From across the park, a low-pitched, adolescent chant starts up: “Jess-EE! Jesse-Eisen-BERG!”

“Ooh, no,” Jesse Eisenberg says, dipping his head. The 32-year-old actor, a New Yorker most of his life, is living in London at the moment while he appears in a West End show. On a thickly warm afternoon, we wander into a park in east London that seems ideally deserted until a local school clears out for the day, sending a dozen teenagers our way. Quickly they recognise Eisenberg, from the spring blockbuster Batman v Superman, in which he played the villain Lex Luthor, as well as 2010’s The Social Network, in which he put in an Oscar-nominated performance as Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg. They heckle with glee: “Jess-EE! Face-BOOK! Super-MAN!”

Eisenberg quickens his pace along a path heading towards a wooded area. “Maybe if we just keep walking?” he wonders. “Maybe if I don’t respond to my own name?” But the chanting gets louder and, glancing back, we see the kids have begun to follow. “Ooh, no.”

Eisenberg is also a writer. He has a book of short stories to his name, many of them first published in the New Yorker, and he has written and starred in a trio of plays, the latest of which, The Spoils, has brought him to London. Without wanting to malign either profession, Eisenberg is perhaps more obviously a writer, in terms of his manner and appearance, than an actor. He speaks rapidly, mutteringly, in great long paragraphs full of observation and introspection and drollery and doubt, generally frowning at the floor while he does so. He’s bony, hunched, handsome in an undernourished-looking way – inconsistently shaved, today, and wearing a faded T-shirt that he keeps skittishly tucking into his jeans, then tugging loose again.

Tuck. Untuck. I recognise the gesture, I tell Eisenberg, as we walk. He was doing it on stage last night in The Spoils, portraying the twitchy protagonist Ben, a wealthy, idle Manhattanite who slowly alienates his friends by being socially ungovernable. “Oh-oh-oh this?” Eisenberg says, tucking in the T-shirt again, then untucking it. “Oh! The shirt’s too long, maybe, I don’t know.”

As an actor, he has a Dustin Hoffman-like repertoire of tics (lip flutters, fingertip taps, muttered half-laughs) that he uses to hint at his characters’ internal disorder. At a screening of Eisenberg’s new film, Now You See Me 2, a sequel to the 2013 action-comedy about a gang of adventuring magicians, I spotted a new addition to the repertoire. Eisenberg, playing the gang’s token neurotic, kept convulsively squeezing his sides with his hands, like someone operating a bicycle pump. I’m surprised, I tell him, to see these gestures carry over into real life.

“I guess we all do… things,” Eisenberg says, lamely. Unsatisfied with this answer, he continues: “I’m in the spirit of The Spoils, I guess. I have one foot inside my character. This is an unusual day for me.” He means being outdoors, scurrying along a tree-lined path trying to evade a pack of junior stalkers. Curtain up on tonight’s performance is a few hours away. “So normally I’d be sitting at home right now,” he says. “Kind of doing nothing, but thinking about the show.”

Is that healthy? “It’s not. We’re only doing a short run of The Spoils for that reason. Because I find doing plays totally consuming, in ways that don’t feel sustainable. I worry about the show from the moment I wake up. The only calm I have in my day is after it’s over.”

When I ask how long that calm tends to last, Eisenberg calculates for a moment and says: “Maybe 10 minutes?”

Before we meet, I expect to feel a degree of affinity with Eisenberg. We’re both Jews, inveterate mumblers, the same age and, despite a difference in height, similar in appearance. (The first thing Eisenberg says, when we shake hands, is, “You’re like me. But stretched.”) As it turns out, it takes a half-hour of disorienting conversation before I can get any sort of handle on his strange rhythms of speech, his spiralling patterns of thought.

He has a tendency to subject his words to instant examination, sometimes offering an overlaying commentary on statements just made. On worrying about his play: “I probably do this, unconsciously, in an attempt to create meaning in a show I’ve already done 100 times.” And on worrying about things such as this: “I don’t think I gain much from being able to describe my own unconscious needs manifesting consciously – that’s probably not necessary. I don’t think humans were doing that when they were hunting.” He calls all this “articulating my meta-experience”.

It isn’t always clear when Eisenberg is teasing and when he’s not. If his mannerisms are evocative of Hoffman, his chat is more Woody Allen, a wry, tireless patter, the world a quarter amusing and three-quarters appalling. His jokes rely as much on tone and context as content, and as such are easily missed. When the warmth of the summer afternoon suddenly breaks, for instance, and an absurdly heavy rainstorm soaks him through, Eisenberg gasps: “What’s going to happen to us?” When we make for the nearest tree, sheltering under it, the actor looks at me and says, “If this was a movie, we would kiss.” When the teenagers who have been patiently trailing us take cover under a tree of their own, he eyes them and mutters: “I feel like we’re going to be accosted. I feel like we’re going to be attacked.”

I ask what he was like, at their age. He frowns. “The best moment of my childhood was when my friend told me I was ‘as funny as Steve Urkel’. [Urkel was a character in the US sitcom Family Matters.] I’m serious. Because until then I never thought of myself as funny. I thought of my older sister as funny. It was, like, the first time anybody validated that for me.”

His father is a sociology professor, his mother teaches dance, and used to take bookings as a professional clown. Jesse, with older sister Kerri and younger sister Hallie Kate, grew up artsy, first in New York and then in New Jersey. Kerri acted from a young age in Broadway theatre, and Jesse did, too. For a while, he was an understudy in A Christmas Carol and later had a small part in a Tennessee Williams play. “And I was not good in any of it. I was just there because my sister was doing it, and I wanted to be with her.”

He wasn’t doing so well in mainstream education at the time. Eisenberg never fitted in at junior school, he once told an interviewer at the New Yorker, and for a period refused to go. He later told GQ magazine that, as a seven-year-old boy, he “cried every day” in class. Things got better when he transferred to a school in Manhattan that specialised in the performing arts. “Acting school was a safe environment,” he says now.

Though he does not name any condition more specific than “anxiety” in conversation with me, Eisenberg has in the past spoken about his treatment for obsessive compulsive disorder. (“I’m on a strong regimen of pills,” he said in 2009.) His better short stories play around with characters in therapy, or in therapy-like situations. In one story, an uncle is pushed to greater self-understanding by a young nephew who asks one question: “Why?” In another, a patient visits a therapist who talks only in sports cliches. Eisenberg once suggested that he gravitated towards playing anxious characters because he couldn’t be sure he’d come over any other way on set. “I need to stay busy,” he tells me. “Otherwise I go a little nutty.”

Happily, he has been in work since he was 16 and cast in TV sitcom Get Real. At 18, he sold his first screenplay to a Hollywood studio. (The movie, “a shallow but well-crafted commercial comedy”, as Eisenberg describes it, was never made.) That year, 2002, he appeared in an indie film called Roger Dodger, in which he impressed as a naive, virginal youth who was tutored in the ways of picking up women by an older lothario. In 2005, when Eisenberg was in his early 20s, he came to wider attention as the excruciatingly precocious Walt, teenage son of divorcing parents in Noah Baumbach’s muted comedy-drama The Squid And The Whale. Both these characters, force-marched into maturity by the reckless adults in their lives, were pitiable, but Eisenberg made room to explore their callowness and unpleasantness, too.

When was the first time he thinks he got it right, I ask – really nailed it as an actor? “Uh. Uh. Uh.” Eisenberg stamps his feet, considering carefully. “Well, I did this movie once, called Holy Rollers. It was about a Hassidic Jewish kid who becomes a drug dealer…”

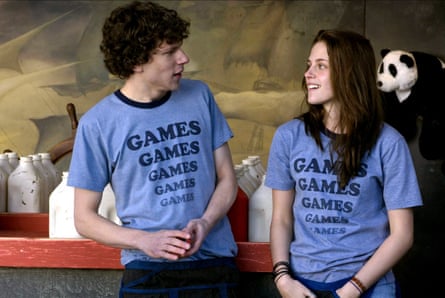

Holy Rollers was released in 2010, so Eisenberg has briskly written off about a decade of screen work: not only Roger Dodger and The Squid And The Whale, but Adventureland (2009), a strange and brilliant indie in which he played a young amusement park employee. Eisenberg explains: “Holy Rollers was the first time I felt like I was acting for myself. Not the people that hired me.” He isn’t sure he did anything really special as an actor again (“working at my creative best”) until he was in Richard Ayoade’s drama The Double, in 2013, cast in a double role as identical-seeming office workers, Simon and James, who chase the same woman, played by Mia Wasikowska.

What about The Social Network? His performance as Zuckerberg was so persuasive, I thought, that it’s now hard to think of the reclusive Facebook founder without elements of Eisenberg’s fictional portrait coming to mind: the constant, robotic misunderstandings with friends and colleagues; the moment when his glassy-eyed belligerence finally gives way to fear as he’s violently confronted by a co-founder. I agree with the New Yorker’s critical take: “an indelible performance”; but not so special to Eisenberg?

“The Social Network was just a bigger movie,” he says, “with more specific expectations. And so, as an actor, you’re more conscious of those expectations, and it necessarily feels less personal. Even if it’s of a high quality, which of course that was, you just feel like it’s impossible to have that real connection.”

When he was cast as the sinister technologist Lex Luthor in the new Superman movie, an announcement made back in 2014, fans might have had his stellar work as a sinister technologist in The Social Network in mind. They responded warmly to the appointment. Expectations ran high for months, but when Batman v Superman was released this March, it proved a distressing mess: overlong, charmless, with Eisenberg’s role not much more glorifying than anyone else’s. Something had gone wrong in his performance, I thought. Where his Zuckerberg was brilliantly shifty, his Luthor seemed only smarmy, annoying instead of dramatically aggravating. Though Batman v Superman wound up making a lot of money, critics absolutely hated it.

Eisenberg tells me he didn’t read the reviews or the surrounding commentary. But he must have been vaguely aware of the kicking the film took?

“Uh, that film, I succeeded and failed in that film years before it came out.” Eisenberg means during production, when he was shooting his scenes. “At the end of the day, if I felt like I accomplished what I wanted to accomplish with that character, then it’s a success.” One of his co-stars, Jeremy Irons, recently acknowledged Batman v Superman wasn’t up to much. Whether from a greater sense of diplomacy, or an acknowledged tendency to be self-absorbed, Eisenberg takes a more personalised view. “Why would I worry,” he wonders, “about the specific gripes people have with something I do that is for myself?” He says that the only critic he cares to listen to is himself. “What other person looks to a consensus for how to do their job?”

I say a lot of people do. “Well, that’s unfortunate.”

Eisenberg agrees there’s a measure of self-protection in his way of thinking. Some years ago, he was in an independent movie called The Living Wake. It had a perfect script; filming was thrilling and satisfying; then he saw himself in the trailer and thought, “Oh, shit, I’ve ruined it.” Eisenberg didn’t watch the final version on its release in 2007 and hasn’t watched any finished movie he’s been in since. “I realised I didn’t have to. That it was a totally unnecessary part of the experience.”

Is he really not curious? “The curiosity,” Eisenberg says, “is outweighed by my terror.”

Still trapped under the tree, with the rain not letting up yet, we discuss other matters. Brexit (he’s intrigued, particularly by the immigration debate, the flavour of which he recognises from home). American basketball (he’s devoted). At one point, he idly wonders why the kids who have been following us all afternoon are “wearing little suits” – in New York that would usually indicate they go to a private school, which they don’t – and then he describes how his parents drilled into him and his siblings the outsize importance of social causes. “It was totally understood, growing up, that we should support people who are struggling. This was not debatable – in my family, no one talked about, you know, the value of lower taxes. We talked about the value of education, of social security, of universal healthcare.”

Was it a strange choice, in that case, to pursue a career in entertainment, rather than something more tangibly useful? Eisenberg points out that, just before coming to the West End, he spent four months volunteering at a domestic violence shelter in Bloomington, Indiana. While there, he collaborated on a fundraising campaign with the University of Indiana and raised $500,000, enough to pay off the shelter’s mortgage. “I would say this is a very clear example of using entertainment, or at least using a by-product of entertainment, in this case public notoriety, for something that’s more directly related to social justice.”

Why that particular shelter? Why Bloomington? “I was there for, like, personal reasons. For reasons I don’t want to bring up in an interview.”

This statement, of course, proves too enigmatic to ignore, so afterwards I do a bit of investigative Googling. When the Indiana Daily Student wrote about Eisenberg’s work at the shelter in April, it described charity worker Anna Strout, whose mother is executive director of the shelter, as Eisenberg’s girlfriend. The two were a couple in their 20s; in 2011, Eisenberg told an American magazine that Strout was the only woman he’d ever been on a date with. In 2013, they appeared to have separated, and Eisenberg was pictured on dates with his The Double co-star, Mia Wasikowska. For a couple of years, the two were photographed every so often in cafes and airports, but neither actor ever confirmed or denied the relationship.

I ask what it was like, as a socially uneasy individual at the best of times, to be subjected to paparazzi attention during that period. Eisenberg grimaces, shrugs. He compares it to the fact his dad teaches at a college campus that’s five hours from the family home. “Jarring, but it means he gets to do this thing he loves. The moment I complain about the totally disproportionate relationship between the wonderful perks I get [as a public figure] and the minor inconveniences that I’m tasked with encountering, is the moment I hope somebody slaps me in the face.”

Take being interviewed, Eisenberg says. “The whole context of what we’re doing right now is vain for me. But all of our lives have unusual circumstances. And you learn to live with those circumstances.”

Without warning, he twists his head in my direction and tumbles out a long, messy question of his own. “When I’m talking to you, and I can sometimes see your reactions, and I’m trying to gauge your reactions, do you look at me and think, ‘God! What an indulgent prick’? Or do you look at me and think, ‘This guy is smart and he thinks about what he does’? I ask because I wonder how I sound. Because nobody ever tells me to shut up.”

I say I think it must be tiring, being him.

He sniffs a laugh. “I know my circumstances are the luckiest circumstances that have existed since, y’know, the dawn of civilisation. I recognise that in an intellectual way. I just still put a lot of pressure on myself. When I think about the kind of luck I have, of not only being born in America, but being able to do the things that I want to do, it feels pretty stupid to feel anxiety.” He tugs at his T-shirt.

The heavy rain has started to ease. The schoolkids, inching closer, dashing from tree to tree, now step into the drizzle for a bolder approach. “So the kids are coming,” Eisenberg says. He reminds himself, at the last minute, to be nice (“I should be nice”). Then he turns to face them. The scene that follows is a little strange at first and, in the end, rather lovely.

“Oh, hi, hi, hi,” he says, bombarding the arriving group with questions before they can say anything. “You made it over here? You literally followed me? Don’t you have things to do? What are your lives like? Do you want to come underneath here? You go to school here? Were you walking home? Where does everybody live? Around here? Do you like it?”

For a moment, the kids are silent, dumbstruck. What are our lives like? Then, all at once, they respond with giant smiles and cries of, “Oh my days!” and they surround Eisenberg to shout brassy questions of their own. For 10 minutes, under dripping shrubbery, the kids and the movie star interrogate each other. What are you doing in London not Hollywood? (“I don’t know!”) Why are you all wearing funny little suits? (“We don’t know!”) Can you really get out of handcuffs like the magician in Now You See Me? (“Yes! Don’t try it.”) Who’s the best at drama? (“Me! Me! Me!”) They discuss Brecht, whom the kids have been studying. They discuss Hitler, same. One of the boys, hovering near the back with a basketball in hand, says to Eisenberg, “Sorry for following you around. Sorry if we made you feel weird.”

He replies, simply: “I always feel weird. This is no different.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion