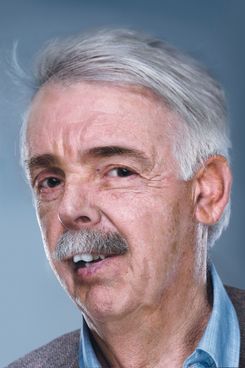

Let’s get a few things straight. First of all, it’s pronounced “Pynch-ON.” Second, the great and bewildering and, yes, very private novelist is not exactly a recluse. In select company, he’s intensely social and charismatic, and, in spite of those famously shaming Bugs Bunny teeth, he was rarely without a girlfriend for the 30 years he spent wandering and couch-surfing before getting married in 1990. Today, he’s a yuppie—self-confessed, if you read his new novel, Bleeding Edge, as a key to the present life of a man whose travels led one critic to reflect: “Salinger hides; Pynchon runs.” Now Pynchon hides in plain sight, on the Upper West Side, with a family and a history of contradictions: a child of the postwar Establishment determined to reject it; a postmodernist master who’s called himself a “classicist”; a workaholic stoner; a polymath who revels in dirty puns; a literary outsider who’s married to a literary agent; a scourge of capitalism who sent his son to private school and lives in a $1.7 million prewar classic six.

Other high-serious contemporaries, like Don DeLillo and Cormac McCarthy, have avoided most publicity out of a conviction that their work should stand apart, and they’ve largely succeeded; no one stakes them out with telephoto lenses, and everyone takes their reticence as proof of their stature. But Pynchon, by truly going the countercultural distance—running farther, fighting harder, and writing wilder—has crafted a more slippery persona. He doesn’t just challenge his fans; he pranks them, dares them to find out what he’s really about (or maybe just to stop exalting Important Writers in the first place). He’s said he wants to “keep scholars busy for several generations,” but Pynchon academics, deprived of any scrap of history, find themselves turned into stalkers.* The more he flees, the more we want—even now that, at 76, he’s just another local writer you wouldn’t recognize on the street. Though likely you have heard the rumors: He was the Unabomber; he was CIA; he wrote ornery letters to the editor at a small-town newspaper in character as a bag lady. In 1976, a writer named John Calvin Batchelor wrote a long essay arguing that Pynchon didn’t exist and J. D. Salinger had written all the novels. Two decades later, Batchelor and Pynchon published stories on the same page of the newsletter of New York’s Cathedral School, which both their children attended. Their bylines were side by side: “John is a novelist”; “Tom is a writer.”

Tom is quite a writer. He’s been credited, justly, with perfecting encyclopedic postmodernism in his third novel, Gravity’s Rainbow, as well as in other kaleidoscopic epics and a few books he’d call potboilers and others would call the minor work of a giant. Bleeding Edge, out in September, is a love-hate letter to the New York City of a dozen years ago, when Internet 1.0 gave way to the fleeting traumas of September 11. It takes place partly on Long Island—where he was raised—but largely on what his detective heroine knows as “The Yupper West Side.” And it’s a book about something he’s never really addressed before: home.

Batchelor and Pynchon probably know each other by now (though neither has answered interview requests). But their first point of contact was a note Pynchon wrote in response to that original article, postmarked from Malibu and written, curiously, on MGM stationery. “Some of it is true,” Pynchon wrote of the story, “but none of the interesting parts. Keep trying.”

Early on in Gravity’s Rainbow, Tyrone Slothrop muses bitterly on his old-money roots. “Shit, money, and the Word, the three American truths, powering the American mobility, claimed the Slothrops, clasped them for good to the country’s fate. But they did not prosper … about all they did was persist.” It sounds like an ungenerous rendering of the Pynchons, one of those Wasp lineages whose historical prominence leaves their ancestors with a burdened inheritance. For a would-be writer with his own stubborn ideas, it was a source of pride and shame.

The name goes back to Pinco de Normandie, who came to England at the side of William the Conqueror, and carries on through Thomas Ruggles Pynchon, the author’s great-great-uncle, president of Trinity College and the first Pynchon to take issue with the family’s portrayal by another writer (Nathaniel Hawthorne, who wrote of the “Pyncheons” in The House of the Seven Gables). Thinkers, surveyors, and religious mavericks, the House of Pynchon had settled into middle-class respectability by the time this Thomas Ruggles Pynchon was born near Oyster Bay, Long Island, in 1937.

His father, Thomas Sr., remembered saluting fellow congregant Teddy Roosevelt at church, and remained a staunch Republican along with most of Long Island’s mid-century Establishment. Eisenhower was their man, and the growing white suburbs of postwar New York their constituency. Thomas Sr. went into engineering like his own father but wound up, for a time, in politics. He was Oyster Bay’s superintendent of highways and then, briefly, town supervisor (the equivalent of mayor), until he was accused of complicity in a scheme to overpay a road-surfacing company. At a hearing during his campaign, Pynchon Sr. admitted to taking gifts. “I received some poinsettias and I managed to keep one alive,” he told his accuser, “and it will give me great pleasure to put one on your political grave.” Instead he lost, giving way to the town’s first Democratic supervisor in 32 years. His son was out of the house by then, but he’d seen enough of small-town, big-boss politics to float “The Republican Party Is a Machine” as an alternate title for his first novel, V. A family friend remembers the Pynchons, in their simple frame house, as “a very bookish family” with a large library to complement the ancestral portraits. On Sundays, the three children would split off between churches—Episcopalian for Dad, Catholic for Mom (a nurse from upstate)—and reassemble later at Rothmann’s Steak House.

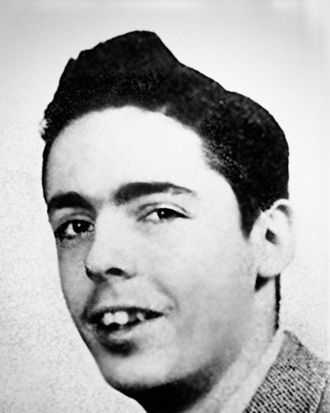

Tom was lanky and unathletic, with protruding teeth that embarrassed him. He stuttered, too, and felt a kinship with Porky Pig. But that same friend ascribes some of Pynchon’s “social behavior issues” to his “very dysfunctional family”—without elaborating. Pynchon himself almost never talked about his parents, especially in his earlier years. But one afternoon in the mid-sixties, he and his then-girlfriend, Mary Ann Tharaldsen, were driving through Big Sur when she complained of nausea. She wanted to stop at a bar and have a shot to settle her stomach. According to Tharaldsen, he exploded, telling her he would not tolerate midday drinking. When she asked why, he told her he’d seen his mother, after drinking, accidentally puncture his father’s eye with a clothespin. It was the only time, says Tharaldsen, who lived with him, that he ever mentioned his family. “He was disconnected from them,” she says. “There seems to have been something not good there.”

A voracious reader and precocious writer, the young Pynchon skipped two grades, probably before high school, and channeled his suburban alienation into clever parodies of authority. He wrote a series of fictional columns under pseudonyms in his high-school paper in which teachers used drugs, shot off guns, and were driven insane by student pranks. In one story, a leftist agitator “got acquainted with the business end of a night stick the hard way.” Pynchon later recalled that his first “honest-to-God” story was about World War II—though in his recollection it doubled as a plan for how to navigate the stultifying culture of postwar America. “Idealism is no good,” he summarized. “Any concrete dedication to an abstract condition results in unpleasant things like wars.”

Engineering physics, the hardest program at Cornell, was meant to supply Cold War America with its elites—the best and the brightest, junior league. One professor called its students “intellectual supermen”; Pynchon’s old friend David Shetzline remembers them as “the slide-rule boys.” But after less than two years in the major, Pynchon left Cornell in order to enlist in another Cold War operation, the Navy. He once wrote that calculus was “the only class I ever failed,” but he’s always used self-deprecation to deflect inquiries, and professors remembered universally good grades. Tharaldsen says she saw Pynchon’s IQ score, somewhere in the 190s. So why would he leave? He wrote much later about feeling in college “a sense of that other world humming out there”—a sense that would surely nag him from one city to another for the rest of his life. He was also in thrall to Thomas Wolfe and Lord Byron. Most likely he wanted to follow their examples, to experience adventure at ground level and not from the command centers.

Although he did come out of the Navy with the tales of bumbling and debauchery that animate V., Pynchon didn’t make much of an impression himself. Stephen Tomaske, a librarian who spent decades tracking his life, found only a couple of old shipmates who’d even known his name. “It’s my sense,” he mused to one of them, “that when you’d stop in Barcelona and the sailors would go to bars and whorehouses, he’d go to see a death cast of Chopin’s hands.” Everything was a curiosity to him, and Pynchon later wrote that his time abroad during the Suez crisis turned him “from a Romantic into kind of a classicist,” which he defined as a writer who thought “other people were more interesting than I was and therefore better to write about.” His Navy-era friends told me that he didn’t plan on going back to school, but he did—this time to study English.

“I thought he was a little weird,” says Pynchon’s Cornell friend Kirkpatrick Sale. “He stayed by himself most of the time.” But the goateed introvert came out for a beer once in a while, and noodled around on a guitar. He and Sale began writing an operetta, called “Minstrel Island,” about a land to which artists escaped from a square America ruled by IBM. “That gray-flannel-suit world was very much our future,” Sale says, “and we wanted of course to avoid it.” The goofy, unfinished musical was a precursor to Pynchon’s grand project—charting the fantasies and fears of individuals fleeing an all-consuming machine (Republican, electronic, whatever). Like Pynchon, these figures generally begin as straight arrows—Slothrop the military Wasp; The Crying of Lot 49’s Oedipa Maas coming home from a Tupperware party—insiders forced out by awful visions they never asked to see.

Pynchon absorbed a lot from Cornell’s powerhouse English department (though there’s no proof that he was taught by Vladimir Nabokov, as many assume). But he learned as much from his peers. He roomed with the writer and singer Richard Fariña, who would become one of his closest friends and, in a sense, his alter ego. Fariña was the man-about-campus, an expert self-mythologizer. Pynchon described their friendship in a rare interview—by fax—for David Hajdu’s cultural biography Positively Fourth Street. “He was the crazy one, I was the rationalist,” he wrote. “He was engagé, I was reserved—he was relaxed, I was stuffy.” Shetzline told Hajdu that he thought Pynchon was “fascinated with Richard’s effect on women, which was powerful.” It was Fariña (and Sale) who participated in a minor riot at Cornell that anticipated the student turmoil of the sixties, hurling eggs and holding signs reading APARTMENT PARTIES ARE MORAL!! EDUCATIONAL!! NECESSARY!! Pynchon—always the observer, seldom the joiner—didn’t attend.

Fariña’s one novel, Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, would transform those years into a Beat romp, the kind of mythopoetic veiled autobiography Pynchon resisted. But he’d blurb his friend’s book as “a joy from beginning to end … like the Hallelujah Chorus done by 200 kazoo players with perfect pitch.” And he saw its value as the document of a generation. It was the bildungsroman of his Cornell circle—a group, raised to inherit the Establishment, who built the hippie generation instead.

After graduating near the top of his class, Pynchon declined a teaching fellowship but immediately applied for a Ford Foundation grant to write opera librettos. Perhaps it’s the sheer hubris of the application, which didn’t even propose a specific project, that led him, decades later, to suppress it—or the fact that it was part of a dream life that didn’t pan out. The 22-year-old’s competition included Robert Lowell and Richard Wilbur. While admitting he’d published only two stories (though boasting he had sold a third and been very well reviewed in the campus paper), Pynchon described his literary development with astonishing self-confidence: “a Tom Wolfe period, a Scott Fitzgerald period, a Byron period … a Henry James period, a Nelson Algren period, a Faulkner period,” and so on. He suggested he could make a libretto out of science-fiction stories, maybe Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles. (Pynchon grew up on the genre.) He had doubts about his lyrical talents, though “I have this guitar on which I occasionally kill time making up rock ‘n’ roll lyrics.” As for where he’d like to work, “Chicago is where my girl goes to school.”

That girl and that fellowship may have presented, for Pynchon, an opportunity for a middle-class life—steady income, a wife, a starter home. Toward the end of school, he’d gotten into a serious relationship with Lilian Laufgraben. They might have married, but her parents disapproved of her dating anyone who wasn’t Jewish. Jules Siegel, in a 1977 Playboy exposé on his ex-friend Tom, got her name wrong (possibly on purpose) as “Ellen Landgraben,” and until now only close friends knew her real name. In 1962, Laufgraben married a psychiatrist. (Today they live not far from Pynchon, but refuse to discuss the connection.) Pynchon gave the breakup as a reason to skip Kirk Sale’s New York wedding to a mutual friend, Faith, who edited early drafts of V. Lilian, he wrote, was getting married to “a nice safe Reformed-temple medical student from her hometown, and this is enough to blight the entire area for me.” A mutual friend, C. Michael Curtis, believes that the nose-job interlude in V., in which Jewish princess Esther is graphically carved up, was Pynchon’s “way of exorcising his angry feeling about losing her.”

Waiting on both Lilian and the Ford Foundation, Pynchon crashed on friends’ foam pads in New York, spending his days writing and his nights sampling the beatnik fantasy, seeing Ornette Coleman and “nursing the two-beer minimum.” (He tried pot once and hated it—for the time being.) He didn’t get the grant, but Lippincott editor Cork Smith accepted Pynchon’s story “Low-Lands” for an anthology and offered to buy his novel-in-progress. Candida Donadio, a fiercely loyal and supportive agent Pynchon had gotten through a professor at Cornell, secured $1,500 for it—$500 up front. Pynchon used the money to skip town.

Two of Pynchon’s Cornell friends, his future girlfriend Tharaldsen and her then-husband, David Seidler, had moved to Seattle and encouraged Pynchon to join them. Tharaldsen says Pynchon arrived “depressed—very down.” She worked for Boeing, and hooked him up with a job writing technical copy for their in-house guide, Bomarc Service News. The aerospace giant was just then developing the Minuteman, a nuclear-capable missile that likely inspired Pynchon, years later, to cast Germany’s World War II–era V-2 rocket as the screaming menace of Gravity’s Rainbow. (One of the joys of tracking Pynchon is tracing the far-flung interconnections in his work to unlikely real-world experiences—dating an NSA worker; seeing Charles de Gaulle in Mexico; fooling around on a primitive music synthesizer in 1972.)

One colleague remembered Pynchon as ornery and solitary on the job. But he managed to turn in V. eighteen months after signing the contract, meeting his own arbitrary deadline on the nose. After a few months of intense editing by mail, he used the $1,000 to quit his job at Boeing, vowing never to work for a corporation again. He called it his “escape money,” and he wanted to make it last—by running again, this time to Mexico.

His alienation had begun to coalesce into a worldview. Pynchon had written to the Sales that Seattle “is a nightmare. If there were no people in it it would be beautiful.” In his next letter, he complained that a group of “ten more or less individuals” at Boeing, “assembled in a conference room … turned into something else: The Magazine.” His letters, like his books, brim with the tension between individuals and groups, between intense curiosity and hopeless disillusionment. For much of his life he would flee crowds and cities, dipping a toe into cultures and communities and then leaving and skewering them in turn. (Friends describe him, in person as on the page, as an incomparable mimic.) Only rarely do we see him ask himself why—as when the Sales, later, pressed him on whether he hated Mexico, too. “What I hate is inside, not outside,” he wrote back, “a kind of deathwish I never knew I had.

In his few public pronouncements, Pynchon has reacted to the term recluse with either defiant denial (“ ‘Recluse’ is a code word generated by journalists … meaning, doesn’t like to talk to reporters,” he told CNN) or self-mockery (“Get your picture taken with a reclusive author!” he yelled to passing traffic on The Simpsons). He did experiment with the condition in Mexico, but he wasn’t cut out for the Salinger school of reclusion; he was too restless for that. A “dedicated sucker” for fictional chase scenes, he seemed to need them in real life, too, whether he was the pursuer or the pursued.

Published in early 1963, V. was a shockingly polymorphous novel for its time, focused on two protagonists: Benny Profane, who bounces around passively like the yo-yo that recurs throughout; and Herbert Stencil, who’s on an epic quest for the elusive, hidden order represented by the title, V.

Pynchon was nominated for a National Book Award, won a Faulkner First Novel prize, and was hounded by the press. In a letter to the Sales, he recounted his escape from two Time/Life reporters in Mexico City with a mix of pain and exhilaration. He happened to be out; his landlady told them “she didn’t know nothing, and go away”; he hid out in a motel over the weekend; later he retrieved his stuff and fled for Guanajuato. He suspected that “Lippinfink” was responsible. “So like please, please,” he concluded, “help me stay under cover.”

What finally smoked him out was Richard Fariña’s wedding to Mimi Baez, sister of the famous folk singer. In August, Pynchon took a bus up the California coast to serve as his friend’s best man. Remembering the visit soon after, Fariña portrayed Pynchon with his head buried in Scientific American before eventually “coming to life with the tacos.” Pynchon later wrote to Mimi that Fariña teased him about his “anti-photograph Thing … what’s the matter, you afraid people are going to stick pins; pour aqua regia? So how could I tell him yeah, yeah right, you got it.”

After Fariña’s wedding, Pynchon went up to Berkeley, where he met up with Tharaldsen and Seidler. For years, Pynchon trackers have wondered about Tharaldsen, listed as married to Pynchon in a 1966–67 alumni directory. The real story is not of a secret marriage but a distressing divorce—hers from Seidler. Pynchon and Tharaldsen quickly fell in love, and when Pynchon went back to Mexico City shortly after John F. Kennedy was assassinated, Tharaldsen soon followed.

In Mexico, Tharaldsen says, Pynchon wrote all night, slept all day, and kept mostly to himself. When he didn’t write, he read—mainly Latin American writers like Jorge Luis Borges, a big influence on his second novel, The Crying of Lot 49. (He also translated Julio Cortázar’s short story “Axolotl.”) His odd writing habits persisted throughout his life; later, when he was in the throes of a chapter, he’d live off junk food (and sometimes pot). He’d cover the windows with black sheets, never answer the door, and avoid anything that smelled of obligation. He often worked on multiple books at once—three or four in the mid-sixties—and a friend remembers him bringing up the subject of 1997’s Mason & Dixon in 1970.

Tharaldsen grew bored of the routine. Soon they moved to Houston, then to Manhattan Beach. Tharaldsen, a painter, did a portrait of Pynchon with a pig on his shoulder, referencing a pig figurine he’d always carry in his pocket, talking to it on the street or at the movies. (He still identified closely with the animals, collecting swine paraphernalia and even signing a note to friends with a drawing of a pig.) Once Tharaldsen painted a man with massive teeth devouring a burger, which she titled Bottomless, Unfillable Nothingness. Pynchon thought it was him, and hated it. Tharaldsen insists it wasn’t, but their friend Mary Beal isn’t so sure. “I know she regarded him as devouring people. I think in the sense that he—well, I shouldn’t say this, because all writers do it. Writers use people.”

Tharaldsen hated L.A., and decided to go back to school in Berkeley. “I thought they were unserious sort of beach people—lazy bums! But Tom didn’t care because he was inside all day and writing all night.” At the moment, eager to break with his publisher, Lippincott (and rejoin Cork Smith, since departed to Viking), he saw Lot 49 as a quickie “potboiler” meant to break his option with the house—forcing them to either reject it, liberating him, or pay him $10,000. They paid him, defying his own low opinion of it. In his introduction to Slow Learner, a later collection of his early stories, he’d write that with Lot 49, “I seem to have forgotten most of what I thought I’d learned up till then.” Now it’s required reading in college courses, a gateway drug to the serious stuff. Which, of course, was his next book: Gravity’s Rainbow.

On the day Fariña’s Been Down So Long was published, the debut author went for a ride on the back of a motorcycle, crashed, and was killed. Pynchon, devastated, wrote to Mimi that Fariña had made him “more open to myself, to experience.” But in the wake of his friend’s death, he seemed only more determined to live purely for himself. By one account, he tried pot more seriously in Berkeley around 1965; it seems this time it took. Later in life, he was known to keep a simple sign up above his desk: ESCHEW SLOTH. Gravity’s Rainbow is evidence of his success, but in Manhattan Beach, sloth was never further than the surf two blocks from his one-bedroom apartment, or the next delivery of Panama Red, a potent brand of weed smuggled in by a paratrooper with PTSD.

The poet Bill Pearlman, who knew him in those days, once wrote that he “got the impression Pynchon wanted no part of the middle-class adult world”—that he “got more pleasure and information from the young, and was in some ways childlike himself.” There grew around Pynchon, by the beach, something that looks from the distance of years like a cult—a cult of privacy, at least, which paradoxically helped cement the legend of Tom the Recluse. “He was surrounded by a group of people that protected him fiercely,” says Jim Hall, a peripheral member, “and you either were accepted on some level or you were not.”

With his straggly hair and mustache and Army-surplus clothes, the writer who’d once resembled William Faulkner now looked more like Frank Zappa. For a while he took in a girlfriend, the young daughter of Phyllis Coates, TV’s original Lois Lane, and looked after her son, Ethan. “They huddled up in that little dump he lived in,” Coates remembers. “Tom was very good to Ethan.” There was lots of what was once called getting together and is now called hooking up. Among the women was Chrissie Jolly, the wife of Jules Siegel, which is why his Playboy exposé was titled “Who Is Thomas Pynchon … and Why Did He Take Off With My Wife?”

Siegel and Jolly wrote a short book about Pynchon, in which Jolly said he “could slip into any character he wanted. He was really crafty, methodical.” For good measure, she added, “He broke up more than one marriage, because he was too shy to find someone on his own.” Harsh as that may sound, Tharaldsen seconds it: “That seems to be his modus operandi,” she says. “He was very withdrawn, and the one way he could make connections with women would be through his friends … It’s a pattern.”

Gravity’s Rainbow, which begins with a missile screaming across the sky, ends not with a bang but with a dispersal, as the fugitive Slothrop disintegrates into fragments of character and plot. Pynchon, too, seemed to disperse in the wake of the novel, crisscrossing the country like one of his yo-yo protagonists. His work dwelled on individuals on the run from a totalizing government-industrial complex; now, impossible to locate for months at a time, he came to embody his own literary project. Pity, then, that his decade in the wilderness seemed to sap his productivity.

Cork Smith, reunited with Pynchon for Rainbow, cut only 100 out of 1,300 manuscript pages, but didn’t grasp it well enough to attempt any more. It was hailed anyway as a masterpiece—albeit the kind that’s much easier to buy than to finish. As if to burnish his outsider status, the Pulitzer jury chose it for the 1974 fiction prize but the larger committee rejected it as obscene. It did win a National Book Award, which was given by Ralph Ellison to someone he thought might be Pynchon but who turned out to be absurdist comic Irwin Corey, sent by Viking with Pynchon’s approval, thanking the crowd with a string of malapropisms.

Pynchon might have been in the city at the time. From Manhattan Beach he’d followed friends up to pot-saturated Eureka, then crashed in New York. In a letter that winter to the Shetzlines, he vented his disenchantment with a city whose bohemian heyday was over. At the Village Gate, there was to be an “Impeachment Rally” against Nixon. “Why didn’t they have one in ’68?” he asked. He railed against the “third rate heads” of New York, the “dirty, desolate heart” of a declining empire, and the righteous proto-yuppie liberals better known as the “urban assholery.” He couldn’t “dig to live a ‘literary’ life no more.” He and a girlfriend might move “across the sea,” or maybe head back West. “Yes, it does sound like ‘aimless drifting,’ doesn’t it?”

In context, Pynchon’s cri de coeur wasn’t that of a radical but of an artist straddling a deep fissure in American life. His sixties friends had retreated into the California woods, the subject-to-be of a novel, Vineland, that he wouldn’t get it together to finish for seventeen years. His literary peers were assimilated into the “assholery” he disdained. A key word in Gravity’s Rainbow is preterite, which literally means bygone, but in Pynchon takes on the meaning of outside, oppressed, non-elite. And who was he?

“I think he withdrew and went to ground,” says Shetzline. “Had a kind of sit-down about where he stood with American cultural confusion. The middle was hard ground to hold … There was no going home.” Pynchon spoke of “riding the ’Hound”: taking a bus from town to town and always sitting in the back, watching the world with a thermos of coffee growing cold in his hand.

Occasionally he came out to visit the Shetzlines in rural Oregon. “I remember Pynchon on the horse I had,” Shetzline says. “He looked like Don Quixote.” Shetzline’s ex-wife Mary Beal says he mostly stayed up late and watched TV. (Kirk Sale remembers his houseguest arguing with his kids over which cartoons to watch.) After crashing in their daughter’s room, Pynchon gave Beal an odd compliment: “People put me up in their kids’ rooms all the time, and hers is the first bed that doesn’t smell of urine.” The Shetzlines were part of an underground railroad for an author on the run. “He was just Mr. Mysterious,” she says.

Once, at a party out in the woods, a man they knew “outed Tom as a famous writer,” Beal recalls. “And of course nobody in the area reads literary novels—just a bunch of country folk … It mortified Tom to the point where he left the following day.” What could have been so mortifying? Beal thinks it had more to do with being unknown to a room full of people than it did with the one guy who was hounding him.

A Pynchon tracker has found at least one actual “hidey-hole” of his, as Shetzline calls it. Between 1976 and 1977, he spent more than a year in a neat but tiny redwood cabin in Trinidad, California, separated by 300 feet of trees from the lush, rocky shore of the Pacific. It’s deep in Humboldt County, the hippie paradise at the center of Vineland.

But that book wasn’t one of the two he was contracted by Viking to write. Those were Mason & Dixon, about the surveyors, and a never-written novel about an insurance adjuster flown in to Japan to assess the damage done by Godzilla. Viking had granted him a $1 million advance, beginning with $50,000 a year for three years. In his first experiment with reclusion, Pynchon had made do on $1,000 in Mexico; now he was living on a doctor’s salary in a glorified lean-to, years out from a finished book. Having eluded the media and the narcs but not his own paranoia, Pynchon had succeeded in eschewing the machine; now what about sloth?

It took the love of Pynchon’s life to flush him out of the wilderness and back to writing, family, and New York. Melanie Jackson was a sharp and ambitious young literary agent (“the prettiest girl in publishing,” remembers an editor) when she came to work for Candida Donadio. She was also a great-granddaughter of Teddy Roosevelt (Tom Sr.’s fellow churchgoer) and a granddaughter of a Supreme Court justice—a pedigreed Protestant from a town that neighbors Oyster Bay.

Like all good agents, Donadio had been the enabler of Pynchon’s life, the most important station on his underground railroad. Donadio told others Pynchon had been staying in Donadio’s apartment (platonically) when he began dating Jackson. A dispute between Jackson and Donadio resulted in Jackson’s leaving the agency in late 1981. Her first solo client was her boyfriend, Thomas Pynchon.

Together, the couple decided it was time to put out a collection of Pynchon’s early stories—something Cork Smith had brought up earlier to no avail. Smith offered $25,000, but the stories went to Little, Brown for $150,000, according to Smith, and Pynchon wrote an introduction that dismissed four of the five stories as “apprentice efforts.” On a basic level, it was another “option-breaker,” intended to preempt pirated stories and to give Jackson her first sale. (They took the other books away from Viking, too.) But it was also a reckoning with his earlier self, before the hiding and the running, the drugs and the block. He wrote of conflicting reactions brought on by looking back—to recoil or to rewrite—but “these two impulses have given way to one of those episodes of

middle-aged tranquillity, in which I now pretend to have reached a level of clarity about the young writer I was back then.”

Pynchon eased himself gradually, like a scuba diver, back to the surface of mainstream life. He spent a couple more years researching in California, but by the summer of 1988, when he won a $310,000 MacArthur “Genius” grant, he was reached through Jackson in New York (though the MacArthur Foundation had him listed as living in Boston at the time). Vineland came out two years later. A surprisingly accessible, loose, and goofy work about the last refuge of the left in the age of Reagan, it disappointed readers weaned on Pynchon’s dazzling complexity. David Foster Wallace was among the disenchanted. He wrote to Jonathan Franzen that Vineland was “heartbreakingly inferior” and that “I get the strong sense he’s spent twenty years smoking pot and watching TV.” He wasn’t terribly far off, but he missed something, too. His fallen hero had already transformed again, and thrown in his lot—if not exactly with the Reaganites, then certainly not with the shaggy pot-growers of Humboldt County.

Pynchon and Jackson married in 1990 and had a son—first name Jackson—a year later. Pynchon told friends he was seeing a lot more of his parents. His next novel, Mason & Dixon, had far more heft and wild invention than Vineland but sped along more briskly and powerfully than Gravity’s Rainbow. Embedded in it, too, was a far more sophisticated treatment of his American roots—the Pynchons were a long line of surveyors—than his portrait of the decrepit Slothrops. After that came Against the Day, a big and messy novelistic attack on capitalism, written by an author increasingly at peace with its comforts.

The onetime inhabitant of fleabag motels rented an apartment with his family on a major intersection of the Yupper West Side and went cautiously semi-public. Pynchon had already begun writing for the New York Times: an essay in defense of Luddites; a review of Love in the Time of Cholera; a piece on his favorite deadly sin, sloth. Whereas in the past he’d mostly communicated with peers by letter or phone—calling Harlan Ellison “from time to time,” once to badger him to stop paying income taxes, but never giving the author his number—he now sat down for actual meals with Don DeLillo, Salman Rushdie, and Ian McEwan. When the struggling sitcom The John Larroquette Show floated a Pynchon story line, he agreed, so long as it didn’t portray his face and clad his fictional avatar in a Roky Erickson T-shirt. A decade later, he consented to appear on The Simpsons—mainly, he said, because his son was a fan. Showrunner Al Jean remembers a casual, mustachioed figure, son and wife in tow. They discussed private schools and kitchen renovations. Pynchon politely declined a photo-op: “I don’t usually take pictures.” He appeared twice during the show’s run, wearing a paper bag. The first time he didn’t alter a word, but for his second cameo he threw in a bonus pun: “The Frying of Latke 49.”

There’s an apparent randomness to his public excursions, but mostly they hinge on ordinary personal connections. Take his decision to write liner notes for—and then do an Esquire interview with—a pretty good indie-rock band called Lotion. Around the time his father died, in 1995, Pynchon went on an alumni tour of his old high school. He and Rob Youngberg, Lotion’s drummer, happened to be visiting the same music teacher. Dr. Luckenbill had taught them 25 years apart. Then Pynchon ran into Youngberg’s mother in an Oyster Bay bank, and she pressed Lotion’s new album on him. Pynchon dug it, and soon he was in their recording studio, taking notes and rattling off obscure facts about ribbon microphones.

“I just remember being amazed at how fluidly funny he was,” says Youngberg. His bandmate Bill Ferguson was copy chief at Esquire; the magazine pitched an interview, and, to everyone’s surprise, he agreed. The Q&A ran beneath text so strange Pynchon must have written it: “The reclusive novelist loves rock and roll, and its name is, well, Lotion. He wanted to play ukulele, so the band gave him an interview.” Ferguson was impressed by Pynchon’s knowledge, humor, and intensity—but also the skittish, mercurial quality of the interaction: “He’s somebody who just—you see him and he sees you. The thing I have in my head is Robert De Niro in Brazil. He knows the truth but he’s got to get out of here now: ‘Keep doing what you’re doing, I won’t be here long.’ ”

He wasn’t, but he’s stayed put in the city now for a quarter-century. The problem, for someone so deeply private, is that sooner or later the press catches up, as do letters made public by former friends—like Donadio and the Sales. On two occasions—the release of Donadio’s letters to the Morgan Library and the discovery of the Ford Foundation application—Pynchon’s lawyer and agent-wife reacted quickly to have them sealed. Pynchon has always fought publicity, but we look differently upon secrets held by the powerful, and Pynchon has grown powerful. Now that he benefits from mainstream fame, his self-protection feels less political, more psychological.

“He writes what we’d call the imperial way,” says Kirk Sale, with whom Pynchon broke off contact after Sale talked to a reporter. “He creates a world and he has it operate as he wants it to operate. If it doesn’t, he doesn’t like it … So in that sense you can say that he wanted control over his own life as well as his own fiction.”

The last thing we should get straight about Thomas Pynchon is that, “classicism” aside, all of his books are in some way autobiographical. Inherent Vice, for instance, starring a perma-stoned “gum-sandal” detective, owed a lot to the characters Pynchon knew in Manhattan Beach. Maybe it speaks to his special fondness for the book—or just the bucket-list dreams of a movie-mad author—that it’s soon to become his first novel adapted for the screen. It’s currently being directed in L.A. by the “imperial” auteur Paul Thomas Anderson, with Joaquin Phoenix in the lead.

But no book is closer to home than Bleeding Edge. It’s impossible not to read into it a grizzled wanderer’s wary truce with New York, conformity, and life in public. It’s there in the teasing epigraph, a quote from crime writer Donald Westlake that describes the city as “the enigmatic suspect who knows the real story but isn’t going to tell it.” There’s a chase scene across the very same intersection where, in 1998, a South African reporter pursued the author, took an awful photo, and tried to shake his hand. (“Get your fucking hand away from me,” Pynchon said.) There’s also a lyrical flashback in which our heroine spies on a building across the street that’s obviously the Apthorp. His son grew up looking out on that same landmark—from that same window. These feel like mildly dangerous games for a “reclusive author” to play—though the family did move out of that apartment four years ago. (They’ve also bought a summer home—on Long Island, an hour from Oyster Bay.) Bleeding Edge begins and ends with Maxine, an accounting-fraud investigator, tending to her precocious son, Ziggy. They repeatedly mock Collegiate, the high school where Jackson Pynchon went.

It’s a fun-filled, pun-filled thriller, close in spirit to Inherent Vice and surprisingly blasé about its own conspiracy theories. Maxine jokes that “paranoia’s the garlic in life’s kitchen, right, you can never have too much.” September 11, the putative turning point, is treated with the distance and numbness a local feels today—as a catastrophe quickly drowned out by the noise of pop culture and unjust wars and the city’s endless appetite for construction.

The novel’s Pynchon stand-in is Maxine’s on-again-off-again husband, Horst, who confesses at Ikea that his “ideal living space is a not too ratty motel room in the deep Midwest, somewhere up in the badlands.” A wanderer come home to roost, he spends much of the novel watching biopics on Chi Chi Rodriguez and Fatty Arbuckle. The real Pynchon still gets out a lot; one acquaintance sees him on the avenue with almost alarming frequency. But he clearly spends some time indoors. A partial list of the novel’s pop-culture references: Ace Ventura, Ally McBeal, Battlestar Galactica, Beanie Babies, Britney Spears, Furbies, Geraldo, Hypnotiq, Jamiroquai, “More cowbell,” Pokémon (a West Indian proctologist, get it?), the “Rachel” haircut, Warren G., “Whoop There It Is,” Wolfenstein, Zima.

Beneath the mockery, the light skewering of just another community, is an undertow of longing—especially poignant in lyrical descriptions of two places. One is a tiny isle off Staten Island, and the other is virtual—a noncommercial patch of the Internet, still anarchic in 2001. Pynchon compares the two: “Like the Island of Meadows, DeepArcher also has developers after it. Whatever migratory visitors are still down there trusting in its inviolability will some morning all too soon be rudely surprised by the whispering descent of corporate Web crawlers itching to index and corrupt another patch of sanctuary for their own far-from-selfless ends.”

The “departure”/DeepArcher pun is explicit. The pleasure of a Pynchon novel, now as ever, is the conflict its author has always felt between wanting to swallow the world and holding it at bay, celebrating and mocking it, devouring it and protecting himself, and now his family, from being devoured. The novel ends on that note, with a plea for the protection of innocent children from “the indexed world.” These untrammeled spaces really aren’t so different from Minstrel Island, that retreat from IBM he sang about at Cornell in 1958. He still hasn’t found it, at least not outside fiction.

*This article has been corrected to show that Pynchon has said he wants to “keep scholars busy for several generations,” not “keep scholars busy for generations.”