Few writers achieve the lucrative double of writing an international hit play that becomes a big-budget movie. Remarkably, though, Peter Shaffer achieved the feat in three successive decades: with The Royal Hunt of the Sun in the 1960s, Equus in the 70s and Amadeus in the 80s. Amadeus became one of the few theatrical sensations to be even more successful in cinemas, with Milos Forman’s adaptation winning eight Oscars in 1985.

Shaffer’s share of the profits from these projects made him the most financially rewarded English playwright of the second half of the 20th century, although – perhaps partly because of his box-office record – the dramatist found it harder to achieve critical and academic approbation.

Peter Hall, who directed Amadeus on stage, even suggested in his published diaries that the play, in which the mediocre composer Salieri is undermined by the arrival of the genius prodigy Mozart, was autobiographical. Mozart stood for a playwright of instinctive genius, such as Samuel Beckett or Harold Pinter, in comparison with whom Shaffer considered himself to be a plodder.

Whether or not this was true, Shaffer’s plays were better and more original than Salieri’s compositions; certainly, though, he was not a writer to whom plays came easily. Whereas the texts of Pinter and Beckett were premiered pretty much as typed, Shaffer’s were sculpted and shaped with the director, before and during rehearsals, from vast piles of overlong drafts. The usually courteous Paul Scofield exploded, when the writer arrived with yet more new speeches close to the opening of Amadeus: “I am not learning another single line!” Even when a show was a hit, the revisions continued. The first and second published editions of Amadeus have almost completely different second acts.

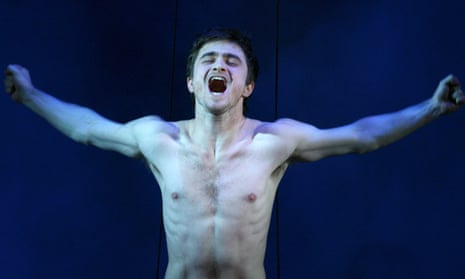

This lack of confidence in what he had written partly explained the falling-off of his career. Although the earlier sensations were revived – Daniel Radcliffe co-starring in Equus in 2007 – no new stage play was performed during the last 23 years of his life, although he confided to interviewers during that period that he was working on two, including a drama about the widows of famous composers.

Another limitation on Shaffer’s reputation was a sense of thematic repetition. Set during the Spanish conquest of Peru in the 16th century, The Royal Hunt of the Sun explored man’s desire to worship gods. Equus, inspired by a friend’s recollection of a real-life case in which a stable boy blinded a number of horses, set a secularist psychiatrist against a teenager whose social and sexual confusions had led him to construct a perverted personal religion around horses. In Amadeus, the court composer Salieri, a faithful Catholic, is horrified to see the divine gift of musical genius granted to Mozart, an obscene libertine. By then, some critics were complaining that Shaffer had effectively dramatised the conflicts of God v Man and Apollo v Dionysus in three different settings.

Those settings, though, were the point. The ideas – and even the words – in his major plays were to some extent incidental. First with John Dexter as director and then Hall, Shaffer created a theatre of grand visual and gestural spectacle. He was responsible for the second trickiest stage direction after Shakespeare’s “Exit, pursued by a bear” when he typed, in The Royal Hunt of the Sun, the line: “They cross the Andes.” “Fancy!” the theatrical impresario Binkie Beaumont is supposed to have exclaimed after reaching that instruction in the script and deciding to reject it. But the sentence was evidence of Shaffer’s conviction that theatre could and must match cinema for pictorial ambition.

Dexter’s production of The Royal Hunt of the Sun – designed by Michael Annals – created a Technicolor theatre that included a huge, metal, petalled sun hung above the stage, actors in golden masks and a vast, unfurling scarlet carpet that represented a bloodbath. The Andes were also, in mime, crossed. What seemed to be a staging impossibility in Equus – the convincing presentation of horses – was achieved through the precise equine movement and noises of actors wearing chestnut-coloured tracksuits and wire-and-leather heads and hooves designed by John Napier.

The grand rhetoric and visual spectacle of The Royal Hunt of the Sun and Equus had been pejoratively called “operatic” by some critics. Amadeus must be as close to a spoken opera as theatre has come. Shaping words into fugues and arias, the text resembles a libretto, while designer John Bury’s representation of 18th-century Vienna had a gilded grandiosity more common at the Royal Opera House than the National Theatre.

Although Shaffer was often categorised as a “commercial” writer, the paradox was that his three most successful plays could only have been created with the resources and time available in subsidised venues; he also benefitted from the presence of a company of actors used to playing big, loud roles in the classical canon.

Apart from the riches his production provided for the eyes, the other key to the Shaffer brand was that he wrote modern roles allowing great Shakespearean actors to use every note of their vocal instruments. In the three major plays, there is always at least one moment when the main character is given a page-long soliloquy. A highlight of the National Theatre’s 50th anniversary celebrations was an archive recording of Paul Scofield delivering one of Salieri’s rants against the God that had betrayed him. When Scofield declined to take the play to Broadway, another National and RSC stalwart, Ian McKellen, took over, while the part of the psychiatrist in Equus was played by a succession of heavyweight names including Alec McCowen, Anthony Hopkins and Richard Burton. On the rare occasions when Shaffer wrote female leads, they were played by Dames Judi Dench and Maggie Smith.

Shaffer’s trilogy of theological and historical epics at the peak of his career was a surprise because he had started as a provider of domestic dramas and light comedies, starting with his 1958 debut Five Finger Exercise.

The dramatist admitted that its portrait of a sexually confused young man serving as tutor to a wealthy English family was emotionally autobiographical. Shaffer was gay, although belonging to a generation of writers who, even after the removal of the legal jeopardy to homosexuality, neither wrote about the subject directly nor spoke about his private life in interviews, although, when the theatrical voice teacher Robert Leonard died in 1990, he was recorded in the New York Times’ obituary as “the companion of the playwright Peter Shaffer”. Some friends and colleagues considered it significant that Shaffer’s public playwriting career ended, soon after Robert’s death, with The Gift of the Gorgon (1991), a grief-stained piece about a playwright obsessed with the classics who loses his marbles in Greece.

Shaffer’s identical twin brother, Anthony, wrote Sleuth, a 1970 whodunnit that ran for several years in London and on Broadway. In a conversation with Hall, quoted in his diaries, Shaffer refers to the instinctive competitiveness of twins – both men were tetchy when confused theatre-goers complimented them on the work of the other – and the obsession in Peter’s plays with internal and opposing dualities seems likely to have been encouraged by his sibling situation. The boys were born in Liverpool, although neither could ever plausibly have been regarded as a Liverpudlian writer. Their shared passion for theatre might be attributed to a prep school teacher who told what they later realised to be the plot of Hamlet in instalments on Friday afternoons, ending on a cliffhanger that left the boys eager all week to hear the next scene.

After three years as a “Bevin boy” – one of the young men conscripted to work in the mines during the second world war – Peter went, alongside Anthony, to read history at Trinity College, Cambridge. In the early 1950s, three detective novels were published under the pseudonym “Peter Anthony” – including The Woman in the Wardrobe and Withered Murder – with the first written by Peter alone and the latter by the brothers in collaboration.

On either side of The Royal Hunt of the Sun, he wrote two comic double bills: The Public Eye / The Private Ear (1962) and Black Comedy / White Liars (1967). Of these Black Comedy, still much performed in schools, is a sublime comic idea in which the usual rules of theatre lighting are reversed: when we can see the characters, they are behaving as if in darkness, but, when the lights are out, they act as if we can see them.

During the decades of the grand rhetorical dramas, some friends of Shaffer tried to coax this lighter side out of hiding. Lettice and Lovage (1988), a comedy about two friends who wage a campaign against modern architecture and other manifestations of contemporary “mediocrity”, is dedicated to a colleague “who asked for a comedy”. Yet even this expert middlebrow entertainment – which ran for two years in the West End and a year on Broadway – dealt in stark dualities between characters and concepts: in this case, conservatism v modernism. So too had its much less successful predecessor, the Bible-derived Yonadab (1985), which marked the last of Shaffer’s four grandiloquent examinations for the National Theatre of man’s desire for the divine and delivered his first flop there.

Shaffer once said, during rehearsals for The Royal Hunt of the Sun, that he realised that “it was my task in life to make elaborate pieces of theatre”. He spectacularly – in every sense – fulfilled that pledge.