A young man walks into a bar and meets Sam Shepard, Christopher Walken and Al Pacino. The man is Tim Roth. The year is 1990, and the actor is in New York to film Jumpin’ at the Boneyard, a bleak movie about drug abuse. Roth, who planned to nurse a quiet beer while watching American football, found himself in conversation with Walken and Shepard. “I thought: ‘What the fuck have I walked into?’” he says. “It was purely by chance.” By the time he left, Shepard had promised to write him a part in his next play. It was not the first time Roth had been in the right place at the right time, and it wouldn’t be the last.

This unlikely encounter took place at a propitious time, just as Roth was starring as Van Gogh in Robert Altman’s Vincent & Theo, and shortly before his comic double act with Gary Oldman in Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz & Guildenstern are Dead hit the festival circuit. Writing in the New Yorker, Pauline Kael described Roth’s acting as “a form of kinetic discharge”. After a decade in which the film industry had largely curdled into a hit machine of bland studio blockbusters, independent film was stirring into life and craft was back in vogue.

Due back in London after filming, Roth instead chose to go prospecting in LA, expecting “to get swiftly kicked out the door”. Like his encounter in a Manhattan bar, serendipity intervened. Its name was Quentin Tarantino, the movie was Reservoir Dogs, and it changed everything.

“He came back to my flat after a night in a bar, and we read every scene with all the characters, had a great time – and he gave me the job,” says Roth. “I was very fucking lucky. I got given a window, and I jumped.” When Shepard, good as his word, called back with a part in his next Broadway play, it was too late. “I couldn’t do it,” Roth says. “I always regret I lost that opportunity.”

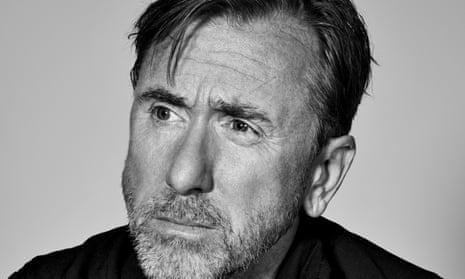

We are sitting on the veranda at the Langham, an old-world, old Hollywood hotel that has been servicing the rich since the 1930s. A sweep of lawn is framed by slender palm trees and the tropical blooms of birds of paradise. Roth grins. “It’s so cheesy, right?” Nearby a large party of women fills a room furnished in leather and burgundy wood, the tables a jumble of three-tiered cake plates and pots of tea. “It’s outside of the Hollywood scene,” Roth explains. “There are people who live around here, but you never see ’em.”

Next summer, the 57-year-old actor can be seen in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, his fifth movie with Tarantino, this one set during the Manson Family murders, and stuffed with stars including Leonardo DiCaprio, Brad Pitt, Al Pacino and Margot Robbie. “I think there’s 100-odd characters in it,” says Roth, though he will not be drawn into discussing details.

In the meantime, there’s Tin Star, a kind of contemporary western set in the Canadian Rockies, and returning to Sky this month for a second season. Roth plays British cop Jim Worth with the kind of shuffling weariness of those who know that bad guys usually win – and reeling from the brutal murder of his son, all while going head-to-head with a mendacious oil company that has sent an executive (Christina Hendricks) to cajole and persuade (and maybe dispatch) troublemaking naysayers.

After so many American roles, it’s a pleasure to hear Roth using his real accent, still unchanged by the decades of California living. Although the city is crawling with Brits now, he says it was different in 1990. “At the time that I came out here there were no English actors, except for Gary [Oldman]. He put the bridge out for me, made it seem possible.”

Roth rarely misses an opportunity to give credit where it’s due, and his heroes and mentors materialise throughout our conversation, like old friends passing through: fellow actors such as Ray Winstone and John Hurt, former teachers, and the writers and directors – Alan Clarke, Ken Loach and Barrie Keeffe – who he credits for giving him a career. Roth is grateful to have grown up in 70s London, when a generation of writers were responding to Britain’s post-industrial decline with visceral social realism. It was a world he was familiar with. Cast as a racist skinhead in Made in Britain he was able to nail the nihilism, anger and violence of white working-class men because he’d had a masterclass in how bullies behave at his Lambeth high school. He recalls daily riots, kids charging in through windows, street battles. “I hated it because I used to get beaten up every day,” he says. “I didn’t know how to fight.”

The bullying grew so bad Roth’s mum moved him to Croydon Tech. “I messed that up, so they sent me back to school,” he says. In the end, he just bunked off altogether. “We’d put on our uniform, throw a change of clothes in our bag, and head up to the West End, which was a dangerous place to be at that age,” he says. “A couple of my mates got lost into that sex trade shit.” Roth managed to avoid that fate, and spent much of his time at the ICA on the Mall. “At that time, it was run by three gay guys, and it was very underfunded, very scruffy, but very, very cool,” he recalls. “They gave us safety, and they talked to us as equals, and they gave us some kind of artistic credibility in our sort of small minds.” Invigorated, he returned to school and flourished. The bullies had left and the atmosphere had changed. “We got to have real conversations about stuff we cared about.”

Punk was on the horizon, mutiny was in the air. Roth organised Rock Against Racism benefits and joined Students Against the Nazis. He dodged rocks on protest marches with his dad. Most importantly, he found his calling, collaborating with a friend on scripts based on a mash-up of the Marx Brothers and Samuel Beckett. “We fell in love with Waiting for Godot,” he says, sheepishly. “I was going through an utterly obnoxious phase.”

He abandoned a place at art college to focus on his acting; there was a lot of angry-young-man stuff by Steven Berkoff and Keeffe in cramped rooms above pubs. Then came Trevor, the swastika-tattooed delinquent in Made in Britain. Watching it now you are aware of Roth’s alert and restless eyes, the insolent smile, the simmering intimation of violence. That it was put out on ITV seems extraordinary today, but perhaps no less so at the time.

The screenwriter David Leland later recalled that the broadcast left people wondering whether their TVs were “plugged in properly”. When Trevor hurls bricks through the windows of Pakistani’s home, yelling “I’m British”, it unrolls like an origins story for the social disintegration that fuelled the referendum result in 2016.

“I understand why the Brexit thing happened because Trump happened in America – I get what’s at the root of it,” he says. “You see the knee-jerk of racism which runs through the whole lot.” He believes our only option is to accommodate immigration. “As a result of climate change, and of economic corruption, there’s a migration system at work. People have got to move – and when the water levels rise they’re going to move even quicker.”

Unusually, his father was the rare migrant who moved from New York to Liverpool. Roth is toying with making a movie based on his story. “He was from Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn, which was really rough at that time, and he had a big and very nasty family,” he says. “They did the reverse thing and got out of the States. When my father was 11, he was working in brick factories in Liverpool, but they persuaded his father to get them out of there so he moved to Kent and was put to work in the hop fields.” By the age of 17, Roth senior was flying with bomber command in the Second World War.

“He was a good man but he was a complete mess because of his life and the war,” says Roth. “One of the last conversations I ever had with him, he asked: ‘Did my dad ever fuck with you?’ I said, ‘Yeah,’ and he said, ‘Yeah, me too.’ The bottom falls out of your world, but it gives you a voice. As messy as your life can be, as completely complicated as anything is, there has to be a window you can climb through, and he gave me that.”

In the midst of the palms and the endless blue of the sky, Roth’s unvarnished delivery of this father-son confessional lands like a sucker punch. Fuelled by his own abuse, Roth’s directorial debut, The War Zone, a movie soggy with rain and despair, explores the impact of incest, its destructiveness, its poison. It’s an astounding movie, shot through with poetic moments of tenderness that make the scenes of sexual violence all the more horrifying. We are not used to seeing monsters portrayed as humans. Roth wanted to show how abusers make their victims complicit in their abuse. “They are directors and you are the actor, you perform it for them, you keep their secret,” he says.

It’s been 20 years since Roth made The War Zone. Has he thought of directing another movie? “I wanted to make sure my kids [he has three sons, one by Lori Baker in 1984 and two by his wife, Nikki Butler] went to school without coming out with a mortgage hanging around their necks,” he says. He has been sitting on a script for King Lear that Harold Pinter wrote for him, and may direct a movie in Mexico based on a novel by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. “The family has given it their blessing,” he says.

And, of course, there’s Tin Star, in which the episodes allow for a lot of collaboration, just the way Roth likes it. “We spent a lot of time, myself and the producer Alison Jackson, working on improvising the dialogue and changing the nature of the story.” Was he worried that a class act like Tin Star would be lost in the crowd of so many other great shows? He was not – that was an old person’s way of thinking of TV. “I track it through my kids and their generation,” says Roth, before giving me a short tutorial on binge-watching. “It’s not television any more,” he said. “It’s something completely different.”

Roth does not expect to live in the UK again, but it’s clear the contours of his working-class childhood still shape his career choices. He plays rich arseholes sparingly. Even his Oscar-nominated turn as the aristo-rapist Archibald Cunningham in Rob Roy operated as a vehicle to illuminate injustice. He says Tarantino gets a kick from writing “fake posh” roles for him, because he can sense his antagonistic relationship to class, a clue perhaps to the kind of character he may play in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.

His relationship to Tarantino has defined his life in the US in more ways than one. He was in Sundance for the premiere of Reservoir Dogs in 1992 when he met Nikki Butler. A year later, the two were in Belize where Roth was filming Heart of Darkness with Nicolas Roeg. “That’s when we got married, in the jungle by the river there,” he says. “We decided to run away and do it on a film set.” Who proposed? “I did. I went and got a tattoo of her initials on my arm and then I went and had a beer with my mate, and went, ‘Right then, we’re off’, and I got back and did the deed. It’s a private story, but she thought I was going to break up with her.” He chuckles fondly. “It was a good one.”

As Roth departs to meet the woman he still calls the “missus”, a group of friends sit beside us and proceed to order margaritas. It’s shortly after 1pm, and the sun is bright and high. The atmosphere is festive. “It’s a weird world,” Roth says in his gruff London accent, but despite this he seems, as always, perfectly placed.

Series 2 of Tin Star begins on Sky Atlantic on 24 January

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion