Twenty years after his death, Stanley Kubrick has never been more popular or visible, particularly in the country he called home for the last 37 years of his life. The BFI Southbank is dedicating a retrospective to his work, his best-known films – including 2001, Dr Strangelove and A Clockwork Orange – have been rereleased, and a touring exhibition drawn from his copious archives is arriving at London’s Design Museum, after stopovers in Frankfurt, Mexico City and Seoul.

Entitled simply Stanley Kubrick: the Exhibition, it is testament to Kubrick’s talent for in-depth research, acquisition of shiny new gadgets for props in his films, and persistence in bending fellow creatives to his will. Here you can find his letters to Saul Bass, badgering him for new versions of the poster for The Shining; a card index for every day in Napoleon’s life, for a film that was abandoned before going into production; and the orange doorless Probe 16 car, only three of which were ever built, that became A Clockwork Orange’s “Durango 95”.

No other film-maker produced masterpieces in a such a wide variety of genres: war movies, political satire, sci-fi, literary adaptation and horror. Allied to this was an unerring ability to create iconic pop-culture moments in almost every film, from “I’m Spartacus” to “Heeere’s Johnny!” Deyan Sudjic, director of the Design Museum and curator of the exhibition says: “He made all these films in a pre-digital era, using analogue techniques and putting them to amazing effect. He used sound, music, acting, architecture and design to create extraordinarily real worlds. As a design museum, we find that fascinating. We try to show how he achieved the magic, but also evoke the magic.”

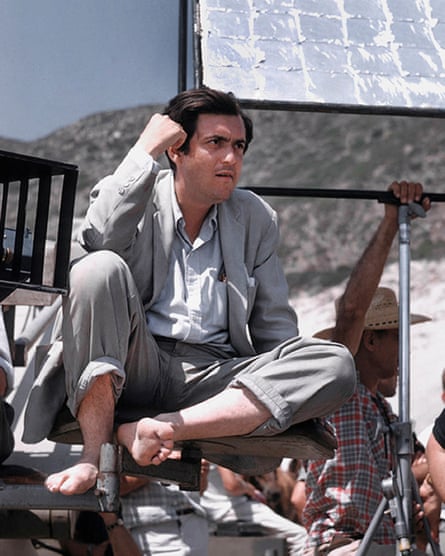

Born in New York to a family of Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe, Kubrick turned a childhood interest in photography into an early career in photojournalism, which then evolved into an obsession with film-making. Without industry contacts, he had to borrow money from friends and relatives to fund his early features: his first, Fear and Desire, Kubrick considered an embarrassment and effectively suppressed. However, after the boxing thriller Killer’s Kiss, and the clever, twisty noir The Killing, Kubrick broke into Hollywood with the social-issue first world war picture Paths of Glory. After a difficult experience on the big-budget epic Spartacus, Kubrick left Hollywood to make the UK his base, completing a string of increasingly ambitious, highly impactful films: in the 60s he made Lolita, Dr Strangelove and 2001: A Space Odyssey; the 70s spawned A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon; in the 80s he released The Shining and Full Metal Jacket. However, his output began to slow, and his only film of the 90s – and his last – was Eyes Wide Shut.

Kubrick’s reputation as a director was fully secure in his lifetime (though he only won a single Oscar, for best special visual effects for 2001), and in his latter years, he did his best to avoid the media, with much of the press suggesting he was a recluse. However, in the years since his death, evidence has emerged that throws considerable light on his working methods, as well as allowing more human aspects of him to emerge. Much of the exhibition is drawn from the archives that Kubrick himself kept at Childwickbury Manor near St Albans, which he bought in 1978 and lived in with his family.

These archives were first opened for inspection after his death, with the Guardian’s Jon Ronson being one of the first journalists allowed to rifle through the piles and piles of material. Much of the material has since been transferred to a storage facility at University of the Arts London’s Elephant and Castle campus. Kubrick’s brother-in-law Jan Harlan made a reverential profile, A Life in Pictures; a view-from-the-bottom has come via another more recent documentary, Filmworker, featuring Leon Vitali, one of Kubrick’s legion of assistants. Kubrick’s stepdaughter Katharina, who lived at Childwickbury with her mother, Kubrick’s third wife, Christiane, says that while “Dad never threw anything away” it is unfair to call him an oddball: “He was passionate, and he loved his job … He was no more obsessive than anyone else who lives by working on something they love to do and want to get it right.” She says the reaction after his death in 1999 was “awful for the family” as the news media “was full of nonsense, regurgitating old stories that weren’t true anyway”.

In fact, she says, Kubrick simply “had his life so sorted”. “He had a house he could do everything in; he could sleep in his own bed at night; the people he wanted to see came to him; he wasn’t known for his face so he could go to Marks & Spencer’s if he wanted.” Family was important: she says Kubrick sent his trophies to his mother, and the family dinner table (naturally, the one from The Shining) was the venue for many discussions about upcoming projects – “our jaws dropped when he told us he’d asked Steven [Spielberg] to direct AI”. She also says Christiane was not unhappy when he abandoned his Holocaust film Aryan Papers in the mid-90s, after Spielberg released Schindler’s List, as working on it made him “profoundly depressed”.

Part of the reason behind Kubrick’s longevity as an artist is the willingness with which others have championed his work. Christopher Nolan became a high-profile flagwaver for 2001: A Space Odyssey with the production of his own existential space epic, Interstellar, released in 2014, and led the presentation of a restored version of 2001 at the Cannes film festival on its 50th anniversary. A renewed surge of interest in The Shining was triggered by the documentary Room 237, released in 2012, which elaborated numerous theories about the film’s meanings. A Clockwork Orange became a significant totem during the Britpop era in the mid-90s, with Damon Albarn imitating Alex DeLarge in a music video (directed by Jonathan Glazer) for The Universal. Spielberg embarked on the ultimate act of fan worship by releasing AI: Artificial Intelligence in 2001, two years after Kubrick’s death.

Such is the dazzling variety and accomplishment of Kubrick’s work, it remains hard to get a handle on him as an artist. Confessing he has become a Kubrick “nerd”, Sudjic says: “Very few film-makers in the 20th century have had the range and the credibility of Stanley Kubrick. Each film was entirely different, each film was an imagined world, every aspect of which came from Kubrick’s creative control. That’s extraordinary, that’s very special.”

Born 26 July 1928

Died 7 March 1999

Career: Staff photographer for Look magazine in the late 1940s before turning to film-making. Completed a series of low-budget independent films including The Killing, before breaking into Hollywood in 1957 with the Kirk Douglas war picture Paths of Glory. After becoming disillusioned with Hollywood in the wake of Spartacus, he shifted his base to the UK, creating a string of technically innovative, critically acclaimed masterpieces, including 2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange and The Shining. He died six days after handing over an edit of his final film, Eyes Wide Shut.

What he said: “Anyone who has ever been privileged to direct a film also knows that, although it can be like trying to write War and Peace in a bumper car in an amusement park, when you finally get it right, there are not many joys in life that can equal the feeling.”

What they say: “In a dozen or so films Kubrick demonstrates his remarkably adventurous versatility, endlessly inspiring us to realise you can be widely varied in form and content, without ever losing your vision and style.” – Mike Leigh