Advertisement

Review

A film critic reflects on Quentin Tarantino's film reflections

When someone once asked Pauline Kael if she wanted to write her memoirs, the legendary critic replied, “I think I already have.” There’s a lot of talk these days in annoying internet circles about objectivity in film reviews, as if anything so intimate as one’s response to a movie could be remotely objective. We bring everything of ourselves into the auditorium with us, all our personal histories and peccadillos are reflected in how we react to what’s up there on the screen. If you read a critic for long enough — assuming they’re any good at their job — you’ll inevitably get a sense of their personality and probably also their pet peeves. We’re here not to offer unbiased decrees but rather informed opinion and analysis. Try as we might, it’s impossible to keep ourselves out of the assignment. (Though admittedly, there are writers I wish would try a little harder on that front.) Roger Ebert was fond of quoting author Robert Warshow’s edict: “A man goes to the movies. The critic must be honest enough to admit he is that man.”

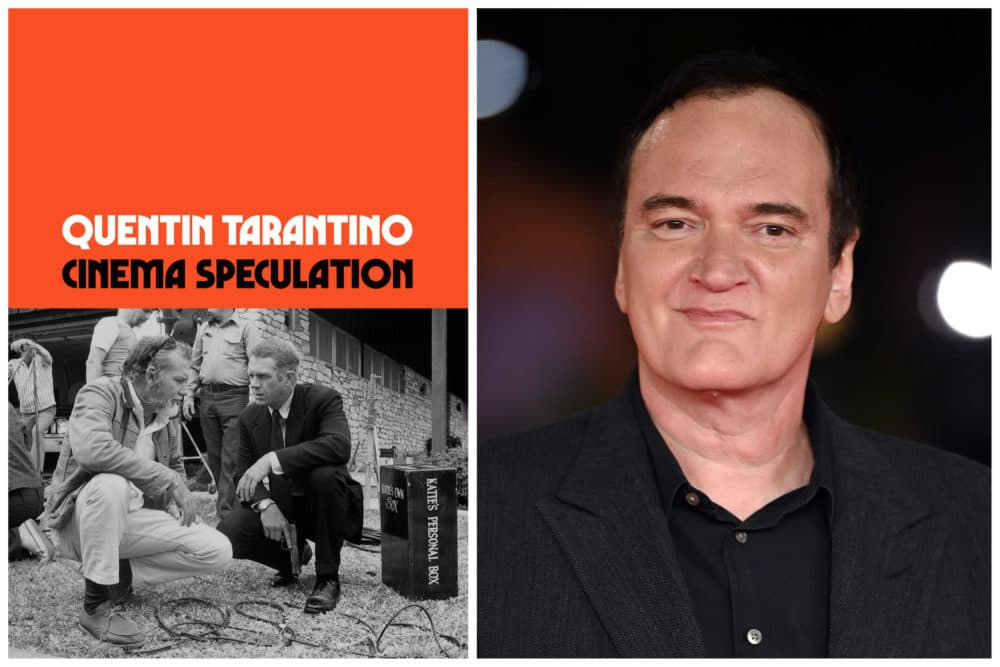

Quentin Tarantino’s “Cinema Speculation” — the writer-director’s first published collection of film criticism (out now) — is a hefty, 370-page volume blurring the lines between analysis and autobiography. It’s basically everything you’d hoped for and everything you’d feared from a book of movie reviews by the former video store clerk who grew up to become one of our greatest living filmmakers. Argumentative, insightful, obnoxious and powered by a compulsively readable passion, the book zooms in on formative films from Tarantino’s childhood, which happened to coincide with an astonishingly fertile period for American cinema.

Thus, we begin with tales like a 9-year-old Quentin being brought by his mother and stepfather to a double feature of “Deliverance” and “The Wild Bunch.” (You don’t have to be a child psychologist to surmise that this evening explains pretty much everything that has followed.) The book is full of well-researched Hollywood history and juicy, behind-the-scenes gossip the author says he heard straight from the horses’ mouths. Reading “Cinema Speculation,” you learn a lot about some seminal films from the 1970s. You learn even more about Quentin Tarantino.

It’s basically everything you’d hoped for and everything you’d feared from a book of movie reviews by the former video store clerk who grew up to become one of our greatest living filmmakers.

The closest thing I’ve ever seen to a superhero origin story for a filmmaker is Tarantino’s rapturous recollection of his mom’s football player boyfriend Reggie bringing him to a downtown LA grindhouse to see Jim Brown in “Black Gunn” on a sold-out Saturday night in 1972. The poorly-programmed double feature paired it with a starchy social issues drama that 850 patrons profanely heckled and booed off the screen, much to the delight of the only white kid in the room. Tarantino describes the experience in quasi-religious terms, detailing the audience’s ecstatic, foulmouthed celebration of Brown’s blaxploitation heroics as “the most masculine experience I’d ever been a part of.”

This story might be the skeleton key to Tarantino’s entire cinematic sensibility, explaining not just his obsession with performative Black machismo but also the knee-jerk dismissal of earnest message movies and his almost savant-like understanding of how to work over a crowd. (I don’t know if you’ve seen “Pulp Fiction” with an audience lately, but I try to go every time it comes around. No matter how familiar, the movie remains such an exquisitely timed exercise in tension and release that a packed screening at the Somerville Theatre this past April was louder than a roller-coaster.)

The audience is an omnipresent component of Tarantino’s film reviews. He’s fascinated by the mechanics of how movies work and more importantly, how they work on us. Breaking down controversial button-pushers like “Deliverance” and “Dirty Harry,” he’s incredibly astute about the skill with which these pictures or directors like Sam Peckinpah and Brian De Palma manipulate our lizard-brain reactions. But with the exception of a spirited defense of his pal Peter Bogdanovich’s much-maligned “Daisy Miller,” the book explores this rich and varied era of American films almost exclusively through violent action movies. A massive chunk is devoted to what the writer calls “revengeamatics,” lavishing attention on “Death Wish”-era fantasies of retribution and rather obtusely misreading Martin Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver” as a part of this genre rather than a viscerally conflicted indictment of it. It’s here that the book becomes wearying, with a flabby midsection weighed down by weird repetitions, typos and a criminal abuse of italics.

Tarantino has a voracious appetite for cinema but it is by no means a boundless one, existing within sharply circumscribed parameters of genre and exploitation movies.

Tarantino has a voracious appetite for cinema but it is by no means a boundless one, existing within sharply circumscribed parameters of genre and exploitation movies. His disdain for anything that could be perceived as highfalutin or hoity-toity starts to feel awfully limiting over the long haul of “Cinema Speculation.” The author lobs grenades at artsier efforts like “The Friends of Eddie Coyle” and John Boorman’s psychedelic masterpiece “Point Blank” for being crime pictures that dared act above their station. He gets especially tripped up by the Paul Schrader-penned vigilante trio of “Hardcore,” “Rolling Thunder” and the aforementioned “Taxi Driver,” coming to the conclusion that Schrader can’t write genre screenplays, as if that were ever the intention in the first place. Reading the book makes you realize what it must be like to live on a diet entirely of cheeseburgers, leaving you wishing that Quentin might try a salad once in a while.

The best chapter of “Cinema Speculation” is his generous appreciation of Los Angeles Times critic Kevin Thomas, who for decades dutifully covered all the low-budget independent and exploitation movies that the big shots at the paper didn’t want to bother watching. Paying tribute to the “Second-String Samurai,” Tarantino reprints Thomas’ review of the early Jonathan Demme women-in-prison picture “Caged Heat,” saluting the writer’s palpable thrill of discovery, that excitement of sharing something special you’ve found with others that is the heart of what we do. Tarantino has always been one of our great film evangelists. (Other directors have movie theaters in their mansions. He bought the New Beverly Cinema and screens his personal print collection there for the public.) Annoying as it might sometimes be, his book is bristling with that kind of energy. It's got the inexhaustible verve of someone who just saw a great movie and can’t shut up about it.

There’s a perception that critics get into this racket because we love to tear things down. Believe it or not, it’s actually the opposite. Every writer I know worth a damn wants to spread the word about what we love, inviting others to enjoy a little bit of magic we discovered in the dark. Tarantino says that Kevin Thomas was the only critic at the Times who seemed to enjoy his job. For all its frustrations, wrestling with “Cinema Speculation” reminded me why I love mine.