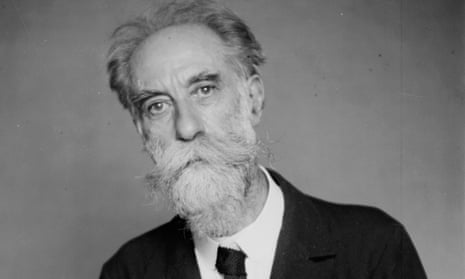

Charles Koechlin’s huge output includes examples of almost every orchestral, instrumental and vocal genre; opera is the only significant omission from a work list that runs to well over 200 opus numbers. Among that wealth of music, much of it still seriously undervalued and underperformed, there are no less than 29 works for flute, an instrument that was particularly prominent in French music around the turn of the 20th century, and for which Koechlin seems to have retained a particular fondness throughout his life.

By far the most extensive of his flute works are the three collections, his Opp 98, 99 and 100, composed in 1944 under the title of Les Chants de Nectaire, 96 unaccompanied pieces altogether. Nectaire is a character in Anatole France’s novel La Révolte des Anges, an old shepherd and philosopher who entertains his friends by playing a wooden flute. Koechlin’s pieces, none lasting as long as five minutes, and most considerably shorter, are exquisite, wonderfully varied examples of his fondness for monody. Each piece is perfectly distinct and shaped, evoking a lost pastoral world that may or may not ever have existed, in music that ranges from archaic modality to intricate chromaticism and may be languorous, playful or nostalgic.

I wouldn’t suggest listening to the whole of Les Chants de Nectaire in a single sitting – nearly three and a half hours of solo flute might be too much of a good thing for even the most devoted woodwind enthusiast. But sampled more judiciously the pieces are a quiet delight and it’s a measure of how they are valued by flautists that this is at least their fourth complete recording, one of them, released in 2007, by one of the greatest contemporary players, Pierre Yves Artaud. These performances by Nicola Woodward are intensely rewarding too, though, with all the suppleness, refinement and easy expressiveness such jewelled miniatures need.

This week’s other pick

Though their careers in French musical life overlapped considerably, there was little common ground between Koechlin and Camille Saint-Saëns – the former an instinctive, lifelong radical, the latter a convinced conservative who often regarded the music of his younger contemporaries with distaste. Saint-Saëns’ copious output is certainly not as neglected as Koechlin’s, but a lot of it is only rarely heard, especially his chamber music. The Erato collection of sonatas for violin and for cello, together with the second of the piano trios, all played with a real belief in the music’s quality by violinist Renaud Capuçon, cellist Edgar Moreau and pianist Bertrand Chamayou is a reminder that there are treasures to be unearthed there, too.

Saint-Saëns: Sonates & Trios is released by Warner Classics/Erato on 27 November.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion