CONFUCIUS THE ANALECTS

CONFUCIUS THE ANALECTS

CONFUCIUS THE ANALECTS

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

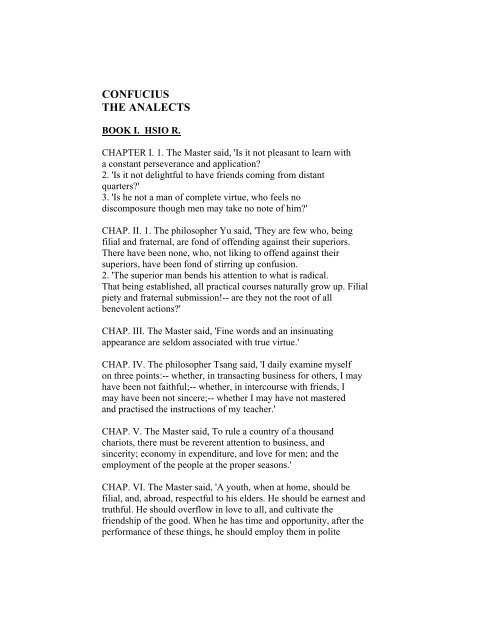

<strong>CONFUCIUS</strong><br />

<strong>THE</strong> <strong>ANALECTS</strong><br />

BOOK I. HSIO R.<br />

CHAPTER I. 1. The Master said, 'Is it not pleasant to learn with<br />

a constant perseverance and application?<br />

2. 'Is it not delightful to have friends coming from distant<br />

quarters?'<br />

3. 'Is he not a man of complete virtue, who feels no<br />

discomposure though men may take no note of him?'<br />

CHAP. II. 1. The philosopher Yu said, 'They are few who, being<br />

filial and fraternal, are fond of offending against their superiors.<br />

There have been none, who, not liking to offend against their<br />

superiors, have been fond of stirring up confusion.<br />

2. 'The superior man bends his attention to what is radical.<br />

That being established, all practical courses naturally grow up. Filial<br />

piety and fraternal submission!-- are they not the root of all<br />

benevolent actions?'<br />

CHAP. III. The Master said, 'Fine words and an insinuating<br />

appearance are seldom associated with true virtue.'<br />

CHAP. IV. The philosopher Tsang said, 'I daily examine myself<br />

on three points:-- whether, in transacting business for others, I may<br />

have been not faithful;-- whether, in intercourse with friends, I<br />

may have been not sincere;-- whether I may have not mastered<br />

and practised the instructions of my teacher.'<br />

CHAP. V. The Master said, To rule a country of a thousand<br />

chariots, there must be reverent attention to business, and<br />

sincerity; economy in expenditure, and love for men; and the<br />

employment of the people at the proper seasons.'<br />

CHAP. VI. The Master said, 'A youth, when at home, should be<br />

filial, and, abroad, respectful to his elders. He should be earnest and<br />

truthful. He should overflow in love to all, and cultivate the<br />

friendship of the good. When he has time and opportunity, after the<br />

performance of these things, he should employ them in polite

studies.'<br />

CHAP. VII. Tsze-hsia said, 'If a man withdraws his mind from<br />

the love of beauty, and applies it as sincerely to the love of the<br />

virtuous; if, in serving his parents, he can exert his utmost strength;<br />

if, in serving his prince, he can devote his life; if, in his intercourse<br />

with his friends, his words are sincere:-- although men say that he<br />

has not learned, I will certainly say that he has.'<br />

CHAP. VIII. 1. The Master said, 'If the scholar be not grave, he<br />

will not call forth any veneration, and his learning will not be solid.<br />

2. 'Hold faithfulness and sincerity as first principles.<br />

3. 'Have no friends not equal to yourself.<br />

4. 'When you have faults, do not fear to abandon them.'<br />

CHAP. IX. The philosopher Tsang said, 'Let there be a careful<br />

attention to perform the funeral rites to parents, and let them be<br />

followed when long gone with the ceremonies of sacrifice;-- then<br />

the virtue of the people will resume its proper excellence.'<br />

CHAP. X. 1. Tsze-ch'in asked Tsze-kung, saying, 'When our master<br />

comes to any country, he does not fail to learn all about its<br />

government. Does he ask his information? or is it given to him?'<br />

2. Tsze-kung said, 'Our master is benign, upright, courteous,<br />

temperate, and complaisant, and thus he gets his information. The<br />

master's mode of asking information!-- is it not different from that<br />

of other men?'<br />

CHAP. XI. The Master said, 'While a man's father is alive, look<br />

at the bent of his will; when his father is dead, look at his conduct.<br />

If for three years he does not alter from the way of his father, he<br />

may be called filial.'<br />

CHAP. XII. 1. The philosopher Yu said, 'In practising the rules of<br />

propriety, a natural ease is to be prized. In the ways prescribed by<br />

the ancient kings, this is the excellent quality, and in things small<br />

and great we follow them.<br />

2. 'Yet it is not to be observed in all cases. If one, knowing<br />

how such ease should be prized, manifests it, without regulating it<br />

by the rules of propriety, this likewise is not to be done.'

CHAP. XIII. The philosopher Yu said, 'When agreements are<br />

made according to what is right, what is spoken can be made good.<br />

When respect is shown according to what is proper, one keeps far from<br />

shame and disgrace. When the parties upon whom a man leans are proper<br />

persons to be intimate with, he can make them his guides and masters.'<br />

CHAP. XIV. The Master said, 'He who aims to be a man of complete<br />

virtue in his food does not seek to gratify his appetite, nor in his dwelling<br />

place does he seek the appliances of ease; he is earnest in what he is doing,<br />

and careful in his speech; he frequents the company of men of principle<br />

that he may be rectified:-- such a person may be said indeed to love to<br />

learn.'<br />

CHAP. XV. 1. Tsze-kung said, 'What do you pronounce<br />

concerning the poor man who yet does not flatter, and the rich man<br />

who is not proud?' The Master replied, 'They will do; but they are not<br />

equal to him, who, though poor, is yet cheerful, and to him, who, though<br />

rich, loves the rules of propriety.'<br />

2. Tsze-kung replied, 'It is said in the Book of Poetry, "As you cut and<br />

then file, as you carve and then polish."-- The meaning is the same, I<br />

apprehend, as that which you have just expressed.'<br />

3. The Master said, 'With one like Ts'ze, I can begin to talk about the odes.<br />

I told him one point, and he knew its proper sequence.'<br />

CHAP. XVI. The Master said, 'I will not be afflicted at men's not knowing<br />

me; I will be afflicted that I do not know men.'<br />

BOOK II. WEI CHANG.<br />

CHAP. I. The Master said, 'He who exercises government by<br />

means of his virtue may be compared to the north polar star, which<br />

keeps its place and all the stars turn towards it.'<br />

CHAP. II. The Master said, 'In the Book of Poetry are three<br />

hundred pieces, but the design of them all may be embraced in one<br />

sentence-- "Having no depraved thoughts."'<br />

CHAP. III. 1. The Master said, 'If the people be led by laws,

and uniformity sought to be given them by punishments, they will<br />

try to avoid the punishment, but have no sense of shame.<br />

2. 'If they be led by virtue, and uniformity sought to be given<br />

them by the rules of propriety, they will have the sense of shame,<br />

and moreover will become good.'<br />

CHAP. IV. 1. The Master said, 'At fifteen, I had my mind bent<br />

on learning.<br />

2. 'At thirty, I stood firm.<br />

3. 'At forty, I had no doubts.<br />

4. 'At fifty, I knew the decrees of Heaven.<br />

5. 'At sixty, my ear was an obedient organ for the reception of<br />

truth.<br />

6. 'At seventy, I could follow what my heart desired, without<br />

transgressing what was right.’<br />

CHAP. V. 1. Mang I asked what filial piety was. The Master<br />

said, 'It is not being disobedient.'<br />

2. Soon after, as Fan Ch'ih was driving him, the Master told<br />

him, saying, 'Mang-sun asked me what filial piety was, and I<br />

answered him,-- "not being disobedient."'<br />

3. Fan Ch'ih said, 'What did you mean?' The Master replied,<br />

'That parents, when alive, be served according to propriety; that,<br />

when dead, they should be buried according to propriety; and that<br />

they should be sacrificed to according to propriety.'<br />

CHAP. VI. Mang Wu asked what filial piety was. The Master<br />

said, 'Parents are anxious lest their children should be sick.'<br />

CHAP. VII. Tsze-yu asked what filial piety was. The Master<br />

said, 'The filial piety of now-a-days means the support of one's<br />

parents. But dogs and horses likewise are able to do something in<br />

the way of support;-- without reverence, what is there to<br />

distinguish the one support given from the other?'<br />

CHAP. VIII. Tsze-hsia asked what filial piety was. The Master<br />

said, 'The difficulty is with the countenance. If, when their elders<br />

have any troublesome affairs, the young take the toil of them, and<br />

if, when the young have wine and food, they set them before their<br />

elders, is THIS to be considered filial piety?'

CHAP. IX. The Master said, 'I have talked with Hui for a whole<br />

day, and he has not made any objection to anything I said;-- as if<br />

he were stupid. He has retired, and I have examined his conduct<br />

when away from me, and found him able to illustrate my teachings.<br />

Hui!-- He is not stupid.'<br />

CHAP. X. 1. The Master said, 'See what a man does.<br />

2. 'Mark his motives.<br />

3. 'Examine in what things he rests.<br />

4. 'How can a man conceal his character?<br />

5. How can a man conceal his character?'<br />

CHAP. XI. The Master said, 'If a man keeps cherishing his old<br />

knowledge, so as continually to be acquiring new, he may be a<br />

teacher of others.'<br />

CHAP. XII. The Master said, 'The accomplished scholar is not a<br />

utensil.'<br />

CHAP. XIII. Tsze-kung asked what constituted the superior<br />

man. The Master said, 'He acts before he speaks, and afterwards<br />

speaks according to his actions.'<br />

CHAP. XIV. The Master said, 'The superior man is catholic and<br />

no partisan. The mean man is partisan and not catholic.'<br />

CHAP. XV. The Master said, 'Learning without thought is<br />

labour lost; thought without learning is perilous.'<br />

CHAP. XVI. The Master said, 'The study of strange doctrines is<br />

injurious indeed!'<br />

CHAP. XVII. The Master said, 'Yu, shall I teach you what<br />

knowledge is? When you know a thing, to hold that you know it;<br />

and when you do not know a thing, to allow that you do not know<br />

it;-- this is knowledge.'<br />

CHAP. XVII. 1. Tsze-chang was learning with a view to official<br />

emolument.

2. The Master said, 'Hear much and put aside the points of<br />

which you stand in doubt, while you speak cautiously at the same<br />

time of the others:-- then you will afford few occasions for blame.<br />

See much and put aside the things which seem perilous, while you<br />

are cautious at the same time in carrying the others into practice:--<br />

then you will have few occasions for repentance. When one gives<br />

few occasions for blame in his words, and few occasions for<br />

repentance in his conduct, he is in the way to get emolument.'<br />

CHAP. XIX. The Duke Ai asked, saying, 'What should be done<br />

in order to secure the submission of the people?' Confucius replied,<br />

'Advance the upright and set aside the crooked, then the people<br />

will submit. Advance the crooked and set aside the upright, then<br />

the people will not submit.'<br />

CHAP. XX. Chi K'ang asked how to cause the people to<br />

reverence their ruler, to be faithful to him, and to go on to nerve<br />

themselves to virtue. The Master said, 'Let him preside over them<br />

with gravity;-- then they will reverence him. Let him be filial and<br />

kind to all;-- then they will be faithful to him. Let him advance the<br />

good and teach the incompetent;-- then they will eagerly seek to be<br />

virtuous.'<br />

CHAP. XXI. 1. Some one addressed Confucius, saying, 'Sir, why<br />

are you not engaged in the government?'<br />

2. The Master said, 'What does the Shu-ching say of filial<br />

piety?-- "You are filial, you discharge your brotherly duties. These<br />

qualities are displayed in government." This then also constitutes<br />

the exercise of government. Why must there be THAT-- making one<br />

be in the government?'<br />

CHAP. XXII. The Master said, 'I do not know how a man<br />

without truthfulness is to get on. How can a large carriage be made<br />

to go without the cross-bar for yoking the oxen to, or a small<br />

carriage without the arrangement for yoking the horses?'<br />

CHAP. XXIII. 1. Tsze-chang asked whether the affairs of ten<br />

ages after could be known.<br />

2. Confucius said, 'The Yin dynasty followed the regulations of<br />

the Hsia: wherein it took from or added to them may be known. The

Chau dynasty has followed the regulations of Yin: wherein it took<br />

from or added to them may be known. Some other may follow the<br />

Chau, but though it should be at the distance of a hundred ages, its<br />

affairs may be known.'<br />

CHAP. XXIV. 1. The Master said, 'For a man to sacrifice to a<br />

spirit which does not belong to him is flattery.<br />

2. 'To see what is right and not to do it is want of courage.'<br />

BOOK III. PA YIH.<br />

CHAP. I. Confucius said of the head of the Chi family, who had<br />

eight rows of pantomimes in his area, 'If he can bear to do this,<br />

what may he not bear to do?'<br />

CHAP. II. The three families used the YUNG ode, while the<br />

vessels were being removed, at the conclusion of the sacrifice. The<br />

Master said, '"Assisting are the princes;-- the son of heaven looks<br />

profound and grave:"-- what application can these words have in<br />

the hall of the three families?'<br />

CHAP. III. The Master said, 'If a man be without the virtues<br />

proper to humanity, what has he to do with the rites of propriety?<br />

If a man be without the virtues proper to humanity, what has he to<br />

do with music?'<br />

CHAP. IV. 1. Lin Fang asked what was the first thing to be<br />

attended to in ceremonies.<br />

2. The Master said, 'A great question indeed!<br />

3. 'In festive ceremonies, it is better to be sparing than<br />

extravagant.<br />

In the ceremonies of mourning, it is better that there be deep<br />

sorrow than a minute attention to observances.'<br />

CHAP. V. The Master said, 'The rude tribes of the east and<br />

north have their princes, and are not like the States of our great<br />

land which are without them.'<br />

CHAP. VI. The chief of the Chi family was about to sacrifice to<br />

the T'ai mountain. The Master said to Zan Yu, 'Can you not save him

from this?' He answered, 'I cannot.' Confucius said, 'Alas! will you<br />

say that the T'ai mountain is not so discerning as Lin Fang?'<br />

CHAP. VII. The Master said, 'The student of virtue has no<br />

contentions. If it be said he cannot avoid them, shall this be in<br />

archery? But he bows complaisantly to his competitors; thus he<br />

ascends the hall, descends, and exacts the forfeit of drinking. In his<br />

contention, he is still the Chun-tsze.'<br />

CHAP. VIII. 1. Tsze-hsia asked, saying, 'What is the meaning<br />

of the passage-- "The pretty dimples of her artful smile! The welldefined<br />

black and white of her eye! The plain ground for the<br />

colours?"'<br />

2. The Master said, 'The business of laying on the colours<br />

follows (the preparation of) the plain ground.'<br />

3. 'Ceremonies then are a subsequent thing?' The Master said,<br />

'It is Shang who can bring out my meaning. Now I can begin to talk<br />

about the odes with him.'<br />

CHAP. IX. The Master said, 'I could describe the ceremonies of<br />

the Hsia dynasty, but Chi cannot sufficiently attest my words. I<br />

could describe the ceremonies of the Yin dynasty, but Sung cannot<br />

sufficiently attest my words. (They cannot do so) because of the<br />

insufficiency of their records and wise men. If those were<br />

sufficient, I could adduce them in support of my words.'<br />

CHAP. X. The Master said, 'At the great sacrifice, after the<br />

pouring out of the libation, I have no wish to look on.'<br />

CHAP. XI. Some one asked the meaning of the great sacrifice.<br />

The Master said, 'I do not know. He who knew its meaning would<br />

find it as easy to govern the kingdom as to look on this;-- pointing<br />

to his palm.<br />

CHAP. XII. 1. He sacrificed to the dead, as if they were<br />

present. He sacrificed to the spirits, as if the spirits were present.<br />

2. The Master said, 'I consider my not being present at the<br />

sacrifice, as if I did not sacrifice.'<br />

CHAP. XIII. 1. Wang-sun Chia asked, saying, 'What is the

meaning of the saying, "It is better to pay court to the furnace than<br />

to the south-west corner?"'<br />

2. The Master said, 'Not so. He who offends against Heaven<br />

has none to whom he can pray.'<br />

CHAP. XIV. The Master said, 'Chau had the advantage of<br />

viewing the two past dynasties. How complete and elegant are its<br />

regulations! I follow Chau.'<br />

CHAP. XV. The Master, when he entered the grand temple,<br />

asked about everything. Some one said, 'Who will say that the son<br />

of the man of Tsau knows the rules of propriety! He has entered the<br />

grand temple and asks about everything.' The Master heard the<br />

remark, and said, 'This is a rule of propriety.'<br />

CHAP. XVI. The Master said, 'In archery it is not going<br />

through the leather which is the principal thing;-- because people's<br />

strength is not equal. This was the old way.'<br />

CHAP. XVII. 1. Tsze-kung wished to do away with the offering<br />

of a sheep connected with the inauguration of the first day of each<br />

month.<br />

2. The Master said, 'Ts'ze, you love the sheep; I love the<br />

ceremony.'<br />

CHAP. XVII. The Master said, 'The full observance of the rules<br />

of propriety in serving one's prince is accounted by people to be<br />

flattery.'<br />

CHAP. XIX. The Duke Ting asked how a prince should employ<br />

his ministers, and how ministers should serve their prince.<br />

Confucius replied, 'A prince should employ his minister according to<br />

according to the rules of propriety; ministers should serve their<br />

prince with faithfulness.'<br />

CHAP. XX. The Master said, 'The Kwan Tsu is expressive of<br />

enjoyment without being licentious, and of grief without being<br />

hurtfully excessive.'<br />

CHAP. XXI. 1. The Duke Ai asked Tsai Wo about the altars of

the spirits of the land. Tsai Wo replied, 'The Hsia sovereign planted<br />

the pine tree about them; the men of the Yin planted the cypress;<br />

and the men of the Chau planted the chestnut tree, meaning<br />

thereby to cause the people to be in awe.'<br />

2. When the Master heard it, he said, 'Things that are done, it<br />

is needless to speak about; things that have had their course, it is<br />

needless to remonstrate about; things that are past, it is needless to<br />

blame.'<br />

CHAP. XXII. 1. The Master said, 'Small indeed was the capacity<br />

of Kwan Chung!'<br />

2. Some one said, 'Was Kwan Chung parsimonious?' 'Kwan,'<br />

was the reply, 'had the San Kwei, and his officers performed no<br />

double duties; how can he be considered parsimonious?'<br />

3. 'Then, did Kwan Chung know the rules of propriety?' The<br />

Master said, 'The princes of States have a screen intercepting the<br />

view at their gates. Kwan had likewise a screen at his gate. The<br />

princes of States on any friendly meeting between two of them, had<br />

a stand on which to place their inverted cups. Kwan had also such a<br />

stand. If Kwan knew the rules of propriety, who does not know<br />

them?'<br />

CHAP. XXXII. The Master instructing the grand music-master<br />

of Lu said, 'How to play music may be known. At the<br />

commencement of the piece, all the parts should sound together. As<br />

it proceeds, they should be in harmony while severally distinct and<br />

flowing without break, and thus on to the conclusion.'<br />

CHAP. XXIV. The border warden at Yi requested to be<br />

introduced to the Master, saying, 'When men of superior virtue<br />

have come to this, I have never been denied the privilege of seeing<br />

them.' The followers of the sage introduced him, and when he came<br />

out from the interview, he said, 'My friends, why are you distressed<br />

by your master's loss of office? The kingdom has long been without<br />

the principles of truth and right; Heaven is going to use your master<br />

as a bell with its wooden tongue.'<br />

CHAP. XXV. The Master said of the Shao that it was perfectly<br />

beautiful and also perfectly good. He said of the Wu that it was<br />

perfectly beautiful but not perfectly good.

CHAP. XXVI. The Master said, 'High station filled without<br />

indulgent generosity; ceremonies performed without reverence;<br />

mourning conducted without sorrow;-- wherewith should I<br />

contemplate such ways?'<br />

BOOK IV. LE JIN.<br />

CHAP. I. The Master said, 'It is virtuous manners which<br />

constitute the excellence of a neighborhood. If a man in selecting a<br />

residence, do not fix on one where such prevail, how can he be<br />

wise?'<br />

CHAP. II. The Master said, 'Those who are without virtue<br />

cannot abide long either in a condition of poverty and hardship, or<br />

in a condition of enjoyment. The virtuous rest in virtue; the wise<br />

desire virtue.'<br />

CHAP. III. The Master said, 'It is only the (truly) virtuous<br />

man, who can love, or who can hate, others.'<br />

CHAP. IV. The Master said, 'If the will be set on virtue, there<br />

will be no practice of wickedness.'<br />

CHAP. V. 1. The Master said, 'Riches and honours are what<br />

men desire. If it cannot be obtained in the proper way, they should<br />

not be held. Poverty and meanness are what men dislike. If it<br />

cannot be avoided in the proper way, they should not be avoided.<br />

2. 'If a superior man abandon virtue, how can he fulfil the<br />

requirements of that name?<br />

3. 'The superior man does not, even for the space of a single<br />

meal, act contrary to virtue. In moments of haste, he cleaves to it.<br />

In seasons of danger, he cleaves to it.'<br />

CHAP. VI. 1. The Master said, 'I have not seen a person who<br />

loved virtue, or one who hated what was not virtuous. He who<br />

loved virtue, would esteem nothing above it. He who hated what is<br />

not virtuous, would practise virtue in such a way that he would not<br />

allow anything that is not virtuous to approach his person.<br />

2. 'Is any one able for one day to apply his strength to virtue?

I have not seen the case in which his strength would be insufficient.<br />

3. 'Should there possibly be any such case, I have not seen it.'<br />

CHAP. VII. The Master said, 'The faults of men are<br />

characteristic of the class to which they belong. By observing a<br />

man's faults, it may be known that he is virtuous.'<br />

CHAP. VIII. The Master said, 'If a man in the morning hear<br />

the right way, he may die in the evening without regret.'<br />

CHAP. IX. The Master said, 'A scholar, whose mind is set on<br />

truth, and who is ashamed of bad clothes and bad food, is not fit to<br />

be discoursed with.'<br />

CHAP. X. The Master said, 'The superior man, in the world,<br />

does not set his mind either for anything, or against anything; what<br />

is right he will follow.'<br />

CHAP. XI. The Master said, 'The superior man thinks of virtue;<br />

the small man thinks of comfort. The superior man thinks of the<br />

sanctions of law; the small man thinks of favours which he may<br />

receive.'<br />

CHAP. XII. The Master said: 'He who acts with a constant view<br />

to his own advantage will be much murmured against.'<br />

CHAP. XIII. The Master said, 'Is a prince is able to govern his<br />

kingdom with the complaisance proper to the rules of propriety,<br />

what difficulty will he have? If he cannot govern it with that<br />

complaisance, what has he to do with the rules of propriety?'<br />

CHAP. XIV. The Master said, 'A man should say, I am not<br />

concerned that I have no place, I am concerned how I may fit<br />

myself for one. I am not concerned that I am not known, I seek to<br />

be worthy to be known.'<br />

CHAP. XV. 1. The Master said, 'Shan, my doctrine is that of an<br />

all-pervading unity.' The disciple Tsang replied, 'Yes.'<br />

2. The Master went out, and the other disciples asked, saying,<br />

'What do his words mean?' Tsang said, 'The doctrine of our master

is to be true to the principles of our nature and the benevolent<br />

exercise of them to others,-- this and nothing more.'<br />

CHAP. XVI. The Master said, 'The mind of the superior man is<br />

conversant with righteousness; the mind of the mean man is<br />

conversant with gain.'<br />

CHAP. XVII. The Master said, 'When we see men of worth, we<br />

should think of equalling them; when we see men of a contrary<br />

character, we should turn inwards and examine ourselves.'<br />

CHAP. XVIII. The Master said, 'In serving his parents, a son<br />

may remonstrate with them, but gently; when he sees that they do<br />

not incline to follow his advice, he shows an increased degree of<br />

reverence, but does not abandon his purpose; and should they<br />

punish him, he does not allow himself to murmur.'<br />

CHAP. XIX. The Master said, 'While his parents are alive, the<br />

son may not go abroad to a distance. If he does go abroad, he must<br />

have a fixed place to which he goes.'<br />

CHAP. XX. The Master said, 'If the son for three years does not<br />

alter from the way of his father, he may be called filial.'<br />

CHAP. XXI. The Master said, 'The years of parents may by no<br />

means not be kept in the memory, as an occasion at once for joy<br />

and for fear.'<br />

CHAP. XXII. The Master said, 'The reason why the ancients did<br />

not readily give utterance to their words, was that they feared lest<br />

their actions should not come up to them.'<br />

CHAP. XXIII. The Master said, 'The cautious seldom err.'<br />

CHAP. XXIV. The Master said, 'The superior man wishes to be<br />

slow in his speech and earnest in his conduct.'<br />

CHAP. XXV. The Master said, 'Virtue is not left to stand alone.<br />

He who practises it will have neighbors.'

CHAP. XXVI. Tsze-yu said, 'In serving a prince, frequent<br />

remonstrances lead to disgrace. Between friends, frequent reproofs<br />

make the friendship distant.'<br />

BOOK V. KUNG-YE CH'ANG.<br />

CHAP. I. 1. The Master said of Kung-ye Ch'ang that he might<br />

be wived; although he was put in bonds, he had not been guilty of<br />

any crime. Accordingly, he gave him his own daughter to wife.<br />

2. Of Nan Yung he said that if the country were well governed<br />

he would not be out of office, and if it were ill-governed, he would<br />

escape punishment and disgrace. He gave him the daughter of his<br />

own elder brother to wife.<br />

CHAP. II. The Master said of Tsze-chien, 'Of superior virtue<br />

indeed is such a man! If there were not virtuous men in Lu, how<br />

could this man have acquired this character?'<br />

CHAP. III. Tsze-kung asked, 'What do you say of me, Ts'ze?<br />

The Master said, 'You are a utensil.' 'What utensil?' 'A gemmed<br />

sacrificial utensil.'<br />

CHAP. IV. 1. Some one said, 'Yung is truly virtuous, but he is<br />

not ready with his tongue.'<br />

2. The Master said, 'What is the good of being ready with the<br />

tongue? They who encounter men with smartnesses of speech for<br />

the most part procure themselves hatred. I know not whether he<br />

be truly virtuous, but why should he show readiness of the<br />

tongue?'<br />

CHAP. V. The Master was wishing Ch'i-tiao K'ai to enter on<br />

official employment. He replied, 'I am not yet able to rest in the<br />

assurance of THIS.' The Master was pleased.<br />

CHAP. VI. The Master said, 'My doctrines make no way. I will<br />

get upon a raft, and float about on the sea. He that will accompany<br />

me will be Yu, I dare say.' Tsze-lu hearing this was glad,<br />

upon which the Master said, 'Yu is fonder of daring than I am. He<br />

does not exercise his judgment upon matters.'

CHAP. VII. 1. Mang Wu asked about Tsze-lu, whether he was<br />

perfectly virtuous. The Master said, 'I do not know.'<br />

2. He asked again, when the Master replied, 'In a kingdom of<br />

a thousand chariots, Yu might be employed to manage the military<br />

levies, but I do not know whether he be perfectly virtuous.'<br />

3. 'And what do you say of Ch'iu?' The Master replied, 'In a<br />

city of a thousand families, or a clan of a hundred chariots, Ch'iu<br />

might be employed as governor, but I do not know whether he is<br />

perfectly virtuous.'<br />

4. 'What do you say of Ch'ih?' The Master replied, 'With his<br />

sash girt and standing in a court, Ch'ih might be employed to<br />

converse with the visitors and guests, but I do not know whether<br />

he is perfectly virtuous.'<br />

CHAP. VIII. 1. The Master said to Tsze-kung, 'Which do you<br />

consider superior, yourself or Hui?'<br />

2. Tsze-kung replied, 'How dare I compare myself with Hui?<br />

Hui hears one point and knows all about a subject; I hear one point,<br />

and know a second.'<br />

3. The Master said, 'You are not equal to him. I grant you, you<br />

are not equal to him.'<br />

CHAP. IX. 1. Tsai Yu being asleep during the daytime, the<br />

Master said, 'Rotten wood cannot be carved; a wall of dirty earth<br />

will not receive the trowel. This Yu!-- what is the use of my<br />

reproving him?'<br />

2. The Master said, 'At first, my way with men was to hear<br />

their words, and give them credit for their conduct. Now my way is<br />

to hear their words, and look at their conduct. It is from Yu that I<br />

have learned to make this change.'<br />

CHAP. X. The Master said, 'I have not seen a firm and<br />

unbending man.' Some one replied, 'There is Shan Ch'ang.' 'Ch'ang,'<br />

said the Master, 'is under the influence of his passions; how can he<br />

be pronounced firm and unbending?'<br />

CHAP. XI. Tsze-kung said, 'What I do not wish men to do to<br />

me, I also wish not to do to men.' The Master said, 'Ts'ze, you have<br />

not attained to that.'

CHAP. XII. Tsze-kung said, 'The Master's personal displays of<br />

his principles and ordinary descriptions of them may be heard. His<br />

discourses about man's nature, and the way of Heaven, cannot be<br />

heard.'<br />

CHAP. XIII. When Tsze-lu heard anything, if he had not yet<br />

succeeded in carrying it into practice, he was only afraid lest he<br />

should hear something else.<br />

CHAP. XIV. Tsze-kung asked, saying, 'On what ground did<br />

Kung-wan get that title of Wan?' The Master said, 'He was of an<br />

active nature and yet fond of learning, and he was not ashamed to<br />

ask and learn of his inferiors!-- On these grounds he has been<br />

styled Wan.'<br />

CHAP. XV. The Master said of Tsze-ch'an that he had four of<br />

the characteristics of a superior man:-- in his conduct of himself, he<br />

was humble; in serving his superiors, he was respectful; in<br />

nourishing the people, he was kind; in ordering the people, he was<br />

just.'<br />

CHAP. XVI. The Master said, 'Yen P'ing knew well how to<br />

maintain friendly intercourse. The acquaintance might be long, but<br />

he showed the same respect as at first.'<br />

CHAP. XVII. The Master said, 'Tsang Wan kept a large tortoise<br />

in a house, on the capitals of the pillars of which he had hills made,<br />

and with representations of duckweed on the small pillars above<br />

the beams supporting the rafters.-- Of what sort was his wisdom?'<br />

CHAP. XVIII. 1. Tsze-chang asked, saying, 'The minister Tszewan<br />

thrice took office, and manifested no joy in his countenance.<br />

Thrice he retired from office, and manifested no displeasure. He<br />

made it a point to inform the new minister of the way in which he<br />

had conducted the government;-- what do you say of him?' The<br />

Master replied. 'He was loyal.' 'Was he perfectly virtuous?' 'I do not<br />

know. How can he be pronounced perfectly virtuous?'<br />

2. Tsze-chang proceeded, 'When the officer Ch'ui killed the<br />

prince of Ch'i, Ch'an Wan, though he was the owner of forty horses,<br />

abandoned them and left the country. Coming to another State, he

said, "They are here like our great officer, Ch'ui," and left it. He<br />

came to a second State, and with the same observation left it also;--<br />

what do you say of him?' The Master replied, 'He was pure.' 'Was he<br />

perfectly virtuous?' 'I do not know. How can he be pronounced<br />

perfectly virtuous?'<br />

CHAP. XIX. Chi Wan thought thrice, and then acted. When the<br />

Master was informed of it, he said, 'Twice may do.'<br />

CHAP. XX. The Master said, 'When good order prevailed in his<br />

country, Ning Wu acted the part of a wise man. When his country<br />

was in disorder, he acted the part of a stupid man. Others may<br />

equal his wisdom, but they cannot equal his stupidity.'<br />

CHAP. XXI. When the Master was in Ch'an, he said, 'Let me<br />

return! Let me return! The little children of my school are<br />

ambitious and too hasty. They are accomplished and complete so<br />

far, but they do not know how to restrict and shape themselves.'<br />

CHAP. XXII. The Master said, 'Po-i and Shu-ch'i did not keep<br />

the former wickednesses of men in mind, and hence the<br />

resentments directed towards them were few.'<br />

CHAP. XXIII. The Master said, 'Who says of Wei-shang Kao<br />

that he is upright? One begged some vinegar of him, and he begged<br />

it of a neighbor and gave it to the man.'<br />

CHAP. XXIV. The Master said, 'Fine words, an insinuating<br />

appearance, and excessive respect;-- Tso Ch'iu-ming was ashamed<br />

of them. I also am ashamed of them. To conceal resentment against<br />

a person, and appear friendly with him;-- Tso Ch'iu-ming was<br />

ashamed of such conduct. I also am ashamed of it.'<br />

CHAP. XXV. 1. Yen Yuan and Chi Lu being by his side, the<br />

Master said to them, 'Come, let each of you tell his wishes.'<br />

2. Tsze-lu said, 'I should like, having chariots and horses, and<br />

light fur dresses, to share them with my friends, and though they<br />

should spoil them, I would not be displeased.'<br />

3. Yen Yuan said, 'I should like not to boast of my excellence,<br />

nor to make a display of my meritorious deeds.'

4. Tsze-lu then said, 'I should like, sir, to hear your wishes.'<br />

The Master said, 'They are, in regard to the aged, to give them rest;<br />

in regard to friends, to show them sincerity; in regard to the young,<br />

to treat them tenderly.'<br />

CHAP. XXVI. The Master said, 'It is all over! I have not yet<br />

seen one who could perceive his faults, and inwardly accuse<br />

himself.'<br />

CHAP. XXVII. The Master said, 'In a hamlet of ten families,<br />

there may be found one honourable and sincere as I am, but not so<br />

fond of learning.'<br />

BOOK VI. YUNG YEY.<br />

CHAP. I. 1. The Master said, 'There is Yung!-- He might occupy<br />

the place of a prince.'<br />

2. Chung-kung asked about Tsze-sang Po-tsze. The Master<br />

said, 'He may pass. He does not mind small matters.'<br />

3. Chung-kung said, 'If a man cherish in himself a reverential<br />

feeling of the necessity of attention to business, though he may be<br />

easy in small matters in his government of the people, that may be<br />

allowed. But if he cherish in himself that easy feeling, and also<br />

carry it out in his practice, is not such an easy mode of procedure<br />

excessive?'<br />

4. The Master said, 'Yung's words are right.'<br />

CHAP. II. The Duke Ai asked which of the disciples loved to<br />

learn. Confucius replied to him, 'There was Yen Hui; HE loved to<br />

learn. He did not transfer his anger; he did not repeat a fault.<br />

Unfortunately, his appointed time was short and he died; and now<br />

there is not such another. I have not yet heard of any one who<br />

loves to learn as he did.'<br />

CHAP. III. 1. Tsze-hwa being employed on a mission to Ch'i,<br />

the disciple Zan requested grain for his mother. The Master said,<br />

'Give her a fu.' Yen requested more. 'Give her an yu,' said the<br />

Master. Yen gave her five ping.<br />

2. The Master said, 'When Ch'ih was proceeding to Ch'i, he had<br />

fat horses to his carriage, and wore light furs. I have heard that

a superior man helps the distressed, but does not add to the wealth<br />

of the rich.'<br />

3. Yuan Sze being made governor of his town by the Master,<br />

he gave him nine hundred measures of grain, but Sze declined<br />

them.<br />

4. The Master said, 'Do not decline them. May you not give<br />

them away in the neighborhoods, hamlets, towns, and villages?'<br />

CHAP. IV. The Master, speaking of Chung-kung, said, 'If the<br />

calf of a brindled cow be red and horned, although men may not<br />

wish to use it, would the spirits of the mountains and rivers put it<br />

aside?'<br />

CHAP. V. The Master said, 'Such was Hui that for three months<br />

there would be nothing in his mind contrary to perfect virtue. The<br />

others may attain to this on some days or in some months, but<br />

nothing more.'<br />

CHAP. VI. Chi K'ang asked about Chung-yu, whether he was fit<br />

to be employed as an officer of government. The Master said, 'Yu is<br />

a man of decision; what difficulty would he find in being an officer<br />

of government?' K'ang asked, 'Is Ts'ze fit to be employed as an<br />

officer of government?' and was answered, 'Ts'ze is a man of<br />

intelligence; what difficulty would he find in being an officer of<br />

government?' And to the same question about Ch'iu the Master<br />

gave the same reply, saying, 'Ch'iu is a man of various ability.'<br />

CHAP. VII. The chief of the Chi family sent to ask Min Tszech'ien<br />

to be governor of Pi. Min Tsze-ch'ien said, 'Decline the offer<br />

for me politely. If any one come again to me with a second<br />

invitation, I shall be obliged to go and live on the banks of the<br />

Wan.'<br />

CHAP. VIII. Po-niu being ill, the Master went to ask for him.<br />

He took hold of his hand through the window, and said, 'It is killing<br />

him. It is the appointment of Heaven, alas! That such a man should<br />

have such a sickness! That such a man should have such a sickness!'<br />

CHAP. IX. The Master said, 'Admirable indeed was the<br />

virtue of Hui! With a single bamboo dish of rice, a single gourd dish

of drink, and living in his mean narrow lane, while others could not<br />

have endured the distress, he did not allow his joy to be affected by<br />

it. Admirable indeed was the virtue of Hui!'<br />

CHAP. X. Yen Ch'iu said, 'It is not that I do not delight in your<br />

doctrines, but my strength is insufficient.' The Master said, 'Those<br />

whose strength is insufficient give over in the middle of the way<br />

but now you limit yourself.'<br />

CHAP. XI. The Master said to Tsze-hsia, 'Do you be a scholar<br />

after the style of the superior man, and not after that of the mean<br />

man.'<br />

CHAP. XII. Tsze-yu being governor of Wu-ch'ang, the Master<br />

said to him, 'Have you got good men there?' He answered, 'There is<br />

Tan-t'ai Mieh-ming, who never in walking takes a short cut, and<br />

never comes to my office, excepting on public business.'<br />

CHAP. XIII. The Master said, 'Mang Chih-fan does not boast of<br />

his merit. Being in the rear on an occasion of flight, when they were<br />

about to enter the gate, he whipped up his horse, saying, "It is not<br />

that I dare to be last. My horse would not advance."'<br />

CHAP. XIV. The Master said, 'Without the specious speech of<br />

the litanist T'o and the beauty of the prince Chao of Sung, it is<br />

difficult to escape in the present age.'<br />

CHAP. XV. The Master said, 'Who can go out but by the door?<br />

How is it that men will not walk according to these ways?'<br />

CHAP. XVI. The Master said, 'Where the solid qualities are in<br />

excess of accomplishments, we have rusticity; where the<br />

accomplishments are in excess of the solid qualities, we have the<br />

manners of a clerk. When the accomplishments and solid qualities<br />

are equally blended, we then have the man of virtue.'<br />

CHAP. XVII. The Master said, 'Man is born for uprightness. If<br />

a man lose his uprightness, and yet live, his escape from death is<br />

the effect of mere good fortune.'

CHAP. XVIII. The Master said, 'They who know the truth are<br />

not equal to those who love it, and they who love it are not equal to<br />

those who delight in it.'<br />

CHAP. XIX. The Master said, 'To those whose talents are above<br />

mediocrity, the highest subjects may be announced. To those who<br />

are below mediocrity, the highest subjects may not be announced.'<br />

CHAP. XX. Fan Ch'ih asked what constituted wisdom. The<br />

Master said, 'To give one's self earnestly to the duties due to men,<br />

and, while respecting spiritual beings, to keep aloof from them, may<br />

be called wisdom.' He asked about perfect virtue. The Master said,<br />

'The man of virtue makes the difficulty to be overcome his first<br />

business, and success only a subsequent consideration;-- this may<br />

be called perfect virtue.'<br />

CHAP. XXI. The Master said, 'The wise find pleasure in water;<br />

the virtuous find pleasure in hills. The wise are active; the virtuous<br />

are tranquil. The wise are joyful; the virtuous are long-lived.'<br />

CHAP. XXII. The Master said, 'Ch'i, by one change, would come<br />

to the State of Lu. Lu, by one change, would come to a State where<br />

true principles predominated.'<br />

CHAP. XXIII. The Master said, 'A cornered vessel without<br />

corners.-- A strange cornered vessel! A strange cornered vessel!'<br />

CHAP. XXIV. Tsai Wo asked, saying, 'A benevolent man,<br />

though it be told him,-- 'There is a man in the well' will go in after<br />

him, I suppose.' Confucius said, 'Why should he do so?' A superior<br />

man may be made to go to the well, but he cannot be made to go<br />

down into it. He may be imposed upon, but he cannot be fooled.'<br />

CHAP. XXV. The Master said, 'The superior man, extensively<br />

studying all learning, and keeping himself under the restraint of<br />

the rules of propriety, may thus likewise not overstep what is<br />

right.'<br />

CHAP. XXVI. The Master having visited Nan-tsze, Tsze-lu was<br />

displeased, on which the Master swore, saying, 'Wherein I have

done improperly, may Heaven reject me, may Heaven reject me!'<br />

CHAP. XXVII. The Master said, 'Perfect is the virtue which is<br />

according to the Constant Mean! Rare for a long time has been its<br />

practise among the people.'<br />

CHAP. XXVIII. 1. Tsze-kung said, 'Suppose the case of a man<br />

extensively conferring benefits on the people, and able to assist all,<br />

what would you say of him? Might he be called perfectly virtuous?'<br />

The Master said, 'Why speak only of virtue in connexion with him?<br />

Must he not have the qualities of a sage? Even Yao and Shun were<br />

still solicitous about this.<br />

2. 'Now the man of perfect virtue, wishing to be established<br />

himself, seeks also to establish others; wishing to be enlarged<br />

himself, he seeks also to enlarge others.<br />

3. 'To be able to judge of others by what is nigh in ourselves;--<br />

this may be called the art of virtue.'<br />

BOOK VII. SHU R.<br />

CHAP. I. The Master said, 'A transmitter and not a maker,<br />

believing in and loving the ancients, I venture to compare myself<br />

with our old P'ang.'<br />

CHAP. II. The Master said, 'The silent treasuring up of<br />

knowledge; learning without satiety; and instructing others without<br />

being wearied:-- which one of these things belongs to me?'<br />

CHAP. III. The Master said, 'The leaving virtue without proper<br />

cultivation; the not thoroughly discussing what is learned; not being<br />

able to move towards righteousness of which a knowledge is<br />

gained; and not being able to change what is not good:-- these are<br />

the things which occasion me solicitude.'<br />

CHAP. IV. When the Master was unoccupied with business, his<br />

manner was easy, and he looked pleased.<br />

CHAP. V. The Master said, 'Extreme is my decay. For a long<br />

time, I have not dreamed, as I was wont to do, that I saw the duke<br />

of Chau.'

CHAP. VI. 1. The Master said, 'Let the will be set on the path<br />

of duty.<br />

2. 'Let every attainment in what is good be firmly grasped.<br />

3. 'Let perfect virtue be accorded with.<br />

4. 'Let relaxation and enjoyment be found in the polite arts.'<br />

CHAP. VII. The Master said, 'From the man bringing his<br />

bundle of dried flesh for my teaching upwards, I have never<br />

refused instruction to any one.'<br />

CHAP. VIII. The Master said, 'I do not open up the truth to<br />

one who is not eager to get knowledge, nor help out any one who is<br />

not anxious to explain himself. When I have presented one corner<br />

of a subject to any one, and he cannot from it learn the other three,<br />

I do not repeat my lesson.'<br />

CHAP. IX. 1. When the Master was eating by the side of a<br />

mourner, he never ate to the full.<br />

2. He did not sing on the same day in which he had been<br />

weeping.<br />

CHAP. X. 1. The Master said to Yen Yuan, 'When called to<br />

office, to undertake its duties; when not so called, to lie retired;-- it<br />

is only I and you who have attained to this.'<br />

2. Tsze-lu said, 'If you had the conduct of the armies of a<br />

great State, whom would you have to act with you?'<br />

3. The Master said, 'I would not have him to act with me, who<br />

will unarmed attack a tiger, or cross a river without a boat, dying<br />

without any regret. My associate must be the man who proceeds to<br />

action full of solicitude, who is fond of adjusting his plans, and then<br />

carries them into execution.'<br />

CHAP. XI. The Master said, 'If the search for riches is sure to<br />

be successful, though I should become a groom with whip in hand<br />

to get them, I will do so. As the search may not be successful, I will<br />

follow after that which I love.'<br />

CHAP. XII. The things in reference to which the Master<br />

exercised the greatest caution were -- fasting, war, and sickness.

CHAP. XIII. When the Master was in Ch'i, he heard the Shao,<br />

and for three months did not know the taste of flesh. 'I did not<br />

think'' he said, 'that music could have been made so excellent as<br />

this.'<br />

CHAP. XIV. 1. Yen Yu said, 'Is our Master for the ruler of<br />

Wei?' Tsze-kung said, 'Oh! I will ask him.'<br />

2. He went in accordingly, and said, 'What sort of men were<br />

Po-i and Shu-ch'i?' 'They were ancient worthies,' said the Master.<br />

'Did they have any repinings because of their course?' The Master<br />

again replied, 'They sought to act virtuously, and they did so; what<br />

was there for them to repine about?' On this, Tsze-kung went out<br />

and said, 'Our Master is not for him.'<br />

CHAP. XV. The Master said, 'With coarse rice to eat, with<br />

water to drink, and my bended arm for a pillow;-- I have still joy in<br />

the midst of these things. Riches and honours acquired by<br />

unrighteousness, are to me as a floating cloud.'<br />

CHAP. XVI. The Master said, 'If some years were added to my<br />

life, I would give fifty to the study of the Yi, and then I might come<br />

to be without great faults.'<br />

CHAP. XVII The Master's frequent themes of discourse were--<br />

the Odes, the History, and the maintenance of the Rules of<br />

Propriety. On all these he frequently discoursed.<br />

CHAP. XVIII. 1. The Duke of Sheh asked Tsze-lu about<br />

Confucius, and Tsze-lu did not answer him.<br />

2. The Master said, 'Why did you not say to him,-- He is<br />

simply a man, who in his eager pursuit (of knowledge) forgets his<br />

food, who in the joy of its attainment forgets his sorrows, and who<br />

does not perceive that old age is coming on?'<br />

CHAP. XIX. The Master said, 'I am not one who was born in<br />

the possession of knowledge; I am one who is fond of antiquity, and<br />

earnest in seeking it there.'<br />

CHAP. XX. The subjects on which the Master did not talk,

were-- extraordinary things, feats of strength, disorder, and<br />

spiritual beings.<br />

CHAP. XXI. The Master said, 'When I walk along with two<br />

others, they may serve me as my teachers. I will select their good<br />

qualities and follow them, their bad qualities and avoid them.'<br />

CHAP. XXII. The Master said, 'Heaven produced the virtue<br />

that is in me. Hwan T'ui-- what can he do to me?'<br />

CHAP. XXIII. The Master said, 'Do you think, my disciples, that<br />

I have any concealments? I conceal nothing from you. There is<br />

nothing which I do that is not shown to you, my disciples;-- that is<br />

my way.'<br />

CHAP. XXIV. There were four things which the Master<br />

taught,-- letters, ethics, devotion of soul, and truthfulness.<br />

CHAP. XXV. 1. The Master said, 'A sage it is not mine to see;<br />

could I see a man of real talent and virtue, that would satisfy me.'<br />

2. The Master said, 'A good man it is not mine to see; could I<br />

see a man possessed of constancy, that would satisfy me.<br />

3. 'Having not and yet affecting to have, empty and yet<br />

affecting to be full, straitened and yet affecting to be at ease:-- it is<br />

difficult with such characteristics to have constancy.'<br />

CHAP. XXVI. The Master angled,-- but did not use a net. He<br />

shot,-- but not at birds perching.<br />

CHAP. XXVII. The Master said, 'There may be those who act<br />

without knowing why. I do not do so. Hearing much and selecting<br />

what is good and following it; seeing much and keeping it in<br />

memory:-- this is the second style of knowledge.'<br />

CHAP. XXVIII. 1. It was difficult to talk (profitably and<br />

reputably) with the people of Hu-hsiang, and a lad of that place<br />

having had an interview with the Master, the disciples doubted.<br />

2. The Master said, 'I admit people's approach to me without<br />

committing myself as to what they may do when they have retired.<br />

Why must one be so severe? If a man purify himself to wait upon

me, I receive him so purified, without guaranteeing his past<br />

conduct.'<br />

CHAP. XXIX. The Master said, 'Is virtue a thing remote? I wish<br />

to be virtuous, and lo! virtue is at hand.'<br />

CHAP. XXX. 1. The minister of crime of Ch'an asked whether<br />

the duke Chao knew propriety, and Confucius said, 'He knew<br />

propriety.'<br />

2. Confucius having retired, the minister bowed to Wu-ma Ch'i<br />

to come forward, and said, 'I have heard that the superior man is<br />

not a partisan. May the superior man be a partisan also? The prince<br />

married a daughter of the house of Wu, of the same surname with<br />

himself, and called her,-- "The elder Tsze of Wu." If the prince<br />

knew propriety, who does not know it?'<br />

3. Wu-ma Ch'i reported these remarks, and the Master said, 'I<br />

am fortunate! If I have any errors, people are sure to know them.'<br />

CHAP. XXXI. When the Master was in company with a person<br />

who was singing, if he sang well, he would make him repeat the<br />

song, while he accompanied it with his own voice.<br />

CHAP. XXXII. The Master said, 'In letters I am perhaps equal<br />

to other men, but the character of the superior man, carrying out in<br />

his conduct what he professes, is what I have not yet attained to.'<br />

CHAP. XXXIII. The Master said, 'The sage and the man of<br />

perfect virtue;-- how dare I rank myself with them? It may simply<br />

be said of me, that I strive to become such without satiety, and<br />

teach others without weariness.' Kung-hsi Hwa said, 'This is just<br />

what we, the disciples, cannot imitate you in.'<br />

CHAP. XXXIV. The Master being very sick, Tsze-lu asked leave<br />

to pray for him. He said, 'May such a thing be done?' Tsze-lu<br />

replied, 'It may. In the Eulogies it is said, "Prayer has been made<br />

for thee to the spirits of the upper and lower worlds."' The Master<br />

said, 'My praying has been for a long time.'<br />

CHAP. XXXV. The Master said, 'Extravagance leads to<br />

insubordination, and parsimony to meanness. It is better to be

mean than to be insubordinate.'<br />

CHAP. XXXVI. The Master said, 'The superior man is satisfied<br />

and composed; the mean man is always full of distress.'<br />

CHAP. XXXVII. The Master was mild, and yet dignified;<br />

majestic, and yet not fierce; respectful, and yet easy.<br />

BOOK VIII. T'AI-PO.<br />

CHAP. I. The Master said, 'T'ai-po may be said to have<br />

reached the highest point of virtuous action. Thrice he declined the<br />

kingdom, and the people in ignorance of his motives could not<br />

express their approbation of his conduct.'<br />

CHAP. II. 1. The Master said, 'Respectfulness, without the<br />

rules of propriety, becomes laborious bustle; carefulness, without<br />

the rules of propriety, becomes timidity; boldness, without the rules<br />

of propriety, becomes insubordination; straightforwardness,<br />

without the rules of propriety, becomes rudeness.<br />

2. 'When those who are in high stations perform well all their<br />

duties to their relations, the people are aroused to virtue. When old<br />

friends are not neglected by them, the people are preserved from<br />

meanness.'<br />

CHAP. III. The philosopher Tsang being ill, he called to him<br />

the disciples of his school, and said, 'Uncover my feet, uncover my<br />

hands. It is said in the Book of Poetry, "We should be apprehensive<br />

and cautious, as if on the brink of a deep gulf, as if treading on thin<br />

ice," and so have I been. Now and hereafter, I know my escape<br />

from all injury to my person, O ye, my little children.'<br />

CHAP. IV. 1. The philosopher Tsang being ill, Meng Chang<br />

went to ask how he was.<br />

2. Tsang said to him, 'When a bird is about to die, its notes are<br />

mournful; when a man is about to die, his words are good.<br />

3. 'There are three principles of conduct which the man of<br />

high rank should consider specially important:-- that in his<br />

deportment and manner he keep from violence and heedlessness;<br />

that in regulating his countenance he keep near to sincerity; and

that in his words and tones he keep far from lowness and<br />

impropriety. As to such matters as attending to the sacrificial<br />

vessels, there are the proper officers for them.'<br />

CHAP. V. The philosopher Tsang said, 'Gifted with ability, and<br />

yet putting questions to those who were not so; possessed of much,<br />

and yet putting questions to those possessed of little; having, as<br />

though he had not; full, and yet counting himself as empty;<br />

offended against, and yet entering into no altercation; formerly I<br />

had a friend who pursued this style of conduct.'<br />

CHAP. VI. The philosopher Tsang said, 'Suppose that there is<br />

an individual who can be entrusted with the charge of a young<br />

orphan prince, and can be commissioned with authority over a state<br />

of a hundred li, and whom no emergency however great can drive<br />

from his principles:-- is such a man a superior man? He is a<br />

superior man indeed.'<br />

CHAP. VII. 1. The philosopher Tsang said, 'The officer may not<br />

be without breadth of mind and vigorous endurance. His burden is<br />

heavy and his course is long.<br />

2. 'Perfect virtue is the burden which he considers it is his to<br />

sustain;-- is it not heavy? Only with death does his course stop;-- is<br />

it not long?<br />

CHAP. VIII. 1. The Master said, 'It is by the Odes that the<br />

mind is aroused.<br />

2. 'It is by the Rules of Propriety that the character is<br />

established.<br />

3. 'It is from Music that the finish is received.'<br />

CHAP. IX. The Master said, 'The people may be made to follow<br />

a path of action, but they may not be made to understand it.'<br />

CHAP. X. The Master said, 'The man who is fond of daring and<br />

is dissatisfied with poverty, will proceed to insubordination. So will<br />

the man who is not virtuous, when you carry your dislike of him to<br />

an extreme.'<br />

CHAP. XI. The Master said, 'Though a man have abilities as

admirable as those of the Duke of Chau, yet if he be proud and<br />

niggardly, those other things are really not worth being looked at.'<br />

CHAP. XII. The Master said, 'It is not easy to find a man who<br />

has learned for three years without coming to be good.'<br />

CHAP. XIII. 1. The Master said, 'With sincere faith he unites<br />

the love of learning; holding firm to death, he is perfecting the<br />

excellence of his course.<br />

2. 'Such an one will not enter a tottering State, nor dwell in a<br />

disorganized one. When right principles of government prevail in<br />

the kingdom, he will show himself; when they are prostrated, he<br />

will keep concealed.<br />

3. 'When a country is well-governed, poverty and a mean<br />

condition are things to be ashamed of. When a country is illgoverned,<br />

riches and honour are things to be ashamed of.'<br />

CHAP. XIV. The Master said, 'He who is not in any particular<br />

office, has nothing to do with plans for the administration of its<br />

duties.'<br />

CHAP. XV. The Master said, 'When the music master Chih first<br />

entered on his office, the finish of the Kwan Tsu was magnificent;--<br />

how it filled the ears!'<br />

CHAP. XVI. The Master said, 'Ardent and yet not upright;<br />

stupid and yet not attentive; simple and yet not sincere:-- such<br />

persons I do not understand.'<br />

CHAP. XVII. The Master said, 'Learn as if you could not reach<br />

your object, and were always fearing also lest you should lose it.'<br />

CHAP. XVIII. The Master said, 'How majestic was the manner<br />

in which Shun and Yu held possession of the empire, as if it were<br />

nothing to them!'<br />

CHAP. XIX. 1. The Master said, 'Great indeed was Yao as a<br />

sovereign! How majestic was he! It is only Heaven that is grand,<br />

and only Yao corresponded to it. How vast was his virtue! The<br />

people could find no name for it.

2. 'How majestic was he in the works which he accomplished!<br />

How glorious in the elegant regulations which he instituted!'<br />

CHAP. XX. 1. Shun had five ministers, and the empire was<br />

well-governed.<br />

2. King Wu said, 'I have ten able ministers.'<br />

3. Confucius said, 'Is not the saying that talents are difficult to<br />

find, true? Only when the dynasties of T'ang and Yu met, were they<br />

more abundant than in this of Chau, yet there was a woman among<br />

them. The able ministers were no more than nine men.<br />

4. 'King Wan possessed two of the three parts of the empire,<br />

and with those he served the dynasty of Yin. The virtue of the<br />

house of Chau may be said to have reached the highest point<br />

indeed.'<br />

CHAP. XXI. The Master said, 'I can find no flaw in the<br />

character of Yu. He used himself coarse food and drink, but<br />

displayed the utmost filial piety towards the spirits. His ordinary<br />

garments were poor, but he displayed the utmost elegance in his<br />

sacrificial cap and apron. He lived in a low mean house, but<br />

expended all his strength on the ditches and water-channels. I can<br />

find nothing like a flaw in Yu.'<br />

BOOK IX. TSZE HAN.<br />

CHAP. I. The subjects of which the Master seldom spoke<br />

were-- profitableness, and also the appointments of Heaven, and<br />

perfect virtue.<br />

CHAP. II. 1. A man of the village of Ta-hsiang said, 'Great<br />

indeed is the philosopher K'ung! His learning is extensive, and yet<br />

he does not render his name famous by any particular thing.'<br />

2. The Master heard the observation, and said to his disciples,<br />

'What shall I practise? Shall I practise charioteering, or shall I<br />

practise archery? I will practise charioteering.'<br />

CHAP. III. 1. The Master said, 'The linen cap is that prescribed<br />

by the rules of ceremony, but now a silk one is worn. It is<br />

economical, and I follow the common practice.<br />

2. 'The rules of ceremony prescribe the bowing below the hall,

ut now the practice is to bow only after ascending it. That is<br />

arrogant. I continue to bow below the hall, though I oppose the<br />

common practice.'<br />

CHAP. IV. There were four things from which the Master was<br />

entirely free. He had no foregone conclusions, no arbitrary<br />

predeterminations, no obstinacy, and no egoism.<br />

CHAP. V. 1. The Master was put in fear in K'wang.<br />

2. He said, 'After the death of King Wan, was not the cause of<br />

truth lodged here in me?<br />

3. 'If Heaven had wished to let this cause of truth perish, then<br />

I, a future mortal, should not have got such a relation to that cause.<br />

While Heaven does not let the cause of truth perish, what can the<br />

people of K'wang do to me?'<br />

CHAP. VI. 1. A high officer asked Tsze-kung, saying, 'May we<br />

not say that your Master is a sage? How various is his ability!'<br />

2. Tsze-kung said, 'Certainly Heaven has endowed him<br />

unlimitedly. He is about a sage. And, moreover, his ability is<br />

various.'<br />

3. The Master heard of the conversation and said, 'Does the<br />

high officer know me? When I was young, my condition was low,<br />

and therefore I acquired my ability in many things, but they were<br />

mean matters. Must the superior man have such variety of ability?<br />

He does not need variety of ability.'<br />

4. Lao said, 'The Master said, "Having no official employment,<br />

I acquired many arts."'<br />

CHAP. VII. The Master said, 'Am I indeed possessed of<br />

knowledge? I am not knowing. But if a mean person, who appears<br />

quite empty-like, ask anything of me, I set it forth from one end to<br />

the other, and exhaust it.'<br />

CHAP. VIII. The Master said, 'The FANG bird does not come;<br />

the river sends forth no map:-- it is all over with me!'<br />

CHAP. IX. When the Master saw a person in a mourning dress,<br />

or any one with the cap and upper and lower garments of full<br />

dress, or a blind person, on observing them approaching, though

they were younger than himself, he would rise up, and if he had to<br />

pass by them, he would do so hastily.<br />

CHAP. X. 1. Yen Yuan, in admiration of the Master's doctrines,<br />

sighed and said, 'I looked up to them, and they seemed to become<br />

more high; I tried to penetrate them, and they seemed to become<br />

more firm; I looked at them before me, and suddenly they seemed<br />

to be behind.<br />

2. 'The Master, by orderly method, skilfully leads men on. He<br />

enlarged my mind with learning, and taught me the restraints of<br />

propriety.<br />

3. 'When I wish to give over the study of his doctrines, I<br />

cannot do so, and having exerted all my ability, there seems<br />

something to stand right up before me; but though I wish to follow<br />

and lay hold of it, I really find no way to do so.'<br />

CHAP. XI. 1. The Master being very ill, Tsze-lu wished the<br />

disciples to act as ministers to him.<br />

2. During a remission of his illness, he said, 'Long has the<br />

conduct of Yu been deceitful! By pretending to have ministers when<br />

I have them not, whom should I impose upon? Should I impose<br />

upon Heaven?<br />

3. 'Moreover, than that I should die in the hands of ministers,<br />

is it not better that I should die in the hands of you, my disciples?<br />

And though I may not get a great burial, shall I die upon the road?'<br />

CHAP. XII. Tsze-kung said, 'There is a beautiful gem here.<br />

Should I lay it up in a case and keep it? or should I seek for a good<br />

price and sell it?' The Master said, 'Sell it! Sell it! But I would wait<br />

for one to offer the price.'<br />

CHAP. XIII. 1. The Master was wishing to go and live among<br />

the nine wild tribes of the east.<br />

2. Some one said, 'They are rude. How can you do such a<br />

thing?' The Master said, 'If a superior man dwelt among them, what<br />

rudeness would there be?'<br />

CHAP. XIV. The Master said, 'I returned from Wei to Lu, and<br />

then the music was reformed, and the pieces in the Royal songs and<br />

Praise songs all found their proper places.'

CHAP. XV. The Master said, 'Abroad, to serve the high<br />

ministers and nobles; at home, to serve one's father and elder<br />

brothers; in all duties to the dead, not to dare not to exert one's self;<br />

and not to be overcome of wine:-- which one of these things do I<br />

attain to?'<br />

CHAP. XVI. The Master standing by a stream, said, 'It passes<br />

on just like this, not ceasing day or night!'<br />

CHAP. XVII. The Master said, 'I have not seen one who loves<br />

virtue as he loves beauty.'<br />

CHAP. XVIII. The Master said, 'The prosecution of learning<br />

may be compared to what may happen in raising a mound. If there<br />

want but one basket of earth to complete the work, and I stop, the<br />

stopping is my own work. It may be compared to throwing down<br />

the earth on the level ground. Though but one basketful is thrown<br />

at a time, the advancing with it is my own going forward.'<br />

CHAP. XIX. The Master said, 'Never flagging when I set forth<br />

anything to him;-- ah! that is Hui.'<br />

CHAP. XX. The Master said of Yen Yuan, 'Alas! I saw his<br />

constant advance. I never saw him stop in his progress.'<br />

CHAP. XXI. The Master said, 'There are cases in which the<br />

blade springs, but the plant does not go on to flower! There are<br />

cases where it flowers, but no fruit is subsequently produced!'<br />

CHAP. XXII. The Master said, 'A youth is to be regarded with<br />

respect. How do we know that his future will not be equal to our<br />

present? If he reach the age of forty or fifty, and has not made<br />

himself heard of, then indeed he will not be worth being regarded<br />

with respect.'<br />

CHAP. XXV. The Master said, 'Can men refuse to assent to the<br />

words of strict admonition? But it is reforming the conduct because<br />

of them which is valuable. Can men refuse to be pleased with words<br />

of gentle advice? But it is unfolding their aim which is valuable. If a

man be pleased with these words, but does not unfold their aim,<br />

and assents to those, but does not reform his conduct, I can really<br />

do nothing with him.'<br />

CHAP. XXIV. The Master said, 'Hold faithfulness and sincerity<br />

as first principles. Have no friends not equal to yourself. When you<br />

have faults, do not fear to abandon them.'<br />

CHAP. XXV. The Master said, 'The commander of the forces of<br />

a large state may be carried off, but the will of even a common man<br />

cannot be taken from him.'<br />

CHAP. XXVI. 1. The Master said, 'Dressed himself in a tattered<br />

robe quilted with hemp, yet standing by the side of men dressed in<br />

furs, and not ashamed;-- ah! it is Yu who is equal to this!<br />

2. '"He dislikes none, he covets nothing;-- what can he do but<br />

what is good!"'<br />

3. Tsze-lu kept continually repeating these words of the ode,<br />

when the Master said, 'Those things are by no means sufficient to<br />

constitute (perfect) excellence.'<br />

CHAP. XXVII. The Master said, 'When the year becomes cold,<br />

then we know how the pine and the cypress are the last to lose<br />

their leaves.'<br />

CHAP. XXVIII. The Master said, 'The wise are free from<br />

perplexities; the virtuous from anxiety; and the bold from fear.'<br />

CHAP. XXIX. The Master said, 'There are some with whom we<br />

may study in common, but we shall find them unable to go along<br />

with us to principles. Perhaps we may go on with them to<br />

principles, but we shall find them unable to get established in those<br />

along with us. Or if we may get so established along with them, we<br />

shall find them unable to weigh occurring events along with us.'<br />

CHAP. XXX. 1. How the flowers of the aspen-plum flutter and<br />

turn! Do I not think of you? But your house is distant.<br />

2. The Master said, 'It is the want of thought about it. How is<br />

it distant?'

BOOK X. HEANG TANG.<br />

CHAP. I. 1. Confucius, in his village, looked simple and sincere,<br />

and as if he were not able to speak.<br />

2. When he was in the prince's ancestorial temple, or in the<br />

court, he spoke minutely on every point, but cautiously.<br />

CHAP II. 1. When he was waiting at court, in speaking with<br />

the great officers of the lower grade, he spake freely, but in a<br />

straightforward manner; in speaking with those of the higher grade,<br />

he did so blandly, but precisely.<br />

2. When the ruler was present, his manner displayed<br />

respectful uneasiness; it was grave, but self-possessed.<br />

CHAP. III. 1. When the prince called him to employ him in the<br />

reception of a visitor, his countenance appeared to change, and his<br />

legs to move forward with difficulty.<br />

2. He inclined himself to the other officers among whom he<br />

stood, moving his left or right arm, as their position required, but<br />

keeping the skirts of his robe before and behind evenly adjusted.<br />

3. He hastened forward, with his arms like the wings of a<br />

bird.<br />

4. When the guest had retired, he would report to the prince,<br />

'The visitor is not turning round any more.'<br />

CHAP. IV. 1. When he entered the palace gate, he seemed to<br />

bend his body, as if it were not sufficient to admit him.<br />

2. When he was standing, he did not occupy the middle of the<br />

gate-way; when he passed in or out, he did not tread upon the<br />

threshold.<br />

3. When he was passing the vacant place of the prince, his<br />

countenance appeared to change, and his legs to bend under him,<br />

and his words came as if he hardly had breath to utter them.<br />

4. He ascended the reception hall, holding up his robe with<br />

both his hands, and his body bent; holding in his breath also, as if<br />

he dared not breathe.<br />

5. When he came out from the audience, as soon as he had<br />

descended one step, he began to relax his countenance, and had a<br />

satisfied look. When he had got to the bottom of the steps, he<br />

advanced rapidly to his place, with his arms like wings, and on

occupying it, his manner still showed respectful uneasiness.<br />

CHAP. V. 1. When he was carrying the scepter of his ruler, he<br />

seemed to bend his body, as if he were not able to bear its weight.<br />

He did not hold it higher than the position of the hands in making<br />

a bow, nor lower than their position in giving anything to another.<br />

His countenance seemed to change, and look apprehensive, and he<br />

dragged his feet along as if they were held by something to the<br />

ground.<br />

2. In presenting the presents with which he was charged, he<br />

wore a placid appearance.<br />

3. At his private audience, he looked highly pleased.<br />

CHAP. VI. 1. The superior man did not use a deep purple, or a<br />

puce colour, in the ornaments of his dress.<br />

2. Even in his undress, he did not wear anything of a red or<br />

reddish colour.<br />

3. In warm weather, he had a single garment either of coarse<br />

or fine texture, but he wore it displayed over an inner garment.<br />

4. Over lamb's fur he wore a garment of black; over fawn's fur<br />

one of white; and over fox's fur one of yellow.<br />

5. The fur robe of his undress was long, with the right sleeve<br />

short.<br />

6. He required his sleeping dress to be half as long again as<br />

his body.<br />

7. When staying at home, he used thick furs of the fox or the<br />

badger.<br />

8. When he put off mourning, he wore all the appendages of<br />

the girdle.<br />

9. His under-garment, except when it was required to be of<br />

the curtain shape, was made of silk cut narrow above and wide<br />

below.<br />

10. He did not wear lamb's fur or a black cap, on a visit of<br />

condolence.<br />

11. On the first day of the month he put on his court robes,<br />

and presented himself at court.<br />

CHAP. VII. 1. When fasting, he thought it necessary to have<br />

his clothes brightly clean and made of linen cloth.<br />

2. When fasting, he thought it necessary to change his food,

and also to change the place where he commonly sat in the<br />

apartment.<br />

CHAP. VIII. 1. He did not dislike to have his rice finely<br />

cleaned, nor to have his minced meat cut quite small.<br />