Bankrobber and serial prison escapee Jacques Mesrine had many names during his two-decade criminal career in the 1960s and 70s.

In disguise and on the run from police, he made headlines as “the man of a thousand faces” and “public enemy number one”. In Canada and the US with his girlfriend, Jeanne Schneider, the couple were nicknamed France’s Bonnie and Clyde.

Now hundreds of letters Mesrine wrote to Schneider during more than 10 years in prison are to be auctioned in Paris. Like the notorious Al Capone, Ronnie Biggs and Jesse James, Mesrine has entered popular culture as the 21st century’s ideal antihero, despite a record that included armed robberies and hold-ups, swindles, kidnappings, abductions and – allegedly – murders.

Said to be charismatic and intelligent, roguish and romantic, he had a good line in pithy maxims that played to his image as a French Robin Hood.

“I’ve no remorse about stealing from banks. I’ve the impression of stealing from someone more of a thief than I am,” he wrote in his book L’instinct de mort (Death Instinct) published in 1977.

At one of several court appearances in the 1970s, he said: “I am not a public enemy. I am the enemy of the banks. I eat the cake, not the grandmother nor Little Red Riding Hood.”

At the same time, the man who said “I became a crook as one becomes a doctor, by vocation”, would mock those who would depict him as a good guy for the poor and downtrodden. “The terrible thing is that some people are going to make a hero out of me, but there are no heroes in crime. There are only men who are marginal and who don’t accept the law.”

Pauline Ribeyre, of auctioneers Baron Ribeyre, selling the letters on behalf of Schneider’s daughter, Murielle, said they were of historic interest. “Mesrine remains a major criminal and it’s not our intention to glorify him or do any publicity for him. The family [Schneider] do not defend what he or their mother did,” Ribeyre told the Observer.

“This private correspondence shows another face of the man Mesrine. We see he could be quite funny, romantic, a bit misogynistic, but very much in love.”

She added: “The question is what you do with all the letters like this? Mesrine was what he was – a serious criminal – but do you just throw them away or do you see them as a vital historic souvenir?”

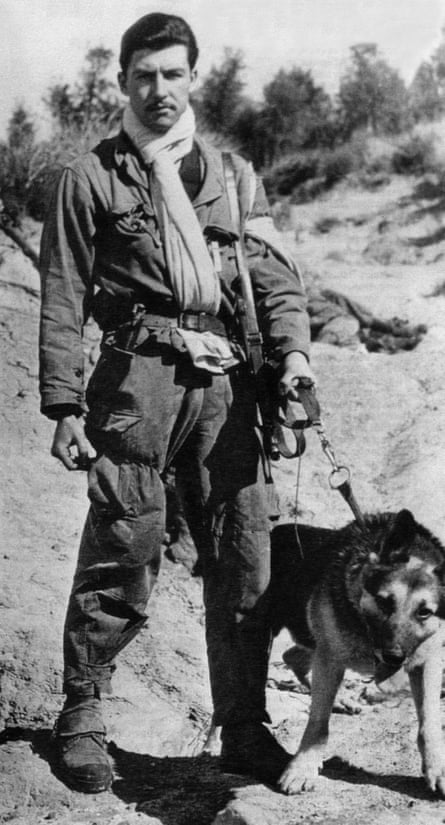

Jacques René Mesrine was born in Clichy, near Paris, in 1936 into a well-off Catholic family. His parents ran a luxury clothing outlet and hoped he would join the business, but the young Mesrine was not interested in school or becoming a salesman. His criminal career began at the age of 23 after his return from decorated military service in Algeria. It ended 19 years later in a hail of police bullets on a street in the north of Paris.

He and Schneider, nicknamed Janou, met in a Paris bar in about 1965. Two years later, while Mesrine was being hunted by police for mostly petty swindles in the Canary Islands, Switzerland and France, the couple fled to Canada. There they continued a joint life of crime, including holding a disabled millionaire hostage and demanding a ransom from his family.

Later jailed, Mesrine escaped and travelled to Venezuela. Schneider was extradited to France where she served out the rest of her sentence and began a crime-free life on her release. She died aged 66 in 2006.

In 1973, after returning to France where he was arrested, Mesrine staged a spectacular escape from a courthouse by taking the judge hearing his case hostage.

When his nemesis, the police commander Robert Broussard, now 87, came to arrest him at his flat, Mesrine received him, cigar in mouth, holding a bottle of champagne and offered him a glass. The 400 letters in the sale were written to Schneider between 1972 and 1977, mostly from Mesrine’s time in the high-security wing at La Santé prison in Paris. He was a prolific, if uninspiring, letter writer whose aim seemed to be to continue charming the women under his spell with declarations of enduring love.

after newsletter promotion

In one letter to be auctioned, he recalls visiting Cape Kennedy with Schneider for the launch of Apollo 11 before moving to proclaim: “You are my right shoe and I’m your left shoe…two are needed to run fast”, signing the letter “Good night, my sweet”.

In another, Mesrine describes France as “Chicago” : “The cops shoot three hoodlums and that evening the hoodlums shoot two cashiers…” adding that he is for the death penalty. “I am for and I’ve always been…you are against,” he writes.

In 1977 he escaped once again and abducted a billionaire and a journalist, crimes that sparked the creation of a massive manhunt and an “anti-Mesrine” police squad. Mesrine, who claimed to have killed 39 people – though criminologists suspect this was bravado – was shot dead at the wheel of his BMW in November 1979.

In 2008 a two-part feature film was made of his dubious career with Vincent Cassel in the title role and Gérard Depardieu in the cast. Schneider was played by Cécile de France.

Guardian film reviewer Peter Bradshaw described director Jean-François Richet’s telling of Mesrine’s brutal story as “a fascinating premonition of our modern age of gangsters, gangstas and ‘respect’ ”.

More than 40 years since his death he continues to fascinate, as a Facebook page in his name shows.

“We don’t know who will buy these letters,” said auctioneer Ribeyre. “There aren’t many people from his era who might have known him still alive, but even today he is interesting and appeals to a larger public.”

In a recording left for his last companion, Sylvia Jeanjacquot, who was with him in the car when he died, Mesrine said: “If you are listening to this cassette, it’s that I am in a cell from which there is no escape.”

The letters are on show from 2 November at Salle Baron Ribeyre, 3 rue de Provence, 75009, Paris until the sale on 23 November.