There’s a line in Jim Jarmusch’s 1986 film Down By Law that seems apposite in November 2016. It goes: “My mama used to say that America’s the big melting pot. You bring it to a boil and all the scum rises to the top.”

Over tea in a Paris hotel, Jarmusch considers whether he’d agree. “Kind of appropriate, but also kind of cynical,” he says finally. “But it’s a scary and sad time with these creeps coming to the top. I think we all have to be vigilant around the world now with Brexit, and Marine Le Pen in France. There’s a lot of scary shit, you know?”

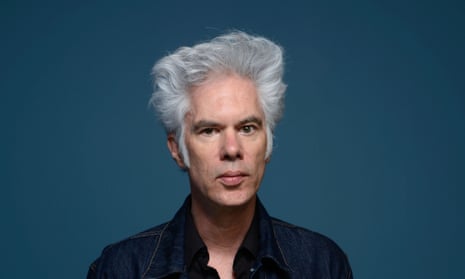

Jarmusch is 63 but looks exactly as he has for the last 30 years. He’s wearing dark glasses indoors and is dressed as if he may at any moment be called on to play guitar with the Velvet Underground. His hair is that crown of pure white that makes him look like David Lynch’s beatnik brother. It turned that way when he was 15 due to an inherited condition. Tom Waits once said it must have made him an “immigrant in the teenage world”, casting Jarmusch as a lifelong outsider.

He made his first film, 1980’s Permanent Vacation, with a grant he was supposed to use to pay his tuition fees. Ever since, his meditative stories about society’s waifs and strays have blurred the line between mainstream movies and arthouse cinema. Films such as 1995’s “psychedelic western” Dead Man and 1999’s Ghost Dog, about a mafia hitman who follows the code of the samurai, established him as a singular voice in US film with a taste for subverting genre. He remains fiercely independent and has never made a film for a major studio. The only thing that’s changed over the years are his vices. The director of Coffee And Cigarettes no longer touches either. He quit coffee in 1986, and cigarettes followed a few years ago.

“I have caffeine in tea – and sugar, that’s a vice,” he says. “I drink only dry white wine and very dry champagne, but not daily. I don’t drink hard alcohol and I don’t drink any other stuff. I love weed, but I don’t smoke now. Maybe I will again. I’m just trying to be, you know, clear.”

That clarity of thought comes through in his latest film, Paterson. In a loud and angry world, it is a soft and still voice. It follows a week in the life of a bus driver named Paterson, played by Adam Driver. He lives and works in the town of Paterson, New Jersey with wife Laura, an aspiring country singer played with manic pixie energy by Golshifteh Farahani. Paterson writes poems, although he has no desire to publish them. Laura bakes and sells cupcakes. They encourage one another and never fight. If this all sounds a little underwhelming, that’s sort of the point. It’s a celebration of the everyday.

Driver tells me he’s such a fan of Jarmusch’s work he would have been “on board for whatever it was he wanted to do” but that he fell for Paterson because it’s “the antidote to movies that are full of action, chaos and crisis. The biggest action is the bus breaking down, and how funny it is that that’s the thing that sends people into a crisis. They’re all talking about it exploding into a fireball, which is kind of hilarious.”

There have been so many high-stakes blockbusters where the destruction of the Earth is threatened that it’s become banal, but Jarmusch says he wasn’t consciously responding to that. “This is just a quiet story,” he says. “Life isn’t dramatic, always. This is about the day-to-day. It was less intentionally an antidote to all this action, violence, abuse of women, conflict between people, but I’m sure that’s part of it. We need other kinds of films. With my films, my hope is that you don’t care too much about the plot. I’m trying to find a Zen way where you are just there each moment and you’re not thinking too much about what’s going to happen next.”

Jarmusch has alluded to poets such as Walt Whitman and Robert Frost in his films before, but here he places the act of writing at the heart of the story. It’s not easy to do that without smacking of pretension, yet Paterson’s poems – in fact written by the New York School poet Ron Padgett – all seem to rise naturally from the routine of the bus driver’s life. Jarmusch, who studied poetry under Kenneth Koch and David Shapiro at Columbia University, may have turned to film-making early on, but he still delights in incorporating other media into his work. “What I love about film is it has all the other forms inside of it. It has composition, music, time, language, everything,” he says. “It’s the closest thing humans make to dreaming.”

He calls the New York School poets his “aesthetic godfathers” and is full of praise for Frank O’Hara’s Personism manifesto. “They said: ‘Make a poem to one other person, don’t make a poem to the world. Don’t take yourself too seriously. Allow humour,’” he explains. “Their poems are very funny and have so much exuberance. Why shouldn’t poetry be that way?”

A perfect example of such a poem is William Carlos Williams’s This Is Just To Say, read aloud in the film and undoubtedly the loveliest lines ever written about nicking your wife’s plums. Williams was a Paterson native, and Jarmusch first conceived the film when he visited the town in the early 90s on a pilgrimage to understand the poet’s home. Much as Down By Law was a prison-break movie where you didn’t see its leads break out of prison, Paterson is a love film where you don’t see its leads fall in love. Jarmusch has been with his own partner, the film-maker Sara Driver, since they worked together on his first movies almost 40 years ago, and says he wanted to make a film about the mutual understanding needed to make a relationship last.

“If you love somebody, if it works, it’s because, most often, in my opinion and observation, you let that person be who they are,” he says. “You don’t try to change them. Of course, you have to make compromises in any kind of relationship, whether it’s a love one or a working one, but as soon as you start telling the other person why you want them to be some other way that’s the beginning of the end. That’s conflict. How does that feel to the other person? That they’re inadequate.”

In the film, the couple live independent lives. Paterson goes out every night to the same bar, and at the weekend when Laura goes off to sell her cupcakes Paterson doesn’t go with her. “For me, it’s incredibly important to have space,” says Jarmusch. “I need time always in my life to be alone. It’s when I work things out and get ideas. They allow each other that.”

Paterson is an adult movie, in the sense that it’s about grownup love and work and routine – but it’s not X-rated. Quite the opposite: Paterson and Laura are affectionate but chaste onscreen. Some critics have argued that the idyll of the film would be broken by the friction of sex but Jarmusch doesn’t see it that way.

“They’re very tender,” he says. “I just didn’t need to show them fucking. I shy away from it in films because I find it very cliched. Sex is very varied. Sex can be funny, tender, a little rough, wild, soft, frustrating, incredibly satisfying… so when you isolate a sex scene between two people, are you going to define their sexuality in that one way? It makes me a little nervous as a storyteller.”

If he ever makes a film about sex it would have to represent that totality. “I have an idea for a script that I’ve been carrying around for a long time,” he says. “It’s about two young lovers, and if I make this film they will have sex a lot so that I can show the variations and permutations.”

It’s not hard to imagine why he hasn’t got round to the project yet. Paterson is the second Jarmusch film to be released this month. The other is Gimme Danger, a documentary about another American poet, Iggy Pop. It tells the story of the formation, self-destruction and eventual redemption of the Stooges. In it, Iggy describes his desire to write short, reductive lyrics and to never, ever write like Bob Dylan. Jarmusch believes he’s being self-effacing. “If you listen to China Girl, I bet Bob Dylan would love to have written that,” he says. “[Iggy]’s an unrefined intellectual, but totally intellectual. It’s like Mark Twain said: ‘Don’t let school get in the way of your education.’”

Iggy has appeared in two previous Jarmusch films, Dead Man and Coffee And Cigarettes, and has always seemed at home among his cast of drifters, hustlers and down-and-outs. Compared to the nervous energy of those films, Paterson is a departure, being about a couple who’ve found a measure of contentment.

“Often my characters are outsiders who are against conforming to the world,” says Jarmusch. “In Paterson they are within the world and yet they find their own outlets to be creative. For the last 10 or 20 years I’ve been studying tai chi and qigong, and I’ve learned that when I was young I wanted to stop the thing.” He strikes his fist with his palm: “That’s hard, and harsh. In martial arts you realise that you can let that energy carry it away from you. You don’t go against it. You move it, and control it if you can. Maybe the secret of the universe is to go with the grain.”

Paterson is in cinemas now

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion