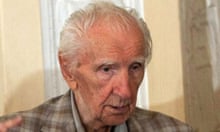

Jacques Vergès, who has died aged 88, was one of France's best known and most controversial lawyers. He was nicknamed "the devil's advocate" for defending "indefensible" clients from the Nazi war criminal Klaus Barbie to the Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic, whom he advised, and, briefly, Saddam Hussein.

The charismatic and provocative barrister's client-list read like a Who's Who of 50 years of international terrorism and armed resistance – from cafe-bombings to plane hijackings and hostage-taking. He was famous for his impassioned courtroom denunciations of colonialism. Often likening the justice system to the theatre, in later years he also gave his performances as a Paris stage show.

Both respected and reviled, he said a lawyer's duty to defend was like a doctor's duty to treat. He argued that all accused, no matter the depths of their crimes, must be understood and empathised with in order to avoid history repeating itself. In 1987, he used the trial of Barbie, the Gestapo figure known as "the Butcher of Lyon" to denounce all forms of "colonialism". He told Barbie, who was later convicted of 341 charges of crimes against humanity, that he wanted people to see his "human side". Vergès's defence of Barbie was typical of the lawyer's many paradoxes: he was a former French resistance fighter who was now acting for one of the most notorious Nazis. He had launched his career defending Algerian independence fighters tortured by the French, yet he was now defending a Gestapo chief torturer.

He defended Magdalena Kopp of Germany's Red Army Faction, who had been caught in Paris with explosives and who he was rumoured to have fallen in love with. Briefly he also acted for her boyfriend Carlos the Jackal – Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, the Venezuelan who had made a career out of bombings, kidnappings and hijackings. More recently Vergès defended the former Khmer Rouge head of state Khieu Samphan, arguing that the deaths of up to 2 million Cambodians in the 1970s did not amount to genocide.

In 2008, as he sat in his office in his rented Paris mansion puffing his trademark cigars surrounded by works of literature and ornamental gifts from his international clients, I asked him whether he would have defended Hitler. He smiled: "I'd even defend George Bush. But only if he pleads guilty."

Vergès furiously denied being "born angry", but his childhood experiences defined him. He was born in Thailand in 1925 – although the date has been disputed – to a Vietnamese teacher mother and a French father from the Indian Ocean island of La Réunion. His father had to quit as French consul because interracial marriages were not allowed by the French authorities.

Vergès grew up there. His mother died when he was three but he inherited from her his fierce sense of the anti-colonial struggle and outrage at non-white people having to step aside in the street. He told me that he never saw her dead: "I just felt a grave atmosphere at home and they wouldn't let me into the room she was in."

He lost contact with his Vietnamese family and was left with only a handful of his mother's objects – her jewellery and her turban. He would later make long trips across the world, in China and Asia, but not Vietnam.

Of mixed race and having what he called a "split personality", pulled between Europe and the developing world, he said he was always trying "to compensate for that absence". It was from his mother that he inherited what he called "the subject that obsesses me – humiliation. I hate to see someone humiliated."

In 1942, he volunteered to serve in General de Gaulle's Free French Forces, travelling first to Liverpool and then to mainland Europe for the French resistance. Later, at the University of Paris, where he studied humanities and eastern languages, his contemporaries included Pol Pot, who would become head of the Khmer Rouge. Vergès briefly joined the Communist party and was a leader in the anti-colonial student movement.

In 1957, less than two years after qualifying as a Paris lawyer, he found fame defending the FLN, Algeria's National Liberation Front, who were struggling against French colonialism, and whose bombs – planted in cafes and bars – set the tone for world terrorism for the next half century. He fell in love with his client Djamila Bouhired, who was tortured and sentenced to death for her role in planting bombs in Algiers cafes. Eventually she was freed, and in 1963 became his second wife, though they later separated.

In Algeria, Vergès first used his trademark strategy of legal "disruption", challenging the French colonial judges on every point, including their very presence, until "no dialogue is possible". It worked in appealing to public opinion but saw him briefly suspended from the Paris bar. He took Algerian citizenship and rose to prominence in the Algerian foreign affairs ministry.

But then, in 1970, Vergès mysteriously disappeared for more than eight years. In 1979, he resurfaced and renewed his Paris law career, never offering an explanation for what he called "my holidays". In a 2005 interview, he said only that he had been "very much to the east of France". Rumours, which were never confirmed, ranged from a possible stint in Cambodia advising Pol Pot to training as a KGB spy or a tour of Palestinian training camps in Libya, Yemen or Jordan.

In the 1980s, he went on to defend members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. Vergès insisted on continuing to practise law until the end. He told me: "A trial is a place of metamorphosis. Joan of Arc wouldn't have been a saint without her trial."

He continued to spark controversy in 2010 when he supported Laurent Gbagbo in Ivory Coast. In 2011, he said he was ready to defend Muammar Gaddafi of Libya if necessary. Milosevic, who took his advice, later opted to defend himself.

Vergès talked of surviving an assassination attempt by French secret services in the 1950s and said he was not afraid of death. In a fitting setting for someone described by colleagues and publishers as a consummate literary performer, he died of cardiac arrest in the Paris former bedroom of Voltaire, the Enlightenment philosopher famed for his attacks on the establishment.

Vergès is survived by his son, Jacquou, from his first marriage; and a daughter, Meriem, and son, Liess, from his marriage to Bouhired.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion