Volume 33 Number 3 June 2006 - International Clarinet Association

Volume 33 Number 3 June 2006 - International Clarinet Association

Volume 33 Number 3 June 2006 - International Clarinet Association

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Volume</strong> <strong>33</strong> <strong>Number</strong> 3<br />

<strong>June</strong> <strong>2006</strong>

<strong>Volume</strong> <strong>33</strong>, <strong>Number</strong> 3 <strong>June</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

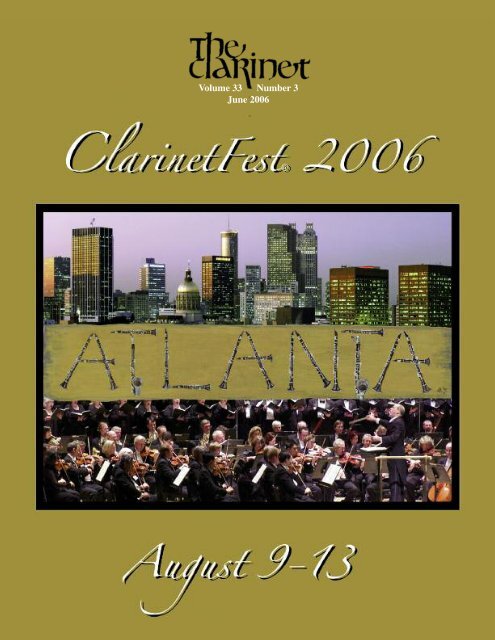

ABOUT THE COVER…<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong>Fest® <strong>2006</strong> poster<br />

INDEX OF ADVERTISERS<br />

Alea Publishing & Recording....................................24<br />

Alexander’s Wind Instrument Center........................31<br />

Altieri Instrument Bags .............................................79<br />

Ben Armato .................................................................7<br />

Backun Musical Services....................................43, 87,<br />

Inside Back Cover<br />

Charles Bay ...............................................................20<br />

Behn Mouthpieces <strong>International</strong>................................13<br />

Kristin Bertrand Woodwind Repair...........................23<br />

Bois Ligatures............................................................79<br />

Robert Borbeck..........................................................61<br />

Brannen Woodwinds .................................................<strong>33</strong><br />

Buffet Crampon USA, Inc...............Inside Front Cover<br />

CASS ...........................................................................9<br />

Crystal Records .........................................................23<br />

J. D’Addario — Rico Reeds........................................8<br />

The Davie Cane Company.........................................27<br />

Expert Woodwind Service, Inc..................................16<br />

Fleming Instrument Repair 79Gold Branch Music, Inc.<br />

27<br />

LampCraft..................................................................73<br />

Last Resort Music......................................................37<br />

Leblanc (Conn-Selmer) ...............................................2<br />

Lisa’s <strong>Clarinet</strong> Shop ..................................................41<br />

Lomax Classic Mouthpieces......................................57<br />

Luyben Music Co. .....................................................21<br />

Muncy Winds ............................................................24<br />

Naylor’s Custom Wind Repair ..................................83<br />

Olivieri Reeds............................................................41<br />

Ongaku Records, Inc. ..................................................5<br />

Orsi & Weir ...............................................................89<br />

Sean Osborn...............................................................61<br />

Patricola Fratelli SNS ................................................30<br />

Pomarico....................................................................84<br />

Bernard Portnoy.........................................................<strong>33</strong><br />

Quodlibet. Inc. ...........................................................73<br />

Rast Music ...................................................................5<br />

Redwine Jazz .........................................................7, 73<br />

Reeds Australia..........................................................39<br />

L. Rossi......................................................................50<br />

Rutgers University, Mason Gross<br />

School of the Arts..................................................83<br />

Sayre Woodwinds......................................................27<br />

Selmer Paris (Conn-Selmer) .........Outside Back Cover<br />

Tap Music Sales ........................................................12<br />

TYRO by Mitchell Lurie ...........................................17<br />

University of Denver Lamont School of Music ........88<br />

University of Georgia School of Music.......................4<br />

University of Redlands ..............................................25<br />

University of South Carolina<br />

School of Music.....................................................92<br />

Van Cott Information Services..................................18<br />

Vandoren ...................................................................49<br />

Wichita Band Instrument Co. ....................................77<br />

Woodwindiana, Inc....................................................31<br />

Working the Single Reed: A Tutorial........................77<br />

Yamaha Corporation of America ..............................91<br />

Features<br />

THE CLARINET TEACHING OF KEITH STEIN — PART 15: TONE QUALITY<br />

by David Pino ..........................................................................................................................................................32<br />

THE ECLECTIC TRIO: RECOMMENDED TRIOS AND DUOS FOR FLUTE,<br />

CLARINET AND SAXOPHONE by Kennen White, Joanna Cowan White and John Nichol....................................35<br />

EARLY CLARINET PEDAGOGY FOR MODERN PERFORMERS, PART III:<br />

THOUGHTS ON ARTICULATION by Luc Jackman........................................................................................38<br />

WEBER’S CLARINET CHAMBER MUSIC WITHOUT BAERMANN by Joachim Veit..........................40<br />

THE MOVIES OF BENNY GOODMAN — A PICTORIAL RETROSPECTIVE, TAKE 3<br />

by James Gillespie ....................................................................................................................................................44<br />

USE OF THE CLARINET BY THE MORAVIAN SOCIETIES OF EARLY AMERICA<br />

by Jesse Krebs..........................................................................................................................................................48<br />

LAUDATE MARTINO TRIBUTES AFTER DONALD MARTINO (1931–2005)<br />

by Bruce M. Creditor.................................................................................................................................................55<br />

INTERNATIONAL CLARINET ASSOCIATION ATLANTA CLARINETFEST® <strong>2006</strong>:<br />

AUGUST 9–13 .....................................................................................................................................................58<br />

DONALD E. McGINNIS, AN AMERICAN SUCCESS STORY by Jaime Titus.............................................62<br />

HYACINTHE KLOSÉ (1808–1880): HIS WORKS FOR CLARINET by Jean-Marie Paul...........................66<br />

MEDLEY WITH DIGRESSIONS by Henry Gulick ...........................................................................................72<br />

HOW TO HELP YOUR STUDENTS BUILD A CAREER IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY<br />

by Lisa Argiris..........................................................................................................................................................74<br />

TONY SCOTT, PART II: THE LATER YEARS by Thomas W. Jacobsen........................................................75<br />

AN INTERVIEW WITH FRANSISCO GOMILA by Ian Jewel......................................................................78<br />

Departments<br />

LETTERS...............................................................................................................................................................5<br />

TEACHING CLARINET by Michael Webster.......................................................................................................6<br />

CLARINOTES....................................................................................................................................................12<br />

AUDIO NOTES by William Nichols ......................................................................................................................14<br />

CONFERENCES & WORKSHOPS.................................................................................................................18<br />

HISTORICALLY SPEAKING… by Deborah Check Reeves...............................................................................22<br />

LETTER FROM THE U.K. by Paul Harris .......................................................................................................24<br />

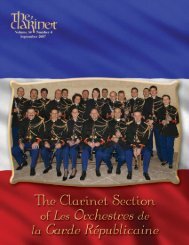

CLARINETISTS IN UNIFORM by Staff Sergeant Diana Cassar-Uhl..................................................................26<br />

INDUSTRY PROFILES — Phil Rovner of Rovner Products, Timonium, Maryland<br />

by Edward Palanker .................................................................................................................................................28<br />

REVIEWS ...........................................................................................................................................................80<br />

RECITALS AND CONCERTS.........................................................................................................................88<br />

THE PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE by Lee Livengood ...........................................................................................90<br />

<strong>June</strong> <strong>2006</strong> Page 1

INTERNATIONAL CLARINET ASSOCIATION<br />

Acting President: Lee Livengood, 490 Northmont Way, Salt Lake City, UT 84103, E-mail: <br />

Past President: Robert Walzel, School of Music, University of Utah, 204 David P. Gardner Hall, 1375 East Presidents<br />

Circle, Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0030, 801/273-0805 (home), 801/581-6765 (office), 801/581-5683 (fax), E-mail:<br />

<br />

Secretary: Kristina Belisle, School of Music, University of Akron, Akron, OH 44325-1002, <strong>33</strong>0/972-8404 (office),<br />

<strong>33</strong>0/972-6409 (fax), E-mail: <br />

Treasurer: Diane Barger, School of Music, University of Nebraska–Lincoln, 120 Westbook Music Building, Lincoln, NE<br />

68588-0100, 402/472-0582 (office), 402/472-8962 (fax), E-mail: <br />

Executive Director: So Rhee, P.O. Box 1310, Lyons, CO 80540, 801/867-4<strong>33</strong>6 (phone), 212/457-6124 (fax), E-mail:<br />

<br />

Editor/Publisher: James Gillespie, College of Music, University of North Texas, P.O. Box 311367, Denton, TX 76203-1367,<br />

940/565-4096 (office), 940/565-2002 (fax), E-mail: <br />

Editorial Associates: Lee Gibson, 1226 Kendolph, Denton, TX 76205; Himie Voxman, 821 N. Linn, Iowa City, IA 52245<br />

Contributing Editor: Joan Porter, 400 West 43rd, Apt. 41L, New York, NY 10036<br />

Editorial Staff: Joseph Messenger (Editor of Reviews), Department of Music, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011,<br />

515/294-3143, E-mail: ; William Nichols (Audio Review Editor), 111 Steeplechase Circle,<br />

West Monroe, LA 71291, 318/396-8299, E-mail: ; Tsuneya Hirai, 11-9 Oidecho,<br />

Nishinomiya, 662-0036 Japan; Kalmen Opperman, 17 West 67th Street, #1 D/S, New York, NY 10023; Heston L.<br />

Wilson, M.D., 1155 Akron Street, San Diego, CA 92106, E-mail: ; Michael Webster,<br />

Shepherd School of Music, Rice University, P.O. Box 1892, Houston, TX 77251-1892, 713/838-0420 (home),<br />

713/838-0078 (fax), E-mail: ; Bruce Creditor, 11 Fisher Road, Sharon, MA 02067, E-mail:<br />

; Thomas W. Jacobsen, 3970 Laurel Street, New Orleans, LA 70115, E-mail: ; Jean-Marie Paul, Vandoren, 56 rue Lepic, F-75018 Paris, France, (<strong>33</strong>) 1 53 41 83 08 (phone),<br />

(<strong>33</strong>) 53 41 83 02 (fax), E-mail: ; Deborah Check Reeves, Curator of Education, National<br />

Music Museum, University of South Dakota, 414 E. Clark St., Vermillion, SD 57069; phone: 605/ 677-5306; fax:<br />

605/677-6995; Museum Web site: ; Personal Web site: ;<br />

Paul Harris, 15, Mallard Drive, Buckingham, Bucks. MK18 1GJ, U.K.; E-mail: ;<br />

Diana Cassar-Uhl, 26 Rose Hill Park, Cornwall, NY 12518<br />

I.C.A. Research Center: SCPA, Performing Arts Library, University of Maryland, 2511 Clarice Smith Performing<br />

Arts Center, College Park, MD 20742-1630<br />

Research Coordinator and Library Liaison: Keith Koons, Music Department, University of Central Florida,<br />

P.O. Box 161354, Orlando, FL 32816-1354, 407/823-5116 (phone), E-mail: <br />

Webmaster: Kevin Jocius, Headed North, Inc. Web Design, 847/742-4730 (phone), <br />

Historian: Alan Stanek, 1352 East Lewis Street, Pocatello, ID 83201-4865, 208/232-1<strong>33</strong>8 (phone), 208/282-4884 (fax),<br />

E-mail:<br />

<strong>International</strong> Liaisons:<br />

Australasia: Floyd Williams, 27 Airlie Rd, Pullenvale, Qld, Australia, (61)7 <strong>33</strong>74 2392 (phone), E-mail <br />

Europe/Mediterranean: Guido Six, Artanstraat 3, BE-8670 Oostduinkerke, Belgium, (32) 58 52 <strong>33</strong> 94 (home), (32) 59 70 70<br />

08 (office), (32) 58 51 02 94 (home fax), (32) 59 51 82 19 (office fax), E-mail: <br />

North America: Luan Mueller, 275 Old Camp Church Road, Carrollton, GA 30117, 678/796-2414 (cell), E-mail: <br />

South America: Marino Calva, Ejido Xalpa # 30 Col. Culhuacan, Mexico D.F. 04420 Coyoacan, (55) 56 95 42 10<br />

(phone/fax), (55) 91 95 85 10 (cell), E-mail: <br />

National Chairpersons:<br />

Argentina: Mariano Frogioni, Bauness 2760 4to. B, CP: 1431, Capital Federal, Argentina<br />

Armenia: Alexandr G. Manukyan, Aigestan str. 6 h. 34,Yerevan 375070, Armenia, E-mail: <br />

Australia: Floyd Williams, Queensland Conservatorium, P. O. Box 3428, Brisbane 4001, Australia; 61/7 3875 6235 (office);<br />

61/7 <strong>33</strong>74 2392 (home); 61/7<strong>33</strong>740347 (fax); E-mail: <br />

Austria: Alfred Prinz, 3712 Tamarron Dr., Bloomington, Indiana 47408, U.S.A. 812/<strong>33</strong>4-2226<br />

Belgium: Guido Six, Artanstraat 3, B-8670 Oostduinkerke, Belgium, 32/58 52 <strong>33</strong> 94 (home), 32 59 70 70 08 (office),<br />

Fax 32 58 51 02 94 (home), 32 59 51 82 19 (office), E-mail:<br />

Brazil: Ricardo Dourado Freire, SHIS QI 17 conj. 11 casa 02, 71.645-110 Brasília-DF, Brazil, 5561/248-1436 (phone),<br />

5561/248-2869 (fax), E-mail: <br />

Canada: Peter Spriggs, The <strong>Clarinet</strong> Center, P.O. Box 159, Penticton, British Columbia V2A 6J9, Canada, Phone/Fax<br />

250/497-8200, E-mail: <br />

Eastern Canada: Stan Fisher, School of Music, Acadia University, Wolfville, Nova Scotia B0P 1XO, Canada<br />

Central Canada: Connie Gitlin, School of Music, University of Manitoba, 65 Dafoe Road, Winnipeg, MB, R3T 2N2, Phone<br />

204/797-3220, E-mail: <br />

Western Canada: Gerald N. King, School of Music, University of Victoria, Box 1700 STN CSC, Victoria, British Columbia V8W<br />

2Y2, Canada, Phone 250/721-7889, Fax 250/721-6597, E-mail: <br />

Caribbean: Kathleen Jones, Torrimar, Calle Toledo 14-1, Guaynabo, PR 00966-3105, Phone 787/782-4963,<br />

E-mail: <br />

Chile: Luis Rossi, Coquimbo 10<strong>33</strong> #1, Santiago centro, Chile, (phone/fax) 562/222-0162, E-mail: <br />

Costa Rica: Alvaro D. Guevara-Duarte, 300 M. Este Fabrica de Hielo, Santa Cruz-Guanacaste, Costa Rica, Central America,<br />

E-mail: <br />

Czech Republic: Stepán Koutník, K haji 375/15 165 00 Praha 6, Czech Republic, E-mail: <br />

Denmark: Jørn Nielsen, Kirkevaenget 10, DK-2500 Valby, Denmark, 45-36 16 69 61 (phone),<br />

E-mail: <br />

Finland: Anna-Maija Joensuu, Finish <strong>Clarinet</strong> Society, Karipekka Eskelinen, Iso Roobertinkatu 42A 16, 00120 Finland,<br />

358-(0)500-446943 (phone), E-mail: <br />

France: Guy Deplus, 37 Square St. Charles, Paris, France 75012, phone <strong>33</strong> (0) 143406540<br />

Germany: Ulrich Mehlhart, Dornholzhauser Str. 20, D-61440 Oberursel, Germany, <br />

Great Britain: David Campbell, 83, Woodwarde Road, London SE22 8UL, England, 44 (0)20 8693 5696 (phone/fax),<br />

E-mail: <br />

Greece: Paula Smith Diamandis, S. Petroula 5, Thermi 57001, Thessaloniki, Greece, E-mail: <br />

Hong Kong: Andrew Simon, 14B Ying Pont Building, 69-71A Peel Street, Hong Kong (011) 852 2987 9603 (phone),<br />

E-mail , <br />

Hungary: József Balogh, Bécsi u. 88/90.1/31, H-1034 Budapest, Hungary, 36 1 388 6689 (phone/fax),<br />

E-mail:, <br />

Iceland: Kjartan ‘Oskarsson, Tungata 47, IS-101, Reykjavik, Iceland, 354 552 9612 (phone), E-mail: <br />

Ireland: Tim Hanafin, Orchestral Studies Dept., DIT, Conservatory of Music, Chatham Row, Dublin 2, Ireland,<br />

353 1 4023577 (fax), 353 1 4023599 (home phone), E-mail: <br />

Israel: Eva Wasserman-Margolis, Weizman 6, Apt. 3, Givatayim, Israel 53236, E-mail: <br />

Italy: Luigi Magistrelli, Via Buonarroti 6, 20010 S. Stefano Ticino (Mi), Italy, 39/(0) 2 97 27 01 45 (phone/fax),<br />

E-mail: <br />

Japan: Koichi Hamanaka, Rm 575 9-1-7 Akasaka Minatoku, Tokyo 107-0052 Japan, 81-3-3475-2844 (phone), 81-3-3475-6417<br />

(fax), Web site: , E-mail: <br />

Korea: Im Soo Lee, Hanshin 2nd Apt., 108-302, Chamwondong Suhchoku, Seoul, Korea. (02) 5<strong>33</strong>-6952 (phone),<br />

(02) 3476-6952 (fax), E-mail: <br />

Luxembourg: Marcel Lallemang, 11 Rue Michelshof, L-6251 Scheidgen, Luxembourg, E-mail: <br />

Mexico: Luis Humberto Ramos, Calz. Guadalupe I. Ramire No. 505-401 Col. San Bernadino, Xochimilco, Mexico D.F.,<br />

16030. 6768709 (fax), E-mail: <br />

Netherlands: Nancy Wierdsma-Braithwaite, Arie van de Heuvelstraat 10, 3981 CV, Bunnik, Netherlands, E-mail:<br />

<br />

New Zealand: Andrew Uren, 26 Appleyard Crescent, Meadowbank, Auckland 5, New Zealand,<br />

64 9 521 2663 (phone and fax).<br />

Norway: Håkon Stødle, Fogd Dreyersgt. 21, 9008 Tromsø, Norway 47/77 68 63 76 (home phone), 47/77 66 05 51 (phone,<br />

Tromsø College), 47/77 61 88 99 (fax, Tromsø College), E-mail: <br />

People’s Republic of China: Guang Ri Jin, Music Department, Central National University, No. 27 Bai Shi Qiao Road,<br />

Haidian District, Beijing, People’s Republic of China, 86/10-6893-3290 (phone)<br />

Peru: Ruben Valenzuela Alejo, Av. Alejandro Bertello 1092, Lima, Peru 01, 564-0350 or 564-0360 (phone),<br />

(51-1) 564-4123 (fax), E-mail: <br />

Poland: Krzysztof Klima, os. Wysokie 10/28, 31-819 Krakow, Poland. 48 12 648 08 82 (phone), 48 12 648 08 82 (fax),<br />

E-mail: <br />

Portugal: António Saiote, Rua 66, N. 125, 2 Dto., 4500 Espinho, Portugal, 351-2-731 0389 (phone)<br />

Slovenia: Jurij Jenko, C. Na Svetje 56 A, 61215 Medvode, Slovenia. Phone 386 61 612 477<br />

South Africa: Edouard L. Miasnikov, P.O. Box 249, Auckland Park, <strong>2006</strong>, Johannesburg, South Africa,<br />

(011) 476-6652 (phone/fax)<br />

Spain: vacant<br />

Sweden: Kjell-Inge Stevensson, Erikssund, S-193 00 Sigtuna, Sweden<br />

Switzerland: Andreas Ramseier, Alter Markt 6, CH-3400 Burgdorf, Switzerland<br />

Taiwan: Chien-Ming, 3F, <strong>33</strong>, Lane 120, Hsin-Min Street, Tamsui, Taipei, Taiwan 25103<br />

Thailand: Peter Goldberg, 105/7 Soi Suparat, Paholyotin 14, Phyathai, Bangkok 10400 Thailand<br />

662/616-8<strong>33</strong>2 (phone) or 662/271-4256 (fax), E-mail: <br />

Uruguay: Horst G. Prentki, José Martí 3292 / 701, Montevideo, Uruguay 11300, 00598-2-709 32 01 (phone)<br />

Venezuela: Victor Salamanques, Calle Bonpland, Res. Los Arboles, Torrec Apt. C-14D, Colinas de Bello Yonte Caracas<br />

1050, Venezuela, E-mail: <br />

H O N O R A R Y M E M B E R S<br />

Betty Brockett (1936–2003)<br />

Jack Brymer (1915–2003)<br />

Guy Deplus, Paris, France<br />

Stanley Drucker, New York, New York<br />

F. Gerard Errante, Norfolk, Virginia<br />

Lee Gibson, Denton, Texas<br />

James Gillespie, Denton, Texas<br />

Paul Harvey, Twickenham, Middlesex, U.K.<br />

Stanley Hasty, Rochester, New York<br />

Ramon Kireilis, Denver, Colorado<br />

Karl Leister, Berlin, Germany<br />

Mitchell Lurie, Los Angeles, California<br />

Alfred Prinz, Bloomington, Indiana<br />

Harry Rubin, York, Pennsylvania<br />

James Sauers (1921–1988)<br />

William O. Smith, Seattle, Washington<br />

Ralph Strouf (1926–2002)<br />

Himie Voxman, Iowa City, Iowa<br />

George Waln (1904–1999)<br />

David Weber (1914-<strong>2006</strong>)<br />

Pamela Weston, Hothfield, Kent, U.K.<br />

Commercial Advertising / General Advertising Rates<br />

RATES & SPECIFICATIONS<br />

The <strong>Clarinet</strong> is published four times a year and contains at least 48 pages printed offset on 70<br />

lb. gloss stock. Trim size is approximately 8 1/4" x 11". All pages are printed with black ink,<br />

with 4,000 to 4,500 copies printed per issue.<br />

DEADLINES FOR ARTICLES, ANNOUNCEMENTS, RECITAL<br />

PROGRAMS, ADVERTISEMENTS, ETC.<br />

Sept. 1 for Dec. issue • Dec. 1 for Mar. issue • Mar. 1 for <strong>June</strong> issue • <strong>June</strong> 1 for Sept. issue<br />

—ADVERTISING RATES —<br />

Size Picas Inches Single Issue (B/W) Color**<br />

Outside Cover* 46x60 7-5/8x10 $1,000<br />

Inside Cover* 46x60 7-5/8x10 $560 $ 855<br />

Full Page 46x60 7-5/8x10 $420 $ 690<br />

2/3 Vertical 30x60 5x10 $320 $ 550<br />

1/2 Horizontal 46x29 7-5/8x4-3/4 $240 $ 470<br />

1/3 Vertical 14x60 2-3/8x10 $200 $ <strong>33</strong>0<br />

1/3 Square 30x29 5x4-3/4 $200 $ <strong>33</strong>0<br />

1/6 Horizontal 30x13-1/2 5x2-3/8 $120 $ 230<br />

1/6 Vertical 14x29 2-3/8x4-3/4 $120 $ 230<br />

**First request honored.<br />

**A high-quality color proof, which demonstrates approved color, must accompany all color submissions. If not<br />

provided, a color proof will be created at additional cost to advertiser.<br />

NOTE: Line screen values for the magazine are 150 for black & white ads and 175 for color. If the poor quality of<br />

any ad submitted requires that it be re-typeset, additional charges may be incurred.<br />

All new ads must be submitted in an electronic format. For more information concerning this procedure,<br />

contact Executive Director So Rhee.<br />

THE INTERNATIONAL CLARINET ASSOCIATION<br />

MEMBERSHIP FEES<br />

Student: $25 (U.S. dollars)/one year; $45 (U.S. dollars)/two years<br />

Regular: $50 (U.S. dollars)/one year; $95 (U.S. dollars)/two years<br />

Institutional: $50 (U.S. dollars)/one year; $95 (U.S. dollars)/two years<br />

Payment must be made by check, money order, Visa, MasterCard, American Express, or<br />

Discover. Make checks payable to the <strong>International</strong> <strong>Clarinet</strong> <strong>Association</strong> in U.S. dollars.<br />

Please use <strong>International</strong> Money Order or check drawn on U.S. bank only. Send payment to:<br />

The <strong>International</strong> <strong>Clarinet</strong> <strong>Association</strong>, So Rhee, P.O. Box 1310, Lyons, CO 80540 USA.<br />

© Copyright <strong>2006</strong>, INTERNATIONAL CLARINET ASSOCIATION<br />

ISSN 0361-5553 All Rights Reserved<br />

Published quarterly by the INTERNATIONAL CLARINET ASSOCIATION<br />

Designed and printed by BUCHANAN VISUAL COMMUNICATIONS - Dallas, Texas U.S.A.<br />

Views expressed by the writers and reviewers in The <strong>Clarinet</strong> are not necessarily those of the staff of the journal or of the <strong>International</strong> <strong>Clarinet</strong> <strong>Association</strong><br />

<strong>June</strong> <strong>2006</strong> Page 3

(Letters intended for publication in The<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> should be addressed to James<br />

Gillespie, Editor, “Letters,” The <strong>Clarinet</strong>,<br />

College of Music, University of North<br />

Texas, Denton, Texas 76203-1367 or via<br />

e-mail: .<br />

Letters may be edited for purposes of clarity<br />

and space.)<br />

Editor:<br />

In response to the English reader who<br />

exoriated The <strong>Clarinet</strong> for “obituary material”<br />

that was “insulting” to Artie Shaw, I<br />

must say that like so much criticism, his<br />

comments are really a lack of understanding.<br />

This delightful process of understanding<br />

should not be denied this reader who,<br />

by his admission, does not even subscribe<br />

to The <strong>Clarinet</strong>. The articles in the March<br />

2005 issue are not labeled as an obituary,<br />

but rather as a tribute and remembrances.<br />

Mr. Shaw retired from music more than 50<br />

years ago, so it would seem that he did not<br />

regard the clarinet as the most important<br />

aspect of his life. Anyone who has read<br />

his book, The Trouble With Cinderella. An<br />

Outline of Identity, knows that he viewed<br />

music as only one part of life, albeit a vital<br />

part. The personal tributes offer invaluable<br />

insights into his character and philosophy.<br />

The articles in The <strong>Clarinet</strong> were published<br />

on short notice and certainly allow<br />

a better understanding of Artie Shaw musically.<br />

Perhaps instead of dashing off a<br />

querulous letter, the reader could submit<br />

an article about Shaw and contribute<br />

something constructive, and also allow<br />

us to share his erudition. The <strong>Clarinet</strong> is<br />

far better than any other publication<br />

about the instrument, in my opinion, and<br />

it is to be commended.<br />

Sincerely,<br />

John R. Snyder<br />

Knoxville, TN<br />

CLARINETFEST® <strong>2006</strong> ONLINE REGISTRATION<br />

Registration for <strong>Clarinet</strong>Fest® <strong>2006</strong> in Atlanta is available online. Consult the I.C.A.<br />

Web site for details and information.<br />

<strong>June</strong> <strong>2006</strong> Page 5

ut you have no idea where you might be<br />

when you exit.<br />

Nobody utilized the diminished seventh<br />

chord better than J.S. Bach. Example 15<br />

has two modulatory diminished seventh<br />

chords, in mm. 6 and 8. By m. 5, we have<br />

modulated from the tonic key of G major<br />

to the dominant, D major. In each case, a<br />

raised fourth scale step becomes the leading<br />

tone of a new minor key a fifth higher,<br />

namely A minor and E minor. In m. 10,<br />

the sixth scale step is raised to become the<br />

leading tone, but this time as part of a<br />

dominant seventh in D major.<br />

by Michael Webster<br />

Michael Webster<br />

SEVENTH HEAVEN,<br />

THE JOURNEY CONCLUDED<br />

Thirty-third in a series of articles using<br />

excerpts from a clarinet method in progress<br />

by the Professor of <strong>Clarinet</strong> and<br />

Ensembles at Rice University’s Shepherd<br />

School of Music<br />

This is a continuation of “Seventh Heaven,”<br />

The <strong>Clarinet</strong> (March <strong>2006</strong>)<br />

In our March issue, “Seventh Heaven”<br />

left us dangling on a diminished seventh<br />

chord, with all of its power, ambiguity,<br />

and possibility. Because of its<br />

symmetry (all minor thirds, one spelled as<br />

an augmented second), the diminished<br />

seventh chord is an easy and versatile modulatory<br />

aid. Like a revolving door for the<br />

Keystone Kops, it can be entered at will,<br />

Page 6<br />

Should the student be keeping track of<br />

these modulations Absolutely! In working<br />

with very advanced college-aged students,<br />

I have found that this is one aspect<br />

of their musical education that has often<br />

been neglected. All players of melody<br />

instruments should learn to think vertically,<br />

and the music of J.S. Bach, and of<br />

Praeludium XV in particular, is perfect for<br />

this purpose. A moment’s glance shows<br />

that it uses a standard exercise pattern that<br />

appears in “Promise Her Anything, But<br />

THE CLARINET<br />

Give Her Arpeggios” (The <strong>Clarinet</strong>, September,<br />

2005) as Example 5. Having practiced<br />

the pattern in the appropriate keys,<br />

players then access the chords from their<br />

memory banks (brain and fingers) as they<br />

are applied like this:<br />

m. 1 Key of G major<br />

I (GM)<br />

IV (CM)<br />

m. 2 VII (F ♯ d)<br />

I (GM)

m. 3 Modulation to D Major<br />

V of V (AM)<br />

V/I (DM)<br />

This brings us to the downbeat of m. 4,<br />

where a second pattern begins, sharing the<br />

melodic duties with the first pattern for the<br />

remainder of this short but beautifully constructed<br />

piece.<br />

The tonic pedal point in the lower voice<br />

of mm. 1 & 2 does not change the harmonic<br />

thinking of the top voice, nor does the<br />

fact that it adds a seventh to the A major<br />

triad in m. 3. Part of this harmonic ear<br />

training is to learn how VII, V, VII 7 and V 7<br />

are interlocking variations of each other,<br />

all leading strongly to the tonic. The upper<br />

voice plays V, but hears V 7 in m. 3.<br />

The new pattern in mm. 4 and 5 does<br />

not fall into any of our pre-practiced routines<br />

and can be viewed as an upward and<br />

downward scale in D major, interrupted by<br />

a C ♯ –D pedal point. The harmonic background<br />

is obscured by its scalar nature, but<br />

can be analyzed as:<br />

m. 4 Key of D major<br />

II 7 (incomplete Em 7 )<br />

V 7 (AMm 7 )<br />

m. 5 I (DM)<br />

<strong>June</strong> <strong>2006</strong> Page 7

It is not necessary to recognize the II 7<br />

chord, but it is necessary to hear the second<br />

half of m. 4 as an elaborated V 7 resolving<br />

to I in D major.<br />

Recognizing a new leading tone is the<br />

most valuable skill in this kind of harmonic<br />

reading. The diminished seventh chords<br />

are presented in Example 14 of “Seventh<br />

Heaven” (The <strong>Clarinet</strong>, March, <strong>2006</strong>) as<br />

VII 7 in minor keys because that is their<br />

most common function. As soon as we see<br />

the diminished seventh chord on G ♯ in m. 6<br />

we read G ♯ as the leading tone and the<br />

chord as VII 7 in A minor; the D ♯ diminished<br />

seventh chord in m. 8 serves E minor<br />

the same way. The fluidity of VII 7 and V 7<br />

is demonstrated by the intrusion of this<br />

most fleeting of dominants: an E in m. 6<br />

and a B in m. 8.<br />

It is slightly harder to identify C ♯ in m.<br />

10 as a leading tone, but experience will<br />

help to identify such situations more fluently.<br />

D major is the key and the dominant<br />

chord can be seen (and heard) in both voices<br />

on the four strong beats in the measure.<br />

The top voice finishes with a complete<br />

dominant seventh chord on the last beat<br />

starting a sequence that is very rich in seventh<br />

chords:<br />

m. 11 Key of D major<br />

I (DM)<br />

I 7 or V 7 of IV (DMm 7 )<br />

IV (GM)<br />

V 7 (AMm 7 )<br />

m. 12 I 7 (DM 7 )<br />

IV 7 (GM 7 )<br />

II 7 (Em 7 )<br />

V 7 (AMm 7 )<br />

m. 13 Modulation to G Major<br />

I 7 /V 7 (DMm 7 )<br />

I 7 or V 7 of IV (GMm 7 )<br />

m. 14 IV 7 (CM 7 )<br />

II 7 or V 7 of V (AMm 7 )<br />

m. 15 V 7 (DM 7 ; DMm 7 )<br />

m. 16 I 7 or V 7 of IV (GMm 7 )<br />

In the second half of m. 16 the fun really<br />

begins. From here to the end it would<br />

be possible to analyze every eighth-note<br />

beat in G major, but that wouldn’t be descriptive<br />

enough. The bottom line can (and<br />

should) be read as a series of seventh<br />

chords: DMm 7 , CM 7 , Bm 7 , Am 7 , GM 7 ,<br />

F ♯ dm 7 . The top line could be read simply<br />

as triads: CM, DM, Bm, CM, Am, Bm,<br />

GM, AM, etc. But it is more fun and more<br />

consistent with what is heard to read them<br />

as overlapping seventh chords:<br />

C-E-G-A = Am 7 ; A-F ♯ -D-B = Bm 7 ;<br />

B-D-F ♯ -G = GM 7 ; G-E-C-A = Am 7 , etc.<br />

Finally, if you consider the four notes<br />

of each seventh chord in the bottom voice<br />

together with the six notes above it, you<br />

have a series of ninth chords that would<br />

make Dave Brubeck envious. In practical<br />

terms, the upper voice will have been “preprogrammed”<br />

in Example 6 of “Seventh<br />

Heaven,” resulting in fluent reading and<br />

quick learning.<br />

The seventh chords in Praeludium XI<br />

(see Example 16) are only slightly more<br />

disguised than those in Praeludium XV,<br />

but they are even more persistent, appearing<br />

26 times as the second half of the 12-<br />

note motive that runs throughout the 18-<br />

measure piece.<br />

<strong>June</strong> <strong>2006</strong> Page 9

Like Praeludium XV, Praeludium XI<br />

modulates to D major and E minor and in<br />

mm. 9 and 10 has a sequence of four dominants<br />

(F ♯ , B, E, A) of which Dave Brubeck<br />

would also have been proud. The leading<br />

tones alternate ostentatiously between the<br />

two voices (A ♯ , D ♯ , G ♯ , C ♯ ).<br />

Trilling each of those leading tones<br />

offers a fingering challenge. A ♯ to B is easy<br />

fingering A ♯ 1/1 and wiggling the right<br />

index finger. The only other fingering that<br />

tunes well (LH fork key for A ♯ ) cannot be<br />

reached preceded by E. The D ♯ trill can<br />

also be fingered 1/1 with ease, but in this<br />

register, the D ♯ will be sharp. The best D ♯<br />

trill is rather odd: To the first finger LH<br />

add all three RH fingers plus the low E<br />

key, then wiggle the three fingers while<br />

leaving the E key down. It tunes well and<br />

Page 10<br />

is surprisingly easy. For both of these trills,<br />

avoid using the side key because the upper<br />

note becomes way too sharp.<br />

Unfortunately, there are no fancy fingerings<br />

for the trills in m. 10, but there is<br />

one trick to make them easier. Maintain<br />

the fingers’ shape in the down position<br />

while lifting them, so that the pinky stays<br />

lower than the ring finger. Pretend that<br />

there is a rubber band around the two fingers<br />

and move them as a unit. Obviously,<br />

these trills are not the easiest to begin<br />

with, so we’ll investigate an elementary<br />

approach to trills in our next installment.<br />

A surprise F ♮ breaks the circle of 5ths<br />

and veers into a jazzy new sequence:<br />

GMm 7 , FM 7 , and EMm 7 . There ensues<br />

another sequence of four dominants (E, A,<br />

D, G) resolving not to a CM triad, but to a<br />

THE CLARINET<br />

CM 7 (m. 14) which becomes a ninth chord<br />

by adding a D before moving on to an<br />

Am 7 chord. This is jazz harmony anticipated<br />

by two centuries, and an amazingly<br />

rich palette of seventh chords for a student<br />

to practice in the context of a small, lovely<br />

musical gem.<br />

Motivically, the first six notes do not<br />

constitute a seventh chord as the second<br />

six do, but if they start on the fifth of a<br />

chord, as in m. 2, another set of seventh<br />

chords is created. Consequently this 18-bar<br />

piece has 16 different seventh chords to<br />

practice: six major-minor sevenths, five<br />

diminished-minor sevenths, three major<br />

sevenths, and two minor sevenths.<br />

Bach, however, was thinking of the<br />

first six notes as a triad with lower neighboring<br />

tones as in m. 1. If it happens to be<br />

a seventh chord, as in m. 2, it is incidental<br />

and coincidental. As a result, there are<br />

two times when a minor triad has a raised<br />

lower neighboring tone (Em plus D ♯ in<br />

m. 5 and Am plus G ♯ in m. 11). The resulting<br />

seventh chord (a minor-major seventh),<br />

is not part of Bach’s harmonic language<br />

nor the language of the 19th century.<br />

Thus it does not appear in my arpeggio<br />

studies, nor in any others that I know of.<br />

But it is a part of 20th-century language,<br />

especially movie music, and could be<br />

added to an arpeggio routine if desired.<br />

Speaking of 20th-century harmony, notice<br />

that Bach was not afraid of dissonance.<br />

Examples abound in his works, and one of<br />

the best is in m. 7. The chord progression<br />

is as normal as could be (IV, VII 7 in E<br />

minor), but keeping the shape of the 12-<br />

note motive in the lower voice is paramount.<br />

As a result, the sixth eighth note of<br />

the bar brings the striking juxtaposition of<br />

E and D ♯ . It doesn’t last very long, but it<br />

will certainly wake up anyone who might<br />

have been dozing off. There are a few<br />

other dissonances in this short piece, most<br />

notably the major sevenths between C and<br />

B in m. 14, but they are not quite as spicy<br />

as in m. 7.<br />

In music that is essentially linear such<br />

as these examples, most appearances of the<br />

dominant are more veiled. In the Menuet<br />

from Bach’s English Suite (see Example<br />

17), the underlying harmony contains dominants<br />

in m. 4 (Cm) and mm. 6, 7, 11, and<br />

13 (E ♭ M). It is particularly obscured by<br />

the unusual voice leading in m. 13. Contemporary<br />

purists would have scoffed at<br />

the perfect fifth (G-D) leading in parallel<br />

motion to the perfect fourth (F-B ♭ ), but

Bach didn’t care. The melodic construction<br />

of the voices superseded such trivial harmonic<br />

issues, just as it did in m. 7 of Praeludium<br />

XI. Here the lines are scalar rather<br />

than chordal and we will be drawing upon<br />

Although this piece includes a very<br />

nice sequence of seventh chords with the<br />

same melodic outline as in Praeludium<br />

XI, the main reason it is included occurs<br />

in mm. 14–15, and again in mm. 26–29,<br />

in which the VII 7 and V 7 overlap to create<br />

a very rich dominant. M. 14 contains an incomplete<br />

VII 7 in F minor (E-G-D ♭ ) and the<br />

first beat of m. 15 hints at one of Beethoven’s<br />

favorite chords, the Mmm 9 , which<br />

consists of a VII 7 stacked atop a V 7 . See<br />

m. 280 of the Eroica Symphony for a dramatic<br />

example.<br />

The D ♮ on beat two of m. 15 dispels the<br />

minor ninth and leads to a calm resolution<br />

via a melodic minor scale. The second<br />

example is more Beethovenian, climaxing<br />

in m. 29 with all five notes of the Mmm 9<br />

(G-B-D-F-A ♭ ). Our goal is to enjoy the<br />

richness of that moment (G with A ♭ , A ♮<br />

with G, B ♮ with E ♭ ), and to hear it all as a<br />

super dominant in C minor. Through the<br />

genius of Bach, the greatest religious<br />

composer ever, we can arrive in “Seventh<br />

our scales rather than arpeggios for practice.<br />

Still, the B ♭ in the bass should signal<br />

“dominant” and the E ♮ in the next measure<br />

(m. 14) should warn of a modulation to F<br />

minor via the leading tone.<br />

Heaven” by using his music to practice<br />

our arpeggios.<br />

WEBSTER’S WEB<br />

My friend Richard Nunemaker, bass<br />

clarinetist of the Houston Symphony and<br />

strong advocate of contemporary music<br />

responded to my thoughts about the hurricane<br />

victims:<br />

What wonderful words you had to say in<br />

this month’s “Webster’s Web.” All of us<br />

indeed are so fortunate to be able to experience<br />

the joy of music. Some of us are even<br />

more fortunate than others to actually be<br />

able to perform music as a career choice.<br />

Life does not get any better than that. Each<br />

day I arise I give thanks to be so blessed.<br />

Yes, we must remember all those who<br />

are less fortunate than us. As musicians<br />

and artists we can spread the joy of sharing<br />

music and its healing powers at our<br />

performance venues, in our teaching studios<br />

and at our community service performances.<br />

And, taking your advice, do what<br />

each of us can, to help equalize education,<br />

economic opportunities, and quality health<br />

care for all. Thanks for giving us pause to<br />

think about the fragility of life and to be<br />

grateful for each day as they come.<br />

A clarinetist who exemplifies appreciation<br />

of our good fortune in making a living<br />

from doing something we love is Lorenzo<br />

Coppola, who visited Rice to perform<br />

with Context, an organization founded<br />

by Sergiu Luca dedicated to performances<br />

on period instruments. He performed<br />

the Mozart Quintet on his “<strong>Clarinet</strong>to<br />

d’amore,” a basset clarinet in A with<br />

the same kind of bulbous bell as an oboe<br />

d’amore. While here, he visited both of<br />

my weekly studio classes, coaching a student<br />

group in the Mozart Quintet, performing<br />

the Mozart Concerto for us, accompanied<br />

by an early 19th-century Graf piano<br />

tuned to A=430, and allowing me to<br />

try his precious instrument.<br />

The coaching was eye-opening. With<br />

playful persuasiveness and excellent English,<br />

he had the students totally rethink<br />

their approach to the Mozart, especially<br />

in terms of tapered phrasing rather than<br />

long sustained lines, the concept of appoggiatura<br />

and cadence, and in putting<br />

expression in the bow, with little or no<br />

help from vibrato.<br />

His clarinetto d’amore is a replica of<br />

the soft-voiced instrument that Stadler<br />

probably used. Lorenzo pointed out that<br />

the first performance of the concerto had<br />

six violins, two violas, two cellos, and one<br />

bass and that the winds in the orchestra<br />

never play with the solo voice, thus preventing<br />

balance problems.<br />

My admiration for his mastery of this<br />

instrument grew exponentially when I<br />

tried to play it myself. He gave me a minilesson<br />

in front of my students, who had a<br />

great time seeing their teacher struggle<br />

with the cross fingerings, the incredibly<br />

poor intonation, and the extremely weak<br />

reed. You can’t imagine the lengths that<br />

period players must go to in order to play<br />

in tune until you try it yourself. I’ll leave it<br />

to Lorenzo, who spent five days at my<br />

home and was a joy to be around. I don’t<br />

think anyone’s understanding of the clarinet<br />

can be complete without hearing historical<br />

instruments live. Recordings just<br />

don’t give an inkling of the quiet purity of<br />

the sound and the machinations of fingering<br />

and embouchure necessary to achieve<br />

it. Thank you, Lorenzo.<br />

<strong>June</strong> <strong>2006</strong> Page 11

Buddy DeFranco<br />

Among Honorees Named<br />

NEA Jazz Masters<br />

Initiated in 1982, the NEA Jazz Master<br />

title is the nation’s highest honor in this<br />

distinctively American art form. In addition<br />

to the coveted designation, each member<br />

of the Class of <strong>2006</strong> will receive a fellowship<br />

award of $25,000 and be invited<br />

to participate in outreach efforts, including<br />

broadcasts and NEA Jazz Masters On Tour.<br />

The NEA Jazz Master Award is part of<br />

the NEA Jazz Masters Initiative and is<br />

sponsored by Verizon. Through its support<br />

of this initiative, Verizon continues its tradition<br />

of supporting quality musical entertainment<br />

and education across the country.<br />

The seven new NEA Jazz Masters are<br />

Ray Barretto (percussionist), Tony Bennett<br />

(vocalist), Bob Brookmeyer (arrangercomposer),<br />

Chick Corea (keyboardist),<br />

Buddy DeFranco (solo instrumentalist,<br />

clarinet), Freddy Hubbard (solo instrumentalist,<br />

trumpet), and John Levy (A.B. Spellman<br />

NEA Jazz Masters Award for Jazz<br />

Advocacy, for his career as a manager).<br />

In addition, the A.B. Spellman NEA<br />

Jazz Masters Award for Jazz Advocacy,<br />

named in honor of the noted jazz critic,<br />

historian, and poet who served for many<br />

years as a Deputy Chairman of the Arts<br />

Endowment, is given this year to John<br />

Levy. A talented bassist, Levy in 1951<br />

became the first African-American to work<br />

as a personal manager in the music industry<br />

— a career that he has now pursued<br />

successfully for half a century.<br />

The seven new NEA Jazz Masters received<br />

their awards in January <strong>2006</strong> at a<br />

gala concert in New York City, presented<br />

under the auspices of the annual convention<br />

of the <strong>International</strong> <strong>Association</strong> for<br />

Jazz Education.<br />

News from Paris<br />

A competition was held on February 12<br />

for the E ♭ clarinet position in the Orchestra<br />

National de France in Paris, and it was<br />

won by Jessica Bessac succeeding Gilbert<br />

Monier. Since 2005, Bessac has been the<br />

E ♭ clarinetist in the Orchestre d’Ile de<br />

France. The 1st Soloist in the Orchestre<br />

National since 2003 is Patrick Messina, a<br />

chair previously occupied by Guy Dangain<br />

and Alessandro Carbonare. The co-principal<br />

clarinet since 2004 is Nicolas Baldeyrou.<br />

In the orchestra of the Opera de Paris<br />

the 2nd Soloist since 2004 is Alexandre<br />

Chabod, the chair formerly occupied by<br />

Philippe Cuper, now Super-Soloist with<br />

Jean-François Verdier.<br />

At the Ensemble Orchestral de Paris,<br />

the 2nd Soloist/bass clarinetist since 2004<br />

is Florent Pujuila, the Third Prize winner<br />

in the Munich Competition in 2003, and<br />

the 1st Soloist is Richard Vieille. The clarinetists<br />

in the Ensemble Intercontemporain<br />

(founded by Pierre Boulez) include 1st<br />

Soloist Alain Damiens, bass clarinetist Sébastien<br />

Billard and, since March of 2005,<br />

the 2nd Soloist is Jérome Comte who replaced<br />

André Trouttet.<br />

At the Paris Conservatoire, two rounds<br />

of entrance auditions were held to fill the<br />

six vacancies for clarinet students. The required<br />

repertoire included in round one: F.<br />

Berr, Etude No. 12 sur un theme de Paganini<br />

(from 12 Etudes Mélodiques, and L.<br />

Cahuzac’s Arlequin; round two: A. Messager,<br />

Solo de concours and Lutoslawski,<br />

Dance Preludes. From the 52 candidates<br />

competing in the first round, 13 were selected<br />

for the final round. The following<br />

were chosen: Roman Millard (from the<br />

Conservatoire National de Region de Paris,<br />

class of Richard Vieille), Romy Bischoff<br />

(from the Conservatoire National de<br />

Region de Paris, class of Richard Vieille),<br />

Akima Yoshino (Japan, Conservatoire<br />

12th Arrondissement, Paris), Florence<br />

Bouillot (Conservatoire National de Region<br />

of Rueil-Malmaison, class of Michel<br />

Arrignon and Florent Héau), Frank Russo<br />

(also from Conservatoire National de Region<br />

of Rueil-Malmaison) and Yung-Nyen<br />

(Taiwan, also from Conservatoire National<br />

de Region of Rueil-Malmaison). The<br />

current professors of clarinet at the Paris<br />

Conservatoire are Michel Arrignon with a<br />

class of 12 students and Pascal Moraguès<br />

with a class of six students.<br />

[Merci to Jean-Marie Paul. Ed.]<br />

Woodwind Dictionary<br />

Online<br />

Molem Woodwind Atelier is proud to<br />

announce WOODWINDWORDS, a free<br />

online woodwind dictionary: . Woodwindwords<br />

allows users to translate woodwind terminology<br />

from English into German and<br />

French, and vice versa. It currently contains<br />

around 5,000 entries concerning<br />

instruments, accessories, materials, tools,<br />

repair, fabrication, and other related fields.<br />

Molem, , is a<br />

workshop for the making, repairing, and<br />

restoring of woodwind instruments, situated<br />

near Paris and founded by Mona Lemmel.<br />

For more information please contact<br />

.<br />

Visit the I.C.A.<br />

on the World Wide Web:<br />

www.clarinet.org<br />

Page 12<br />

THE CLARINET

<strong>June</strong> <strong>2006</strong> Page 13

Page 14<br />

by William Nichols<br />

Composers Recordings, Inc. (CRI),<br />

founded in 1954, was for nearly<br />

50 years, by their own description,<br />

“America’s premier new music label.”<br />

Sadly the label ceased operation<br />

about three years ago. Its collection of<br />

20th-century repertoire, almost exclusively<br />

American, is immense and diversified<br />

in style and medium. CRI existed as a<br />

nonprofit corporation supported by private<br />

foundations, universities and individuals.<br />

Its catalog chronicles a vast history<br />

of American concert music from mid-century<br />

to the present.<br />

Fortunately New World Records has<br />

recently acquired CRI’s assets. According<br />

to New World’s Director of Artists and<br />

Repertory, Paul Tai, they plan to make the<br />

complete CRI CD catalog available as<br />

“burn-on-demand CDs” beginning in the<br />

fall of <strong>2006</strong>. In addition about three to<br />

four CRI titles per year, over the next few<br />

years, are being reissued on New World<br />

Records, beginning just last April.<br />

Also very fortunately, much of the CRI<br />

CD catalogue is still available, and at bargain<br />

basement prices of $3.50 to $4.00 per<br />

disc! At least two sources, Qualiton Imports,<br />

Ltd. () and<br />

Berkshire Record Outlet () are currently (2/06)<br />

offering over 200 titles. This enables<br />

adventuresome clarinetists and lovers of<br />

contemporary music, and the curious, an<br />

affordable chance to sample, in many<br />

cases, unknown repertoire and also to hear<br />

many fine players, some of which are<br />

among the finest “new music” artists of the<br />

present and past decades.<br />

Following is a list of CD releases of<br />

possible interest to clarinetists. This is certainly<br />

not a comprehensive listing of all the<br />

CRI titles which feature clarinet works or<br />

prominent ensemble playing by clarinetists,<br />

however it is a substantial effort to<br />

that end. The discs included present at least<br />

one solo or small chamber work for clarinet,<br />

or a work with chamber ensemble<br />

accompaniment in which prominent clarinetists<br />

are indicated as personnel. Generally<br />

only clarinet works are included in<br />

the listing, and other works which may<br />

also be on the disc are omitted for the sake<br />

of time and space, as are non-clarinetist<br />

performers. The first 20 items listed were<br />

examined for this study and will contain<br />

brief critical comment and special recommendation.<br />

The remainder of this rather<br />

extensive array of recordings consists only<br />

of basic information:<br />

CRI 609 — Shulamit Ran: Concerto da<br />

Camera II for clarinet, string quartet<br />

and piano/Edward Gilmore, clarinet;<br />

Apprehensions for voice, clarinet and<br />

piano/Laura Flax, clarinet; Private<br />

Game for clarinet and cello/Laura Flax,<br />

clarinet. This disc contains exciting<br />

music presented by two leading clarinetists<br />

in the new music field. There is<br />

brilliant playing by Edward Gilmore,<br />

and among other aspects some amazing<br />

altissimo control by the Da Capo Chamber<br />

Players’ Laura Flax — strongly recommended.<br />

CRI 725 — Roberto Sierra: Pieza Características<br />

for sextet including bass clarinet;<br />

Ritmorroto for solo clarinet; Tres<br />

Fantasías for clarinet, cello and piano;<br />

Cinco Bocetos for solo clarinet; Con<br />

Tres for clarinet, bassoon and piano/<br />

William Helmers, clarinet and bass<br />

clarinet. This is a stellar disc of interesting<br />

music beautifully performed by this<br />

Milwaukee based clarinetist. A favorable<br />

review by Linda Bartley appears<br />

in the May/<strong>June</strong>, 1998 issue of The<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong>.<br />

CRI 893 — Barbara White: the mind’s<br />

fear, the heart’s delight, and LIFE in<br />

the castle with the New York New Music<br />

Ensemble/Jean Kopperud, clarinet<br />

and bass clarinet; when the SMOKE<br />

clears for clarinet, violin and marimba/Michael<br />

Lowenstern, clarinet; noman’s<br />

LAND, for solo clarinet, with<br />

composer/clarinetist Barbara White.<br />

Exciting playing of interesting music by<br />

THE CLARINET<br />

the well-known Jean Kopperud and<br />

Michael Lowenstern, as well as accomplished<br />

playing by Barbara White.<br />

CRI 693 — Donald Martino: A Set for<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong>/Michael Webster, clarinet;<br />

Trio for violin, clarinet and piano/Arthur<br />

Bloom, clarinet; Concerto for Wind<br />

Quintet/the Contemporary Chamber<br />

Ensemble of Rutgers University (personnel<br />

not indicated); and Strata for<br />

Bass <strong>Clarinet</strong>/Dennis Smylie, bass clarinet.<br />

This compilation from five CRI<br />

vinyl discs is a must for serious clarinetists.<br />

The Set and Strata have become<br />

classic repertoire of their genre<br />

from an important American composer<br />

for the clarinet. Dennis Smylie’s performance<br />

is amazing.<br />

CRI 773 — Robert X. Rodriquez: Les<br />

Niais Amoureux for violin, clarinet,<br />

cello and piano; Mario Davidovsky:<br />

Romancero for soprano, flute, clarinet,<br />

violin and cello; Mario Lavista: Madrigal<br />

for solo clarinet. The ensemble here<br />

is the Dallas-based Voices of Change<br />

with longtime member clarinetist Ross<br />

Powell. The program is by composers<br />

with Hispanic connections. The music<br />

is colorful and beautifully played, and<br />

vividly recorded — great sound.<br />

CRI 821 — Margaret Brouwer: Prelude<br />

and Vivace for clarinet and chamber<br />

orchestra/Daniel Silver, clarinet. This is<br />

the chamber orchestra version of the<br />

Concerto for <strong>Clarinet</strong> which was recorded<br />

by Richard Stoltzman and reviewed<br />

in these pages some years ago.<br />

This is an attractive and charming work<br />

played very effectively by Daniel Silver<br />

and the Cleveland Institute of Music<br />

New Music Ensemble. Great sound and<br />

performance — strongly recommended<br />

CRI 886 — Cindy Cox: Geode for flute,<br />

clarinet, cello, percussion and piano;<br />

and Primary Colors for violin, clarinet<br />

and piano/Peter Joseff, clarinet and bass<br />

clarinet (in Geode with the Earplay Ensemble).<br />

Imaginative pieces well performed<br />

— recommended.

CRI 724 — Philip Batstone: A Mother<br />

Goose Primer. This disc is a tribute to<br />

soprano Bethany Beardslee who is accompanied<br />

in this work by the U.C.L.A.<br />

Chamber Ensemble of eight members,<br />

who include clarinetists Gary Gray,<br />

Gary Foster, and bass clarinetist David<br />

Atkins. This disc is recommended not<br />

primarily for the excellent playing of<br />

the clarinetists (which indeed is the<br />

case), but for the amazing artistry displayed<br />

by Bethany Beardslee, one of<br />

the most significant performers of new<br />

music of her time.<br />

CRI 897 — Martin Boykan: Flume for<br />

clarinet and piano/Ian Greitzer, clarinet.<br />

This is very good sounding disc which<br />

presents New England-based Ian Greitzer<br />

in an impressive performance of an<br />

interesting 10-and-a-half minute work<br />

from 1998.<br />

CRI 775 — Howard Boatwright: Sonata<br />

for clarinet and piano/Michael Webster,<br />

clarinet. This sonata (completed in<br />

1983) is a significant addition to the<br />

repertory. It is captured here in an excellent<br />

live performance from the rather<br />

dry recording acoustic of the Everson<br />

Museum of Syracuse.<br />

CRI 835 — Ronald Caltabiano: Hexagons<br />

for wind quintet and piano/Alan R.<br />

Kay, clarinet; and Concertini (15 instrument<br />

version). The players of Hexagon<br />

are from the Hexagon Ensemble,<br />

based in New Jersey. The music presents<br />

striking sounds and a rugged<br />

rhythmic style, and the lyrical passages<br />

are particularly effective. Alan Kay<br />

sounds terrific in this significant new<br />

work in the wind quintet-piano repertoire.<br />

The Concertini is performed with<br />

total commitment by the stellar Group<br />

for Contemporary Music, with clarinetist<br />

Charles Neidich in the ensemble,<br />

conducted by the composer.<br />

CRI 743 — Harvey Sollberger: Chamber<br />

Variations; and Riding the Wind I. The<br />

Chamber Variations, recorded in 1964,<br />

is performed by 12 members of The<br />

Group for Contemporary Music conducted<br />

by Gunther Schuller. The clarinetist/bass<br />

clarinetist in this rugged serial<br />

work is Efrain Guigui. Riding the<br />

Wind I (1973) is a chamber concerto for<br />

flute and the remaining four members<br />

of the Da Capo Chamber Players, including<br />

clarinetist Allen Blustine. The<br />

recording is conducted by the composer<br />

and world-class flutist Harvey Sollberger,<br />

and features one of this writer’s favorite<br />

flutists — the sensational Patricia<br />

Spencer — who is not to be missed in<br />

this performance.<br />

CRI 721 — William Hibbard: Bass Trombone,<br />

Bass <strong>Clarinet</strong>, Harp/Charles West,<br />

bass clarinet. Included in a production<br />

entitled Gay American Composers featuring<br />

works by 13 composers, Hibbard’s<br />

piece is a tightly constructed fascinating<br />

work beautifully played and<br />

recorded.<br />

CRI 758 — Phillip Rhodes: Museum<br />

Pieces for clarinet and string quartet/<br />

James Livingston, clarinet. This is a<br />

very good 17-and-a-half minute piece<br />

in six movements well played by Louisville<br />

Orchestra principal clarinetist, and<br />

the Louisville String Quartet. The work<br />

is programmatic in concept, related to<br />

Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition<br />

or Gunther Schuller’s Seven Studies on<br />

Paul Klee — recommended.<br />

CRI 817 — Ernst Krenek: Trois Chansons,<br />

Op. 30a for soprano, clarinet and<br />

string quartet/William Nichols, clarinet;<br />

Richard Wernick: Haiku of Basho; and<br />

R. Murray Schafer: Requiems for the<br />

Party-Girl. Wernick and Schafer are<br />

with the Contemporary Chamber Players<br />

of the University of Chicago/Stanley<br />

Davis, clarinet, bass clarinet and E ♭<br />

clarinet. This disc features soprano and<br />

longtime exponent of contemporary<br />

music Neva Pilgrim. (Further comment<br />

here is perhaps inappropriate.)<br />

CRI 665 — Frederic Goossen: Sonata for<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> and Piano/Scott Bridges, clarinet.<br />

This sonata from 1986 is a 17-<br />

minute work, substantial in content and<br />

at times quite virtuosic. It receives excellent<br />

playing by the facile Scott Bridges<br />

and pianist Patricia Perez Hood.<br />

CRI 735 — Marc-Antonio Consoli: Vuci<br />

Siculani for mezzo soprano and seven<br />

players/Bernard Yannotta, clarinet; and<br />

DI. VER. TI. MENTO for clarinet, alto<br />

saxophone, French horn, and trombone/Esther<br />

Lamneck, clarinet. These<br />

two Consoli pieces are if not somewhat<br />

at odds, products of different sound<br />

concepts. The Vuci Siculani is in great<br />

part exotic, with interwoven atonal<br />

melodies, sometimes chant-like, and<br />

generally transparent in texture. The<br />

piece for winds (subtitled Games for 4)<br />

is at times quite dense and rhythmically<br />

driven. The challenging upper altissimo<br />

playing by Esther Lamneck is skillfully<br />

handled. The colors and character of<br />

Vuci Siculani is sensually beautiful.<br />

CRI 705 — David Sanford: Chamber<br />

Concerto No. 3/Allen Blustine, clarinet;<br />

Morris Rosenzweig: Delta, the Perfect<br />

King (Chamber Concerto for Horn);<br />

Eric Moe: Kicking and Screaming. The<br />

Rosenzweig and Moe accompanying<br />

ensembles of 11 and 10 players respectively,<br />

include David Krakauer, clarinet,<br />

and Dennis Smylie, clarinet/bass clarinet<br />

(Rosenzweig), and Allen Blustine<br />

(Moe). The modestly scored (oboe, bassoon,<br />

violin, cello and piano) Sanford<br />

chamber concerto is expertly played by<br />

Allen Blustine. These are brilliant virtuoso<br />

performances by the highly regarded<br />

Speculum Musicae of New York.<br />

CRI 784 — Ezra Sims: “String Quartet<br />

No. 2” (1962) for flute, clarinet,violin,<br />

viola and cello; Elegie–nach Rilke for<br />

soprano, flute, clarinet, violin, viola<br />

and cello. Boston Musica Viva/William<br />

Wrzesien, clarinet. Inspite of the title of<br />

the first work, it is not a string quartet.<br />

This disc affords a rare listening experience<br />

of hearing the clarinet used in<br />

microtonal ensemble works.<br />

CRI 788 — George Tsontakis: Three<br />

Mood Sketches for wind quintet; Alvin<br />

Etler: Concerto for Violin and Wind<br />

Quintet; and Bruce Adolphe: Chiaroscuro<br />

for double wind quintet. Sylvan<br />

Winds/Alan R. Kay, clarinet, and Jo-<br />

Ann Sternberg, clarinet (in Adolphe).<br />

David Chaitkin: Summersong for 23<br />

winds/Charles Neidich, Robert Yamins,<br />

Steven Hartman, clarinets. Excellent<br />

American wind works beautifully performed<br />

and recorded — the first, only,<br />

and long overdue commercial recording<br />

of the Etler work.<br />

Additional available CRI recordings<br />

without critical comment:<br />

CRI 663 — Leroy Jenkins: Themes and<br />

Improvisations on the Blues/Don Byron,<br />

clarinet/Mary Ehrilich, bass clarinet.<br />

CRI 669 — Für Wolfgang Amadeus:<br />

music by Donald Crockett, Stephen<br />

Hartke, Libby Larsen, and Rand Steiger,<br />

with the LA Chamber Orchestra/<br />

Gary Gray, clarinet.<br />

<strong>June</strong> <strong>2006</strong> Page 15

CRI 594 — John McLennan: Quintet for<br />

violin, viola, cello, clarinet and piano/<br />

Peter Hadcock, clarinet.<br />

CRI 7<strong>33</strong> — The Music of Frank Wigglesworth:<br />

Summer Music for Bass <strong>Clarinet</strong>/<br />

Evan Ziporyn, bass clarinet.<br />

CRI 736 — Ellsworth Milburn: Menil<br />

Antiphons for eight players/David Peck,<br />

clarinet.<br />

CRI 739 — Louis Karchin: Galactic Folds<br />

with New York New Music Ensemble/Jean<br />

Kopperud, clarinet; and Songs<br />

of Distance and Light/Jean Kopperud,<br />

bass clarinet.<br />

CRI 755 — Victoria Jordanova: Mute<br />

Dance for clarinet, harp, percussion and<br />

sampled sounds/Laura Carmichael,<br />

clarinet.<br />

CRI 787 — Morris Rosenzweig: Angels,<br />

Emeralds, and the Towers, with the<br />

Canyonland Ensemble/Jaren Hinckley,<br />

clarinet; On the Wings of Wind/Jaren<br />

Hinckley, clarinet and bass clarinet.<br />

CRI 790 — Robert Savage: Frost Free for<br />

clarinet and piano/Tim Smith, clarinet.<br />

CRI 793 — Seymour Shifrin: Serenade for<br />

Five Instruments/Charles Russo, clarinet.<br />

CRI 799 — Leo Kraft: Omagio for flute,<br />

clarinet, violin, viola and cello/Jean<br />

Kopperud, clarinet.<br />

CRI 841 — Martin Boykan: Echoes of<br />

Petrarch for flute, clarinet and piano/<br />

William Kirkley, clarinet.<br />

CRI 842 — Walter Winslow: Mirror of<br />

Diana for solo clarinet/Jean Kopperud,<br />

clarinet.<br />

CRI 846 — Barton McLean: Ritual of the<br />

Dawn for flute, clarinet, harp, piano<br />

and percussion/E. Michael Richards,<br />

clarinet.<br />

CRI 849 — P.Q. Phan: Beyond the Mountains<br />

for clarinet, violin, cello and<br />

piano; and My Language for clarinet<br />

and piano/E. Michael Richards, clarinet.<br />

CRI 863 — Edward Smaldone: Two Sides<br />

of the Same Coin for clarinet and piano;<br />

and Trio: Dance and Nocturne/Allen<br />

Blustine, clarinet.<br />

CRI 866 — Music of Wadada Smith, Michael<br />

Fink, Bernardo Feldman, Barney<br />

Childs, Arthur Jarvinen, Shaun Naidoo,<br />

and Jim Fox/Marty Walker, bass<br />

clarinet.<br />

CRI 823 — Wendell Logan: Runagate,<br />

Runagate/ Suzanne Hickman, clarinet.<br />

CRI 860 — Hale Smith: Dialoquest<br />

Commentaries for seven players, with<br />

Boston Musica Viva/William Wrzesien,<br />

clarinet.<br />

CRI 885 — Eleanor Cory: Of Mere Being,<br />

St. Luke’s Chamber Ensemble/William<br />

Blount, clarinet; and Bouquet for eight<br />

players, New York New Music Ensemble/Jean<br />

Kopperud, clarinet.<br />

CRI 879 — Gerald Cohen: Generations<br />

And You Shall Tell Your Child for four<br />

players and chorus/David Abrams,<br />

clarinet.<br />

CRI 882 — Karl Korte: Matrix for wind<br />

quintet, piano, saxophone and percussion,<br />

with the New York Wind Quintet/David<br />

Glazer, clarinet.<br />

CRI 759 — Brian Fennelly: Evanescences,<br />

Da Capo Chamber Players/Allen Blustine,<br />

clarinet; and Wind Quintet, Dorian<br />

Quintet/Jerry Kirkbride, clarinet.<br />

CRI 889 — Kitty Brazelton: Sonata for the<br />

Inner Ear for seven players/Marty Walker,<br />

bass clarinet.<br />

CRI 8<strong>33</strong> — Louise Talma: 3 Duologues<br />

for clarinet and piano/Gregory Oakes,<br />

clarinet.<br />

CRI 598 — Elliott Schwarz: Chamber<br />

Concerto No. 2 for clarinet and nine<br />

instruments/Paul Zonn, clarinet; Extended<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> for clarinet and tape,<br />

and Souvenir for clarinet and piano/<br />

Jerome Bunke, clarinet.<br />

CRI 881 — Dan Welcher: Phaedrus for<br />

clarinet, violin and piano; and Dante<br />

Dances for clarinet and piano/clarinetist<br />

unknown.<br />

CRI 779 — Ernst Bacon: Remembering<br />

Ansel Adams for clarinet and orchestra/Richard<br />

Stoltzman, clarinet.<br />

CRI 612 — Robert Starer: Concerto a Tre<br />

for clarinet, trumpet and trombone and<br />

strings/Joseph Rabbai, clarinet.<br />

CRI 870 — Robert Maggio: Riddle for<br />

violin, clarinet and piano/Nathan Williams,<br />

clarinet.<br />

CRI 862 — Jennifer Barker: The Enchanted<br />

Glen for clarinet and piano/Melanie<br />

Richards, clarinet.<br />

CRI 565 — David Olan: Composition for<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> and Tape/Laura Flax, clarinet.<br />

Good listening!<br />

The <strong>Clarinet</strong><br />

PUBLICATION SCHEDULE<br />

The magazine is usually mailed<br />

during the last week of Feb ruary,<br />

May, August and No vem ber. De -<br />

livery time within North America<br />

is nor mally 10–14 days, while airmail<br />

delivery time outside North<br />

America is 7–10 days.<br />

Page 16<br />

THE CLARINET

<strong>June</strong> <strong>2006</strong> Page 17

JEUNE ORCHESTRE<br />

ATLANTIQUE<br />

DISCOVERY COURSE<br />

A Report by Marie Ross<br />

In October 2005 the Jeune Orchestre<br />

Atlantique held its first week-long<br />

discovery course at the Abbaye aux<br />

Dames in Saintes, France. The Jeune Or -<br />

chestre Atlantique is a classical period<br />

instrument training orchestra. This special<br />

course, an idea of the clarinetist Jane<br />

Booth, was designed for musicians used to<br />

playing on modern instruments to learn<br />

about and gain experience on period in -<br />

struments. Ms. Booth plays principal clarinet<br />

in the Orchestre des Champs-Ély sées<br />

and is the education manager for the<br />

orchestra as well as an avid teacher.<br />

The course included both winds and<br />

strings, and was taught by members of<br />

the Orchestre des Champs-Élysées, one of<br />

Page 18<br />

Europe’s premiere period-instrument or -<br />

chestras. All of the teachers were proficient<br />

in both French and English and<br />

always repeated everything in both languages<br />

for the sake of the many international<br />

students.<br />

Jane Booth brought many classical<br />

reproduction clarinets with various numbers<br />

of keys for the participants to play.<br />

There were also basset clarinets and basset<br />

horns which were passed around amongst<br />

the group. The chance to play on so many<br />

rare clarinets would be amazing for any<br />

clarinetist, but this course was about forgetting<br />

the virtuosic technicalities of an<br />

instrument and focusing on the real ex -<br />

pression of music. The students learned<br />

from these truly masterful musicians how<br />

a classical-period performer would make<br />

a phrase, something that has been lost<br />

through centuries of musical evolution.<br />

One might think that learning to play<br />

early clarinets with only a few keys would<br />

be a huge shock compared to the modern<br />

clarinet. It is a shock, but not in the way<br />

THE CLARINET<br />

one might expect. The first night many lips<br />

were swollen from biting the clarinet<br />

mouthpiece trying to force a “good” modern<br />

sound out of the instrument. But soon<br />

the participants were taught to relax and<br />

play with the unique and personal colors of<br />

the classical instruments. These instruments<br />

are so much more flexible, and, as a<br />

result, a player can achieve different pitches<br />

and colors as a piece demands. These<br />

ideas are all lost today with the generically<br />

perfect sound of modern instruments,<br />

which have evolved to the point of complete<br />

stability and inflexibility.<br />

Each day there were lectures given by<br />

the teachers on various topics of period<br />

music performance. One of the highlights<br />

was Marcel Ponseele speaking about how<br />

he made his own oboes. At first when he<br />

said this would be his topic, a few students<br />

thought he was joking because the idea of<br />

making your own instrument is completely<br />

foreign to most modern musicians. With<br />

this came the realization that as musicians<br />

living in our modern world, perhaps we<br />

can never really understand classicalperiod<br />

music as the musicians of the time<br />

experienced it. He brought oboes in all<br />

stages of assembly, some of his tools, and<br />

even demonstrated how he constructs the<br />

curved oboe da caccia. Seeing the raw<br />

wood through its different stages as it was<br />

being crafted into an oboe by one man as<br />

opposed to the impersonal masses of modern<br />

instruments pumped out by factories<br />

was the essence of what period-instrument<br />

playing is about.<br />

Though a complete expert on the clarinet,<br />

period and modern, Jane Booth<br />

proved to be more of a musician than<br />

merely a clarinet player. The students<br />

spent hours frantically writing as Ms.<br />

Booth talked about clarinet makers or different<br />

equipment she experimented with to<br />

achieve certain results. But one definitely<br />

gets the feeling that to her the clarinet is<br />

only an instrument used to express her<br />

musical and creative ideas. This was a pervasive<br />

theme of the course: that period<br />

instrumentalists are seeking an individual<br />

creativity that is too often lost in the cold<br />

technical virtuosity that is prized today.<br />

The afternoons were filled with trying<br />

instruments, chamber music rehearsals and

coachings with various faculty, orchestra<br />

rehearsals conducted by violinist Adrian<br />

Chamorro, and both master classes and<br />

individual lessons with Ms. Booth. By the<br />

end of the week the group was able to perform<br />

a concert at a local church which in -<br />

cluded the first movement of Haydn’s<br />

Sym phony No. 104 and several chamber<br />

pieces, including the Beethoven Trio, Op.<br />

87, and a William Boyce quartet arranged<br />

for three clarinets and bassoon.<br />

The students came away from this ex -<br />

perience with a hunger to perform music<br />

solely on the original instruments. After<br />

attending this course one has to wonder<br />

how we could ever perform a piece like<br />

Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte, originally re -<br />

quiring the unique colors and tones of four<br />

different clarinets including basset horns,<br />