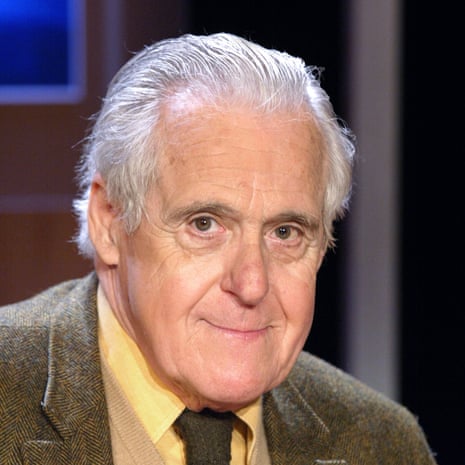

In 1969, Christian Millau, who has died aged 88, founded with his business partner, Henri Gault, a monthly culinary magazine, Le Nouveau Guide Gault-Millau. Three years later it became an annual guide – Gault & Millau – and challenged the supremacy of the red Michelin guide to the restaurants of France.

The pair had spotted a tendency among younger French chefs that they baptised nouvelle cuisine. Departing from the traditional cuisine codified by Auguste Escoffier, the new chefs shunned flour-based sauces and long cooking times, favouring reduced pan juices, vegetables that retained some bite, flash-cooked meat and fish, an appreciation of novel ingredients and technique, and – notoriously – smaller portions.

The leading chefs of the movement included the Troisgros brothers, Michel Guérard, Alain Chapel and a dozen others, though Paul Bocuse, really more a traditional cook, became known as the leader of the pack. Chefs suddenly became household names and, from being a working-class vocation, it started to recruit its members from the middle classes.

The man who kickstarted this revolution was born Christian Dubois-Millot in Paris, the son of Paul Dubois and his wife, Anne (nee Masur), a Russian émigré. He assumed his pen name when his byline first appeared in 1949 in Le Monde, for which he was a political reporter, having studied at Sciences Po, the Paris institute of political studies.

He then worked for the literary review Opéra, edited by Roger Nimier, whom Millau featured in his 1999 book Au Galop des Hussards: Dans le Tourbillon Littéraire des Années 50 (The Hussars at Full Speed: In the Literary Whirl of the 1950s). “Les Hussards” was a rightwing movement opposed to the prevailing existentialism, anti-Gaullist and anti-Sartre. Millau’s personal history of it won both the grand prix for biography of the French Academy, and the Joseph Kessel prize, given to “a book of a high literary value written in French”.

Millau had an impish sense of humour. In later years, he published several titles, including the memoir Journal Impoli 2011-1928, for which he received the “politically incorrect book prize”.

His gastronomic writing came after 20 years of mainstream journalism. By 1960 Millau was deputy editor of the evening paper Paris-Presse, responsible for the features pages on which Gault’s Week-end et Promenades articles, including restaurant reviews, appeared. This led to the first Guide Julliard de Paris (1962), and the idea of their joint, independent project took shape.

They were more flexible than Michelin’s system of awarding one to three stars for excellent cooking; instead they employed the familiar French school system of marks out of 20, giving a maximum of 19.5/20, because “only God can achieve 20 and He is rarely to be found at the stove”. Moreover, though the Michelin guides of the time used only symbols, the Gault-Millau boasted paragraphs of crisp French prose, written by them and the French journalist André Gayot.

They deduced some tenets of the nouvelle cuisine from what the young chefs they highlighted were doing, using them to distill the 10 commandments. These circulated widely, and greatly influenced chefs in the US and UK, such as Charlie Trotter, Jeremiah Tower, Thomas Keller, Anton Mosimann and Raymond Blanc.

Interviewed by Le Figaro in 2014, Millau said his team and Michelin’s “had never been adversaries, as Michelin gave its stars for seniority, much as the Third Republic bestowed medals on good workers”, and then “caught up with some chefs (Bernard Loiseau, Guy Savoy, Michel Guérard, Michel Trama, Alain Senderens, etc) 10, 12, even 15 years later than Gault-Millau, whose speciality was discovering talent”.

The title was sold to the magazine Le Point in 1983, the two founders split up in 1985, and Millau ran the guide for a further seven years before handing over to others. By the arrival of the new century, the internet was reinforcing the power of ratings for all sorts of products, giving authoritative guides the power to transform the fortunes of businesses and their owners.

When Loiseau took his own life in 2003, it was speculated that the threatened loss of a Michelin star and a downgrading from 19 to 17 in Gault-Millau for his restaurant in Burgundy had contributed significantly to the pressures he was under.

Such focusing of purchasing power would not have occurred to Millau in the simpler age when he embarked on trying to raise standards and awareness. Once, dining in a smart Paris restaurant with him, I noted he was greeted warmly by many of the staff. Didn’t he think reviewers ought to be anonymous, I asked? “Ridiculous,” he replied. “It’s impossible for me to be incognito, and, anyway, what can a restaurant do if they do recognise me? The ingredients have already been purchased, the recipe is fixed and the menu written. The chef can only cook his best, the maître d’hôtel can only give me a better table, and the waiters smile more than usual.”

And why, I asked, did he think nouvelle cuisine needed to be invented? “Central heating and the internal combustion engine. Humans no longer need the same number of calories just to stay warm and get to their work.”

On another occasion, at lunch at Joël Robuchon’s Paris flagship restaurant in the early 80s, while telling me about his recent trip to America, he impulsively decided it would be a good idea to introduce the concept of the “doggy bag” in France. He summoned our waiter, but then spotted a nominal difficulty. “I can’t quite finish my fish,” he said of his tranche of turbot. “Could you please wrap it up for me to take home to the cat?” Unfazed by the request, the waiter returned from the kitchen carrying a boat-shaped, foil packet with curving ends that formed an elegant handle. Millau was engagingly miffed at this evidence that, whatever it was called, he was not the first to ask for it.

In 1959 he married Arlette Conrad. She died last year. Millau is survived by a daughter and two sons.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion