There are three of us around a long wooden table: Gioacchino Lanza Tomasi, the 85-year-old duke, who also happens to be a world-renowned musicologist and opera specialist; Nicoletta, the duchess, who also happens to be an acclaimed chef; and me, the reporter, who, like countless others, also happens to be an obsessive reader of The Leopard, the novel written in the 1950s by the duke’s distant cousin and adoptive father, the late Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa.

In a sense there are four of us here at lunch in the crumbling grandeur of the Palazzo Lanza Tomasi, which overlooks Palermo harbor, dining on Nicoletta’s swordfish with capers and basil fusilli with ricotta salata: Lampedusa is with us too. In the ruins of a world that no longer exists, it is his novel—and his life—we have gathered to discuss.

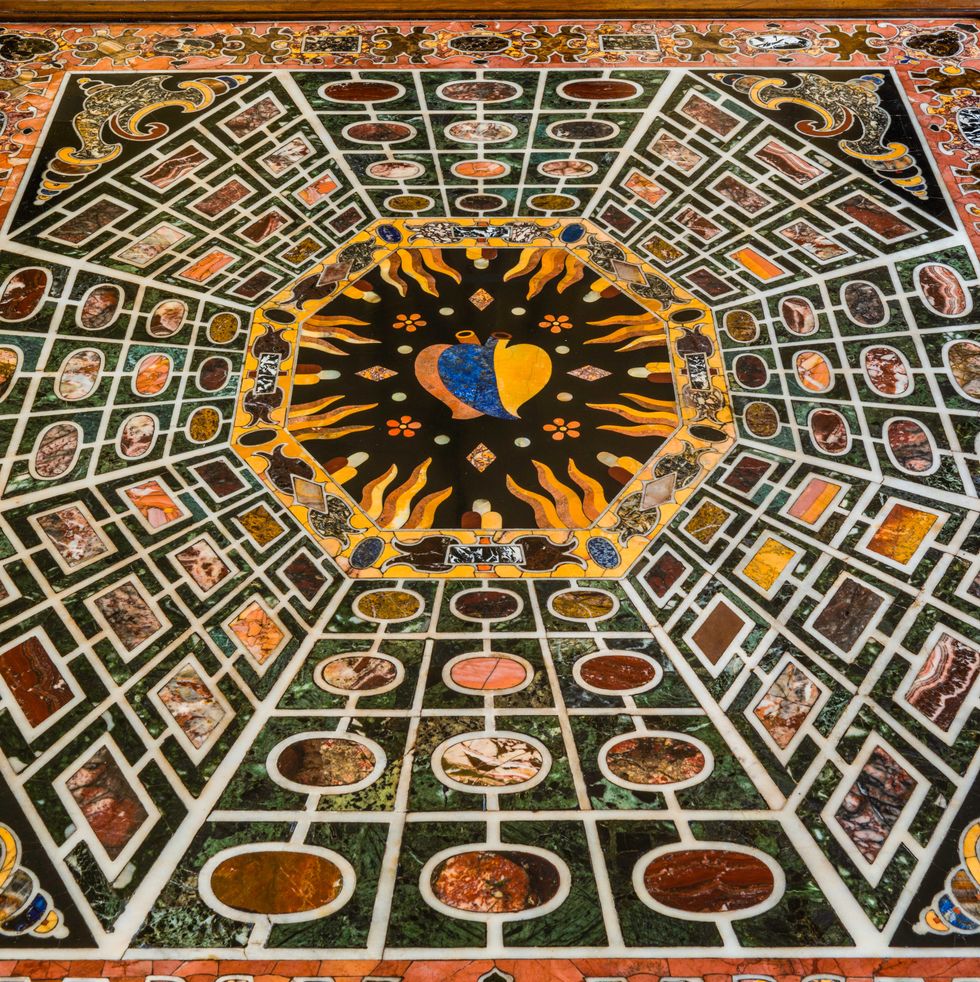

The dining room faces out onto a terrace where unruly flora languish under an unrelenting summer sun. The afternoon light feels as heavy as olive oil as it streams into the grand rococo salons of the house, filled as they are with Murano chandeliers, frescoed walls, and dusty sofas the fading, perfectly primped cushions of which have clearly not seen a derriere in decades.

There is something unsettling about the Palazzo Lanza Tomasi: The house is both the home of a living, very contemporary couple and a monument to an impoverished aristocrat who died in 1957 having written a nearly perfect novel that defined a generation, although he never lived to see its publication.

The Leopard is a book for writers, a flawlessly executed social chronicle in prose as lavish as it is spare. Over the years it has drawn the admiration of authors as diverse as Louis Aragon, Edward Said, and Julian Barnes. “It’s my life,” Gioacchino says, referring to the text, a lyrical, 300-page marvel that is at once the story of the collapse of the Sicilian aristocracy in the 1860s and a haunting meditation on the passage of time.

The two men were related only distantly, but they became close toward the end of Lampedusa’s life. The novelist, who had no children of his own, adopted the young Gioacchino as his son. What’s more, Lampedusa immortalized him as a character in The Leopard: Tancredi Falconeri, the dashing young nephew of the inimitable Prince of Salina, the protagonist.

Gioacchino moved into the palazzo in the 1970s and began the slow process of bringing it back from complete disrepair. “Palaces don’t belong to the individual man,” he says. “They belong to the family.” Once we’ve finished our meal, he beckons for me to follow him up the villa’s marble stairs to the rooms where Lampedusa spent the last years of his life at work on his novel.

First we step into a stately room containing Lampedusa’s collection of books and a writing desk. Then Gioacchino summons me to the ballroom and a series of vitrines, inside of which are Lampedusa’s diaries, his pocketbooks, and the covers of the many international editions of The Leopard.

Most precious, Gioacchino says, are the pages of Lampedusa’s original manuscripts, which are covered in his adopted father’s loopy marginalia.

Sudden Acclaim

When it came out in 1958, The Leopard seemed an unlikely candidate to become a cult classic. Marxism remained an influence in much of postwar Europe’s social thinking, and few readers, it was believed, would be interested in the travails of the wealthy. But after his death, Lampedusa’s manuscript was championed by the novelist Giorgio Bassani, author of In the Garden of the Finzi-Continis, who shepherded it through publication and to immediate and international success. Five years later The Leopard was reimagined as a lavish film by Luchino Visconti; Martin Scorsese has called it one of the greatest movies ever made.

In one of the most memorable scenes in the film, members of the Salina family (Lampedusa’s fictional rendering of his noble clan) assemble with their guests for an elaborate ball in the family mansion, a place Visconti recreates in a way that captures perfectly the “sumptuously second-rate” space of Lampedusa’s description.

Burt Lancaster, who plays Prince Salina, waltzes with the beautiful young Angelica, played by Claudia Cardinale, to the sound of Shostakovich’s Second Waltz, and then the narrator delivers a line from the novel: “From the ceiling the gods, reclining on gilded couches, gazed down, smiling and inexorable as a summer sky. They thought themselves eternal, but a bomb manufactured in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was to prove the contrary in 1943.”

This was Lampedusa’s reference to the destruction of his own family estate during the Second World War—and the beginning of the author’s own final act.

The Last Prince

Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa was an obscure, minor European aristocrat born in 1896 to a family whose names united duchies and principalities across a sprawling map. His father was Giulio Maria Tomasi, Prince of Lampedusa, a minuscule Mediterranean island between Sicily and Tunisia, but his other titles included Duke of Palma di Montechiaro, Baron of Torretta, and even Grandee of Spain.

His mother was Beatrice Mastrogiovanni Tasca Filangeri di Cutò, the heir to a family with deep roots in Naples. In 1932, Giuseppe married Alexandra von Wolff-Stomersee, a psychoanalyst whose mother was the famous Italian mezzo-soprano Alice Barbi and whose father was a Latvian nobleman, Boris von Wolff-Stomersee.

The couple traveled in cosmopolitan circles for whose members nationalities were mere formalities. They lived, as the Lampedusas did, in various European capitals and paid little mind to which country they were residing in at any given moment. Like many of his class, Lampedusa did not participate in politics, believing himself exempt from the affairs of state that controlled the lives of others. But history finally came for people who believed they had somehow transcended it, or fooled it, and Lampedusa was no exception.

During World War I he was drafted into the Italian army and in 1917 fought in the Battle of Caporetto—in present day Slovenia—against the Austro-Hungarians; he was captured and sent to a POW camp. He eventually escaped and returned to an Italy transformed, its economy in ruins, its social fabric in tatters—a country where a young army officer named Benito Mussolini was quickly rising in the ranks of government.

The 1920s and ’30s were punctuated by frequent, violent political clashes. According to David Gilmour, Lampedusa’s biographer, the writer was neither a fascist nor an avowed anti-fascist, and he was “too skeptical and disillusioned to be a genuine democrat or a liberal.” One of the most surprising things about Lampedusa is that he lived through such times but had little substantive to say about them (publicly, at least). For him, stoic silence may have been the only way to survive.

In 1940 he was drafted once again—this time into Mussolini’s army—but he was soon permitted to return home to tend to his failing estate. In 1943 the sprawling palazzo in Palermo that had been the family seat for generations and would serve as inspiration for the novel was destroyed by American artillery. The Lampedusas, their fortunes diminished, eventually moved into another family palazzo (the one in which Gioacchino and Nicoletta Lanza Tomasi now reside), and Giuseppe began work on his manuscript.

Inspiration Point

In addition to novelists and filmmakers, the book and movie of The Leopard have served as touchstones for a broad array of aesthetes. The shoe designer Manolo Blahnik rereads the novel every year and watches the film over and over again for inspiration. The interior designer Michael S. Smith refers to the movie in his book Elements of Style and says he used it as inspiration for a California home he designed. It’s easy to see why. There’s something intoxicating about Lampedusa’s wry prince and his decaying palaces.

Gioacchino is quick to point out, however, that the novel doesn’t really romanticize the nobility of its characters or lament the evaporation of their world. Instead it chronicles a moment in time that eludes both the comprehension and the control of the people who inhabit it.

Before he settled on the title The Leopard, Lampedusa referred to his work as “histoire sans nom,” or “history without a name,” which Gioacchino says captures one of the book’s recurring themes: the unstoppable progression from order to disorder and from potency to decay. “Wealth, like an old wine, had let the dregs of greed, even of care and prudence, fall to the bottom of the barrel, leaving only verve and color,” Lampedusa writes in the novel. “And thus eventually it canceled itself out; this wealth which had achieved its object was composed now only of essential oils—and, like essential oils, it soon evaporated.”

In late May 1957, three months before he died—and more than a year before The Leopard would be published—Lampedusa wrote a letter to his lifelong friend Enrico Merlo, a Sicilian man of letters whom he met nearly every day at Palermo’s Caffè Caflisch. Lampedusa’s manuscript had been rejected by almost all of Italy’s most prestigious publishing houses. Lampedusa sought to explain to his friend the essence of the project he had been laboring over. “It evokes a Sicilian nobleman at a moment of crisis…how he reacts to it and how the degeneration of the family becomes ever more marked until it reaches almost total collapse,” he wrote. “All this, however, seen from within, with a certain connivance of the author and with no rancor.”

As it happens, “with no rancor” was the way Lampedusa lived. His response to tumultuous times was to maintain an attitude of nonchalance, an unflappable sense of irony, and a certain resignation to things beyond his control, as indeed so many things had proved to be. “He ended his life living on the equivalent of 50 euros a day,” Gioacchino says. “And yet he was completely without regret.”

The Inheritance

Gioacchino takes me on a tour of the rest of the house. We walk past a second staircase adorned with sculptures, and through a living room with a view of bougainvilleas and, beyond, the sapphire sea. Along the way he reflects on The Leopard ’s lessons and wonders whether they apply now. Today is not the 1930s, but in contemporary Italy, for instance, a populist government has taken power and started openly targeting migrants with a vehemence few thought possible in postwar Europe. There has been a return of anti-Semitism and, in general, a disquieting embrace of xenophobia across the continents.

For Gioacchino, all of this is difficult to ignore; he says there is something that counts even more than Lampedusa’s surging waves of history and acknowledging our ultimate powerlessness before them. “Trauma is more important than history,” he says. “Trauma is what we live in.”

Gioacchino’s favorite section of the novel is near the end, the description of the death of the prince. Plotwise, not much happens. There is no dramatic intervention before the prince succumbs to a second stroke, and there is no final profound realization, just a quickening stream of his thoughts.

He weighs the pleasures of his life against the burdens, and it turns out they hardly compare: “He was making up a general balance sheet of his whole life, trying to sort out of the immense ash heap of liabilities the golden flecks of happy moments.” And then it comes to a deafening halt.

Like many of Sicily’s old families, these days Gioacchino and Nicoletta rent out parts of their estate to vacationers. Nicoletta runs a cooking school out of the villa’s kitchen, where she welcomes students from around the world for intensive workshops in Sicilian pasta-making. “Live like a local, and a royal one at that, but with the safety net of a concierge,” reads a recent Michelin review of the estate.

Gioacchino discusses these arrangements with detached amusement, and as he does so it becomes clear that he, Lampedusa, and the Prince of Salina are all versions of the same character—an anachronism adrift in a universe he never expected to see. “We had this affinity. We were quite similar,” Gioacchino says of Lampedusa, as he sips his coffee on the terrace. The salty breeze of the sea rustles the leaves of the canopy as he speaks. “Our relationship to palaces, to places like this—we had the same world, and now I’m one of the only survivors.”

Deluxe apartments from $225 per night (two night minimum) butera28.it

This story appears in the December 2019/January 2020 issue of Town & Country.

SUBSCRIBE NOW