Britain's ability to defend itself against an attack from the Soviet Union was so diminished in the late 1970s that the prime minister exclaimed: "Heaven help us if there is a war!"

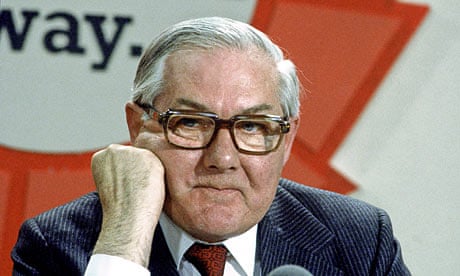

James Callaghan's handwritten note came after he had reviewed top-secret briefings which showed that the country's surface-to-air missiles were equipped with merely a single reload, early warning aircraft were "obsolete" and RAF fighter squadrons hopelessly outnumbered by Soviet bombers.

The bleak assessment of national defence preparations emerged after Callaghan had questioned intelligence reports, according to Downing Street papers released to the National Archives today. He described the situation as a scandal, and called for those responsible to be sacked.

The prime minister's probing at the height of the cold war ignited a fierce debate in Whitehall about the British resources allocated to Nato rather than domestic defence.

The controversy, never made public, originated in October 1977 after the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC) was presented with a detailed top secret report on "Soviet capability to attack targets in the UK base".

The prime minister was not satisfied, however. "I take it someone has worked out whether we can defend ourselves?" Callaghan inquired. His secretary for overseas affairs, Bryan Cartledge, wrote to the Ministry of Defence: "The prime minister has indicated that this assessment gives only one side of the picture.

"He assumes that a similar assessment has been made of our capacity to defend targets in the UK base; and we would be glad of an opportunity to see such an assessment."

The cabinet secretary had to admit there was no "mirror image of the JIC assessment in relation to our own capability because our policy is to base the defence of the UK firmly in the collective effort of the North Atlantic alliance".

Fred Mulley, the defence minister best remembered for dozing off beside the Queen during an official review of the RAF, was scrambled to prepare an explanatory paper. His report admitted that the picture painted by the chiefs of staff was "a sobering one".

"The most immediate Soviet conventional threat is from heavy and medium bombers and long-range tactical," the MoD report revealed. "Against a threat of more than 200 Soviet bombers we have a frontline strength of less than 100 fighters together with very limited area coverage of surface-to-air missiles.

"Although the [Phantom] fighters could acquit themselves well, they have sufficient missiles for only two to three days' operations." A shortage of Bloodhound surface-to-air missiles, which protected 15 key RAF and US airfields, meant they had only "a single reload". As for surveillance, there was a "single squadron of obsolete [Shackleton] airborne early warning aircraft".

The Warsaw Pact nuclear threat involved 150 land-based missiles targeted at the UK and 160 bombers capable of carrying nuclear weapons. Dismayed, Callaghan said: "I wish to talk to Mr Mulley about this."

The conversation at No 10 in February 1978 was grim. "The prime minister said the conclusion he drew from the paper was that one or two people should be sacked (he did not include Mr Mulley)," a note-taker recorded. "He would like to know the cost of remedying the situation and how far it could be met within the existing budget."

Fred Mulley, the defence secretary, tried to recover the initiative by announcing he was to buy "66 secondhand [Bloodhound] missiles with spare parts from Sweden for £6m and [maybe] another 50 from Singapore".

The foreign secretary, David Owen, suggested adjusting "the Tornado programme so as to produce 50 more Air Defence Variants for use in the UK air defence region … and 50 less for long-range strike on the central front".

Sir John Hunt, the cabinet secretary, was alarmed. "Any move on our part to put distinctly more emphasis on the UK at the expense of our contribution to the central front would almost certainly be opposed by [Nato] as a whole and by the US in particular," he warned Callaghan.