Sean Scully on self-belief, election billboards and the perils of rural Germany

Ahead of a major retrospective at the Hungarian National Gallery, Irish abstract artist Sean Scully reflects on six decades of redefining abstraction and doing ‘the biggest stretch in the history of the art world’

It’s early September and a plague of flies has just descended on a farm in Mooseurach, Germany where Sean Scully has a studio. ‘A fucking fly bit the middle of my tattoo out’, says the artist over FaceTime, pointing at his forearm towards the now-dismembered Celtic symbol for fertility.

An interview with Sean Scully is like a portrait sitting with a sitter that needs little direction. He describes his life and work in a quilt of similes and anecdotes stitched together with warmth and wit: his coarse upbringing, familial fondness, traumas, brushes with US politics, fervent spirituality, those he admires – from Agnes Martin to Tess Jaray and Béla Bartók – and vibrantly hued recollections of his rise to become ‘the token of abstraction.’

Scully, as he says, came from abject poverty. ‘I probably did the biggest stretch in the history of the art world’ declares the 75-year-old artist. He’s been an immigrant twice: once when he moved from Ireland in 1949 to London, and again when he transfered to New York in 1975. Before breaking into art, he was a brick cleaner on a building site, a Christmas postman, a plasterer’s labourer and had a job stacking cardboard boxes in a factory. Fitting, perhaps, that stacks and bricklike forms would provide the building blocks for Scully’s inimitable visual language.

Portrait of Sean Scully taken in Mooseurach, October 2020. Photography: Liliane Tomasko

In the 1970s, Scully’s paintings sought to fuse American Minimalism and Op Art, which culminated in ‘supergrids’, stripes and blocks of colour. By 1980, the artist was ‘at war’ with Minimalism and instead focussed on what he thought painting should be doing: concentrating on human nature.

When he moved to New York, he knew not everyone would be waiting with open arms. ‘I was welcomed by many; I was also un-welcomed by many,’ he says. ‘I had a lot of detractors in New York.’ Among his ‘defenders’, however, was the art critic Arthur Danto, who insisted that Scully belonged ‘on the shortest of the shortlists of major painters of our time.’ ‘If I got a bad review, he [Danto] would immediately write an incredible review in the New Statesman,’ he says. ‘His two favourite artists were me and Andy Warhol. I always found it bizarre because you couldn’t have two more uncomfortable bedfellows.’

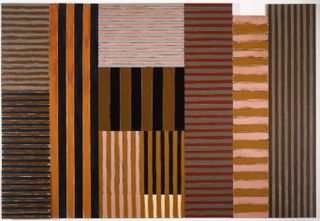

Sean Scully, Backs and Fronts, 1981.

Scully made a swift ascent to acclaim in the 1980s, resuscitating abstraction from self-destruction with bold paintings and a character to match. He began toying with different formats, including the introduction of panels directly inserted into canvases. In came Backs and Fronts (1981), an enormous multi-panelled composite of irregular heights, with gestural stripes careering in different directions like a jarring, psychedelic vision of a city skyline. The painting humanised geometry with hand-rendered stripes and ‘broke a lot of the rules my colleagues were still obeying’. The painting marked a watershed, both for Scully and the public’s perception of his work, paving the way for his formal yet liberated language of unbridled emotion and spirituality.

Earlier this year, Scully’s insets turned uncharacteristically black. In his Dark Windows series, ominous panels rupture otherwise beguiling stripe paintings, described by the artist as ‘nihilistic and negative’. Scully painted these in direct response to Covid-19, a commentary on self-destruction, the ‘abuse of nature’ and mass uncertainty.

Sean Scully, Dark Windows, 2020.

Scully’s approach to art is bolstered by an infectious, and seemingly infallible self-belief. And he doesn’t do creative block, apart from one ‘dreadful’ year after he graduated from university. ‘I made 25 paintings and destroyed them all, and the world is probably a better place for that,’ he says. That episode aside, Scully doesn’t have time for self-deprecation or ‘bellyaching’, a resilience he attributes to his grandmother, an Irish immigrant who, according to Scully, worked 18 hours a day, raised seven children and ‘never once complained.’

Scully’s paintings are rendered with force, exude force and leave the rest to be reckoned with. In footage of the artist at work, he appears to be in some form of rhythmic and spiritual combat with his paintings. ‘In my work, structure and emotion rage simultaneously, and that’s a very incongruous mixture,’ he says. ‘I am madly physical’, he says. ‘People say I’m exhausting.’

In my work, structure and emotion rage simultaneously, and that’s a very incongruous mixture

The artist makes a swift, impassioned pivot to politics, a subject he’s been long engaged in. In his teens, Scully made posters for the CND [Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament]. He has also frequently taken aim at America’s gun culture and, in 2008, he designed billboards for the Obama campaign (one of his paintings boasts wall space in the Obamas’ house). More recently, he’s jumped on the Biden bandwagon, again, in the form of billboards. ‘For Hillary [Clinton], I thought she was going to win so easily I didn’t bother, but she lost. If Joe wins, this will prove that if when I put a billboard up, the person wins. It’s called narcissistic science,’ Scully quips.

Alongside his greatest hits in paint, Scully has demonstrated his aptitude in other media, translating his signature blocks, stripes and volumes into stone, steel, wood and glass. This is embodied in his current exhibition at Waldfrieden Sculpture Park in Wuppertal, Germany, an outdoor exhibition space founded by British artist and ‘old pal’ of Scully’s, Tony Cragg.

Above and below: Installation views of Sean Scully, ‘Insideoutside’ at Waldfrieden Sculpture Park.

Scully’s show, ‘Insideoutside’ includes sculptures in steel, acrylic and copper, and an architectural tower of glass called Stack in conversation with his paintings. ‘The interesting thing about glass is it’s a wall you can see through. In a sense, it’s an object that’s not an object. It operates like a ghost or an angel between realms,’ he reflects. Consisting of eleven slabs of Murano glass, Stack looks as if Scully’s more vibrant painted units have dropped off the canvas, lost all opacity and re-stacked themselves in perfect order.

The artist shows no sign of sitting still. Alongside his Waldfrieden exhibition, he’s just signed with Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, and will have a show of new work in their space in Marais, Paris in Spring 2021. He’s also just unveiled a major retrospective at the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest, his first in Central Europe. ‘I’ve married into that country [Scully's wife, artist Liliane Tomasko is of Hungarian descent], so it has a special significance for them and me,’ he says. Titled ‘Passenger’, the show charts Scully’s career from his early experiments in the 1960s, through his musings with Minimalism to his recent, unexpected shift to figuration, and a great deal in between.

If a Rothko pierces the soul, a Scully will cradle it. His work fuses the cold, hard-edged rigidity of Minimalism with the warm fallibility of humanity, and has, in turn, reformed the very spirit of abstraction. But to what does he attribute his success? ‘I’m kind of clever, and I’m also free. If you put those two things together, you get something.’

Sean Scully, Adoration, 1982.

Sean Scully, ’Passenger – A Retrospective’, 2020, Installation view.

Sean Scully, ’Passenger – A retrospective’, 2020, Installation view.

Sean Scully, Diagonal Inset, 1973.

INFORMATION

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox

'Insideoutside', until 3 January 2021, Skulpturenpark Waldfrieden. skulpturenpark-waldfrieden.de

'Sean Scully: Passenger – A Retrospective', until 31 January 2021, The Museum of Fine Arts – Hungarian National Gallery. en.mng.hu

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.

-

The Emory, RSHP’s first luxury hotel in London, is a rising star

The Emory, RSHP’s first luxury hotel in London, is a rising starNew London hotel The Emory presents the perfect showcase of RSHP’s signature functionalist style and hospitality group Maybourne’s elevated luxury

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

‘Born in Oasi Zegna: The Book’ looks back to the house’s Alpine roots

‘Born in Oasi Zegna: The Book’ looks back to the house’s Alpine rootsPublished by Rizzoli, ‘Born in Oasi Zegna’ looks towards the Oasi Zegna natural territory in the Italian Alps, where ZEGNA opened its first wool mill in 1910 and has since fostered a thriving natural ecosystem of more than 500,000 trees

By Jack Moss Published

-

The New York art exhibitions to see now

The New York art exhibitions to see nowFrom MoMA to the smaller spaces, here are the best New York art exhibitions to catch before they close

By Hannah Silver Published

-

John Cage’s ‘now moments’ inspire Lismore Castle Arts’ group show

John Cage’s ‘now moments’ inspire Lismore Castle Arts’ group showLismore Castle Arts’ ‘Each now, is the time, the space’ takes its title from John Cage, and sees four artists embrace the moment through sculpture and found objects

By Amah-Rose Abrams Published

-

Gerhard Richter unveils new sculpture at Serpentine South

Gerhard Richter unveils new sculpture at Serpentine SouthGerhard Richter revisits themes of pattern and repetition in ‘Strip-Tower’ at London’s Serpentine South

By Hannah Silver Published

-

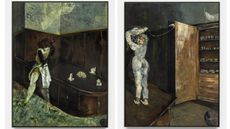

Guglielmo Castelli considers fragility and violence with painting series in Venice

Guglielmo Castelli considers fragility and violence with painting series in VeniceGuglielmo Castelli’s exhibition ‘Improving Songs for Anxious Children’ at Palazzetto Tito, Venice, explores childhood as the genesis of discovery

By Sofia Hallström Published

-

‘Accordion Fields’ at Lisson Gallery unites painters inspired by London

‘Accordion Fields’ at Lisson Gallery unites painters inspired by London‘Accordian Fields’ at Lisson Gallery is a group show looking at painting linked to London

By Amah-Rose Abrams Published

-

Peter Blake’s sculptures spark joy at Waddington Custot in London

Peter Blake’s sculptures spark joy at Waddington Custot in London‘Peter Blake: Sculpture and Other Matters’, at London's Waddington Custot, spans six decades of the artist's career

By Hannah Silver Published

-

Oozing, squidgy, erupting forms come alive at Hayward Gallery

Oozing, squidgy, erupting forms come alive at Hayward Gallery‘When Forms Come Alive: Sixty Years of Restless Sculpture’ at Hayward Gallery, London, is a group show full of twists and turns

By Hannah Silver Published

-

New glass sculpture creates a verdant wonderland at Apple’s Cupertino HQ

New glass sculpture creates a verdant wonderland at Apple’s Cupertino HQ‘Mirage’ at Apple Park is the work of Zeller & Moye and artist Katie Paterson, a shimmering array of glass columns that snakes through the grounds of the company’s monumental HQ

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

Man Ray’s sculptures go on show in New York

Man Ray’s sculptures go on show in New York‘Man Ray: Other Objects’ opens at Luxembourg + Co, New York, revealing their author’s ‘artistic revolution’

By Hannah Silver Published