A 300-year-old story by Madame d’Aulnoy, the 17th-century French writer who coined the term “fairytales”, is to be published in a modern English translation, telling of a woman whose beauty is so great it slays her lovers by the hundreds.

Marie-Catherine Le Jumel de Barneville, known as Madame or Countess d’Aulnoy, invented the term “conte de fée” or fairytale, when she published her major collection of them in 1697-98.

Unlike the work of her French contemporary Charles Perrault, or later authors such as Hans Christian Andersen and the Brothers Grimm, today her collected work rarely appears in new English-language editions, but rather in mixed anthologies – a contrast to the editions published up to the early 20th century in England and the US.

Now, in the wake of a 2019 two-volume collection of D’Aulnoy’s fairytales from the independent US publisher Black Coat Press, Princeton University Press is releasing a collection of her work in April.

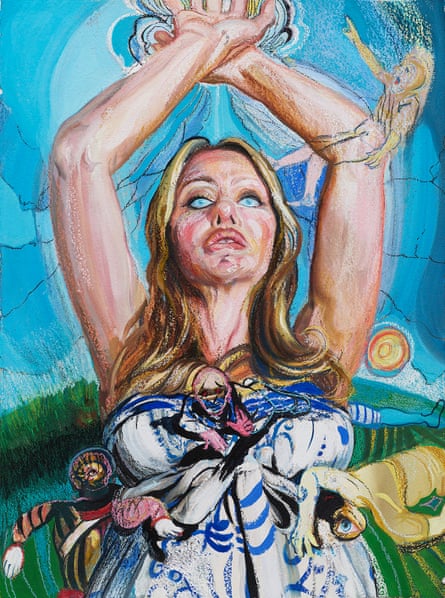

Entitled The Island of Happiness, it features illustrations and an essay by the artist Natalie Frank. It also contains a new English translation of The Tale of Mira, one of D’Aulnoy’s earlier stories, which sees the beautiful Mira kill scores of men: “anyone who saw her fell desperately in love with her. However, her pride and indifference made all of her lovers die”, until she falls for a man who is indifferent to her.

Frank called it a “feminist ghost story for the ages” which is “laced with dark comicality”.

“A traditional fairytale warns of the dangers of unrequited love; this one warns of the violence that occurs out of unreciprocated lust, poking fun at the seriousness of a tragic fairytale story,” she writes in her introduction.

The Tale of Mira is drawn not from D’Aulnoy’s fairytales of the late 1690s but from an earlier fictionalised travelogue, The Lady’s Travels into Spain. Published in France in 1690-91, the book soon appeared in a succession of English editions, reflecting D’Aulnoy’s popularity in England in the first half of the 18th century.

Other stories in the Princeton collection include Finette Cendron, in which a king and queen lose their kingdom because of their decadence, and abandon their children in the forest; and Belle-Belle, in which a cross-dressing countess helps a king who has lost his kingdom.

“Ask anyone familiar with fairytales or any scholar about the best classical fairytales, they will generally only name men – Charles Perrault, the Brothers Grimm, and Hans Christian Andersen,” said the academic Jack Zipes, who introduces and translates the collection. “Nobody would ever mention the mysterious Marie-Catherine Le Jumel de Barneville, who was actually the most intriguing pioneer of the literary fairytale in the 17th century and is still relevant today.”

D’Aulnoy was born in 1650. She was married at the age of 13 to a notorious gambler 30 years older than her. She tried to have him killed without success, spent a brief period in prison and then travelled around Spain and England for more than a decade, a period during which she is believed to have worked as a French spy. In 1690, she returned to Paris, where she opened a salon and became France’s foremost fairytale author before her death in 1705, said Zipes, describing her as “more notable” than Perrault.

“Powerless, D’Aulnoy and many other gifted women authors of fairytales … discovered their power through the salons and through conceiving fairytales that announced and pronounced their social views of civility,” said Zipes. “The aristocratic writers often used the term fée among themselves, and created an atmosphere in the salons in which they could freely exchange ideas that challenged the hypocrisy and immorality of Louis XIV’s court.”

D’Aulnoy’s tales, he said, “placed women in greater control of their destinies than in fairytales by men. It is obvious that the narrative strategies of her tales, like those she told or learned in the salon, were meant to expose decadent practices and behaviour among the people of her class, particularly those who degraded independent women.

“What interested her most of all was the status of women, the power of love, ethical behaviour, and the tender relations between lovers. Without love and the cultivation of love, she believed the ideal and just society could not exist.”

Gloria Steinem praised the forthcoming collection and Frank’s interpretation of the stories, saying that “in giving us back the women heroines and images and lives that were once the heart and soul of the oldest stories, Natalie Frank is giving back to female readers the right to honour and tell our own stories”.