Cuyahoga Falls is a middle-class suburb of industrial Akron, Ohio, a grid of leafy streets and comfortable homes bordered by the river. When Jim Jarmusch was a boy, he knew to steer clear of the water because, while the town might be placid, the Cuyahoga river was toxic. Pickling acids had stained it bright orange. Factory detergents had put a white froth on its surface. In June 1969, a spark from a train set the Cuyahoga alight and the flames jumped as high as a five‑storey building.

Fifty years on, Jarmusch remembers it well. “It was not a pleasant thing to happen,” he says with the droll understatement that has become his signature style. “In fact, if you’re looking for a metaphor of modern American life, it doesn’t get more blatant than having your local river catch fire.”

As a film-maker, Jarmusch likes to make movies about the world’s little details; about drifters and seekers and the rambling detours that add up to a life. It’s an area of interest that has served him well, from 1984’s meandering, monochrome Stranger Than Paradise through to 2016’s soulful, meditative Paterson. But it’s hard to focus on the small pictures when the big one is so scary: when a river is burning or the whole planet’s aflame. He says: “It’s clear we’re living in an ecological crisis and the situation is getting worse and worse. We’re threatened by the denial of science and by corporate greed. If this is the path that we keep going down, then it is only going to lead to the end of the world.”

I first run into Jarmusch on the backstreets of Cannes in May this year, where his latest work, The Dead Don’t Die, opens the film festival as climate crisis protesters gather beside the Palais. A few weeks later I speak to him again on the phone at his house in upstate New York. He explains that while he maintains a bolt-hole in his adopted Manhattan, these days he prefers living out in the Catskills. He shares the house with his partner of four decades, the actor and film-maker Sara Driver. “This is family time,” the 66-year-old says. “I guess you could say I’m up here to recover.”

The alternative view is that he’s hiding out in the woods; the silver fox of independent cinema lying low, gone to ground. If the apocalypse is pending, The Dead Don’t Die shows the way it might go, with polar fracking warping the planet’s axis, Trump-supporting racists spinning on their bar-stools, and an army of zombies shuffling up main street. Jarmusch keeps referring to the film as a comedy – pretty funny, plenty of jokes – but his sales patter carries a plaintive note. He knows the film is not as frothy as he meant it to be.

He sighs. “The tone is different from what I anticipated. It’s a whole lot darker than I imagined, especially the ending. I try not to analyse these things too much, but that’s reflective of the world we’re in; the looming environmental crisis just became more and more of a cloud. I was working on this film for two years, and during that time it was as if the planet was changing on an almost daily basis.”

Small wonder that the finished movie pulls in different directions and seems almost at war with itself. The tale sets forth as a jaunty, knowing deconstruction of the zombie genre, only to be caught in the crossfire of fatalism and despair. “This whole thing’s going to end badly,” warns Adam Driver’s small-town cop as the walking dead descend on Centerville, calling out for coffee and wifi, chardonnay and Xanax. The cast’s an amiable ragbag of Jarmusch’s buddies and collaborators. There’s Bill Murray, Tilda Swinton, an undead Iggy Pop. Tom Waits co-stars as Hermit Bob, a rackety old recluse who lives in the forest and survives on squirrels and bugs. He knows what’s coming and accepts it with a shrug. “The world is fucked-up,” he informs us at the end.

The film was shot near Jarmusch’s home, around the neighbouring towns of Kingston and Fleischmanns. This ought to have made the production simple, but somehow did not. The schedule was a nightmare; they only had Driver for three weeks. On top of that, it rained constantly. The director came down with the flu and broke a toe on the set. “And then we had to rush to get the thing finished so that we could give it to Cannes.” I have the sense that he’s still trying to figure out what he’s made. “I mean, I wouldn’t have changed the film at all. But I would probably have had more time to think about just what I was doing. It slipped out of my hands like a little child on the riverbank.”

As a kid back in Akron, Jarmusch dreamed of slipping away, too. The place was too small, too conservative. Everyone worked for the rubber companies: his dad for BF Goodrich, his uncle for Goodyear, his neighbour for Firestone. His mum, Betty French, had been an arts reporter for the Akron Beacon Journal. She reviewed the young Marlon Brando in the Broadway production of A Streetcar Named Desire and covered the Hollywood wedding of Bogart and Bacall. But when she got married, she jacked in the day job and tucked herself away in a small upstairs office at home. Jarmusch remembers the sound of her picking away on an old Royal typewriter, turning out freelance articles for a local antiques magazine.

He credits his mother for sparking an early interest in art, music and film. But he also drew inspiration from a more lurid source. The “ghost-host” Ghoulardi was a costumed presenter who introduced B-movies on Cleveland’s JWJ-TV station. The Dead Don’t Die contains a Ghoulardi poster in homage.

“Well, he was a really important cultural figure,” Jarmusch explains, deadpan. “He had a TV show on Friday nights at 11.30 where he would show sci-fi, horror or monster films – mainly monster films. And he did all kinds of crazy stuff in between. He was this beatnik kind of guy with a goatee, dressed in a white lab coat with a fright wig, dark glasses with one lens missing. He used a lot of hipster catchphrases that were all made up. He’d explode model cars with cherry bombs and he had this early kinescopic effect where he would briefly place himself inside the film he was showing. So yeah, if you ask anyone who grew up in north-eastern Ohio in the 60s, we’re all familiar with Ghoulardi and his influence on us. I think Chrissie Hynde still has her original Ghoulardi T-shirt.”

He pauses. “You know who Ghoulardi’s son is, right?” As it happens, I do. Ghoulardi was played by a TV announcer called Ernie Anderson who would later father Paul Thomas Anderson, the director of Magnolia, Boogie Nights and Phantom Thread. “I’ve only met Paul once, and the first thing I said to him was: ‘Your dad was Ghoulardi!’ He kind of rolled his eyes about it, but I mean, come on, that was my young bohemian dream – a weird dad like Ghoulardi.”

Except why stop with Ghoulardi? Jarmusch is a pop-culture sponge. He soaks up pretty much everything and likes to quote Joe Strummer’s old motto: “No input, no output.” His films are made up of secondhand odds and sods, twisted to fit his own sensibility, possibly his own image. I tell him that they’re distinctive and stylish, sometimes to a fault.

“Well, style is very important,” he says, unperturbed. “It’s what Martin Scorsese says differentiates all film-makers. Style is the important identifier of someone’s personal expression.”

Hitchcock once said that drama is life with the dull bits cut out. But Jarmusch’s films seem expressly designed to test that maxim, turn it upside down. They glide over scenes that might form the centrepiece of a more conventional picture and salvage incidentals from the cutting-room floor. On his 1986 breakthrough, Down By Law, he rustled up a jailbreak drama that ignored the jailbreak. On the 1995 western Dead Man, he took a perverse delight in finding the most humdrum locations in Oregon and Arizona. At their best, his pictures are ruminative and poetic all-American stories that move with the unhurried pace of Asian arthouse cinema, or postcards from obscure places, complete with doodled footnotes. Reviewing 1989’s Mystery Train, Roger Ebert wrote: “The best thing about the film is that it takes you to an America you feel you ought to be able to find for yourself if you only knew where to look.”

Naturally, Jarmusch says, the films are a reflection of him. “I know I have a laconic approach, time-wise. I know I talk kind of slowly. I probably think kind of slowly. I like slow music. I like slow films. That’s just inherent. Godard said that every film-maker makes the same film over and over. That’s probably true in my case.”

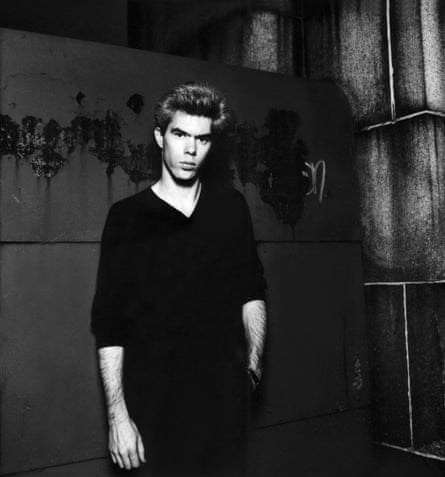

Let’s talk about his personal style. That has remained a constant, too. Jarmusch’s hair began to whiten when he was in his mid-teens, round about the time that the Cuyahoga caught fire, with the result that he barely seems to have changed over the ensuing half-century. Compare a picture from the 80s with the Jarmusch of today and it’s hard to spot the difference. He has the same fine, handsome features, the same space-age quiff, the same dark charisma. In photographs, whether intentionally or not, he always appears to be striking a pose. It’s as though he views himself as a frontman for the pictures that he makes.

But the suggestion makes him snort. The surest way to prick his aura of pristine cool is to ask about his aura of pristine cool. “I find that a ridiculous idea,” he says. “My personal style, how I look and dress – I don’t consider that to be a part of my art. It reminds me of when I was starting out and people would say: ‘Oh my God, he wears black clothes and dyes his hair white and he makes black-and-white films. What a pretentious asshole.’ Whereas none of these things was related to me. My hair was prematurely white. I started wearing black as a teenager because I liked Zorro and Johnny Cash. And then suddenly in New York it was like: ‘Oh, he’s a hipster.’ That’s just hilarious to me.”

He thinks it over. “I mean, I suppose I’ve always thought from when I was a teenager that how you look and how you dress must reflect something about you. But I paid a lot more attention to it back then, when I was in Ohio, than I do now, because I just kind of stuck with it. I haven’t really changed.”

When he first landed in New York, he wanted to be a poet or a musician, whichever came easier. More than anything he wanted to immerse himself, reinvent himself, put as much distance as possible between himself and Akron. It’s tempting to compare him to Andy Warhol, another escapee from the rust belt, or F Scott Fitzgerald’s Jay Gatsby, a gorgeous series of successful gestures. Actually, he says, Manhattan at the time wasn’t much prettier than Cuyahoga Falls with its poisonous river. This was 1977, the year of the blackout, the Summer of Sam; graffiti sprayed across the subway cars and the entire city on the verge of bankruptcy. But it was also a good time, a creative seedbed; the streets thrumming to the crosstown traffic of hip-hop and punk-rock.

“It was dirty, it was dangerous. It was everything I’d dreamed of. And you’d go out at night, and yes, you’d see Andy Warhol. You’d see Ornette Coleman walking by, carrying a fucking horn case. I met [experimental film-maker] Jack Smith on the street and he was pushing a baby carriage full of garbage for one of his shows. He gave me a business card that said: ‘Jack Smith – exotic theatrical genius.’ I met Nico on the street and she invited me to come and have tea with her at the Chelsea hotel. It was…” He can’t get the words out. “It was magical. It was amazing. It was – wow.”

Jarmusch’s early films were about men and women on the move. The fugitives out of Down By Law, the Memphis tourists in Mystery Train, the taxicab passengers from Night on Earth. Recently, though, his protagonists seem to be slowing down, circling towards rest, like the jaded Detroit vampires from Only Lovers Left Alive. In 2016, he ventured out to Paterson, New Jersey, the former home of the poet William Carlos Willams, to make what was arguably his simplest, most personal picture. Paterson spun the tale of a serene, bus-driving poet who folds the creation of great art into his daily routine. Jarmusch shot the film on location. He dragged his camera past the nail bars, pizza joints, factories and the river. Somewhere along the way, it struck him that Paterson, New Jersey, was a lot like Akron, Ohio – and that in making the film he was, in a sense, coming home.

Paterson garnered some of the best reviews of the director’s career. It was seen as heartfelt and pure; weightless and transcendent. The Dead Don’t Die has prompted a more sniffy response. But that’s OK, Jarmusch insists. He knows his films have a tendency to split an audience. What some see as beautiful and strange others regard as artificial and contrived. He’s given up worrying about being misunderstood.

Jarmusch says: “Here’s the thing: the dilemma for all film-makers. The beauty of cinema is that you’re basically walking into Plato’s cave. You’re going into a darkened room and entering a world you don’t know anything about. You’re going on a journey and you don’t know what to expect.” He pauses. “But if you’ve written the script and raised the money and shot the film and then sat in the editing suite for six months, then you are not going to be able to walk into that world. That experience has been robbed from you. The result is that you can’t see the film that you’ve made. The interpretations of others are more valid than your own.”

Besides, he adds, if you stare long and hard enough at anything, you realise that pretty much every element is contradicted by another. That’s true of every movie; it’s true of every person. “Just look at me. I feel very strongly about the state of the planet. I find the actions of Greta Thunberg and Extinction Rebellion to be very moving. But I’m also making a film that’s intended as genre entertainment. I drive a fossil-burning vehicle. I use credit cards and plastic. So what do I do? Is it only black or white? Am I only part of the problem or part of the solution?” He doesn’t know, he’s at a loss. “I’m not for negativity. I’m not a fatalist. I’m for the survival of beauty. I’m for the mystery of life.”

I ask if he gets back to Ohio much these days and he says he doesn’t – there’s not much reason to visit. His mother died about a year ago; he had to go back then, to arrange the sale of her house. He adds that he still has a few close friends out in Cleveland, some of whom run the Blue Arrow record store. I ask how he feels about New York and he heaves a sigh. Change is good, by and large. He’s not nostalgic by nature. But it’s not the same place he came to as a weird kid with white hair.

“Actually I like it less and less,” he says. “New York gave me so much energy when I was young and I’ve basically been cashing it in ever since. The city is demographically less varied. There are lots of younger people whose values I don’t really understand – I guess they just want to make money and hang out with models. It doesn’t seem to be about expression and art, the way it used to be. Maybe that’s unfair, I don’t know. These days I prefer being out in the woods by myself.”

He’s sounding more like Hermit Bob by the second. Next thing we know, he’ll be eating squirrels and bugs. “Yeah well,” he shoots back. “The world is fucked up.”

The Dead Don’t Die is released in the UK on Friday

Xan Brooks’s top five Jarmusch films

1984: Stranger Than Paradise

Jarmusch set out his stall with a delightfully lugubrious road movie of sorts, which sent three square pegs (jazz musician John Lurie, drummer turned actor Richard Edson, and Hungarian-born Eszter Balint) rattling across America’s round holes. Shot in black and white on a budget of $125,000,the film won the Caméra d’Or award at Cannes and pointed the way ahead for US independent cinema.

1989: Mystery Train

The director’s fascination with US pop culture peaked with Mystery Train, a colourful Memphis portmanteau, paradoxically bankrolled with Japanese cash. The film’s winding course leads from the station to the dive bars to the insalubrious lobby of the Arcade hotel, where Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’s night clerk keeps a baleful eye on the foreign tourists.

1995: Dead Man

The hidebound American western took on a strange and bewitching new form with Dead Man, a tale of manifest destiny turned in on itself, seeing visions on the prairie and sandblasted by Neil Young’s elemental guitar score. Robert Mitchum gave his career swansong as a corroded 19th-century industrialist, while Johnny Depp headlined as wonky William Blake, a runaway accountant with a bullet lodged beside his heart.

2014: Only Lovers Left Alive

Jarmusch confesses that he’s always been more of a vampire man than a zombie fan. He loves their refinement, their beauty, their decadent nocturnal existence. With Only Lovers Left Alive (starring Tilda Swinton and Tom Hiddleston) he laid on a vampire film of his own, gliding around the exotic ruins of Detroit and trailing clouds of glory. Critics, inevitably, were keen to frame it as a thinly-veiled self-portrait.

2016: Paterson

Each day, Adam Driver’s modest young bus driver sets off on his route. Each day, he writes pure, simple poetry inside his notebook. Paterson tells us that routine is important, that small is beautiful and that the creation of art is as natural as breathing. It’s a film that – to misquote William Blake – sees the world in a bus timetable and heaven in the tatty old streets of a humdrum industrial town.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion