is a classical danceconnected with temple rituals. The otherdances also interpretPuranic episodes. The Ketjah or monkeydance depicts the Ramayana story. Thereare also dances interpreting the Buddhistand jataka stories. There are also folkdances. The gamelon orchestra, aidedsometimes by vocal music, adds to thefascination <strong>of</strong> the dances. The dancegestures are <strong>of</strong> <strong>India</strong>n origin. The dressand the decoration <strong>of</strong> the Javanese andBalinesedancers are similar to those discernible inthe Ajanta frescoes. Tagore says: “In <strong>India</strong>where exuberance <strong>of</strong> life seeks utterance,it sets them to dance. One who knowstheir peculiar dance- language can followthe story without the help <strong>of</strong> words”.It is thus clear that the art <strong>of</strong> Dance wasborn and grew up in <strong>India</strong> as a spiritual artand spread all over South -East Asia andflourishes even to-day as a supremespiritual art in the house <strong>of</strong> its birth.

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA25DANCES OF INDIAThe Spiritual Background <strong>of</strong> <strong>India</strong>n DanceRUKMINI DEVIOne <strong>of</strong> the greatest and mostancient arts <strong>of</strong> <strong>India</strong> is thedance and as far as I know <strong>India</strong>alone has given it so high a place in bothnational and spiritual life. No one was toolow born for this sacred art, nor anyonetoo great or spiritual for it. From the SublimeBeing comes the inspiration and example.Therefore, everyone who is but part <strong>of</strong> Him,every living creature, is animated by thatspirit <strong>of</strong> creation which is the dance. It isbecause the whole conception <strong>of</strong> art iscosmic and allembracingthat inreality it is undyingand eternal. Itsexpression is many, forit is like the light <strong>of</strong> thesun which sparkles onthe ocean. From theoneness <strong>of</strong> that lifecomes the creativegenius in man. Manintuits the spirit andabsorbshisenvironment. From the harmony <strong>of</strong>theenvironment, the life, the thought, thephilosophy and nature all around, with thecreative spirit within, inspiration is born,and art is the expression.Environment is <strong>of</strong> tremendous importanceto the actual form <strong>of</strong> art. The environmentis what we call national life. If in <strong>India</strong>, thedance, as any other art, is essentiallyspiritual and philosophical, it is merelybecause the sages have given a spiritualmeaning to it. It is also because the verysame sages have, at the same time, helpedto build the nation so that there is n<strong>of</strong>undamental difference between thespiritual and the physical, nor is there adifference between the manifest and theunmanifest. This has been the uniquenessin the civilization <strong>of</strong> <strong>India</strong>. If we understandthe highest, we understand the least als<strong>of</strong>orboth are one.Importance <strong>of</strong> MusicFrom this point <strong>of</strong>view comes thedance tradition <strong>of</strong>our country. Thedance is not an artby itself. It is aunique expression,through the body,synthesising all arts.In reality, though itis the nature <strong>of</strong> thebody to respond torhythm, yet it is thamasic in nature andits inertia expression, which we call dance.Therefore, the perfect harmony <strong>of</strong> thephysical and emotional produces the dance.How is emotion stirred? It is flexible andquickly affected and that which stirs itmost is sound. Sound as movementexpresses itself in music. Music is thespeech <strong>of</strong> the Highest. The firstmanifestation is in terms <strong>of</strong> sound, whichis speech or music. All this is so