Disciplinary Proceeding - finra

Disciplinary Proceeding - finra

Disciplinary Proceeding - finra

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

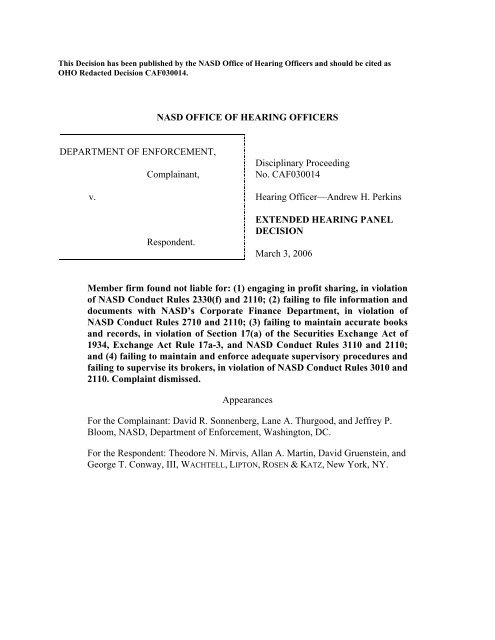

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.NASD OFFICE OF HEARING OFFICERSDEPARTMENT OF ENFORCEMENT,Complainant,v.Respondent.<strong>Disciplinary</strong> <strong>Proceeding</strong>No. CAF030014Hearing Officer—Andrew H. PerkinsEXTENDED HEARING PANELDECISIONMarch 3, 2006Member firm found not liable for: (1) engaging in profit sharing, in violationof NASD Conduct Rules 2330(f) and 2110; (2) failing to file information anddocuments with NASD’s Corporate Finance Department, in violation ofNASD Conduct Rules 2710 and 2110; (3) failing to maintain accurate booksand records, in violation of Section 17(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of1934, Exchange Act Rule 17a-3, and NASD Conduct Rules 3110 and 2110;and (4) failing to maintain and enforce adequate supervisory procedures andfailing to supervise its brokers, in violation of NASD Conduct Rules 3010 and2110. Complaint dismissed.AppearancesFor the Complainant: David R. Sonnenberg, Lane A. Thurgood, and Jeffrey P.Bloom, NASD, Department of Enforcement, Washington, DC.For the Respondent: Theodore N. Mirvis, Allan A. Martin, David Gruenstein, andGeorge T. Conway, III, WACHTELL, LIPTON, ROSEN & KATZ, New York, NY.

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.Table of ContentsI. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 5II. PROCEDURAL HISTORY............................................................................................................ 6III. FACTS ...................................................................................................................................... 8A. Background......................................................................................................................... 81. Industry Commission Rates ............................................................................................ 92. Industry IPO Allocation Practices ................................................................................ 13B. The Firm............................................................................................................................ 19C. The Investigation .............................................................................................................. 21D. Enforcement’s Post-Complaint Development of its Profit-Sharing Theory..................... 28E. The Alleged Profit-Sharing Payments .............................................................................. 301. Non-Economic Cross or Wash Trades.......................................................................... 312. IPO Flips ....................................................................................................................... 33F. No Customer Evidence of Profit Sharing ......................................................................... 351. April 2002 Telephone Interviews ................................................................................. 352. Customer Statements and Memoranda ......................................................................... 363. Customer Affidavits...................................................................................................... 384. Customer Counsel Letters............................................................................................. 385. Hearing Testimony........................................................................................................ 386. On-The-Record Interview Testimony........................................................................... 39G. Statistical Evidence of Profit Sharing............................................................................... 421. Overview....................................................................................................................... 422. Enforcement’s Statistical Evidence—the Ferri-27 ....................................................... 44(a) Frequency of Inflated Rate Commissions............................................................. 44(b) Higher Total Gross Commissions......................................................................... 45(c) Correlation of Total Agency Commissions and Hypothetical Profits .................. 462

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.3. The Firm’s Statistical Evidence.................................................................................... 47(a) Profit Sharers were not Favored ........................................................................... 47(b) No Consistent Ratio of Commissions to Hypothetical Profits ............................. 53(c) Rates above Six Cents per Share were not Uncommon........................................ 564. Enforcement’s Statistical Evidence Lacks Probative Value......................................... 585. Conclusion Regarding Statistical Evidence.................................................................. 64H. The Firm’s IPO Allocation Practices................................................................................ 65I. The Firm’s Supervisory System........................................................................................ 661. The Firm’s Supervisory Structure................................................................................. 672. The Firm’s Supervision of Commissions ..................................................................... 683. The Firm’s Supervision of IPO Allocations ................................................................. 70IV. CONCLUSIONS OF LAW........................................................................................................... 71A. Profit-Sharing Charge ....................................................................................................... 711. Conduct Rule 2330(f) ................................................................................................... 71(a) Sharing Element.................................................................................................... 72(b) Profit Element ....................................................................................................... 752. Post-Conduct Settlements ............................................................................................. 78B. Ethics Charge.................................................................................................................... 791. NASD Conduct Rule 2110............................................................................................ 802. Expert Testimony.......................................................................................................... 82(a) Commercial Bribery Analogy............................................................................... 83(b) Customer–Client Dichotomy ................................................................................ 84C. Corporate Finance Charge ................................................................................................ 881. NASD Conduct Rule 2710............................................................................................ 892. Expert Testimony.......................................................................................................... 91D. Books and Records Charge............................................................................................... 92E. Supervision Charges ......................................................................................................... 941. Conduct Rule 3010 ....................................................................................................... 942. Failure to Supervise Charge.......................................................................................... 963

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.F. Inadequate Supervisory System and Written Procedures Charge .................................... 99V. ORDER ................................................................................................................................. 1004

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.DECISIONI. INTRODUCTIONThe Department of Enforcement (“Enforcement”) brought this proceeding against________________________ (“Respondent” or the “Firm”), an NASD member firm, allegingthat between October 1, 1999, and March 31, 2000, the Firm engaged in profit sharing byaccepting higher-than-normal commission rates from customers seeking allocations of initialpublic offerings (“IPOs”).The Complaint contains six causes of action. The first cause of action, as supplementedby the Bill of Particulars, 1 alleges that the Firm violated NASD’s profit-sharing rule (ConductRule 2330(f)) 2 when, on agency trades of listed securities, and in the absence of any profitsharingagreement or quid pro quo, the Firm accepted customer-set commission rates that werehigher than the normal industry rates paid by institutional customers. Enforcement refers to thesecommissions as “inflated rate commission payments” and alleges that the limited services theFirm provided to its customers did not justify the payments. In addition, although not an elementof the profit-sharing charge, Enforcement alleges that customers made the inflated ratecommission payments in order to gain access to “hot” IPOs. 3In large measure, the remaining five causes of the Complaint spring from the first. Thesecond cause of action alleges that the Firm improperly received inflated rate commission1 Bill of Particulars (Oct. 15, 2003).2 The Complaint further alleges that the Firm thereby violated Conduct Rule 2110, which provides that “[a]member, in the conduct of his business, shall observe high standards of commercial honor and just and equitableprinciples of trade.”3 An IPO is a corporation’s first offering of stock to the public. A hot IPO or hot issue is one in which the stockimmediately trades at a premium in the aftermarket because there is greater public demand for the stock than thereare available shares.5

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.payments and permitted its customers to try and influence the Firm to allocate them IPO shares,in violation of NASD Conduct Rule 2110. The third cause of action alleges that the Firmviolated NASD’s corporate finance rules, NASD Conduct Rules 2710(b)(1) and 2710(5)(a)(ii),and NASD Conduct Rule 2110, by failing to file information with NASD that disclosed theFirm’s profit sharing in its customers’ accounts. The fourth cause of action alleges that the Firmfailed to maintain accurate books and records that reflected the shared customers’ profits, inviolation of NASD Conduct Rules 3110 and 2110, Section 17(a) of the Securities Exchange Actof 1934 (“Exchange Act”), and Exchange Act Rule 17a-3. The fifth cause of action alleges thatthe Firm failed to supervise its registered representatives, in violation of NASD Conduct Rules3010(a) and 2110. The Complaint charges that the Firm’s supervisors failed to follow up onnumerous “red flags” of improper profit sharing. The final cause of action alleges that the Firmfailed to establish, maintain, and enforce an adequate supervisory system and written supervisoryprocedures that were reasonably designed to achieve compliance with applicable federalsecurities laws and NASD rules. Specifically, the Complaint charges that the Firm’s supervisoryprocedures provided insufficient standards regarding allocation of IPO shares, the receipt ofcommissions, and the supervision of Firm employees who allocated IPO shares, and the Firmthereby violated NASD Conduct Rules 3010(a), 3010(b), and 2110.II.PROCEDURAL HISTORYThe Department filed the Complaint on April 15, 2003. The Firm filed its Answer onMay 23, 2003, and denied any wrongdoing. In addition, the Firm raised 12 affirmative defenses.On September 16, 2003, the Firm filed a Motion for Summary Disposition, whichEnforcement opposed on October 24, 2003. The Firm’s motion sought dismissal of theComplaint on two of its affirmative defenses. First, the Firm argued that Enforcement’s profit-6

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.sharing theory is invalid because it amounts to a rule change that NASD did not submit to theSecurities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”), as required by Section 19(b) of the ExchangeAct. Second, the Firm argued that the Complaint must be dismissed because Enforcement hadconducted its investigation in a manner that violated basic tenets of investigative fairness andNASD’s obligation under Section 15A of the Exchange Act to provide a fair procedure fordisciplining members. The full Extended Hearing Panel (“Panel”) heard oral argument on theFirm’s motion on January 14, 2004, in Washington, DC. The Panel denied the motion by Orderdated March 18, 2004. 4Between January 19, 2005, and February 24, 2005, a 17-day hearing was held in NewYork City. 5 The Panel included the Hearing Officer, a former member of NASD’s Board ofGovernors, and a former member of NASD’s District 10 Committee. Enforcement presented 12witnesses and introduced 37 exhibits. The Firm presented 14 witnesses and introduced 172exhibits. In addition, the Parties introduced 15 joint exhibits. 6 The transcript of the hearingcontains more than 4,600 pages.Both Parties relied heavily on expert opinion testimony. In total, the Panel heard from 17experts. The Panel considered all of the opinion evidence, which diverged significantly oncrucial points. However, the Panel did not accept the experts’ opinions where they strayed into4 In light of the Panel’s findings in this Decision, the Panel did not address the Firm’s remaining affirmativedefenses.5 The hearing was postponed twice. The original hearing was scheduled for February 2004; however, the Partiesrequested that it be postponed to give the Panel ample time to consider the Firm’s Motion for Summary Disposition.The Hearing Officer rescheduled the hearing to November 2004. Enforcement later moved to adjourn the hearingagain because two members of its defense team were scheduled to participate in another hearing that conflicted withthe schedule in this case. Accordingly, the Hearing Officer rescheduled the hearing with the Parties’ agreement toJanuary 19, 2005.6 The hearing transcript is cited as “Tr.,” followed by the page number, the line number, and the witness’s name.Enforcement’s exhibits are referred to as “CX,” Respondent’s are referred to as “RX,” and the joint exhibits arereferred to as “JX.”7

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.those areas reserved exclusively for the Panel’s determination. For example, several expertstestified directly or tangentially on conclusions of law. The Panel did not give weight to suchtestimony in reaching its decision. 7Following the hearing, the Parties submitted post-hearing briefs. Enforcement filed itsbrief on May 16, 2005, and the Firm filed its brief on June 27, 2005. The Panel then heardclosing arguments in Washington, DC, on July 27, 2005.In summary, the Panel concluded that Enforcement failed to prove that the Firm shared inthe profits of its customers’ accounts or engaged in other conduct that contravened highstandards of commercial honor or just and equitable principles of trade. Accordingly, the Paneldismissed the primary charges in the Complaint. In addition, the Panel dismissed the remainingcharges. To the extent that the remaining charges were not dependent on a finding that the Firmhad engaged in profit sharing in violation of Conduct Rule 2330(f), the Panel concluded thatEnforcement had not proven them by a preponderance of the evidence.III.FACTSA. BackgroundA considerable amount of testimony centered on two issues: (1) the customary level ofcommission rates institutional customers paid on agency trades of listed securities; and (2) the7 See, e.g., Snap-Drape, Inc. v. Commissioner, 98 F.3d 194, 198 (5th Cir. 1996) (Tax Court properly declined toadmit expert witness reports offered by taxpayer that “improperly contain[ed] legal conclusions and statements ofmere advocacy”); United States v. Scop, 846 F.2d 135, 138–40 (2d Cir. 1988), modified, 856 F.2d 5 (2d Cir. 1988)(“repeated statements [by expert] embodying legal conclusions exceeded the permissible scope of opiniontestimony”); In the Matter of Potts, 53 S.E.C. 187, 1997 SEC LEXIS 2005, at *45 (1997) (ALJ properly excludedtestimony of law professor and former SEC commissioner that would have consisted of “mere opinion of law” and“would not [have] provide[d] evidence”); Department of Enforcement v. Fiero, No. CAF980002, 2002 NASDDiscip. LEXIS 16, at *91 (N.A.C. Oct. 28, 2002) (“the lawyers for the parties, not expert witnesses, ha[ve] the taskof arguing to the Hearing Panel what the applicable legal standards [are]”).8

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.methods used by brokers to allocate IPO shares to their customers. In each case, Enforcementargued that the Firm’s practices materially deviated from accepted industry norms and violatedapplicable NASD conduct rules. Accordingly, the Panel first considered these underlying issues.1. Industry Commission RatesFixed commissions were eliminated in 1975. 8 Since then, institutional customersgenerally have set the rates they pay, which was true during the relevant period. 9The Parties agreed that commission rates paid by the largest institutional customers foragency trades of listed securities generally fell within the four to seven cents per share levelduring the relevant period, depending on the nature of the transaction and services rendered.Three of Enforcement’s experts addressed this issue. Enforcement’s key expert on commissionrates, J. Patrick Campbell (“Campbell”), 10 stated in his report that the typical rate wasapproximately six cents per share for both large and small institutional accounts. 11 Dennis A.Green (“Green”) 12 stated that the generally accepted institutional rate at the time was between8 JX 14 49 (Joint Stipulations).9 Id. 38.10 Campbell has a wealth of expertise regarding the securities industry and financial market structure, which heobtained from his more than 30 years experience in the industry. Campbell spent the first 26 years of his career withThe Ohio Company, a privately held investment-banking firm. Campbell sat on The Ohio Company’s Board ofDirectors from 1991 until 1996, during which time he oversaw most of the company’s institutional and retailtrading. At the time of the hearing, Campbell was acting Chief Operating Officer of the American Stock Exchange.He served in numerous industry roles with, among others, the Securities Industry Association and NASDAQ. Inaddition, Campbell held a number of leadership positions at NASDAQ, including Chief Operating Officer and a asmember of its Board of Directors. He retired from NASDAQ at the end of 2001 as the President of NASDAQ USMarkets. CX 32 (Campbell report).11 CX 32 at 6 (Campbell report).12 Dennis A. Green is a securities industry consultant. He worked as a trader and supervisor at NASD member firmsfor more than 38 years. In May 2002, he retired from Legg Mason where he held the position of Senior Vice-President, Manager of NASDAQ Equity Trading. CX 34 at 1-2 (Green report).9

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.five and seven cents per share, regardless of the size of the trade. 13 And Edward A. Raha(“Raha”) 14 stated that five to six cents per share was a “fair rate” at the time. 15Based on the foregoing, Enforcement argued that the prevailing fair rate during therelevant period was six cents per share for all institutional agency trades, irrespective of eitherthe customer’s or the trade’s size. Thus, Enforcement questioned any rate that exceeded six centsper share.The Panel found, however, that industry rates were far from uniform. In fact,Enforcement’s experts recognized that some customers paid less than three cents per share andothers paid substantially more than six cents per share. For example, Raha testified that rates aslow as two cents per share were common for simple executions. 16 And, at the high end,Enforcement acknowledged that other member firms received commission rates equivalent to therates at issue here: over 20 cents per share. 17The Firm’s experts testified that commission rates, particularly for smaller customers,were far from uniform and that many major broker-dealers accepted commissions far in excessof six cents per share. For example, the Firm presented evidence that Morgan Stanley DeanWitter (“Morgan Stanley”) maintained a commission formula that yielded rates as high as 7113 CX 34 at 4 (Green report).14 Edward A. Raha holds a Masters of Business Administration in finance from the University of Chicago GraduateSchool of Business. Raha has been employed as a broker and trader in the securities industry since 1983. Between1990 and 1994, he worked at Bankers Trust, managing the bank’s private equity portfolio, and at Donaldson, Lufkinand Jenrette, as a broker for high net worth individuals and large institutions. Currently, Raha is employed byManaged Quantitative Advisors, a registered investment advisor/hedge fund. CX 36 at 2-4 (Raha report).15 CX 36 at 3 (Raha report).16 Tr. 2109:15-18 (Raha).17 JX 14 39 (Joint Stipulations).10

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.cents per share on trades of 10,000 shares at $100 per share. 18 Enforcement did not present anyevidence disputing these facts. To the contrary, Raha, one of Enforcement’s commission experts,testified that his former firm, Donaldson, Lufkin and Jenrette, maintained a rate card 19 thatreflected rates as high as 27, 35, 42, and 49 cents per share for 10,000-share trades at share pricesof $25, $50, $75, and $100 respectively per share. 20 Green, another Enforcement expert, similarlyadmitted that many firms maintained rate schedules that permitted brokers to acceptcommissions at rates exceeding 20 cents per share. 21 Indeed, Green testified that his former firm,Legg Mason, maintained rate schedules with rates “way more than six cents per share.” 22Nevertheless, Enforcement argued that Green and Raha supported its position that ratesin excess of six or seven cents per share were excessive for institutional customers. The Panel,however, rejected their opinions because they based their conclusions on non-comparable data.Green and Raha referenced data concerning institutions many times the size of the customerswho paid the “inflated rate commissions” to the Firm. 23 Green based his opinion on his personalexperience with customers at Legg Mason that had assets in excess of $10 million, while manyof the Firm’s customers were much smaller. 24 Moreover, Green did not conduct a survey ofcommission rates to verify his conclusions. 25 Raha on the other hand testified about the rates paid18 RX 234; RX 238.19 RX 230.20 See RX 239 at 10534 (calculations based on RX 230).21 Tr. 1182:24-1183:13 (Green).22 Tr. 1185:12-14 (Green).23 Green formulated his opinion without any information about the size of the Firm’s customers. Tr. 1131:4-9,1193:18–24 (Green).24 Tr. 1162:8-12, 1163:2-8 (Green).25 Tr. 1185:17-1186:14 (Green).11

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.by investment advisors, although none of the Firm’s customers were investment advisors, 26 andhis knowledge of commission rates was based on his experience as someone who managedapproximately $100 million in client assets, and traded approximately 200 million sharesannually. 27 Significantly, 200 million shares annually is approximately five times the totalnumber of shares traded by all 35 customers at issue in this case during the relevant period. 28Finally, both Green and Raha relied on industry data derived from surveys of institutionalcustomers far larger than any of the Firm’s. For example, Green relied on a New York Timesarticle 29 that cited to a report prepared by the Plexus Group, a company that studies commissionsfor buy-side firms . 30 However, Green was not aware that the Plexus report was based on tradedata from 125 clients that managed $4.5 trillion in equities, which meant that the average clientmanaged $36 billion in assets and traded hundreds of millions of shares per quarter. 31 Raha reliedon Plexus data as well as data from another firm called Abel/Noser, which similarly was basedon firms that traded billions of dollars annually. 32 The Firm’s customers were dwarfed incomparison. For example, 20 of the customers who paid inflated rate commissions had a netequity of less than $5 million each. 33 Enforcement’s experts did not study separately the practicesof such smaller firms to confirm their general conclusions regarding “institutional rates.”26 Tr. 2163:15-21 (Raha was asked to render opinion “on the commissions and commission rates small to mediumsizedinvestment advisor[s] would be expected to pay”).27 Tr. 2122:5-7, 2125:17-25, 2126:12-14 (Raha).28 See RX 312; Tr. 2127:14-20 (Raha).29 See Tr. 1187:7–1188:7, 1188:24–1189:5; CX 34 at 5 (Green report).30 Tr. 1187:15-20, 1190:21–1191:8 (Green).31 Tr. 1192:3-1193:17, 1194:13-1195:18 (Green).32 Tr. 2169:14-16, 2169:25–2170:9, 2170:15-2171:2, 2171:12–2173:2 (Raha); CX 36 at 18, 22 (Raha report).33 RX 247 at 10636-37.12

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.The Panel concluded that while six cents per share was a very common rate paid by largeinstitutions, it was not the universal standard for smaller “institutional” customers. Indeed, theevidence shows that larger institutions with greater volume to give brokers often paid less thansix cents per share, while smaller institutional customers paid substantially higher rates in orderto obtain services and maintain a favorable relationship with their brokers. Moreover, memberfirms did not prohibit the acceptance of commission rates above 20 cents per share where thecustomer set the rate without being pressured to do so by its broker. Accordingly, the Panel didnot consider the magnitude of the commission rates by itself to evidence profit sharing or otherwrongful conduct.2. Industry IPO Allocation PracticesThe industry-wide practice is to allocate IPO shares to broker-dealers’ best customersmeasured by their aggregate commissions. This method has been accepted industry practice forat least the last 30 years. 34 All of the experts who testified on this point agreed. For example,Edwin R. Olsen, 35 who was involved in more than 1,000 underwritings during his career,testified on behalf of the Firm that he knew of no other way to allocate IPO shares. 36 Indeed,Olsen explained that the firms for which he worked gave very specific instructions on how toallocate IPOs based on commission business. They directed him to ensure that he allocated thefirms’ resources “to the firm’s largest accounts as measured by gross aggregate commissions orthe revenue and the value … those institutions brought to the firms .…” 37 The Firm’s experts34 Tr. 3159:11–3160:13 (Olsen).35 Edwin R. Olsen has more than 30 years experience in the securities industry, 25 of which involved responsibilityfor managing the allocation of shares in IPO and secondary offerings. Most recently, Olsen was employed by J.P.Morgan Chase as Managing Director of Equity Capital Markets. Olsen retired from J.P. Morgan Chase in February2002. RX 8 at 1003-1005 (Olsen report).36 Tr. 3163:9-13 (Olsen).37 Tr. 3152:3-13 (Olsen).13

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.Dan W. Lufkin (“Lufkin”) 38 and Professor John C. Coffee, Jr. (“Coffee”) 39 agreed. Lufkintestified that it was “the common practice of firms to allocate shares to best or good customersbased on their commission business.” 40 According to Coffee, “the basic rule was—within thisindustry—that aggregate commissions were going to be the principal criterion upon which IPOshares were allocated when there was an oversubscribed or hot IPO.” 41 In addition, StanleyShopkorn (“Shopkorn”), 42 another Firm expert, testified to this practice. 43 Indeed, Enforcementstipulated that it was a common practice during the review period for firms to take commissionbusiness into account in making IPO allocations. 44Enforcement further stipulated that an underwriter lawfully may exercise discretion inIPO allocations, and may allocate IPO shares to customers as it chooses, unless such an38 Dan W. Lufkin is the founder and former Chairman of Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette, Inc. He is a graduate ofHarvard Business School, and he served as a Governor of the NYSE. RX 6 at 848, 851 (Lufkin report).39 Professor John C. Coffee, Jr., holds a law degree from Yale University and is the Adolf A. Berle Professor ofLaw at Columbia University Law School, specializing in corporate and securities law. Coffee has served on theLegal Advisory Board of NASD and on the Legal Advisory Committee to the Board of the NYSE. RX 2 at 78-79(Coffee report).40 Tr. 3657:9-13; accord RX 6 at 851-52 (Lufkin report).41 Tr. 4287:2-6; RX 2 at 92, 106 (Coffee report) (citing, in part, remarks of former SEC Chairman Arthur Levittsupporting the practice of allocating hot IPOs to brokers’ best customers as measured by their aggregate level ofcommission business and acknowledging that shares are often allocated according to business relationships andother subjective criteria) (citations omitted).42 Stanley Shopkorn runs Shopkorn Management LLC, an investment firm with seven securities professionals.Shopkorn has over 35 years of experience as a securities industry professional. From 1973 to 1991, he was withSalomon Brothers. In 1978, he became a general partner of Salomon Brothers and eventually served as its ViceChairman and as a member of its Executive Committee. Following his tenure at Salomon Brothers, Shopkorn wasthe Chairman of Ethos Capital, a hedge fund that merged into Moore Capital in 1996. He then managed all ofMoore Capital’s equity activities, including the purchase of underwritings. RX 10 at 1958-59 (Shopkorn report).43 Tr. 3357:25–3358:8 (Shopkorn); accord RX 10 at 1954 (Shopkorn report).44 JX 14 37 (Joint Stipulations).14

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.allocation constitutes spinning, 45 an unlawful quid pro quo, or other prohibited conduct. 46 Suchlawful discretion includes allocating IPO shares to an underwriter’s best customers measured byaggregate commission business the customers did with the underwriter.The Panel further found that customers that desire IPO allocations have to compete forthem by the amount of non-IPO commission revenue they generate. 47 This is standard practicethroughout the securities industry. 48 For customers who are unable to do a substantial volume oftrades, this means they must find an alternate way to generate sufficient non-IPO commissionbusiness, or they are ineligible to receive IPO allocations. 49Several Firm customers confirmed this industry-wide practice. For example, TR, anindividual who managed about $1 million of “family money,” 50 testified at his on-the-recordinterview that he learned when he first entered the business that he had to establish himself as a“good client” to get IPO allocations and that broker-dealers determined their good clients by theamount of commission business they did. 51 He understood “good clients” to be regular traders45 Spinning is the practice whereby underwriters allocate hot IPO shares to executives of prospective investmentbanking clients in return for future investment banking business.46 JX 14 36 (Joint Stipulations).47 See, e.g., Tr. 376:15-24 (Ozag).48 See, e.g., Tr. 1754:18-20, 1694:22-25 (Campbell); Tr. 2161:22-2162:2 (Raha) (it was “standard practice to look ataggregate commissions and potential for aggregate commissions in allocating IPOs”); Tr. 2493:11-13; accord Tr.2448:8-11 (Bogle) (acknowledging “common practice in the industry to take commission business into account ingiving out IPOs”).49 See, e.g., RX 1 at 23 (Antolini report) (professional investors pay commissions “to maximize their aggregateamount of commission business in order to be considered one of an underwriter’s ‘best’ customers” so that they canreceive IPO allocations). Robert Antolini, one of the Firm’s experts, is one of the principals of Great South BayTrading LLC, a small-cap hedge fund. Before establishing Great South Bay in 1998, Antolini spent his nearly 40year career at several NASD member firms where he held various senior positions relating to the firms’ over-thecounteroperations. His experience involved his firms’ IPO allocation practices. RX 1 (Antolini report).50 Despite the relative small size of this account, the Firm treated it as an “institutional account.”51 RX 121 at 6440-41, 6495-97. Some large firms even had express policies that required at least 50% of theircustomers’ business come from non-syndicate trades. The Firm did not have such a policy.15

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.who generated commissions. 52 Thus, to be seen as a “good client,” TR concluded he had to tradefrequently and pay higher commission rates than would be necessary if he only wanted tradeexecutions. 53TR described his process of selecting a registered representative and becoming a goodclient as follows. First, TR identified firms and registered representatives at those firms whichhad access to IPOs. He would do this by observing the firms listed on the prospectuses hereceived and by reviewing IPO tombstone announcements carried in the Wall Street Journal andother financial publications. 54 Once he identified a broker-dealer that had access to IPOs, hecalled the firm to open an account. 55 TR testified that to his best recollection he made such a callto establish his account at the Firm. 56After TR identified a firm and broker, he would open an account and commence doing alimited amount of business with the broker to evaluate whether the broker was one of the betterproducers of IPO shares at the firm. 57 TR referred to this as a “feeling out period,” during whichhe would do a minimal amount of business with the new broker. If TR was pleased with theallocations he received, he increased the amount of business he did with the broker. 58If a broker proved he had good access to IPOs, TR’s next step was to attempt to increasethe size of his allocations. TR did so by doing more volume and by increasing the cents-per-52 RX 121 at 6446.53 Id.54 RX 121 at 6442.55 Id.56 Id.57 RX 121 at 6495-96.58 RX 121 at 6496.16

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.share rates he paid. The object was to become a better client. TR viewed this process as acompetition with the brokers’ other customers who also were interested in purchasing IPOshares. 59 The process proved difficult because it operated as a “blind draw.” TR did not learnwhere he stood until the morning an IPO came out. 60 Only then would he know how he stoodwith the broker. If TR got a good allocation, he knew that the level of business he was doingwith that broker was sufficient. If not, he knew he had to increase the level of commissionrevenue he did with the broker. 61TR’s sole reason to increase business with the Firm and other similar firms was toreceive greater IPO allocations. TR did not base the rate he paid on his profits. 62 Nor did he setcommissions as a percentage of his IPO profits. 63 TR pegged both his trading volume and hiscommission rates to the levels he considered necessary to obtain IPO allocations. He judgedthose levels through a trial and error process; he never discussed with any broker the amount heneeded to pay in order to become a “good client.” 64TR further explained that his limited capital meant that he had to engage in short-termtrading because he did not have enough capital to become a “good client” and hold investmentsfor the long term. Instead, TR relied on frequent trading to generate a valued level of business.59 RX 121 at 6449.60 Id.61 RX 121 at 6448.62 RX 121 at 6492-93.63 RX 121 at 6493.64 RX 121 at 6462.17

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.Nonetheless, TR testified that he did not engage in trades only to benefit his broker. 65 To thecontrary, TR testified that he expected to make a profit on all of his trades. 66TR’s experience typifies that of other small “institutional” customers. In contrast, largeinstitutions use their superior economic advantage to obtain IPO allocations. For example,Fidelity Investments insists upon receiving at least twice the next-highest allocation in return forlarge order flow. 67 This policy is referred to in the industry as the “Fidelity Formula.” If a brokerdealerrefuses to comply, Fidelity puts it in the “penalty box” by pulling business from therecalcitrant firm. 68Enforcement’s experts testified that industry participants and regulators accepted thepractice of favoring such large institutions. For example, Campbell testified that he saw nothingwrong with a customer directing commission business to a broker-dealer to improve its standingas a good customer. 69 Even John C. Bogle, 70 Enforcement’s ethics expert, could only quibblewith the ethics of the Fidelity Formula before ultimately conceding that it was an acceptedpractice to favor those customers who directed commission business to a broker-dealer for thepurpose of influencing the IPO allocation process.65 RX 121 at 6458-59.66 Id.67 See, e.g., Tr. 2494:10-15.68 Tr. 3185:18–3188:15 (Olsen); 2494:20–2495:7 (Bogle).69 Tr. 1703:13–1704:7 (Campbell).70 John C. Bogle, founder of The Vanguard Group, has a long and distinguished career in the financial servicesindustry. He started his career in the field of financial markets in 1951 following his graduation from PrincetonUniversity, magna cum laude, with a degree in economics. He served for 30 years as Chief Executive Officer of twomutual fund firms—Wellington Management Company from 1967 until 1974, and The Vanguard Group from 1974until 1996. Among his numerous accomplishments, he has written four books and many articles about investing,financial markets, and mutual funds. CX 31 (Bogle report).18

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.Enforcement’s witnesses expressed no concern over the fact that the largest institutions,such as Vanguard and Fidelity, often pay higher cents-per-share commission rates to brokerdealersfrom which they sought new issues. Every witness who addressed the topic readilyadmitted that large institutions could pay far less than six cents per share on trades of listedsecurities. Indeed, the largest customers have the economic power to push the rate below a pennya share. Nevertheless, they pay more where they seek other services, including IPO allocations.In so doing, the large institutions routinely reward broker-dealers with increased order flow andcommissions for generous IPO allocations.In conclusion, the Panel finds that there was keen competition for IPOs during the reviewperiod, which drove institutional customers to direct order flow—and pay increased commissionrates—to those broker-dealers that had a supply of IPOs. In both cases, customers voluntarily sethigher commission rates to increase their relative position as “good customers.” But in neitherscenario did this conduct alone amount to profit sharing.B. The FirmThe Firm is a small registered broker-dealer in New York City. 71 At no time has it hadmore than about 12 registered employees. 72 During the relevant period, the Firm had no morethan 100 active accounts at any one time (i.e., accounts that executed at least three trades permonth) and processed only about 40 to 50 agency trades per day. 73 Most of the Firm’s customerswere hedge funds and other institutional investors. 7471 JX 14 1, 3 (Joint Stipulations).72 JX 14 4 (Joint Stipulations).73 Tr. 1265–68, 1271 (LS).74 JX 14 5 (Joint Stipulations).19

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.KL founded the Firm in 1974, and he has headed the Firm since then. 75 During the sixmonthperiod in issue, October 1, 1999, to March 31, 2000, KL was the Firm’s Chief ExecutiveOfficer; CK was the Chief Operating Officer; JB was the Chief Compliance Officer and ChiefFinancial Officer; and LS was the head trader and sales supervisor. 76Commission business was a minor portion of the Firm’s revenue. The Firm earned mostof its revenue from its investments. 77 During the relevant period, the Firm derived 11.8% of itsgross revenue from commissions. 78 The Firm did not stress commission business, and most of itsorder flow was unsolicited. 79 JB testified that commission business was relatively unimportant toKL, who, JB believed, looked to commission revenue merely to cover the Firm’s overhead. 80The Firm actively participated in new offerings. Thanks to a close relationship withCredit Suisse First Boston (“CSFB”) forged in the 1980s, the Firm often was brought into thesyndicate or selling group in offerings lead-managed or co-lead-managed by CSFB. 81 Most of the57 IPOs in which the Firm participated during the relevant period were such offerings. 82 TheFirm’s allocations ranged from a low of 400 shares to a high of 300,000 shares. 83 In one-third ofthese IPOs, the Firm received 10,000 shares or fewer. 84 In a given IPO, the Firm’s four sales75 JX 14 4 (Joint Stipulations); Ans. 1.76 JX 14 4 (Joint Stipulations); Tr. 1241, 1244, 1452, 1569.77 Tr. 1566–67.78 RX 350.79 Tr. 1570:2-3 (JB).80 Tr. 1568:11-14 (JB).81 See Compl. 12.82 JX 14 7–8, 54–55 (Joint Stipulations).83 See CX 7 (All Review Period IPOs).84 Id.; see also Tr. 620 (Ozag).20

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.representatives got 30 to 35% of the Firm’s retention for allocation to customers. The rest of theretention was distributed among the Firm’s house accounts—accounts to which no broker wasassigned and to which IPO allocations were made by a supervisory principal. 85 The Firm’s IPOallocations were based upon, among other things, the aggregate amount of business the customerhad generated in the past, the customer’s potential to develop regular commission business, andthe customer’s expressed interest in becoming a holder of the shares. 86C. The InvestigationEnforcement opened the investigation that led to the filing of the Complaint in thisproceeding because it had been investigating CSFB’s IPO allocation practices. 87 The CSFBinvestigation originated out of a broader inquiry by NASD and the SEC into whether brokerdealershad taken advantage of customers during the “hot” IPO boom of the 1999–2000 period.Ultimately, the CSFB investigation focused on evidence that, in exchange for shares in hot IPOs,CSFB had wrongfully extracted from certain customers a percentage of the profits thosecustomers made by flipping 88 their IPO stock. The SEC alleged that CSFB forced customers tocomply by withholding IPO allocations from those customers who refused to make thedemanded payments. The SEC and NASD contended that CSFB’s extraction of payments fromits customers amounted to impermissible profit sharing, in violation of NASD Conduct Rule85 JX 14 59, 77 (Joint Stipulations); Ans. 18.86 JX 14 56 (Joint Stipulations).87 Tr. 174. These investigations were launched because of an anonymous tip letter received by NASD’s CorporateFinancing Department. Tr. at 2839:19-22 (Price).88 Flipping is the process of buying shares in an IPO and selling them immediately for a profit. A customer whoengages in this practice is called a flipper.21

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.2330. 89 Here, however, there is no allegation that the Firm or any of its brokers coerced anycustomer to pay commissions to the Firm in connection with IPO allocations.In order to analyze CSFB’s allocation practices, Joseph Ozag (“Ozag”), NASD’s leadinvestigator on both the CSFB and the Firm investigations, formulated a criterion to define thescope of the CSFB investigation. 90 Ozag determined that he would limit his inquiry totransactions of 20 cents per share or more on trades of 10,000 shares or more.Ozag developed the 20-cent, 10,000-share metric in two steps. First, at the start of theCSFB investigation, Ozag and other NASD staff determined that they wanted to examine“institutional” size trades. Ozag understood that trades of 10,000 shares had to be reported as ablock trade, so he defined “institutional trades” as trades of 10,000 shares or more. 91Enforcement adopted Ozag’s definition as the CSFB investigation progressed, and Enforcementused the same definition in this case. 92Ozag developed the second criterion based on his discussions with the head of EquitySales Trading at CSFB. 93 During the on-site investigation at CSFB, Ozag interviewed a numberof employees selected by CSFB to better understand the nature of CSFB’s business andoperations. One of those employees was Tony Ehinger (“Ehinger”), the head of CSFB’s EquitySales Trading. Ozag asked Ehinger if there was a standard or normal commission in the industryfor 10,000-share trades done on an agency basis in listed securities. Ehinger replied that he could89 CX 50. The SEC alleged that the cooperating customers channeled payments to CSFB in the form of excessivebrokerage commissions generated in unrelated securities trades that the customers effected solely to share their IPOprofits with CSFB. In January 2002, CSFB settled all charges related to its IPO allocation practices.90 Tr. at 320:10-17 (Ozag).91 Tr. 313:10-15 (Ozag).92 Tr. 313:10-15 (Ozag).93 Tr. 326:5-25 (Ozag).22

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.not say that there was a standard commission, but commissions on such trades ranged from 6 to10 cents per share, with 6 cents being more the norm in the relevant period. 94 Ozag then doubledthe top end of the range and arrived at 20 cents per share—a value he considered well outside thenorm. In his opinion, such a commission would be “unusual or semi-unique.” 95When Ozag opened the [] investigation [of the Firm], he applied the same metric he haddeveloped for the CSFB investigation to define unusual, institutional-size trades. However,whereas Enforcement used the metric as a data management tool in the CSFB case, here,Enforcement used the metric to define profit sharing under Conduct Rule 2330(f).Ozag opened the [] investigation [of the Firm] because he noticed during the CSFBinvestigation that the Firm’s name often appeared as a member of either the syndicate or sellinggroup. 96 Ozag suspected that the Firm might have engaged in conduct similar to that charged inthe CSFB case. 97 Ozag limited his investigation to the Firm’s agency trades executed betweenOctober 1, 1999, and March 31, 2000, because this was a period of many hot IPOs. 98To test his suspicion that the Firm had accepted profit-sharing payments in the form ofhigher-than-normal commissions on agency trades, Ozag asked the Firm to provide trade data forall agency transactions of 10,000 shares or more where the commission equaled or exceeded 20cents per share. 99 In addition, on May 21, 2001, Ozag delivered a Rule 8210 request that the Firmprovide a broad range of documents relating to all equity IPOs the Firm participated in during94 Tr. 326:13-16 (Ozag).95 Tr. 326:21-25 (Ozag).96 Tr. 174:22-24, 187:7-10 (Ozag). CSFB led or co-led 85% of the IPOs Ozag reviewed. Tr. 188:2-3 (Ozag).97 See Tr. 183:2-5 (Ozag).98 Tr. 182:16–183:18. The Firm participated in more than 50 IPOs during the review period. JX 14 54 (JointStipulations).99 Tr. 183:6-10. Exhibit CX 9 lists the agency trades by customer.23

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.the review period and its IPO allocation policies and procedures. 100 The Firm produceddocuments responsive to Ozag’s Rule 8210 request during the on-site visit. 101 The Firm alsoproduced documents in response to supplemental Rule 8210 requests Enforcement made after itson-site visit. 102Ozag then “eyeballed” the data the Firm produced and concluded that it looked like manytrades with inflated rate commission payments had been executed on or about the days on whichthe Firm had participated in a hot IPO. 103 With his suspicion tentatively confirmed, Ozagproceeded to load the data he had collected into a computer program he developed for the CSFBinvestigation, which he called a Matched Transaction Analysis. 104The Matched Transaction Analysis was a computer query with two tables. The first heldthe agency trade data, and the second held the data related to the Firm’s IPO allocations. Theprogram compared the agency transactions completed on or within one business day of an IPOwith the Firm’s IPO allocations. 105 The purpose was to identify customers who paid inflated ratecommission payments of 20 cents or more on trades of 10,000 shares or more who also receivedIPO shares from the Firm. 106 From this analysis, Ozag found that all customers who paid aninflated rate commission received at least one hot IPO during the review period. 107 AlthoughOzag found no apparent difference in the allocations to customers who had not made inflated100 RX 102; JX 14 86 (Joint Stipulations).101 JX 14 87 (Joint Stipulations).102 Id. 88.103 Tr. 188:8-12 (Ozag). Exhibit CX 7 lists the IPOs the Firm sold during the review period.104 Tr. 188:12-16 (Ozag).105 Tr. 188:12–189:4, 199:16-20 (Ozag).106 Tr. 188:15–189:4 (Ozag).107 Tr. 191:20-22 (Ozag).24

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.rate commission payments within one day of an IPO, Enforcement concluded that the MatchedTransaction Analysis confirmed its tentative thesis that the Firm’s customers had made profitsharing payments to the Firm. 108Next, Enforcement took on-the-record testimony from 11 Firm employees—fourmanagers, four sales representatives, and three individuals on the Firm’s trading desk. 109 Inaddition, Enforcement informally interviewed three of the Firm’s customers regarding theircommission payments. 110 Enforcement had wanted to interview others, but many refused tocooperate. 111On April 9, 2002, Enforcement delivered a Wells notice to the Firm telephonically. 112 TheFirm submitted its initial Wells Submission on May 31, 2002, 113 and, on September 23, 2002,met with Enforcement to discuss the investigation. 114 Thereafter, between October 2002 andFebruary 2003, Enforcement interviewed an additional customer on an unsworn basis and tookthe on-the-record testimony of four other customers. 115 Each customer denied that he had enteredinto an agreement to share profits with the Firm or any of its registered representatives. 116108 See Tr. 455:3-7 (Ozag). Enforcement never analyzed whether there was a difference in the quantity of shares theFirm allocated customers depending on whether they made inflated rate commission payments.109 JX 14 90 (Joint Stipulations).110 See RX 106 (Enforcement’s interview notes).111 RX 111.112 JX 14 91 (Joint Stipulations).113 RX 107.114 JX 14 92 (Joint Stipulations).115 JX 14 94, 96 (Joint Stipulations). The Firm provided Enforcement with contact information for each of the 30customers Enforcement wanted to interview. RX 112; RX 113. In addition, the Firm encouraged its customers tocooperate with NASD’s investigation although Enforcement never requested the Firm’s assistance. Tr. 565:17-24(Ozag).116 Tr. 344:23–346:14; 350:5-18; 355:13–357:11; 368:25–369:3; 371:18-25; 547:7-17 (Ozag); RX 106 at 6199,6201, 6203, 6215, 6231–6233, and 6235; CX 38 at 68-69; RX 130 at 6754-55.25

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.Ultimately, Enforcement reached the following conclusions regarding commissionpayments at the Firm, which are incorporated into the Joint Stipulations (JX 14) filed in thiscase:• “[The Firm]’s customers decided themselves what commission rate theywould pay.” (Joint Stipulation No. 41.)• The Firm never “urged or demanded that its customers pay a set amount orrange of commissions or pay commissions at ‘inflated’ rates.” (JointStipulation No. 42.)• The Firm never “told the customers at issue that they had to pay a setamount or range of commissions or pay commission at or above any centsper-sharerate in order to receive IPO allocations.” (Joint Stipulation No.43.)• “None of the customers inquired of [the Firm] what level of commissions(gross or cents-per-share) they would have to pay in order to receive IPOallocations.” (Joint Stipulation No. 44.)• “[The Firm]’s historical practices and procedures with regard to customercommissions and IPO (and secondary) allocations during the time periodcovered by the Complaint were the same as those in existence at the Firmsince the elimination of fixed commissions in 1975.” (Joint StipulationNo. 49.)These findings distinguish this case from the CSFB matter.26

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.In addition, Enforcement concluded that order flow from the customers Enforcementalleged made inflated rate commission payments was unsolicited, and was given directly to thetrading desk. 117 There is no evidence that any Firm broker ever requested or coerced anycustomer to pay higher commission rates to receive IPO allocations, or for any other reason.Nonetheless, Enforcement concluded that between October 1, 1999, and March 31, 2000, theFirm had engaged in widespread misconduct by accepting commissions paid by customers whowere sharing with the Firm a portion of their real or hypothetical profits derived from the hotIPOs they received from the Firm. 118 Enforcement further alleged that the same customers madesimilar payments to other broker-dealers and received hot IPOs from those firms. 119 TheComplaint provided examples of the trades Enforcement questioned but did not identify theentire list of trades involving inflated rate commissions.Ultimately, Enforcement charged that the Firm shared in the profits in its customers’accounts in three ways: (1) by accepting commissions of 20 cents per share or more on trades of10,000 shares or more; 120 (2) by accepting commissions from two customers who engaged incross or wash trading; 121 and (3) by accepting high commissions from at least two customers whoflipped their IPO shares through the Firm at a substantial profit. 122117 JX 14 64-65 (Joint Stipulations).118 Compl. 1, 21, 23.119 Id. 22.120 Id. 21.121 Id. 34. Although Enforcement refers to “wash trading,” none of the trades met the definition of a wash sale.“‘Wash’ sales are transactions involving no change in beneficial ownership.” Ernst & Ernst v. Hochfelder, 425 U.S.185, 206 n.25 (1976). NASD Marketplace Rule 6440(b)(1) prohibits wash trades where they are made to create orinduce a false or misleading appearance of activity in a security or to create or induce a false or misleadingappearance with respect to the market in such security. Here, all of the sales involved a bona fide change ofownership.122 Id. 31-33.27

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.D. Enforcement’s Post-Complaint Development of its Profit-Sharing TheorySeveral months after Enforcement filed the Complaint, Enforcement retained Campbellas an expert to review the commission rates paid by the Firm’s customers. 123 Campbell testifiedthat he looked at the transactions Enforcement identified and then suggested that Enforcementshould develop additional metrics “to identify if there was something that was out of thenorm.” 124 Campbell thought that Enforcement needed to employ finer increments to analyze thetrades in question. 125 He therefore proposed additional metrics, which Enforcement adoptedwithout reference to the Firm’s specific policies and practices. 126 Campbell arrived at hissuggested metrics by what made good economic sense to him. 127 They are:1. $.20 per share or more on agency trades of 10,000 shares or more;2. $.20 per share or more on non-economic cross trades 128 of 5,000 sharesor more;3. If the customer’s trading activity included trades meeting one of theabove criteria, DOE also viewed as profit-sharing trades, any trades at acommission of $.75 per share or more on trades of 1,000 shares or more;[and]4. $1 per share or more on “flips” of 200 shares or more that the Firmallocated to the customer. 129123 Tr. 1661:12-24; 1688:20-24 (Campbell).124 Tr. 1662:5-12 (Campbell).125 Tr. 1670:10-13 (Campbell).126 Tr. 1671:8-12; 1705:23–1707:25 (Campbell).127 Tr. 1671:13–1672:11 (Campbell).128 Enforcement defined “non-economic cross trades” as those where a customer bought and sold the same numberof shares of a security at or about the same price on the same day. Tr. 200:3-6 (Ozag). At other points, Enforcementrefers to the same category of trades as “non-economic wash trades.”129 Bill of Particulars at 2 (emphasis in the original).28

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.Campbell saw the central issue as the problematic behavior of paying above-normalcommissions to get access to IPOs rather than profit sharing. Accordingly, he devised the metricsto identify the commission levels that made no economic sense unless the customer is assuredthat there will be an IPO allocation to justify the costs. 130 Thus, although the metrics defined“inflated rate commission payments,” the metrics rested on Campbell’s objection to customerscompeting for IPO allocations through increased commissions as opposed to increased orderflow. Campbell stopped short, however, of declaring all commissions within his metrics to beinherently excessive. Campbell recognized that sometimes a commission falling within themetrics could make economic sense. In his opinion, ultimately, whether or not a payment wasexcessive, and therefore constituted impermissible profit sharing, depended on what service thecustomer received in return for the higher-than-normal commission payment. 131 In that regard,Campbell testified that a customer could judge for itself the value of the services it receivedwithout conflicting with any conduct rules or regulations. 132Enforcement adopted Campbell’s suggestions. However, Enforcement determined thatthe Firm’s acceptance of any commission that fell within any of the enumerated criterionconstituted a per se violation of Conduct Rule 2330(f). That is, unlike Campbell, Enforcementdetermined that the commission levels evidenced profit sharing without regard to the Firm’s IPOallocation practices.130 Tr. 1681:25–1682:15 (Campbell).131 Tr. 1684:11-23 (Campbell).132 Tr. 1684:24–1685:5 (Campbell).29

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.E. The Alleged Profit-Sharing PaymentsEnforcement reviewed 9,621 agency trades placed by 1,364 customers at the Firmbetween October 1, 1999, and March 31, 2000. From this review, Enforcement determined that695 of the trades fell within the metrics it had formulated for this case and were, therefore,profit-sharing payments. Their classification as profit-sharing payments was not dependent upona finding that the Firm allocated IPO shares to the paying customers. Enforcement listed the 695trades on Amended Schedule A (“Schedule A-35”), 133 which Enforcement filed with its responseto [Respondent’s] Motion for a More Definite Statement. 134 The transactions sometimes arereferred to as the “Schedule A-35 trades.” 135The Firm earned total gross commissions of $4,133,013 on the Schedule A-35 trades,which equaled more than one-third of the Firm’s total agency commissions during the reviewperiod. 136 The weighted average of the commissions on the transactions is approximately 1% ofthe principal amount of the trades. 137Most of the Schedule A-35 trades fell into the first category of inflated rate commissionpayments—20 cents or more on transactions of 10,000 shares or more (“Type 1 Trades”), Ozag’soriginal criterion. Enforcement presented additional evidence, however, regarding two of theremaining categories Campbell formulated: non-economic cross or wash trades (“Type 2Trades”) and IPO flips (“Type 4 Trades”). Because these categories present distinct issues, thePanel discusses them in further detail below.133 CX 8.134 JX 14 14 (Joint Stipulations).135 JX 14 14 (Joint Stipulations). Exhibit CX 9 breaks out all of the agency trades by customer. Tr. 197:8-10(Ozag).136 Tr. 247:6-11 (Ozag).137 JX 14 22 (Joint Stipulations).30

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.1. Non-Economic Cross or Wash TradesJust six sets of trades placed by customers GAM and BRM fell into the category of Type2 Trades—20 cents or more on “non-economic cross trades” of 5,000 shares or more. 138Although Enforcement denoted the Type 2 Trades as cross or wash trades, they were neither. 139Indeed, Campbell did not consider Type 2 Trades to constitute “wash sales” or “cross trades.”Campbell testified that he formulated the criterion for Type 2 Trades to catch pairs of trades thathe considered the functional equivalent of Type 1 Trades. That is, he viewed the sale andpurchase of 5,000 shares of the same stock on the same day at commissions of 20 cents per shareor more as the equivalent of a single trade of 10,000 shares at a commission of 20 cents ormore. 140The Panel concluded that the Type 2 Trades were neither wash sales nor cross trades. Bydefinition, a “wash sale” involves no change of beneficial ownership, 141 whereas each sale heredid involve a bona fide change in ownership. And a cross trade entails a simultaneous match by asingle broker-dealer of a buy and sell order from two different customers. 142 Here, each sell orderwas executed in the marketplace through a different broker, and none of the “matched” tradeswas simultaneous.Calling the trades “wash” or “cross” trades inaccurately implied that the trades wereinherently improper. Indeed, Enforcement argued that, from the customers’ perspective, thetrades were economically irrational; thus, the Panel must conclude that GAM and BRM placed138 Id. 25, 31.139 Enforcement did not explain why it referred to the Type 2 Trades as cross or wash trades.140 Tr. 1799:7-17 (Campbell).141 See NASD Marketplace Rule 6440(b)(1).142 Tr. 252:18–253:2 (Ozag).31

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.the trades for an improper purpose—to generate commissions for the Firm’s benefit. 143 However,Green and Raha, Enforcement’s experts who addressed this subject, each testified on crossexaminationthat the Firm did nothing wrong in accepting the commissions on these trades. 144The Panel agrees.Enforcement did not present sufficient evidence to prove that the “inflated ratecommissions” on the Type 2 Trades were improper profit-sharing payments. Enforcement and itsexperts did not interview GAM and BRM or review their prime brokerage accounts.Consequently, Green and Raha could only speculate about the motives behind their trades. 145In addition, Enforcement’s assumption that the trades could only be explained as profitsharing is incorrect. As Enforcement concedes at other points, a customer may do extra businesswith, or pay higher commissions and fees to, a broker in order to be deemed a valued customer.From an economic perspective, this is a legitimate business strategy. And, where a customerinvests its own funds, as did GAM and BRM, such activity is not inherently improper. Unlike abroker or mutual fund, GAM and BRM were under no duty to trade at or near the lowest cost. Inshort, they were entitled to make their own business decisions about the value of the services theFirm provided. The fact that they placed a higher value on those services than Green and Rahawould have is not evidence of profit sharing.143 See, e.g., Enforcement’s Post-Hr’g Br. at 21.144 Tr. 1207:16-19 (Green); Tr. 2203:13-24 (Raha).145 For example, Raha states in his report that GAM appeared to be “engaged in day trading and did not like to takea lot of risk.” CX 36 at 11 (Raha report). Raha defined “risk” as a function of the volatility of the underlying asset,the holding period, and the security’s liquidity. Then, Raha concluded that GAM’s trades were of no “economicbenefit” because they deviated from the typical day-trading strategy. Raha drew this conclusion with no knowledgeof GAM’s operations as a whole. See CX 36 at 11-12 (Raha report).32

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.2. IPO FlipsEnforcement presented evidence regarding a single Type 4 Trade—a trade involvingreceipt of a commission of $1 or more per share on a flip of not fewer than 200 IPO shares. 146Customer JD flipped 200 shares of VA Linux stock on December 9, 1999. 147 Enforcement notedthat the VA Linux IPO was the hottest offering of the 1999–2000 IPO boom. JD purchased theVA Linux IPO at $30 per share and sold the same day at $270 per share, for a gross profit of$48,000. JD paid the Firm a commission of $1,600, or $8 per share. 148Enforcement claimed that the commission was a payment of a share of the profits in JD’saccount because the commission fell within the definition of a Type 4 Trade. The Panelconcluded however that the evidence did not support Enforcement’s conclusion.JD denied that he paid the commission to share profits with his friend and broker, CJ. 149JD testified that he considered CJ a unique resource with 50 years of experience in the securitiesindustry. 150 Over the years, JD relied on CJ’s advice, but JD set the commissions he paid CJindependently. 151As did some of the other customers who testified, JD generally set the amount of grosscommissions he paid brokers annually based on the relative value of the services they provided.146 Other Type 4 Trades appeared in Enforcement’s exhibits, but Enforcement did not present an analysis of any ofthose transactions.147 CX 10 at 4.148 Although the total commission was insignificant, the Panel concluded that Enforcement stressed this tradebecause of VA Linux’s extraordinary first trade premium and the magnitude of the commission rate JD placed onthe trade.149 Tr. 3057:13-17 (JD); accord RX 135 at 06933. In addition, JD testified that he did not consider the $8 per sharepayment to constitute underwriting compensation. Tr. 3062:18–3063:2; 3064:17–3066:4 (JD).150 Tr. 3047:3-9 (JD).151 Tr. 3057:19-21 (JD).33

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.On individual trades generally, JD was guided by NASD’s 5% Policy. 152 When questioned aboutthe VA Linux commission, JD explained that he considered three factors in setting thatcommission. First, he considered the flip of VA Linux an extraordinary event. He stressed thathe had never before made $48,000 in two hours. JD had given the trading desk the authority tosell at the open, using the trader’s best judgment. 153 Given the wild nature of the security, JDconcluded that he had received a “wonderful execution.” 154 Second, JD calculated that thecommission “was well under [NASD’s] 5-percent guideline.” 155 Third, JD considered that he hadpaid CJ less than the total amount budgeted for the year. 156 Thus, he used this extraordinary eventas an opportunity to increase the total.The Panel accepts JD’s testimony that he never considered sharing profits with the Firm.Although Enforcement attempted to discredit JD because he is a friend of CJ and KL, the Panelfound his testimony credible and reliable. In addition, the Panel notes JD’s long anddistinguished background in self-regulation of the securities industry. JD served as a member ofthe Corporate Bond Committee of the Securities Industry Association, as a hearing panelmember for the New York Stock Exchange (“NYSE”), as Chairman of NASD’s District 10Business Conduct Committee, as a member of NASD’s Board of Governors, as a member of152 Under the NASD’s Mark-Up Policy, IM-2440, mark-ups or spreads more than 5% above the prevailing marketprice in equity securities may be considered excessive, and thus violative of NASD Conduct Rules 2110 and 2440,unless justified in light of other relevant circumstances set forth in Conduct Rule 2440 and in IM-2440. See, e.g.,First Independence Group, Inc. v. SEC, 37 F.3d 30, 32 (2d Cir. 1994); District Bus. Conduct Comm. v. First Am.Biltmore Sec., Inc., No. C3A920018, 1993 NASD Discip. LEXIS 235, *19-20 (N.B.C.C. May 6, 1993). Althoughthe 5% Policy does not apply to agency trades of listed securities, brokers often refer to the policy when reviewingthe fairness of commissions charged on such transactions.153 Tr. 3053:8-15 (JD).154 Tr. 3055:6-25(JD).155 Tr. 3057:22-24 (JD).156 JD testified that he, like other institutional customers, set dollar volume targets for the commissions he wouldpay each broker per year.34

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.NASD’s National Business Conduct Committee, and ultimately as Chairman of NASD’s Boardof Governors. 157 The Panel finds no reason to question JD’s integrity.Accordingly, the Panel finds that the Firm did not share in the profits of JD’s account byaccepting the commission on the VA Linux transaction. In addition, the Panel finds thatEnforcement failed to prove that the commissions the Firm accepted on any of the other Type 4Trades were profit-sharing payments.F. No Customer Evidence of Profit SharingEach of the Firm’s customers that cooperated with Enforcement or otherwise providedevidence denied sharing profits with the Firm. They consistently denied profit sharing ininvestigative interviews, in written statements they and their counsel made, in hearing testimony,and in sworn on-the-record interviews taken by Enforcement during its investigation.1. April 2002 Telephone InterviewsIn April 2002, Enforcement’s investigator, Ozag, began calling some of the the Firm’scustomers in order to interview them. 158 Ozag testified, and his interview notes confirm, 159 thatthe customers he spoke to denied sharing profits with the Firm. 160 Indeed, they denied engagingin any of the questionable conduct about which they were asked, and they denied that the Firmhad engaged in improper conduct. For example, they denied that the Firm had ever asked them“to pay back a portion of [their] IPO profits.” 161 They also told Ozag that the Firm did not157 Tr. 3043:8–3045:17 (JD).158 Tr. 224:16–225:2, 343:4-6 (Ozag).159 Tr. 343:7-22, 351:10-14 (Ozag); RX 106 at 6199-6228, 6230-6239.160 Tr. 226:20-25 (Ozag).161 Tr. 344:23–345:6 (Ozag).35

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.“impose[] requirements on the customer in order to receive an allocation of hot issues”; 162 theypaid high commissions to be valued customers and obtain IPO allocations. 163 The customersfurther denied that the Firm “would accept higher than normal commissions on secondary tradesas payment in exchange for allocations,” 164 and denied that the Firm “would accept cash aspayment in exchange for allocations of hot issue IPOs.” 165 And the customers told Ozag that theFirm had not engaged in a quid pro quo. 1662. Customer Statements and MemorandaThe Firm submitted customer statements, affidavits, and counsel letters that wereconsistent with Ozag’s interviews. In September 2002, the Firm produced to Enforcement twobinders of materials reflecting its customers’ understandings of their dealings with the Firm; thefirst was a binder of statements signed by 23 customers, 167 and the second was a binder ofmemoranda reflecting interviews the Firm had conducted with 30 of its customers. 168 The162 Tr. 344:9-20 (Ozag).163 Ozag’s notes reflect how the customers explained that they were simply trying to be valued customers of theFirm. E.g., RX 106 at 6199, 6201, 6203, 6231-33 (“Broker for 18 yrs./ When I allocated IPOs, I did it to biggestaccount/ w/ that in mind, I wanted to be one of the accounts that would/ I wanted to be a big account because bigaccounts get IPOs,” “Tries to be a ‘competitive[’]/‘valued’ client,” “Factors influencing comm. rate/ Wants to be a‘valued competitive’ client,” “Wants to develop a relationship where the brokers are making [them] money—mayinclude getting IPO shares”).164 Tr. 345:11-18 (Ozag).165 Tr. 345:21–346:4 (Ozag).166 Tr. 350:9-14 (Ozag).167 RX 12.168 RX 13.36

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.statements were provided at the Firm’s request. 169 Each signed statement denies that any profitsharing, tie-ins, quid pro quos, or any conversations about these subjects had occurred. 170The 30 interview memoranda similarly deny the existence of any profit sharing, tie-ins,quid pro quos, or any conversations about these subjects. 171 Although the Firm solicited thesestatements, Ozag conceded that the customers would reaffirm the substance of their statementsunder oath if they were called to testify at the hearing. 172 Indeed, Ozag testified that three of thefour statements—that customers set commissions, that there were no tie-ins or quid pro quos,and that there were no discussions about tie-ins—were all categorically true. 173 And as for thefourth statement—the denial of profit sharing—Ozag conceded that the customers were beingtruthful: they did not believe they were sharing profits with the Firm, as they understood themeaning of the term. 174169 Tr. 227:8-13 (Ozag); see also JX 14 74 (Joint Stipulations).170 E.g., RX 12 at 2405. The form statements prepared for the customers by the Firm’s counsel “confirmed” thefollowing facts:1. At all times, I (or my representatives) unilaterally set the commissions on orders placed at theFirm.2. At no time was there ever any tie-in arrangement or quid-pro-quo linking commissions and IPOallocations.3. There were no discussions with the Firm suggesting or implying a tie-in arrangement betweencommissions and IPO allocations.4. I (or my representatives) did not engage in any profit-sharing with the Firm.171 E.g., RX 13 at 2456.172 Tr. 421:5-14 (Ozag).173 Tr. 422:3-12 (Ozag).174 Tr. 422:13–423:10 (Ozag).37

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.3. Customer AffidavitsIn addition, the Firm submitted seven customer affidavits that deny the existence of anytie-in arrangements, quid pro quos, kickbacks, or discussions about linkages betweencommissions and IPO allocations. 175 Enforcement introduced no evidence to contradict theseaffidavits.4. Customer Counsel LettersThe record also includes several exhibits containing various letters to Enforcement fromlawyers representing 14 customers. These exhibits show that these customers offered to confirmin interviews or affidavits that they had not engaged in profit sharing. 1765. Hearing TestimonyThree Firm customers—EB, JD, and SD—testified in person. Enforcement claims thattwo of them, EB and JD, shared profits with the Firm. 177 Both denied the charge.EB, who paid the most total commission dollars of all the other customers on ScheduleA-35, 178 consistently paid 60 cents per share on all his trades 179 although he paid other firms farless. He testified that he paid the Firm 60 cents per share because he valued KL’s advice. 180 In hiswords, KL “either saved me money or made me money.” 181 EB did not vary the rate dependingon the availability of IPOs, and he continues to pay 60 cents per share on all of his trades.175 RX 133-139.176 RX 116-123.177 The third customer, SD, did not purchase IPO shares from the Firm.178 See RX 312.179 JX 14 51 (Joint Stipulations).180 Tr. 4213:22–4214:3; 4236:7-15 (EB).181 Tr. 4218:5-8 (EB).38

This Decision has been published by the NASD Office of Hearing Officers and should be cited asOHO Redacted Decision CAF030014.When questioned about his motive in paying such a high rate, EB denied the existence ofany profit sharing, payback, tie-in, or quid pro quo. In addition, he stated that he had noconversations with the Firm about any of those subjects. 182As discussed above, 183 JD likewise denied sharing profits with the Firm. 184 As was thecase with other Firm customers, JD paid higher commissions to ensure access to the services theFirm provided him. Aside from access to IPOs, these included the investment advice he receivedfrom CJ, his broker, whom JD considered to be a uniquely valuable resource. The Panel creditsEB’s testimony and finds that the Firm did not share in the profits of his account.6. On-The-Record Interview TestimonyEnforcement took on-the-record testimony from several customers during theinvestigation; each denied sharing profits with the firm. 185 Of those, LM’s testimony isparticularly significant because Enforcement pointed to him as the customer who most supportedEnforcement’s profit-sharing theory. The Panel finds otherwise. LM’s on-the-record interviewtestimony actually undercuts Enforcement’s theory. 186LM is an unregistered professional investor who speculates in new issues for his ownaccount. 187 He disclaimed being an “investor,” by which he meant that he did not purchase stockto hold for the long term. 188 His business plan was to concentrate on IPOs. Thus, to maximize his182 Tr. 4215:9–4216:17 (EB).183 See Part III.E.2 at p. 30.184 See discussion infra Part III.E.2.185 Tr. 355:16–356:2 (Ozag).186 LM refused to testify at the hearing because he thought that Enforcement had mischaracterized his on-the-recordinterview testimony. See RX 240 at 10536-37 (LM Aff.).187 CX 38 at 22-23.188 Id. at 72.39