Grand Theft Auto IV, the radio series of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy and the Who have one thing in common; one composer, in fact – the visionary musician, improviser and creative-consciousness-expander who is Terry Riley. In fact, it's one album in particular that creates this strange cross-cultural Venn diagram: Riley's A Rainbow in Curved Air, a piece he released in 1969. It's music of still-inspirational and frankly feel-good electronic and overdubbed radiance, made from Riley playing, improvising and re-recording all the instrumental parts you hear in a mind-bending 18 minutes. Riley says that a good friend of his was running the lighting for the Who's shows, "and he turned Pete Townshend on to A Rainbow in Curved Air. The Who song Baba O'Riley was dedicated to both me and [Indian guru] Meher Baba. Pete has always said that I had a big influence on him." Listen for yourself here: Riley's impact on Townshend could hardly be clearer when you hear Baba O'Riley's keyboard riffs and delays.

By the late 60s, Riley was already celebrated in experimental musical circles. In fact, since 1964, the Californian-born musician had become a cult figure on the west coast scene. That's because in November that year saw the first performance took place of In C, still Riley's most famous work, and variously heralded as the first masterpiece of minimalism and the work that ushered in a new musical era, after which the world was never quite the same. Some of that may have turned out to be true, but when Riley came up with In C on a bus ride in San Francisco, it was a piece that was important to him for different reasons. The work crystallised his musical thinking up to that point (as Keith Potter reveals in his book Four Musical Minimalists): his interest in improvisation – already cultivated thanks to collaborations with Pauline Oliveros, Morton Subotnick and others – and his love of John Coltrane and Miles Davis. In C also reflected and refracted the inspiration of the repetitive musical structures he had heard and loved in north African music. It was written as a piece that was defined by the interactions between the members of a diverse group of musicians and which would be different in terms of duration, structure and tempo every time it was played. And, like so many of the greatest musical breakthroughs, In C is simple to understand, but rich, subtle and diverse when you hear it performed.

In C's score is made from 53 musical modules, fragments of musical material and melodies (and not all of them in the key of C either. As the piece progresses, different waves of pitch-centres and modalities are cycled through.) The players move steadily through the fragments, although they can omit them as well, and the modules can be played faster or slower than they're written, accompanied by an ever-present chiming octave C in a piano or mallet instrument. (The idea for that time-keeping piano part could have been Steve Reich's, who, along with Oliveros and Subotnick, was part of the ensemble who played the piece for the first time at the San Francisco Tape Centre.) How many times each is repeated, and how long a performance lasts, will vary each time the piece is played by different forces: it's possible to race through it in 20 minutes, or to luxuriate in it for an hour and a half.

Part of In C's notoriety is that it also seems to embody the hippy-ish sensibility of west coast America at the time, and to evoke a trippy, blissed-out state of musical mind. (On his own use of drugs, Riley told William Duckworth that LSD was "the element of the consciousness-raising movement … [with] marijuana as a sister drug … It had a lot to do with those times, you know. There was something emerging then that people were hungry for: almost as a public at large, especially young people. I know we weren't interested in making money. We were really only interested in having these mystical experiences.") But that's to miss the point of In C's musical qualities, and its subtly brilliant answer to the conundrum of how you create a piece that simultaneously empowers its performers and insists that they listen to each other and take responsibility for the performance as much as the composer, but which is also always essentially itself, a piece that cannot be mistaken for any other. In C does that brilliantly. Along with Cardew's Paragraph 7 from The Great Learning, it's as elegant and beautiful a solution as there is.

But In C is also nearly 50 years old, and Riley's life in music is still a continual search for the fundamentally spiritual qualities that he believes the art form should embody. In 1970, he started to study with Indian vocal master Prandit Pran Nath and his musical activity since then has evolved a fluid exchange between improvisation and composition, between aspects of jazz, Indian music and classical structure. He has even created of a sort of contemporary music of the spheres – you can hear the uniqueness of Riley's musical 'interzone' in the keyboard imagination and virtuosity of Persian Surgery Dervishes and Shri Camel, with their hypnotic mix of unusual tunings, modalities and rhythmic invention. The only connection with "minimalism" on these records is Riley's continuing interest in exploring different kinds of repetition. Otherwise, his range of sources and his musical-mystical ambition are far from the process-based austerity of early Steve Reich or Philip Glass.

Riley's association with violinist David Harrington, who went on to found the Kronos Quartet, has been the inspiration for a series of works (more than a dozen so far) that led Riley back to more conventional kinds of composition; conventional at least in the sense of how they are notated and performed – but not in how they sound. Salome Dances for Peace is a sensuous but epic 100-minute cycle for string quartet; Sun Rings is an even bigger set of pieces for quartet, choir, visuals and the sounds of space. Literally: the piece uses Nasa's captured sounds of the spinning planets to inspire a sonic meditation on our place in the cosmos.

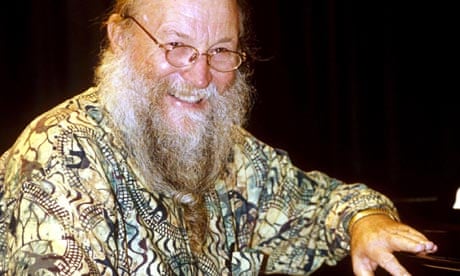

With much of Riley's more recent music and performances, you need to be ready to be taken into a different way of being when you listen to them, to accept the combination of gentleness, naivety and sense of wonder that radiates through his work. For Riley, his instrumental virtuosity and his compositional imagination are the gateways to the exploration of a global musical consciousness. Enjoy your journey into the world of Riley – just believe the beard.

Five key links

In C

Shri Camel

Salome Dances for Peace

Persian Surgery Dervishes

A Rainbow in Curved Air

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion