Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

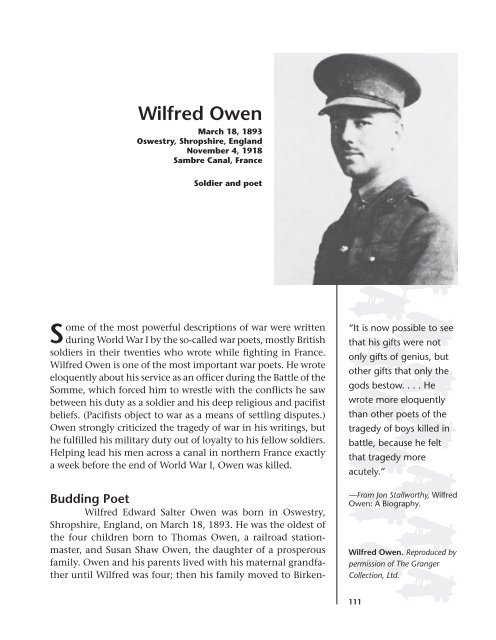

<strong>Wilfred</strong> <strong>Owen</strong><br />

March 18, 1893<br />

Oswestry, Shropshire, England<br />

November 4, 1918<br />

Sambre Canal, France<br />

Soldier and poet<br />

Some of the most powerful descriptions of war were written<br />

during World War I by the so-called war poets, mostly British<br />

soldiers in their twenties who wrote while fighting in France.<br />

<strong>Wilfred</strong> <strong>Owen</strong> is one of the most important war poets. He wrote<br />

eloquently about his service as an officer during the Battle of the<br />

Somme, which forced him to wrestle with the conflicts he saw<br />

between his duty as a soldier and his deep religious and pacifist<br />

beliefs. (Pacifists object to war as a means of settling disputes.)<br />

<strong>Owen</strong> strongly criticized the tragedy of war in his writings, but<br />

he fulfilled his military duty out of loyalty to his fellow soldiers.<br />

Helping lead his men across a canal in northern France exactly<br />

a week before the end of World War I, <strong>Owen</strong> was killed.<br />

Budding Poet<br />

<strong>Wilfred</strong> Edward Salter <strong>Owen</strong> was born in Oswestry,<br />

Shropshire, England, on March 18, 1893. He was the oldest of<br />

the four children born to Thomas <strong>Owen</strong>, a railroad stationmaster,<br />

and Susan Shaw <strong>Owen</strong>, the daughter of a prosperous<br />

family. <strong>Owen</strong> and his parents lived with his maternal grandfather<br />

until <strong>Wilfred</strong> was four; then his family moved to Birken-<br />

“It is now possible to see<br />

that his gifts were not<br />

only gifts of genius, but<br />

other gifts that only the<br />

gods bestow. . . . He<br />

wrote more eloquently<br />

than other poets of the<br />

tragedy of boys killed in<br />

battle, because he felt<br />

that tragedy more<br />

acutely.”<br />

—From Jon Stallworthy, <strong>Wilfred</strong><br />

<strong>Owen</strong>: A Biography.<br />

<strong>Wilfred</strong> <strong>Owen</strong>. Reproduced by<br />

permission of The Granger<br />

Collection, Ltd.<br />

111

The Poets of World War I<br />

Since ancient times, poets of every<br />

culture have made war and soldiering<br />

important subjects of their work, in epic<br />

poems (long poems) that celebrate heroic<br />

exploits, in lyrics and odes that honor the<br />

courage of the warrior, or in pacifist works<br />

that criticize the brutality and horror of<br />

war. Some of the finest verses in the<br />

history of English literature were written by<br />

poets who served in World War I, many of<br />

whom died in combat while still in their<br />

twenties.<br />

The following men are among the<br />

most prominent of the British war poets:<br />

Rupert Brooke (1887–1915): After<br />

brief noncombat duty in Belgium, he died<br />

of an infection caused by a mosquito bite;<br />

he was serving in the Greek islands at the<br />

time. A sequence of sonnets (poems with<br />

fourteen lines and a definite rhyme pattern)<br />

titled 1914 contains his most famous lines:<br />

“If I should die, think only this of me: /<br />

That there’s some corner of a foreign field /<br />

That is for ever England. . . .” Biographer<br />

Paul Delany calls Brooke “the most famous<br />

British hero of the war.”<br />

Robert Graves (1895–1985):<br />

Though he was severely wounded in<br />

combat in 1916, Graves lived to be ninety.<br />

He served as a captain with the Royal<br />

Welch Fusiliers during World War I and<br />

befriended another member of the<br />

regiment, poet Siegfried Sassoon. Graves’s<br />

collection of war poems, Fairies and<br />

Fusiliers, helped establish his reputation as<br />

a literary figure after the war. The novel I,<br />

Claudius (1934) and the mythological<br />

study The White Goddess (1948) are his<br />

bestknown works. One of his sons was<br />

killed in World War II.<br />

Isaac Rosenberg (1890–1918):<br />

The son of Russian Lithuanian immigrants<br />

to England, Rosenberg enlisted in the<br />

British army in 1915, and because he was<br />

rather short, he was assigned to the<br />

Bantam Battalion, a regiment made up of<br />

volunteers who were below the regulation<br />

minimum height of 5 feet 2 inches. In the<br />

head, near Liverpool. <strong>Owen</strong> attended Birkenhead Institute<br />

until he was fourteen, when the family moved back to Shropshire,<br />

settling in the county seat at Shrewsbury. There, he<br />

attended Shrewsbury Technical School but failed in his efforts<br />

to win a scholarship to the University of London. He felt<br />

inclined toward religious work and accepted a position in<br />

which he received room and board in exchange for work with<br />

the vicar (a minister in charge of a church) of Dunsden in<br />

112 World War I: Biographies

last two years of his brief life, Rosenberg<br />

wrote several important versedramas<br />

about Old Testament subjects, including<br />

Moses and The Unicorn (about King Saul<br />

and his wife). Two important poems that<br />

he wrote while in military service are titled<br />

“Marching” and “Break of Day in the<br />

Trenches.” Critics regard Rosenberg’s<br />

“Dead Man’s Dump” (1917) as his finest<br />

“war” poem. Rosenberg was shot to death<br />

while on patrol duty during the Battle of<br />

the Somme on April 1, 1918.<br />

Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967):<br />

One of the poets who survived long after<br />

World War I, Sassoon befriended and<br />

encouraged such poets as Rupert Brooke,<br />

Robert Graves, and <strong>Wilfred</strong> <strong>Owen</strong>.<br />

Although he enlisted in the army and<br />

received awards for heroism, Sassoon<br />

became a pacifist and wrote an antiwar<br />

letter, “A Soldier’s Declaration,” that led<br />

some politicians to call for his courtmartial.<br />

With Robert Graves’s help, Sassoon was<br />

committed to a mental hospital instead,<br />

but he decided to return to combat so as<br />

not to betray his fellow soldiers. In 1919<br />

The War Poems of Siegfried Sassoon was<br />

published. The final poem celebrates the<br />

armistice of 1918 in these words: “. . .O,<br />

but Everyone / Was a bird; and the song<br />

was wordless; the singing will never be<br />

done.”<br />

Edward Thomas (1878–1917):<br />

Killed on Easter Sunday, 1917, during the<br />

Battle of Arras, the thirty-nine-year-old<br />

Thomas was older than most of the other<br />

World War I poets, and he had already<br />

established his literary career before the<br />

war. He was strongly influenced by the<br />

American poet Robert Frost (1874–1963).<br />

“Rain,” one of Thomas’s most important<br />

“war” poems, written in 1916, includes<br />

these lines: “Rain, midnight rain, and<br />

nothing but wild rain / On this bleak hut,<br />

and solitude, and me / Remembering<br />

again that I shall die. . .” His wife, Helen<br />

Thomas, also was a noted poet.<br />

Oxford. He left this position partly for health reasons and<br />

partly because he came to believe that the established church<br />

was failing in its duty to the poor. He returned to his family’s<br />

home briefly, then accepted a position teaching at the Berlitz<br />

School of Languages in Bordeaux, France. During this period,<br />

<strong>Owen</strong> started writing poetry. He admired the writings of the<br />

Romantic poets, like John Keats, and he became friends with<br />

the poet Laurent Tailhade, who was a fellow pacifist.<br />

<strong>Wilfred</strong> <strong>Owen</strong> 113

A sign in wartime France<br />

warning that antigas<br />

precautions should be taken<br />

when passing beyond this<br />

point. <strong>Wilfred</strong> <strong>Owen</strong>’s most<br />

famous poem, “Dulce et<br />

Decorum Est,” was inspired<br />

by his disgust at the use of<br />

poisonous gas. Reproduced by<br />

permission of Hulton<br />

Getty/Archive Photos, Inc.<br />

After World War I broke out, <strong>Owen</strong> returned to England<br />

and enlisted in the Artist’s Rifles, a special air service regiment.<br />

Commissioned a lieutenant in 1916, he was sent to<br />

fight in France with the Lancashire Fusiliers. It was while he<br />

was serving that he began to write his finest poetry, which<br />

described in graphic detail the agonies of his fellow soldiers.<br />

His most famous poem, “Dulce et Decorum Est,” was inspired<br />

by <strong>Owen</strong>’s disgust at the use of mustard gas (a poisonous gas<br />

that has irritating effects to the body) against his fellow soldiers;<br />

the poem’s ironic title is part of a Latin motto that means<br />

“Sweet and fitting it is to die for one’s country.” In <strong>Owen</strong>’s<br />

judgment, no one who had experienced the horrors of battle<br />

would proclaim such patriotic sentiments. In this excerpt from<br />

the poem, <strong>Owen</strong> addresses those who believe in the glory and<br />

heroism of war: “If in some smothering dreams you too could<br />

pace / Behind the wagon that we flung him in / My friend, you<br />

would not tell with such high zest / To children ardent for<br />

some desperate glory, / The old lie: Dulce et decorum est / Pro<br />

patria mori [Sweet and fitting it is to die for one’s country].”<br />

114 World War I: Biographies

Learning from Other Poets<br />

As his time in the service dragged on, <strong>Owen</strong> became<br />

increasingly bitter about the harsh and brutal conditions of the<br />

battlefield. In letters to his mother and in poems, he expressed<br />

a deep pessimism about the war, and he began to criticize the<br />

political leaders who were, in his mind, responsible for the carnage<br />

(killing). In June 1917, suffering from shell shock (a nervous<br />

breakdown due to combat conditions), <strong>Owen</strong> was admitted<br />

to Craiglockhart War Hospital for Nervous Disorders near<br />

Edinburgh, Scotland. He became editor of the hospital’s magazine,<br />

The Hydra, in which he published some of his poems as<br />

well as those of Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967), another British<br />

soldier at the hospital, who went on to become a well-known<br />

poet. <strong>Owen</strong> also taught at a local school and played in an amateur<br />

orchestra. This helped him recover from his nervous disorder,<br />

and he began to write some of his best poetry.<br />

Through Sassoon’s influence, <strong>Owen</strong> met many of the<br />

other prominent poets of the time. Among the literary figures<br />

who became his friends and mentors were Robert Graves<br />

(1895–1985), Robert Ross (1869–1918), and Charles Scott-<br />

Moncrieff (1889–1930). <strong>Owen</strong> felt that his association with<br />

these men gave him the tools he needed to succeed as a poet.<br />

He wrote a letter to his mother, quoted in the Norton Anthology<br />

of English Literature, in which he compared himself to a<br />

ship able to sail on its own, without the assistance of tugboats:<br />

“I am a poet’s poet. I am started. The tugs have left me. I feel<br />

a great swelling of the opening sea taking my galleon [large<br />

sailing ship].”<br />

Return to the Battlefield<br />

Despite his pacifist inclinations, <strong>Owen</strong> resolved to go<br />

back to the battlefield out of loyalty to his comrades and in<br />

order to write more authentically about the experiences of battle.<br />

On December 31, 1917, he wrote in his journal (quoted in<br />

the Norton Anthology of English Literature) about the terror he<br />

had once seen in his comrades’ faces: “It will never be painted,<br />

and no actor will ever seize it. And to describe it, I think I must<br />

go back and be with them.”<br />

By August 1918, <strong>Owen</strong> had recovered from his illness<br />

well enough to return to France. He won a Military Cross for<br />

<strong>Wilfred</strong> <strong>Owen</strong> 115

<strong>Wilfred</strong> <strong>Owen</strong>’s poems<br />

described the deplorable<br />

conditions that soldiers had<br />

to face on the battlefield,<br />

like this American soldier<br />

standing guard during a<br />

German gas attack in<br />

France. Reproduced by<br />

permission of Hulton<br />

Getty/Archive Photos, Inc.<br />

bravery when he helped lead his company to safety during a<br />

battle. On November 4, while leading a group of soldiers across<br />

the Sambre Canal, <strong>Owen</strong> was killed in a hail of machinegun<br />

fire. He died four months short of his twenty-sixth birthday—<br />

and exactly one week before the armistice (peace treaty) of<br />

November 11 brought World War I to an end. . A few months<br />

before his death, <strong>Owen</strong> had written a preface for an edition of<br />

his poetry that he hoped to have published. In 1985, an<br />

excerpt from this preface—”My subject is War, and the pity of<br />

War. The poetry is in the pity. . .”—was carved into a monument<br />

that memorializes sixteen World War I poets in the Poets’<br />

Corner of Westminster Abbey in London.<br />

Siegfried Sassoon knew the quality of <strong>Owen</strong>’s verses<br />

and arranged to have twenty-three of <strong>Owen</strong>’s poems published.<br />

The collection, titled Poems, appeared in 1920; it was<br />

edited by Edith Sitwell, a member of a prominent literary family<br />

in England. Her brother, Osbert Sitwell, had been a friend<br />

of <strong>Owen</strong> and Sassoon. In 1931, an expanded edition with<br />

116 World War I: Biographies

twenty-nine poems was published, together with an introduction<br />

by Edmund Blunden, another notable British poet who<br />

had served in World War I. <strong>Owen</strong>’s work has continued to<br />

inspire later generations of poets, such as Cecil DayLewis who<br />

in 1964 edited The Collected Poems of <strong>Wilfred</strong> <strong>Owen</strong>, which<br />

included seventy-nine poems.<br />

For More Information<br />

Books<br />

Abrams, M.H., et al, editors. Norton Anthology of English Literature. Volume<br />

2; 7th edition. New York: Norton, 2000.<br />

Delany, Paul. Rupert Brooke and the Ordeal of Youth. New York: Free Press,<br />

1987.<br />

<strong>Owen</strong>, <strong>Wilfred</strong>. Collected Letters. London and New York: Oxford University<br />

Press, 1967.<br />

<strong>Owen</strong>, <strong>Wilfred</strong>. War Poems and Others. London: Chatto and Windus, 1973.<br />

Stallworthy, Jon. <strong>Wilfred</strong> <strong>Owen</strong>: A Biography. Oxford: Oxford University<br />

Press, 1975.<br />

Sound Recordings<br />

Britten, Benjamin. War Requiem (op. 66), 1962; recorded by Deutsche<br />

Grammophon, Hamburg, 1993.<br />

Films<br />

War Requiem. Directed by Derek Jerman. Mystic Fire Video, 1988. Videocassette.<br />

Web sites<br />

“The Poems of <strong>Wilfred</strong> <strong>Owen</strong>.” [Online] http://www.pitt.edu/~novosel/<br />

owen.html (accessed April 2001).<br />

“The War Poets Collection.” [Online] http://www.napier.ac.uk/depts/<br />

library/craigcon/warpoets/warphome.htm (accessed April 2001).<br />

“The <strong>Wilfred</strong> <strong>Owen</strong> Association.” [Online] http://www.191418.co.uk/<br />

owen (accessed April 2001).<br />

“WOMDA: The <strong>Wilfred</strong> <strong>Owen</strong> Multimedia Digital Archive.” [Online]<br />

http://www.hcu.ox.ac.uk/jtap/ (accessed April 2001).<br />

<strong>Wilfred</strong> <strong>Owen</strong> 117