Summer - United States Special Operations Command

Summer - United States Special Operations Command

Summer - United States Special Operations Command

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

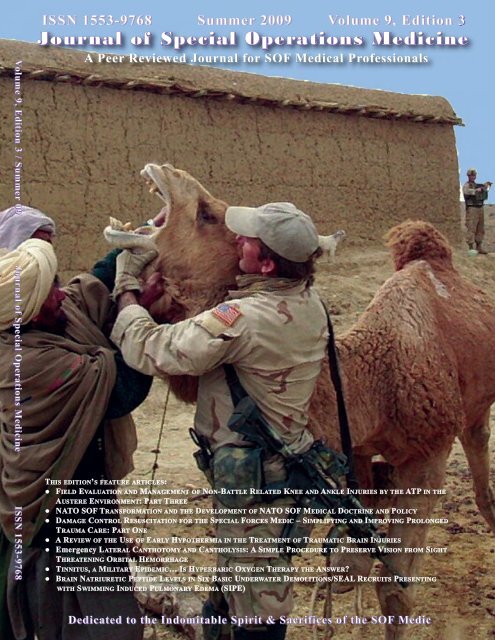

Volume 9, Edition 3 / <strong>Summer</strong> 09 Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Medicine ISSN 1553-9768ISSN 1553-9768 <strong>Summer</strong> 2009 Volume 9, Edition 3Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> MedicineA Peer Reviewed Journal for SOF Medical ProfessionalsTHIS EDITION’S FEATURE ARTICLES:● FIELD EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT OF NON-BATTLE RELATED KNEE AND ANKLE INJURIES BY THE ATP IN THEAUSTERE ENVIRONMENT: PART THREE● NATO SOF TRANSFORMATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF NATO SOF MEDICAL DOCTRINE AND POLICY● DAMAGE CONTROL RESUSCITATION FOR THE SPECIAL FORCES MEDIC – SIMPLIFYING AND IMPROVING PROLONGEDTRAUMA CARE: PART ONE● A REVIEW OF THE USE OF EARLY HYPOTHERMIA IN THE TREATMENT OF TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURIES● Emergency LATERAL CANTHOTOMY AND CANTHOLYSIS: A SIMPLE PROCEDURE TO PRESERVE VISION FROM SIGHTTHREATENING ORBITAL HEMORRHAGE● TINNITUS, A MILITARY EPIDEMIC… IS HYPERBARIC OXYGEN THERAPY THE ANSWER?● BRAIN NATRIURETIC PEPTIDE LEVELS IN SIX BASIC UNDERWATER DEMOLITIONS/SEAL RECRUITS PRESENTINGWITH SWIMMING INDUCED PULMONARY EDEMA (SIPE)Dedicated to the Indomitable Spirit & Sacrifices of the SOF Medic

Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> MedicineEXECUTIVE EDITORDeal, Virgil T. MD, FACSVirgil.Deal@socom.milMEDICAL EDITORGilpatrick, Scott, APA-C, DMOMANAGING EDITORLanders, Michelle DuGuay, MBA, BSNDuguaym@socom.milASSISTANT EDITORCONTRIBUTING EDITORParsons, Deborah A., BSNSchissel, Daniel J., MD(“Picture This” Med Quiz)CME MANAGERSKharod, Chetan U. MD, MPH -- USUHS CME SponsorOfficersEnlistedLanders, Michelle DuGuay, MBA, BSNMcDowell, Doug, PA-CDuguaym@socom.milDouglas.McDowell@socom.milEDITORIAL BOARDAckerman, Bret T., DOAnders, Frank A., MDAntonacci Mark A., MDBaer David G., PhDBaskin, Toney W., MD, FACSBlack, Ian H., MDBower, Eric A., MD, PhD, FACPBriggs, Steven L., PA-CBruno, Eric C., MDCloonan, Clifford C., MDColdwell, Douglas M., PH.D., M.D.Davis, William J., COL (Ret)Deuster Patricia A., PhD, MPHDiebold, Carroll J. , MDDoherty, Michael C., BA, MEPC, MSSFlinn, Scott D., MDFudge, James M., DVM, MPVMGandy, John J., MDGarsha, Larry S., MDGephart, William, PA-SGerber, Fredrick E., MMASGiebner, Steven D., MDGiles, James T., DVMGreydanus, Dominique J., EMT-PGoss, Donald L.,DPT, OCS, ATC, CSCSGodbee, Dan C., MDHarris, Kevin D., DPT, OCS, CSCSHammesfahr, Rick, MDTEXT EDITORSAckermann, Bret T. DO, FACEPBoysen, HansDoherty, Michael C., BA, MEPC, MSSGephart, William J., PA-SGodbee, Dan C., MD, FS, DMOVanWagner, William, PA-CJournal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Medicine Volume 9, Edition 3 / <strong>Summer</strong> 09Holcomb, John B., MDKauvar, David S., MDKersch, Thomas J., MDKeenan, Kevin N., MDKirby, Thomas R., ODKleiner Douglas M., PhDLaPointe, Robert L., SMSgt (Ret)Llewellyn, Craig H., MDLorraine, James R., BSNLutz, Robert H., MDMason, Thomas J. MDMcAtee, John M., PA-CMcManus, John G., MDMouri, Michael P., MD, DDSMurray Clinton K., MD, FACPOng, Richardo C., MDOstergaard, Cary A., MDPennardt, Andre M., MDPeterson, Robert D., MDRiley, Kevin F., PhD, MSCRisk, Gregory C., MDRosenthal, Michael D. PT, DScTaylor Wesley M. DVMTubbs, Lori A., MS, RDVanWagner, William, PA-CWedmore, Ian S., MD, FACEPWightman, John M., EMT-T/P, MDYevich, Steven J., MDHesse, Robert W., RN, CFRN, FP-CKleiner, Douglas M.Mayberry, Robert, RN, CFRN, EMT-PParsons, Deborah A., BSNPeterson, Robert D., MD

An 18D deworms a camel during a “Vet Cap” in Shkihn, Afghanistan.ISSN 1553-9768From the EditorThe Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Medicine (JSOM) is an authorized official military quarterly publication of the <strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> <strong>Special</strong><strong>Operations</strong> <strong>Command</strong> (USSOCOM), MacDill Air Force Base, Florida. The JSOM is not a publication of the <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> MedicalAssociation (SOMA). Our mission is to promote the professional development of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> medical personnel by providing a forumfor the examination of the latest advancements in medicine and the history of unconventional warfare medicine.JSOM Disclaimer Statement: The JSOM presents both medical and nonmedical professional information to expand the knowledge ofSOF military medical issues and promote collaborative partnerships among services, components, corps, and specialties. It conveys medicalservice support information and provides a peer-reviewed, quality print medium to encourage dialogue concerning SOF medical initiatives.The views contained herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the Department of Defense. The <strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> <strong>Special</strong><strong>Operations</strong> <strong>Command</strong> and the Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Medicine do not hold themselves responsible for statements or products discussedin the articles. Unless so stated, material in the JSOM does not reflect the endorsement, official attitude, or position of the USSO-COM-SG or of the Editorial Board.Content: Content of this publication is not copyrighted. Published works may be reprinted provided credit is given to the JSOM and the authors.Articles, photos, artwork, and letters are invited, as are comments and criticism, and should be addressed to Editor, JSOM, USSOCOM,SOC-SG, 7701 Tampa Point Blvd, MacDill AFB, FL 33621-5323. Telephone: DSN 299-5442, commercial: (813) 826-5442, fax: -2568; e-mailJSOM@socom.mil.The JSOM is indexed with the National Library of Medicine (NLM) and included in MEDLINE. Citations from the articles indexed,the indexing terms, and the English abstract printed in the journal will be included and searchable using PubMed. The JSOM is serial indexed(ISSN) with the Library of Congress and all scientific articles are peer-reviewed prior to publication. The Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Medicinereserves the right to edit all material. No payments can be made for manuscripts submitted for publication.Distribution: This publication is targeted to SOF medical personnel. There are several ways for you to obtain the Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong>Medicine (JSOM). 1) USSOCOM-SG distributes the JSOM to all our SOF units and our active editorial consultants. 2) SOMA membersreceive the JSOM as part of membership. Please note, if you are a SOMA member and are not receiving the subscription, you cancontact SOMA through http://www.trueresearch.org/soma/ or contact Jean Bordas at j.bordas@trueresearch.org. SOMA provides avery valuable means of obtaining SOF related CME, as well as an annual gathering of SOF medical folks to share current issues. The JSOMis also available online throught the SOMA website. 3) For JSOM readers who do not fall into either of the above mentioned categories, theJSOM is available through paid subscription from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), for only $30 ayear. Superintendent of Documents, P.O. Box 371954, Pittsburgh, PA 15250-7954. GPO order desk -- telephone (202) 512-1800; fax (202) 512-2250; or visit http://bookstore.gpo.gov/subscriptions/alphabet.html. You may also use this link to send a email message to the GPO Order Desk— orders@gpo.gov. 4) The JSOM is online through the Joint <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> University’s new SOF Medical Gateway; it is available to allDoD employees at https://jsoupublic.socom.mil/. Click on medical – Click on Journal Icon – Then click on the year for specific journal.We need continuing medical education (CME) articles!!!! In coordination with the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences(USUHS), we offer CME/CNE to physicians, PAs, and nurses. SOCOM/SG Education and Training office offers continuing educationcredits for all SF Medics, PJs, and SEAL Corpsmen.JSOM CME consists of an educational article which serves to maintain, develop, or increase the knowledge, skills, and professionalperformance and relationships that a physician uses to provide services for patients, the public, or the profession. The content of CME is thatbody of knowledge and skills generally recognized and accepted by the profession as within the basic medical sciences, the discipline of clinicalmedicine, and the provision of healthcare to the public. A formally planned Category 1 educational activity is one that meets all accreditationstandards, covers a specific subject area that is scientifically valid, and is appropriate in depth and scope for the intended physician audience.More specifically, the activity must:• Be based on a perceived or demonstrated educational need which is documented• Be intended to meet the continuing education needs of an individual physician or specific group of physicians• Have stated educational objectives for the activity• Have content which is appropriate for the specified objectives• Use teaching/learning methodologies and techniques which are suitable for the objectives and format of the activity• Use evaluation mechanisms defined to assess the quality of the activity and its relevance to the stated needs and objectivesTo qualify for 1 CME, it must take 60 min to both read the article and take the accompanying test. To accomplish this, your articlesneed to be approximately 12 ─ 15 pages long with a 10 ─ 15 question test. The JSOM continues to survive because of the generous and timeconsumingcontributions sent in by physicians and SOF medics, both current and retired. See Submission Criteria in the back of this journal.We are looking for SOF-related articles from current and/or former SOF medical veterans. We want articles that deal with trauma, orthopedicinjuries, infectious disease processes, and/or environment and wilderness medicine. Mostly, we need you to write CME articles. Help keep eachother current in your re-licensure requirements. Don’t forget to send photos to either accompany the articles, or alone to be included in the PhotoGallery associated with medical guys and/or training. If you have contributions great or small… send them our way. Our e-mail is:JSOM@socom.mil.Lt Col Michelle DuGuay LandersFrom the Editor

<strong>Summer</strong> 09 Volume 9, Edition 3FEATURE ARTICLESField Evaluation and Management of Non-Battle Related 1Knee and Ankle Injuries by the ATP in the AustereEnvironment: Part ThreeJ.F. Rick Hammesfahr, MDNATO SOF Transformation and the Development of 7NATO SOF Medical Doctrine and Policy.LTC G. Rhett Wallace, MD FAAFPDamage Control Resuscitation for the <strong>Special</strong> Forces 14Medic: Simplifying and Improving Prolonged TraumaCare: Part OneCOL Gregory Risk MD; Michael R. Hetzler 18DReview Article of the Use of Early Hypothermia in the22Treatment of Traumatic Brain InjuriesJess Arcure BS, MSc; Eric E. Harrison MDEmergency Lateral Canthotomy and Cantholysis: 26A Simple Procedure to Preserve Vision from SightThreatening Orbital HemorrhageCPT Steven Roy Ballard, MD; COL Robert W. Enzenauer,MD, MPH; Col (Ret) Thomas O’Donnell, MD; James C.Fleming, MD; COL Gregory Risk, MD, MPH, FACEP;Aaron N. Waite, MDTinnitus, a Military Epidemic… Is Hyperbaric Oxygen 33Therapy the Answer?LCDR Thomas M. Baldwin, MD, MPTBrain Natriuretic Peptide Levels in Six Basic UnderwaterDemolitions/SEAL Recruits Presenting with SwimmingInduced Pulmonary Edema (SIPE)LCDR Damon Shearer (DMO/UMO) MDCDR Richard Mahon (DMO/UMO) MDAbstracts from Current Literature 51Previously Published 59Contents● Central Retinal Vein Occlusion in an Army Ranger withGlucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency● Should We Teach Every Soldier How to Start an IV?● Psychological Resilience and Postdeployment Social SupportProtect Against Traumatic Stress and DepressiveSymptoms in Soldiers Returning From <strong>Operations</strong> EnduringFreedom and Iraqi Freedom● Psychosocial Buffers of Traumatic Stress, Depressive Symptoms,and Psychosocial Difficulties in Veterans of <strong>Operations</strong>Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom: The Role ofResilience, Unit Support, and Postdeployment SocialSupport44Editorials 79LTC Craig Myatt, PhD; Douglas C. Johnson, PhDBook Reviews 81● Blackburn’s Headhunters● The Battle of Mogadishu: Firsthand Accounts from the Menof Task Force RangerFrom the USSOCOM <strong>Command</strong> Surgeon 86COL Tom DealComponent Surgeons 87COL Peter BensonBrig Gen (S) Bart IddinsCAPT Jay SourbeerCAPT Anthony GriffayUSASOCAFSOCNAVSPECWARMARSOCTSOC Surgeons 92COL Rocky FarrSOCCENTCOL Frank NewtonUSASFC Surgeon 96LTC Andrew LandersSOCPACNATO Surgeon 97LTC Rhett WallaceUSSOCOM Psychologist 99LTC Craig Myatt, PhDUSSOCOM Veterinarian 101LTC Bill Bosworth, DVMNeed to Know 104Navy Safe HarborSOF Reading List 105Educational Resources 121Photo Gallery 127Meet the JSOM Staff 129Submission Criteria 130Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Medicine Volume 9, Edition 3 / <strong>Summer</strong> 09

Field Evaluation and Management of Non-BattleRelated Knee and Ankle Injuries by the ATP in theAustere Environment — Part ThreeJF Rick Hammesfahr, MDEditor’s Note: Part Three consists of ankle injury evaluation and taping.Part Two (taping procedures for the various knee injuries) was published in the JSOM Spring 09, Vol 9 Ed 2.Part One (evaluation of knee injuries) was published in the JSOM Winter 09, Vol 9 Ed 1.ANKLEThe most commonly injured ankle ligament isthe anterior talo-fibular ligament (ATFL) located at theanterolateral aspect of the ankle (Figure 58).Figure 59: Plantarflexion and inversion ofthe ankle leads to abnormal stretching andtearing of the anterior talo-fibular ligament(ATFL).Figure 58: Anterior talo-fibular ligament locationat the anterolateral aspect of the ankle.With respect to ankle sprains and injury to theATFL, the typical mechanism of injury involves a forcedmotion that is best described as a plantarflexion – inversiondeforming force (Figure 59).This injury is often accompanied by a history ofa pop; the patient often states that they rolled their ankle;there is pain and swelling with the most intense area ofsymptoms located at the anterolateral aspect of the ankle.When intact, the ATFL goes from the distal aspectof the fibula to the talus. In this position, it acts asa checkrein to prevent abnormal posterior subluxationof the tibia relative to the talus (Figure 60).Figure 60: Intact AFTL preventssubluxation of the tibia and fibularcomplex relative to the talus.Field Evaluation and Management of Non-Battle Related Knee and Ankle Injuries by the ATP in theAustere Environment — Part Three1

In testing for stability of the ATFL, which is amajor stabilizer of the ankle, an anterior drawer test isperformed. This is done much like the anterior drawertest of the knee. The knee is flexed to 90 degrees andthe foot is stabilized (Figure 61). By applying an anteriorlydirected force to the calcaneus, or by stabilizing thefoot, and then applying a posteriorly directed force to thetibia, the stability of the lateral ankle ligaments are tested.Figure 63: Torn ATFL with posterior tibia and fibula subluxation.Although xray stress views are shown for teachingpurposes, the posterior “clunk” as the bones sublux isreadily felt and may be visualized in most patients.Figure 61: Anterior drawer test of the ankle. With aposteriorly directed force applied to the tibia, and withthe foot stabilized, there is no subluxation of the tibiaand fibula posterior on the talus.If the ATFL is torn, the tibia and fibula will subluxposteriorly (Figure 62 and 63). It should be notedthat this test should always be performed with the kneeflexed. With the knee extended, there is false stabilitywhen doing the test.The treatment for an ankle sprain is to preventthe deforming forces of plantarflexion and inversion.This is performed by taping the ankle followed by administrationof non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication.Further evaluation upon return to base isabsolutely required. Most likely the mission can becompleted.ANKLE TAPINGJust as with the knee, the taping at the ankle beginswith applying anchoring strips. The anchoringstrips are usually overlapped by approximately 30-50%.This taping method is demonstrated using two colors oftape so that the overlap and position of the tape may bebetter appreciated. As with taping the knee, the skinshould be clean and dry. If possible, shave the hair priorto tape application. However, tape should NOT be appliedover open wounds.Start by placing the ankle in the neutral position,perpendicular to the lower leg (Figure 64).Figure 62: Torn ATFL with posterior tibia andfibular subluxation on the talus after applyinga posteriorly directed force.Figure 64: Start with the ankle perpendicular to theforeleg and everted if possible.2Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Medicine Volume 9, Edition 3 / <strong>Summer</strong> 09

The circumferential anchoring strips are appliedwith approximately a 30%-50% overlap (Figure65). Strips are applied at the metatarsal phalangeal regiondistally as well as approximately half way up theforeleg.Figure 67: Second hindfoot anchoring strip applied.Figure 65: Proximal and distal anchoring strips.Following the basic anchoring strips, U-shapedstrips are applied. When applying these strips, startproximally and medially. As the tape is applied, thehindfoot is pulled into eversion, to decrease the stresson the damaged ATFL region. This allows for stabilityof the ankle with respect to inversion and eversion (Figure66 and 67).After two of these strips have been applied,U-shaped strips are applied beginning at the medialaspect of the foot and then continuing posterior to theankle, ending at the distal lateral aspect of the foot.This aids in stability of forefoot adduction and aids instability of inversion (Figure 68 and 69).Figure 68: Initial horizontal foot/ankle anchoring strip.Figure 66: Pull tape strips from medial to lateral toevert the hindfoot.Figure 69: Second horizontal foot/ankle anchoringstrip.Field Evaluation and Management of Non-Battle Related Knee and Ankle Injuries by the ATP in theAustere Environment — Part Three3

After completion of these two strips, the anchoringstrips (or heel lock taping) to specifically resistinversion are applied. The tape is started at themedial aspect of the ankle (Figure 70).Figure 72: Pull the ankle into eversion as the tape isapplied to the lateral border of the heel and ankle.Figure 70: Start at the proximal medial ankle with theheel lock tape strip.Finally, continue to pull the heel into eversion asthe tape is pulled to the medial side of the foreleg (Figure73).Pull the tape across the plantar aspect of theheel (Figure 71),Figure 73: Completed application of the heel locktape strip.Figure 71: Plantar application of the heel lock.The heel lock tape strip essentially pulls theankle into a position of eversion which takes the stressoff the damaged ligaments. Once the first heel lock stripis applied, three or four more are then placed (Figure 74-76).As the tape is pulled proximally and laterallyacross the lateral border of the heel and ankle, the heeland ankle should be everted to further increase the efficiencyof the heel lock tape strip and thereby decreaseany stress on the injured ATFL region (Figure 72).Figure 74: Completion of second heel lock strip.4Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Medicine Volume 9, Edition 3 / <strong>Summer</strong> 09

In doing so, all the skin is closed and coveredwith tape with the exception of the open area at theheel. This is done because ankle injuries are associatedwith a lot of swelling. If there are any breaks inthe tape and if skin is allowed to “peek” through thetape, this area will develop a very painful tape blister,which in the austere environment runs the risk of becominginfected (Figure 78).Figure 75: Starting the third heel lock strip.Figure 78: Complete taping with the heel left open.Figure 76: Completion of four heel lock strips.Once these strips have been applied, additionalcircumferential strips are applied (Figure 77).This type of taping results in excellent stabilityof the ankle joint. Obviously, the patient cannot returnto totally normal activities although he shouldremain functional.To appreciate the amount of stability that tapingprovides, look at the amount of inversion possiblein the untaped ankle (Figure 79) as opposed to thetaped ankle (Figure 80).Figure 77: Circumferential anchoring strips appliedto the foreleg and foot.Figure 79: Significant inversion of untaped ankle.Field Evaluation and Management of Non-Battle Related Knee and Ankle Injuries by the ATP in theAustere Environment — Part Three5

Figure 80: Minimal inversion of taped ankle asdetermined by inability to invert ankle/foot andraise the1st MTP joint off of the floor.GENERAL PRINCIPLES AND GUIDELINESIn trying to anticipate return to activity, ideallythere is no swelling or effusion, the patient has fullrange of motion and approximately 90% of normalstrength. However, the treating ATP must be awarethat as swelling decreases, the pain decreases and themotion increases. This gives a very false sense of healing.In fact, the symptoms will often disappear approximatelyfour weeks prior to completion of healing.Obviously, this sets up the situation whereby the patientis relatively asymptomatic, the healing is immatureand not complete, and a premature return toactivity leads to an extremely high re-injury rate.In general, successful treatment of non-battlefieldrelated knee and ankle injuries, in the austere situation,so that the patient may remain functional, requires severalthings:• The ATP must understand the anatomy involved.• He must know the questions to ask to identifythe mechanism of injury.• The ATP must understand the taping principles.• He must recognize that the taping is designedto support the injured tissue and decrease thestress load on the injury. To determine thetype of taping and to apply it successfully, itis obviously necessary to have a high probability of a working diagnosis.• He must know the possible diagnoses affectinga joint given a set of physical findingsand a mechanism of injury• Most importantly, a minimum of six weeksof healing is required, regardless of what thepatient says or how the patient feels.• The absence of pain does not equal healing• All of the injuries discussed here are significantinjuries that absolutely require furthermedical evaluation upon return to base.REFERENCEPerrin, David. (2005). Taping and Bracing, HumanKinetics.This completes our three-part series.JF Rick Hammesfahr, M.D. graduated from Colgate University in 1973 and the College of Medicineand Dentistry of New Jersey in 1977. He was Chief Resident in Orthopaedics at Emory Universityfrom 1980-1982. In addition to receiving numerous surgical awards, he has been on the speaking facultyof numerous medical and orthopaedic meetings serving as the co-director of several courses onknee surgery. His publications have focused on tactical medicine, arthroscopy, calcaneal fractures, abductorparalysis, wound healing, running injuries, meniscal repair, septic knees, and sports medicine.He has written two book chapters, one book, published 22 articles, serves on the editoral review boardof multiple medical journals, is a chief editor of the “Ranger Medic Handbook,” and has presented over120 CME lectures and talks on orthopedics and sports injuries.Dr Hammesfahr has served as president of the largest regional orthopaedic association, the Southern OrthopaedicAssociation. Currently, he is the Director of the Center for Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine and serves as the Chairmanof the USSOCOM Curriculum and Examination Board.6Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Medicine Volume 9, Edition 3 / <strong>Summer</strong> 09

NATO SOF Transformation and theDevelopment of NATO SOF MedicalDoctrine and PolicyG. Rhett Wallace, MD, FAAFPABSTRACTThe North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Forces (SOF) Coordination Center(NSCC) is a new NATO memorandum of understanding (MOU) organization that is effecting rapid advancementin NATO’s ability to efficiently utilize SOF at the strategic/operational level. The NSCC’s lines ofdevelopment in communications information systems (CIS), education, training, and real life support to the InternationalSecurity Assistance Force (ISAF) SOF and the development of pivotal documents to develop and matureNATO SOF doctrine and policy are all occurring at lightning speed. Within this process of establishing aSOF community in NATO, the author’s focus is the development of previously non-existent NATO SOF medicaldoctrine and policy. Many barriers to change lie ahead, but through unity of effort, we will ensure certaintyof our actions.The focus of this article is to give a briefoverview of the development of the NATO SOF TransformationInitiative (NSTI), highlight the establishmentof the NSCC, and discuss the development ofNATO SOF medical doctrine and policy that willshape how NATO SOF operations are medicallyplanned and supported in current and future operations.The NSTI concept began in the spring of 2006as a multinational call to the Supreme Allied <strong>Command</strong>erEurope (SACEUR), the commanding officerof NATO’s Allied <strong>Command</strong> for <strong>Operations</strong> (ACO),Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe(SHAPE). Several nations saw a need to develop aSOF capability for NATO, addressing gaps in NATO’sability to strategically and operationally employ nationalSOF elements in a cohesive alliance or coalitionenvironment.While NATO is established in accordancewith Article 51 of the <strong>United</strong> Nations Charter as a politicalalliance with a military branch organized for collectivedefense, NATO’s focus has historically beenbased on the conventional aspects of the alliance’s militarypower. Because of this, NATO’s motivations forchange were the identified gaps in its “response to unconventionalthreats that recognize no national boundaries,show open contempt for human rights, andinternational rule of law.” 1 As a result, in November2006, at the Riga Summit in Latvia, President GeorgeW. Bush, as the Dean of the North Atlantic Council(NAC), announced the NAC’s endorsement of theNSTI, with the NSCC, frame-worked by the <strong>United</strong><strong>States</strong>, as the centerpiece. 2The NSCC was established as a coordinationcenter under a memorandum of understanding (MOU)to streamline its development and implementation. The<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> volunteered to be the framework nation,with Vice Admiral William McRaven, then the <strong>Command</strong>er,<strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> <strong>Command</strong> Europe(SOCEUR), in Stuttgart, Germany, as its first “dualhatted”Director. With an initial cadre of 17 personnelselected from the SOCEUR Joint Staff, the intent wasto build the NSCC at Stuttgart, where it would remainfor three to five years before relocating to SHAPE.However, realignment of organizations at SHAPE allowedthe NSCC to transfer much earlier than expected,and in the summer of 2007, it was moved toSHAPE. Today, the NSCC has a staff of 110 multinationalpersonnel, having reached initial operational capabilityin August, 2008, with full operationalcapability expected by the end of May 2009, along withthe arrival of anoher 32 personnel. Most recently, as aresult of the NATO Summit in Strasbourg, the NSCChas been tasked to plan for a way ahead to move beyonda coordination center and to establish a full SOFheadquarters for NATO.The mission of the NSCC is to enable and supportNATO <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Forces as the focalpoint for strategic SOF advice and operational planningto the NATO chain of command. This is accomplishedby providing subject matter expertise to theSACEUR and Joint Force <strong>Command</strong>s (JFCs) andtranslating strategic estimates into operational requirements.In addition, the NSCC is responsible for coordinationand synchronization of NATO SOF in theNATO SOF Transformation and the Development of NATO SOF Medical Doctrine and Policy7

force generation process, the development of NATO SOFpolicy and doctrine, and fostering interoperability andstandardization. In the area of interoperability, the NSCCfocuses on NATO SOF education, training, and exercises. 3The NSCC is aggressively accomplishing the goalsoutlined by the NAC and Military Committee. InitialNATO SOF operational concepts at the strategic and operationallevel were developed in the NSCC Handbook,and formalized in the development and ratification of theMilitary Committee’s documentation of NATO SOF Policyand Allied Joint Publication (AJP) 3.5. 4,5 Throughthese foundational documents, NATO has set the frameworkfor development of a SOF structure, doctrine, andpolicy. As one would expect, the complexities of coordinatingSOF from 23 different nations’ calls for concentratingon the basics. With this in mind, the missions ofNATO SOF are very straightforward. 61. SPECIAL RECONNAISSANCE AND SURVEILLANCE (SR)SR complements national and Allied theater intelligencecollection assets and systems by “obtaining specific,well-defined, and possibly time-sensitiveinformation of strategic or operational significance.” Itmay complement other collection methods where constraintsare imposed by weather, terrain-masking, hostilecountermeasures or other systems availability. SR is apredominately Human Intelligence (HUMINT) functionthat places “eyes on target” in hostile, denied, or politicallysensitive territory. SOF can provide timely analysisby using their judgment and initiative in a way that technicalintelligence, surveillance, target, acquisition,and reconnaissance(ISTAR) cannot. SOF may conductthese tasks separately, supported by, or in conjunctionwith, or in support of other component commands. Theymay use advanced reconnaissance and surveillance techniques,equipment, and collection methods, sometimesaugmented by the employment of indigenous assets.2. DIRECT ACTION (DA)These are precise operations that are normallylimited in scope and duration. They usually incorporatea planned withdrawal from the immediate objective area.DA is focused on “specific, well-defined targets of strategicand operational significance, or in the conduct of decisivetactical operations.” SOF may conduct these tasksindependently, with support from conventional forces, orin support of conventional forces.3. Military Assistance (MA)MA is a broad spectrum of measures in support offriendly forces throughout the spectrum of conflict. MAcan be conducted “by, with, or through friendly forces thatare trained, equipped, supported, or employed in varyingdegrees by SOF.” The range of MA is thus considerableand may vary from providing low-level military trainingor material assistance to the active employment ofindigenous forces in the conduct of major operations.4. OTHER MISSIONSOther missions include, but are not limited to,supporting counter-irregular threat activities, counteringchemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN)weapons, hostage release operations, and faction liaison.In order to manage the wide range of missionsand requirements, one of the first things the NSCC addressedwas the lack of a common CIS by developingand fielding a NATO SOF common CIS network. Fortunately,an existing system, called the Battlefield InformationCollection and Exploitation System (BICES),was already available within NATO. Intended to be usedfor the intelligence community, BICES proved itself asan ideal means for further expansion to support of NATOSOF operational activities. Because BICES has a NATOSecret and Unclassified version, it is ready-made as asystem for collaboration of all allied or coalition SOF.In addition, BICES offers the ability to allow non-NATOnations to participate, enabling an even greater fusion ofintelligence, and wider synchronization of operations.The development of hardware, software, and deployablecontainer packages for NATO SOF is now ongoing. Theintent is to expedite fielding to the ISAF SOF Headquartersin Afghanistan, supporting the already establishedISAF SOF Fusion Cell.On the interoperability front, the NSCC is addressingstandardization and interoperability of internationalSOF by the development of NATO SOF StaffOfficers Course, NATO SOF Combined Joint Forces<strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Component <strong>Command</strong> (CJFSOCC)Planners Course, NATO SOF Intelligence Course, aNATO <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Air Planners Course, and theNATO ISAF Pre-trainer Course. These courses are augmentedby products such as the CJFSOCC and <strong>Special</strong><strong>Operations</strong> Task Group (SOTG) Handbooks. Thesehandbooks cover the organization and staff functionswithin the CJFSOCC and at the SOTG level, their relationshipto other commands, and liaison roles and responsibilities.Other areas covered include SOFplanning, information operations, air support, targeting,battle tracking, intelligence, logistics, Force Health Protection(FHP), and communications. They provide toolsfor developing a common understanding of the CJF-SOCC and SOTG structure, implementation, responsibilities,and procedures within the Combined Joint TaskForce (CJTF) construct. As NATO SOF contributes to8Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Medicine Volume 9, Edition 3 / <strong>Summer</strong> 09

current and future operations, these tools will cultivatefuture development of NATO SOF doctrine and policy.To understand the basis for the foundationalwork in developing NATO SOF medical doctrine, wemust first understand NATO conventional medical support,and the gaps in NATO’s conventional health servicesupport (HSS) and FHP. NATO medical doctrinecan be reviewed in depth in AJP 4.10 and MC 326/2. 7NATO FHP is a patriarchal system primarily organizedaround fixed medical treatment facilities (MTFs) basedon Allied Nations HSS provided to NATO operations.NATO defines roles of medical care as:Role 1 is the lowest level at which a physiciantreats casualties. Role 1 provides advanced trauma/tacticalmedical care to stabilize and prepare casualties forevacuation to Role 2/3.Role 2 is the first level at which damage controlsurgery (DCS) is performed. Role 2 has two sub-categories:Role 2 Enhanced (Role 2E) – a “mobile” MTFthat it is put in place, but a logistical burden to moveonce in place, and Role 2 Light Maneuver (Role 2LM)– again a “mobile” DCS capability intended to supportInfantry or SOF. However, National Role 2LM is oftentoo heavy and immobile to adequately support infantryor SOF advancing on maneuvers.Role 3 is the level at which primary surgery islocated, and typically has advanced or sub-specialty surgicalservices associated. Role 3 MTFs generally providearea support within a Joint Operational Area (JOA).Role 4 is generally a national fixed MTF.NATO has standardization agreements(STANAGs) 8 and allied medical publications (AMedP) 9that address medical standards for individual trainingand equipment. These are currently being updated andspecifically identify or limit doctors as the personnel tobe trained with advanced medical techniques. AMedP-17 is the first NATO publication to recognize the term“medic,” and apply it to non-credentialed providers.Medic is not a formal definition in Allied AdministrativePublication-6 (AAP-6). 10 For example, Annex A2 11 outlineswhat medical procedures “Independent medics”may perform; these are by exception restricted to noninvasivetechniques. Annex B 12 refers to “doctors”when outlining minimum requirements for medicaltraining of medical personnel. Within NATO’s policieson individual training, many contributing nations do nothave civilian equivalent “medical providers” outside ofcredentialed doctors or nurses. This highlights variationsin acceptable standards of care within NATO; forexample, Nation “X” records reservations to AMedP-17 stating “medical and surgical treatment techniquescan only be applied by physicians.” 13As the Senior Medical Advisor (MEDAD) forthe NSCC, the author is working to establish a commondescription of NATO SOF medical capability, definingSOF medical doctrine and policy, developing a “scopeof practice” for SOF medics, and to provide guidance topromote the highest quality, evidence-based healthcarewithin NATO SOF. By defining NATO SOF medicalprofessionals, and providing a definition for standardizedSOF medical capability, the author is striving to establishstandards for NATO SOF medical professionalsto meet relative to educational preparation, professionalstanding, and technical ability. These standards are met,in part, by the application for – and maintenance ingood standing of – a license or certificate in nations thathave civilian equivalent medical care providers, and/ora NATO SOF Advanced Tactical Provider (ATP) typeregistration based on the proposed “scope of practice,”along with the ACO MEDAD and the Committee of theChiefs of Military Medical Services (COMEDS) guidanceon common medical standards and clinical governancein NATO. 14The author defines NATO SOF medical professionalindividual tasks using the Battle Focus Trainingmodel, basing essential core tasks on the unit’sMission-Essential Task List (METL). AJP 3.5 and MC437/1 provide the definition for NATO SOF elements,and authorize missions SOF will conduct under the alliance.NATO SOF are specially organized, trained, andequipped military forces to achieve military strategic oroperational objectives by unconventional militarymeans in hostile, denied, or politically sensitive areas.These operations are conducted across the full range ofmilitary operations, independently or in conjunctionwith conventional forces. Political-military considerationsoften shape SOF operations, requiring discreet,covert, or low visibility techniques that may include operationsby, with, and through indigenous forces.SOF operations differ from conventional operationsin the degree of physical and political risk, operationaltechniques, modalities of employment, andindependence from friendly support. Due to the natureof NATO SOF operating in remote, austere, at timesprimitive conditions, at the operational extremes, outsideof conventional forces direct or indirect support,SOF Soldiers and SOF medical professionals shouldpossess and maintain medical skills equal to and abovethose required to support conventional forces. It is criticalthat SOF Soldiers and SOF medical professionalsbe fully trained initially, and have robust medical sus-NATO SOF Transformation and the Development of NATO SOF Medical Doctrine and Policy9

tainment training programs on a broad spectrum of primaryand emergency medical care techniques, as wellas, preventive medicine, zoonotic and parasitic diseases,veterinarian care, dental care, CBRN, advancedtrauma, pharmacology, life saving or sustaining invasivesurgical and anesthesia techniques. These skillsare essential to provide adequate medical force protectionsupport for NATO SOF, and are the basis forpromoting SOF medical professional standardizedtraining and promoting interoperability of capabilityand medical equipment.Once established, NATO SOF medical trainingguidance will identify the essential components forindividual and collective medical training. Due to thebroad definition of SOF, specific SOF units will havedifferent training needs and requirements based on environment,location, equipment, dispersion, and similarfactors. SOF operating in a variety ofenvironments, such as hypo/hyperbaric conditions, extremesof heat and cold, mountains or high altitude,should augment the unit level medical training plan toaccount for medically relevant and specific diagnosisand treatments. Therefore, the SOF medical trainingguidance should be used as a guide for conducting unittraining, not as a rigid standard, and designed to assistthe commanders in preparing a SOF unit medical trainingplan which satisfies integration, cross-training, interoperability,and sustainment training requirementsfor NATO SOF medical professionals.Within the past 10 years, SOF LessonsLearned has contributed to advancement in medicalcare from point of injury to primary surgery. 15 Advances,such as SOF tactical combat casualty care(SOF TCCC) training, SOF individual first aid kits(SOF IFAKs), 16 and development of SOF evacuationkits to create casualty evacuation (CASEVAC) platformsout of transportation of opportunity to get casualtiesin austere environments to DCS, have beenpivotal in reducing died of wounds (DOW) rates forSOF Soldiers. 17 These advances are critical to providingadequate SOF HSS. Promoting the understandingthat advanced training and modernized equipment suchas the single handed tourniquet and haemostatic bandagesfor hemorrhage control is good, but DCS or primarysurgery is still required to addressnon-compressible hemorrhage to complete adequateSOF HSS for SOF casualties. Often conventional Role2/3 is unable to meet SOF HSS requirements due tothe great distance or the inflexibility of conventionalstructures to adapt to rapidly changing requirements;other issues revolve around non-existent/inadequatehost national medical support. SOF requires flexible innovativemedical planners to accommodate for gaps incapability. In light of this recurring issue multiple nationshave or are developing a Role 2 ultra-LM elementthat provides a truly light, maneuverable surgical andcritical evacuation team who are familiar with SOF missionsets, tactics and techniques, are operationally readon,small and light enough to maneuver with SOF, andunder the command and control (C2) of the SOF <strong>Command</strong>.The author defines this capability as Role 2 <strong>Special</strong><strong>Operations</strong> Surgical/Evacuation Team (Role 2 SOST).NATO comprehensive political guidance projectsan environment of change that “is and will be complexand global, and subject to unforeseeabledevelopments.” 18 SOF missions and operational conceptsare conducted across the range of military operationsthrough peacetime, conflict, various stages of war,and Article 5 collective defense or non-Article 5 CrisisResponse <strong>Operations</strong>. The SOF TCCC depends on anenhanced capability for first responders, SOF CombatMedic (SOCMs), SOF medical providers (SFMPs), andadaptive standard and non-standard platforms for CA-SEVAC in emergencies. Patients are CASEVAC’d tothe nearest host nation or Role 2/3 MTF capability, butSOF TCCC capabilities are of little benefit if there is notimely resuscitative surgical care available.As defined earlier, SOF operations by nature areremote, austere, and in primitive conditions at operationalextremes outside of conventional forces orfriendly direct or indirect support. SOF operate in smallteams and are often cross-trained in multiple skill sets toensure economy of effort and redundancy of capability.Advanced first responder training is essential for all SOFSoldiers. It is imperative that all SOF Soldiers be crosstrainedas medical first responders.SOF medical professionals can include a widerange of medical and paramedical professions. The followingdescriptions are included to assist in understandingthe capability that each medical professionalprovides as a combat multiplier.NATO in general does not specifically define the“medic.” Conventional medics have the skill sets to provideemergency care and entry level nursing care for patients.They attend a military/civilian medical trainingprogram that provides them with a certification (nationalor military) to provide medical care within their scopeof practice. Course content usually includes, but is notlimited to, trauma management, pre-hospital traumamanagement and care, basic life support (BLS), advancedlife support (ALS), and inpatient nursing skills.They can perform basic medical care under the supervi-10Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Medicine Volume 9, Edition 3 / <strong>Summer</strong> 09

sion of a physician, and limited preventive medicine.They can directly support combat units, ambulanceteams, or Role 1 medical support facilities. 19The author purposes creating a SOF CombatMedic (SOCM) as a new definition to be applied toNATO SOF medical professionals. A SOCM is a Soldiertrained in advanced medical care directly assignedor attached to SOF and who provides direct health servicesupport to <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Task Units (SOTUs)on operations. SOCMs are trained to initially treat andsustain a casualty from point of injury for up to 36 hoursbefore transfer of the casualty to MEDEVAC or nonstandardmedical treatment facility. SOCMs maintainthe skill set trained to medical first responders, commoncore tasks for conventional medics, advanced tacticalproviders 20 (the DA/SR medical skill sets), preventivemedicine, and environmental/tropical medicine. Initialtraining for SOCMs includes courses in basic humananatomy, basic human physiology, basic medical terminology,pharmacology calculations, and basic math.The SOCM course content should include, but is notlimited to, basic trauma management, pre-hospitaltrauma management and care, advanced trauma life support,BLS, ALS, inpatient/post-operative nursing skills,minor and invasive surgical procedures.The author also purposes creating a SOF medicalprovider (SFMP) as a new definition to be appliedto NATO SOF medical professionals. SFMP was chosento highlight the “independent provider” status of theadvanced training for a SFMP. A SFMP is a SOF Soldiertrained in advanced medical care, or a medical professionaldirectly assigned or attached to SOF and whoprovides direct health service support to SOTUs on operations.SFMPs are trained to operate independentlyfrom the direct supervision of a physician. SFMPs aretrained to initially treat and sustain a casualty from pointof injury for up to 72 hours, and in some mission sets foreven longer periods before transfer of the casualty toMEDEVAC or non-standard medical treatment facility.The SFMPs’ medical skill sets are based on the types ofpatients expected in a conventional forces environment,as well as those in hostile, denied, or politically sensitiveareas. By nature, SOF operations are conducted acrossthe full range of military operations, independently orin conjunction with conventional forces. Political-militaryconsiderations often shape SOF operations, requiringdiscreet, covert, or low visibility techniques thatmay include operations by, with, and through indigenousforces. SOF operations differ from conventionaloperations in degree of physical and political risk, operationaltechniques, modalities of employment, and independencefrom friendly support. These mission requirementsare the nexus for the following list of subjectareas and specific task that are core medical skills to beinitially trained and sustainment training requirementsfor SFMPs. Initial training requirements for SFMPs includeall of the training for SOCMs, with additionaltraining in primary, preventive medicine, anesthesia, andadvanced invasive procedures as described under “primarycare or emergency care doctor.” 21NATO SOFs’ ability to triage, treat, transfer,and recovery of casualties is critical to sustainment andregeneration of the force. Role 2 SOSTs will providethe ability to mitigate death from non-compressiblehemorrhage, the leading cause of death to SOF Soldierswho die of wounds. 22 The Role 2 SOST will be able toperform up to 10 DCSs without re-supply; manage twocritical care patients for up to 48 hours; perform en routecritical care for up to two patients at a time; and integrateseamlessly with SOF. 23SOF medical capabilities have been invaluable inestablishing rapport with allied and coalition regular andirregular forces, assisting the local populace, and counteringenemy propaganda about international motivesand intentions. SOF TCCC, SOCMs, SFMPs, and Role2 SOST capabilities enhance our ability to provide lifesaving treatment to combatants and non-combatants affectingthe outcome of any casualty situation. In additionto saving the lives of SOF Soldiers, coalitionpartners, and non-combatants, it plays a vital role acrossNATO SOF missions. The care provided to indigenouspeople is one of our strongest weapons in the battle for“hearts and minds.” It brings a universal message ofNATO as liberators rather than occupiers and gains popularsupport, willing cooperation, and intelligence. 24With an understanding of the current developmentin defining the capabilities for NATO SOF HSS,let’s review some identified areas that are resistant tochange, or may impede the progress of NSTI withinSOF HSS and FHP.Currently, no centralized knowledge base on allalliance and coalition SOF medical capability exists.The author intends to develop this information for medicalplanning and is continuing dialogue with contributingnations to establish this information. Establishingworking relationships with the ACO MEDAD, JFCs,ISAF, and national SOF medical staff will enable theNSCC to develop this working knowledge, and be ableto advise and assist NATO SOF planners on current andfuture operations.National strategic considerations have limitedwhat information some countries are willing to share inNATO SOF Transformation and the Development of NATO SOF Medical Doctrine and Policy11

egard to their capabilities. The NSCC will continue tofoster a climate of trust. Safeguarding national concernsis essential to information sharing within NATO.Currently, no standardized definition exists forNATO SOF non-credentialed providers. WhereasNATO has policies for doctors and nurses, it has restrictivepolicies for non-credentialed providers.NATO conventional non-credentialed medicalproviders are based on conventional medical supportsystems within MTFs in direct support of or in proximityto a credentialed providers. The author is gatheringnational input and consensus on the proposeddefinitions for NATO SOF medical professionals. Thiswork will be the foundation for development of initialand sustainment medical training requirements withinNATO SOF. The lack of a certain level of SOF medicalprofessional is not a sign of a nation’s inability tosupport SOF, but rather a planning consideration in theforce generation process.European Union and national policies currentlylimit advanced medical training and sustainmenttraining of non-credentialed providers who lack a recognizedcivilian equivalent medical provider. ManyNATO contributing nations have patriarchal civilianmedical systems, where the “doctor” is the primary decisionmaker and completes most invasive procedures;this is reflected in their concepts and policies relatingto HSS. Medical reforms within NSTI will revolvearound lessons learned and the realities of combat casualties’deaths that may ensue as the result of ColdWar medical polices and doctrine based around robusthost nation infrastructure and response. It is imperativethat a system be developed to enable the NSCC to bea gathering point of best SOF medical practices basedon lessons learned fed by input from SOF on currentand recent operations.Some contributing nations have limited or nopermanent medical staff within their national SOFcommand structures that limits their ability to effectivelyinfluence timely change. There are also nationalmedical structures that do not delegate authority ofSOF medical training requirements and points of instructionto their national SOF commands. This can beovercome by education of SOF specific medical requirements,best practices for joint level staffing/manning,SOF medical lessons learned, and best practicesto positively influence international chiefs of medicaldepartments, and mentor NATO SOF members whoare limited by people, funding, technology, or trainingrestrictions.The author will be engaging NATO’s conventionalmedical planners this spring at the NATO MedicalConference where he will highlight similarities andsignificant differences between NATO conventionaland SOF HSS capabilities and identify current gaps inrequirements. The intent will be to stimulate thought,generate dialogue, and make formal contact betweenthe NSCC and national SOF command level medicalstaff. At the NATO Medical Conference in the fall of2009, the author intends to engage NATO and Partnersfor Peace (PfP), SOF Surgeons, and medical plannersin a NATO SOF Medical Working Group (WG) to refineand further develop NATO SOF medical doctrineand policy. The development of an ongoing NATOSOF Medical WG will be reviewed at that time.This article gave a brief overview of the establishmentand development of the NSCC, and reviewedthe NSTI concept development. It proposedthe establishment of new NATO SOF definitions to defineSOF medical capability using the battle focusedtraining model. Through an understanding of the definitionof “SOF medical professionals,” sharing medicalintelligence resources, and identified best practicesfor medical support to SOF we can foster best practiceswithin NATO SOF. The article discussed the developmentof NATO SOF medical doctrine and policy, andreviewed some barriers to change. Lastly, it set anagenda for change over this coming year to establishrelationships between the NSCC and NATO <strong>Special</strong><strong>Operations</strong> medical staff at strategic and operationallevels. Please contact the author to provide input intothe development of NATO SOF medical doctrine andpolicy. Your contributions are critical to this effort andare essential to corporate understanding, improved interoperabilityand to establish NATO SOF common“capability” or definitions.12Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Medicine Volume 9, Edition 3 / <strong>Summer</strong> 09

REFERENCES1. James L. Jones, “A blueprint for change: TransformingNATO <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong>,” Joint Forces Quarterly; Issue45, 2nd quarter 2007, page 36.2. George W. Bush, remarks in Riga, Latvia, 28 November 2006.3. NSCC Handbook, 5 April 2009, page 7.4. Military Committee Decision 437/1, <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Policy,11 Jun 2006.5. Allied Joint Publications 3.5, Allied Joint Doctrine for <strong>Special</strong><strong>Operations</strong>, 27 January 2009.6. AJP 3.5, page 2-1 through 2-4.7. Allied Joint Medical Support Doctrine, 2002, and MilitaryCommittee Decision 326/2, NATO Medical <strong>Operations</strong>, 2006.8. STANAG 2126, Ed 5, First Aid Kits and Emergency MedicalKits. STANAG 2122, Ed 2, Medical training in firstaide, basic hygiene, and emergency care.9. Allied Medical Publication (AMedP) – 17, Training Requirementsfor Health Care Personnel in International Missions,10 March 2009.10. Allied Administrative Publication-6, dated 2008.11. AMedP-17, Annex A2.12. Ibid, Annex B.13. AMedP-17, page v.14. ACO MEDAD Medical Directive, October 2008.15. John B. Holcombe, et all, “Understanding combat casualtycare statistics,” The Journal of Trauma Injury, Infection, andCritical Care; 60:2, 397-401.16. Recommendations based on findings of the Committee onTactical Combat Casualty Care, July 2008.17. John B. Holcombe, et al. (2007). Causes of death in U.S.<strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Forces in the Global War on Terrorism,Annuals of Surgery;245: 6, June.18. NATO Comprehensive Political Guidance, endorsed by NATOHeads of State and Government on 29 November 2006.19. AMedP-17, Annex A2.20. Ibid, Annex B.21. Ibid, Annex A2.22. John B. Holcombe, “Causes of Death in U.S. <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong>Forces in the Global War on Terrorism,”23. USSOCOM Surgeons, CIPT for TSOST, 2009.24. Ibid.LTC Gary Rhett Wallace, MD, FAAFP, SFS, DMO is currently the Senior Medical Advisor andChief, NATO <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Coordination Center Medical Branch. He is Board Certified asa Fellow of the American Academy of Family Physicians. He has had the honor of working inoperational billets and for U.S. Army <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> <strong>Command</strong> for 12 years, serving as aBattalion/Flight Surgeon, Group Surgeon, and at the USASOC/USASFC level before being assignedto NATO. He also has spent three years as a Flight Surgeon for the 1/17 (Air) Cav, andthree years as a Clinic <strong>Command</strong>er in Europe. He has had three combat tours to Afghanistanwhere he served once as a Battalion Surgeon and twice as CJSOTF-A Surgeon.LTC Wallace, can be reached at COM: +32 65 44 8262; DSN: 314 423-8262; or by emailat unclassified: Gary.wallace@nscc.bices.org; NATO Secret: wallagr@nsn.bices.org; U.S. SIPR:gary.rhett.wallace@eur.army.smil.milNATO SOF Transformation and the Development of NATO SOF Medical Doctrine and Policy13

Damage Control Resuscitation for the<strong>Special</strong> Forces Medic:Simplifying and Improving ProlongedTrauma Care: Part OneCOL Gregory Risk MD; Michael R. Hetzler 18DABSTRACTCurrent operational theaters have developed to where medical evacuation and surgical assets are accessiblein times comparable to the <strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong>. While this has been an essential tool in achieving the best survivabilityon a battlefield in our history, the by-product of this experience is a recognized shortcoming in currentprotocols and capabilities of <strong>Special</strong> Forces medics for prolonged care. The purpose of this article is to providea theory of care, identify training and support requirements, and to capitalize on current successful resuscitationtheories in developing a more efficient and realistic capability under the worst conditions.Our forces enjoy high confidence in rapid casualtyevacuation and surgical intervention thanks tothe proximity and availability of those assets in today’sdeveloped theaters. While prehospital care hasevolved to an exceptionally high standard due to thesecapabilities, the ability of <strong>Special</strong> Forces (SF) medicsto conduct independent and prolonged care has sufferedbecause of them. Past experiences and futurepossibilities will require a return to prolonged, sustainedcare, as well as the development of new standardsfor all <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Forces (SOF) medicsbased on the latest and proven theories. This capabilitycan have significant application in today’s missionsranging from Foreign Internal Defense in austere environments,a distant outstation isolated by weather, a<strong>Special</strong> Reconnaissance patrol inaccessible due to conditionsin a mountain range, or even in short-term directaction missions when cut off from friendly forcesand support. We can also take lessons from the recentIsraeli invasion of southern Lebanon in 2006 whenboth conventional and <strong>Special</strong> Forces medics wereforced into long term care. In this example of a modernlow intensity conflict, even casualty evacuationover short distances was limited due to battlefield dynamics,troop disposition, and terrain. 1Critical care and resuscitation between pointof injury and surgical intervention may be the missingelement here, and should include the capacity for extendedcare, delayed hand-off, and late surgical success.Prehospital care is relative to the situation. Formost, it is only the treatment given at the point of injuryimmediately prior to hand-off to an evacuation platform.In <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> those lines are neither soclear nor so rapid; the scope and duration of care providedby SF medics may equate to that of a physicianat more than one conventional level. Prehospital carefor operations in austere environments includes: pointof injury, evacuation concerns, resuscitation, prolongedcare, as well as all the skills required of those (Figure1). Sustaining a patient in an operational environmentfor days post-event is no easy task. And while maintenanceof a casualty for 72 hours post-op is requiredtraining at the <strong>Special</strong> Warfare Center, the focus here isthe implementation of current and proven strategies tomaximize the patient’s chances of survival.Figure 1: The stages of care differ remarkably not only dueto the assets involved, but by the scope of care requiredfrom SF medics and Independent Duty Corpsmen whencompared to conventional systems.14Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Medicine Volume 9, Edition 3 / <strong>Summer</strong> 09

This article is the first of two meant to providean approach to critical care using damage control resuscitation(DCR) as a guideline adapted for our use. DCRis a current and proven practice and provides aggressiveand effective trauma management with minimal supportwhile preparing the patient for the next level of care.DCR consists of two parts: first, keeping blood pressureat approximately 90mmHg, and second, to rapidly reversecoagulopathy and restore oxygen carrying capacitywith fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and packed red bloodcells (PRBC). 2 Since FFP and PRBCs are unavailablefar forward, we are advocating the earlier and more aggressiveuse of type-specific fresh whole blood (FWB) asthe only workable solution for salvaging patients withlife-threatening injuries. Fresh whole blood delivers normalphysiological ratios of essential elements, with moreactive clotting factors than banked component blood, andat normothermic temperatures. 3 Indications for FWB useis based on patient presentation and lab results such aslactate, base deficit, pH, and hematocrit which will alsolater serve as endpoints in resuscitation, ensuring efficienttherapeutic objectives. While “balanced” or “hypotensive”resuscitation works well in the short term, apatient left hypotensive and under-resuscitated for a prolongedperiod cannot be sustained. Trauma patients whodo not normalize their pH or base deficit have significantlyhigher mortality at 24 hours and near universalmortality at 48 hours. 4Patient care in the austere environment is incomparableto that in a U.S. hospital. With that in mind,the scope of practice, therapeutic guidelines, proceduresused, benefit vs. risk analysis, and clinical tenets, significantlydiffer from a civilian emergency room or eventhat of a combat surgical hospital (CSH). Many mayquestion the standards of care recommended, but theyprobably do not appreciate the challenges SF medicsface. Prolonged care in the primitive setting cannot supportcurrent hospital-based parameters, and a return tounconventional warfare practices is warranted and necessary.Strict clinical practices are respected and exercised,but not always attainable in our environment.Careful review of many long forgotten practices fromprevious conflicts may yield surprising results. The useof tourniquets, damage control surgery, and plasma andwhole blood transfusions, are all being resurrected withimproved patient outcomes in the 21st century. Many believethe most difficult challenges are found in the austereenvironment, and this may be where DCR is of mostbenefit.The following recommendations to SF medic’swere gathered from a number of physicians and institutionsthat have compiled an impressive bank of credibleand groundbreaking theories over the last seven years.Our effort here is to capitalize on those lifesaving protocols,merge the conventional levels of care with ouroverlapping SOF capabilities, and apply them in our rigorousenvironment.OVERVIEWThe Tactical Combat Casualty Care Committee(TCCC) has continually updated guidelines since 1996for prehospital care on the battlefield as defined in threelevels: Care Under Fire, Tactical Field Care, and TacticalEvacuation Care. These guidelines are based onmedic, corpsman, and physician input and experiencesthrough quarterly conferences. However, TCCC guidelinesonly provide the basis for care at the point of injurythrough evacuation. This article maintains those guidelines,but will leave initial management behind as SFmedics move on to 12 to 96 hours post event.Damage control surgery (DCS) is a well establishedand proven modality of medical intervention inboth civilian and military practice. 5 The U.S. Army Instituteof Surgical Research (ISR) has provided the mostup-to-date collection, evaluation, and development ofcritical care for war wounded, and additionally hasdriven implementation of this theory within all the services.Damage control focuses on principles that allowfor highly efficient care while compensating for inexperienceand limited resources as the “great equalizer” oftrauma surgery. 6 Using the damage control model for aship, the goal is to rapidly implement measures that preventfurther deterioration before irreversible injury occurs,or “the ship sinks.” Most initial treatments aretemporary to minimize patient exposure to stressful surgicalconditions and to reduce a physiological loss whichmaximizes the patient’s preparation for more extensivecare. Definitive surgical repair of injuries prior to adequateresuscitation may lead to a fully repaired but unsalvageablepatient. The primary and most immediategoal is surgical control of hemorrhage with judiciousfluid resuscitation, which is accomplished with a numberof advanced surgical procedures such as rapid closure,shunting, or packing. Stopping furthercontamination through exploration and additional therapeuticserves as a concurrent effort and significantlydecreases septic effects that can impact mortality overtime. The patient then moves to the intensive care unitto receive resuscitative care preparing him for return tothe operating room within 24 to 48 hours for definitivesurgical repair. Understanding this entire process isparamount to “act tactically, but think strategically” 7 inpreparing patients for a successful outcome. This treatmentstrategy must be understood to prepare the patientDamage Control Resuscitation for the <strong>Special</strong> Forces Medic:Simplifying and Improving Prolonged Trauma Care: Part One15

at this level; the SOF medics primary goal is to ensure thatthe patients arrive at surgical assets properly resuscitated.Figure 2: The lethal triad easily visualized, attributed toColonel John Holcomb.Damage control resuscitation guidelines arespecifically focused on the prevention of the “lethal triad”consisting of hypothermia, coagulapathy, and acidosis; allof which can be either mutually supporting or mutuallydestructive (see Figure 2). The factors of the lethal triadare all proven independent and codependent indicators ofmortality which also apply to DCS. Damage control resuscitationguidelines also include aggressive hypotensiveand hemostatic resuscitation while providing parametersfor addressing all three areas of the lethal triad. Ensuringthat these efforts are proactive and continuous from thepoint of injury provides the most efficient care possibleand uses a more scientific and therapeutic approach tocombat trauma for SOF medics. Again, the medics carecan and should potentiate success in supporting bothTCCC and DCS in the hospital.Figure 3: An OSS doctor conducts minor surgery in China circa 1944.(Courtesy USASOC Historian’s Office)IMPORTANCE OF HEMOSTASISThe single most essential weapon for DCR isimmediate and effective hemostasis, and it is at the pointof injury where resuscitation begins for the SOF medic.Hemorrhage control is the conservation of every singledrop of blood and with it every key ingredient that providessuccess against the lethal triad. The loss of bloodleads to hypoperfusion of tissues, relative hypoxia, andpromotes anaerobic metabolism. This subsequentlypromotes acidosis, hypothermia, and loses key coagulationfactors that are not easily reclaimed. Minimizingblood loss by immediate and effective treatments is afundamental trauma skill. Perfecting the basics willgain hemorrhage control in the least amount of time andwith minimal supplies while increasing survivabilitywith DCR.The physiologic picture resulting from hemorrhageeasily demonstrates the interacting and accumulatingfactors that will be important later. Blood lossnot only includes red blood cells essential for tissueoxygenation but also critical coagulation componentssuch as platelets, clotting factors, and enzymes. Currentlythese factors can only be replenished in the mostdifficult procedures for the SF medic, especially whentime, enemy situation, and supplies may all be at odds.A loss of blood volume reduces total oxygen carryingcapability, which is compensated by increases in bothinotropic (contractility) and chronotropic (heart rate) effortuntil the mismatch in oxygen delivery and demandresult in tissue hypoxia, or true shock. At this point, theaffected tissues convert from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism,which exacerbates all three components of thelethal triad. Cellular hypoxia results in a 90%reduction in energy production and an increasedrate of lactate production promotingmetabolic acidosis. This action leads to cellularswelling and edema, which further diminishescapillary flow and microcirculationirrespective of mean arterial pressure (MAP).Additional hypoperfusion due to vasoconstrictionoccurs naturally and simultaneously bylowered blood pressure, pain, and corticalrecognition of injury. A lack of blood supplyto the liver results in decreased glucose andclotting factors further complicating coagulapathies.Other physiological damage occurswhen pro-inflammatory mediators are releaseddue to hemorrhage and tissue damage, andshock affects neuroendocrine responses producingsevere metabolic changes. 8Direct pressure is always the first step forhemostasis. As soon as hemorrhage is noted, dig-16Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Medicine Volume 9, Edition 3 / <strong>Summer</strong> 09

Figure 4 : A <strong>Special</strong> Forces medic conducts an I & Dprocedure in Bolivia in 1967.(Courtesy USASOC Historian’s Office)ital or manual pressure is paramount and almost alwaysassures immediate effectiveness. Remember, the goalis not just to limit the amount of blood loss, but to saveevery single drop possible. Paramount towards this endis the expectation that each Soldier, if able, performsself-care. This requires mental preparation, musclememory, and psychological hardening to perform underphysical pain, stress, and challenging conditions. Pressurepoints are next, or act as an adjunct to minimizeblood loss and always attempt to use other Soldiers todeal with pressure points even under the best circumstances.The benefit is reduced time to hemostasis andpreserved blood volume, while maintaining combatpower during the fight. Other essential multipliers includethe medic placing pressure with his own kneewhile he works, or effective support from his teammatesfrom prior cross-training or on-scene instruction.Tourniquets are extremely effective in the treatment ofextremity wounds and their success since 9/11 is inarguable.There have been no reports of amputations duringthe conflict directly attributable to tourniquet usage.Remember that bleeding control is a graded response,so if a limb is mangled enough a tourniquet will likelybe the first step in hemorrhage control. 9 Tourniquet effectivenessis based on the principles of ensuring theyare placed proximal to the wound, active bleeding stops,the distal pulse is absent, and that reassessment is frequentand continuous. Keep in mind that the durationa tourniquet is applied will bring new concerns in prolongedcare. Present standards call for removal withintwo hours and, if conscious, the patient will remind themedic of this with the pain that normally accompaniesprolonged tourniquet use. Application over two hourscan also predispose the patient to increased morbiditysuch as fasciotomies and amputations, all of which maylater be the medic’s responsibility in this scenario. 10Converting a tourniquet to an effective pressure dressingas soon as possible while leaving the tourniquet looseand in place, for use if reapplication is necessary, willlikely prevent issues later in prolonged care.Packing wounds is a science in itself, requiringeffective technique, proper supplies, and completed witha pressure dressing to optimize the medic’s work. Makingthe decision to pack early is important too; packingis dependent on the patient’s ability to form good clotsand if too many factors are lost, then packing will notbe effective. Bowl-type wounds must be addressed immediatelyby packing with a maximum of two fingersusing unrolled Kerlix® and working from the bottom ofthe wound up, left to right or circumferentially, as if fillinga bucket. Finding and addressing all potential spacein the wound to ensure that there is no opportunity forany leakage of blood is a difficult task, especially whilepacking blindly, in the dark, and under stress at speed.An effective packing job can provide hemostasis with aminimum amount of supplies. Packing should not onlybe reserved for bowl-type wounds but also used inanatomical girdle areas such as the groin or shoulder.Hemostatic agents provide additional tools for more difficultwounds but they require thorough training, ideallyduring predeployment trauma training, to utilize effectively.The same rule applies for hemostatics as withpacking: hemostatics + packing + pressure = success.Future technologies that are presently being developedfor advanced hemostatics such as vessel closure andpressurized viscotic hemostatics may offer additional adjunctsin time.PREVENTION OF HYPOTHERMIAWithin the lethal triad itself, the prevention ofhypothermia is probably the simplest and most practicedeffort for SOF medics. Hypothermia has significant effectsand yields 100% mortality to severely traumatizedpatients with core temperatures less than 90ºF (32ºC). 11The goal is to maintain the casualty’s core temperature togreater than 95ºF (35ºC). Preventing hypothermia takesfar less effort and time than attempting to treat it undercombat conditions.Temperature monitoring should be as continuousas possible. Use every tool in sequence from skincolor and extremity warmth, patient feedback, and mentation.Objective findings can be obtained from toolsDamage Control Resuscitation for the <strong>Special</strong> Forces Medic:Simplifying and Improving Prolonged Trauma Care: Part One17

such as inexpensive temperature dots placed on the foreheador intermittent temperatures taken with an oto-thermometer,or use a digital rectal thermometer forcontinuous and high confidence readings. The fact thatmost wounded patients very often feel cold post-insultor the observance of spontaneous shivering, should alwayskey the medic in to the above steps. In short, simplytreat every single patient relentlessly forhypothermia.Hypothermia prevention should start immediatelypost-injury. Consideration of heat loss goes handin-handwith the initial assessment and optimally shouldoccur during the primary survey or just immediatelythereafter. Most of this work can be accomplished bycross-trained teammates automatically and simultaneouslyas the medic treats. Plan, prepare, and practicehypothermia prevention during all aspects of training;immediately insulating patient contact with the ground,minimizing exposure during the primary exam, removingonly wet clothing, and even keeping the patient cleanare all essential principles decreasing heat loss. Useevery opportunity to get the patient off the ground, driedif possible, covered, and out of the elements and beginall proactive efforts for economy of time.Both passive and active measures should beplanned for. Standard commercial hypothermia kitsshould include a durable and effective solar blanket anda chemical warming blanket, and these should be keptwith litter kits. Open the warming blankets first as theynormally take some time to reach its full exothermic reaction.The solar blankets are normally vacuum sealedso it should be stretched to full size to open any incorporatedair cells. Position it diagonally on the litter sothat the head and feet lie on the longest ends of the blanketand move the casualty to the blanket as quickly aspossible to get him off the ground and negate conduction.The patient should then be “burrito” wrapped withthe blanket as tightly as possible; it is the air closest tothe patient, or within the air cells of the blanket, that providesthe insulation for heat retention. Trapped air betweenthe patient and the blanket is warmed by the bodyand then retained and protected from loss or change bythe blanket. If standard hypothermia kits are not available,wool or space blankets wrapped in the same mannerand with some kind of head insulation (up to 60%heat loss here) such as a wool skull cap will providemuch of the same effects.Active warming measures require prior planningand usually cannot be achieved through improvisation.The chemical warming blanket opened firstshould be laid between the patient and the solar blanketto provide some degree of active heat on all patients. Beaware that there are differences in products and manufacturersso always rehearse this procedure. There aremany different types of commercial kits and each hasvarying temperatures, durations, and effectiveness.Warming all fluids before giving should be the goal nomatter what type, route, or environment. IV warmerssuch as the enFlow® warming system or the ThermalAngel® have proven effective, but both have specificsthat need to be appreciated in the tactical environment.A significant amount of heat can be lost through theadministration line. Using a closed-system kept next tothe patient with minor infusion pressure, or protectingthe administration line with insulation and minimizingits exposure to the elements, is important. Althoughthe lack of a fluid warmer does not preclude establishingIV/IO access or administering appropriate fluids,witholding warm fluids is of detriment to the patient.Primitive warming in an austere environmentcan be simple and is limited only by the medic’s imagination.Using vegetation to insulate patients from theground, finding civilian blankets from a house, simpleshielding or overhead cover from the elements, heatbottles and active heat sources, and proper nutritionwould all be beneficial. Primitive means to warmingfluids such as using MRE heaters packaged in plasticbags are effective as well, but must be rehearsed andlearned. Body bags, although not without possible psychologicaleffect, are extremely effective in heat retentionand protection and have been used in greatsuccess in Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) andOperation Iraqi Freedom (OIF).Expedited evacuation has become the norm inOIF, but exists as a double edged sword. Timely evacuationmitigates the environmental effects of prolongedFigure 5: A Detachment 101 surgeon works on woundedin an austere environment during World War II.(Courtesy USASOC Historian’s Office)18Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Medicine Volume 9, Edition 3 / <strong>Summer</strong> 09