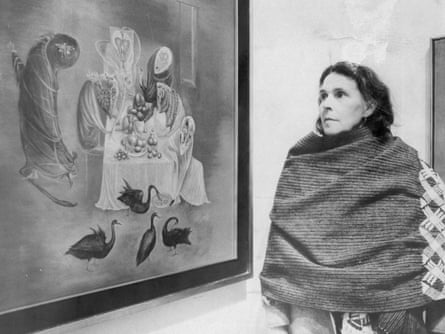

When Joanna Moorhead told Leonora Carrington that her surreal, Bosch-inspired painting The Giantess had been sold at Christie’s in New York for $1.5m, the artist thought she must be joking. Moorhead got an identical reaction when, in the same year – 2009 – she called to say that Carrington’s carnivalesque feminist story The Hearing Trumpet had appeared in a list of novels everyone should read. For decades, Carrington was largely unknown in the US and her native Britain, until recognition began to build in the mid-1980s. Even then, it is only over the last decade or so, before and after her death in 2011, that interest in her work has quickened sharply. Now, in this centenary year of her birth, her international fame is finally secure, though her pictures and stories remain as surprising as ever.

They will always have to compete for attention with her remarkable life: the flight to Paris, aged 20, to continue her affair with the older, married surrealist Max Ernst; the involvement with what Moorhead calls “the most exciting group, artistically speaking, on the planet” – Picasso, who lived down the road, would pop by and dance around, bottle in hand; her rescue, having been subjected to horrifying treatment in a Spanish asylum, by her old nanny, who arrived in a submarine; her outrageous art pranks that included slathering her feet with mustard in a fancy restaurant, and confounding Luis Buñuel by taking a shower fully clothed. There are many more such tales.

Carrington was long known within the art world for being spiky and uncompromising – unwilling to play the game of self-promotion or to provide insights into her work. On first talking to the artist at her dark, chilly home in Mexico City, Moorhead naturally got out her notebook. “What’s that?” Carrington asked fiercely, and reminded the journalist that she was there principally as a member of the family. Indeed, The Surreal Life of Leonora Carrington is not simply a biography, but also a spirited account of the author’s friendship with her father’s famous cousin, who had long refused to return to Britain. Moorhead seems to have discovered only in 2006 that the woman barely mentioned at home but known to her parents as “Prim”, and written off as “a neglectful daughter, a selfish sister, an absent aunt”, was an artist of renown. She set off to meet her family’s black sheep, then aged 89 but still rebellious, and was immediately “dazzled”. Over the next five years, her lengthy trips to Mexico allowed a grateful Moorhead to “taste another life”.

Carrington was a former debutante art student when she was introduced to Ernst in London in 1937; surrealism was all the rage and the German artist one of its most prominent practitioners. He was also a womaniser, and their relationship angered Carrington’s tycoon father to such a degree he took steps to have Ernst arrested for exhibiting work that was pornographic. The lovers fled to Cornwall, where a hedonistic house party, involving Paul Eluard, Eileen Agar and Man Ray, was captured in the photos of Lee Miller. Included in Moorhead’s book is the shot of Ernst with his arms across Carrington, “his fingers fanned out across each of her breasts, his strong, veined hands old and lined against the alabaster sleek of Leonora’s smooth, young chest”.

The escape to Paris came soon after; Ernst had made the journey in advance, to placate his inconvenient wife. “I always did my running away alone,” Carrington later told interviewers. It’s difficult to be precise about some of the details of the next years. As her biographer points out, for all their avant garde ambitions, the torchbearers of surrealism were not “forward-looking when it came to women and their place in the world”. Carrington told Moorhead that when Joan Miró once gave her some money to get him some cigarettes, she gave it back and “said that if he wanted cigarettes he could bloody well get them himself. I wasn’t daunted.” Yet to an earlier interviewer Carrington told the story differently – she had got the cigarettes, though begrudgingly. Memories are unreliable and wishful thinking common. More important is the demonstrable fact that she wasn’t content merely to be a muse, or a submissive femme enfant. In Paris, she was already painting, notably Self-Portrait, which features a Carrington figure with wild black hair and a white horse galloping away to freedom. She also became a published writer with “The House of Fear”, a story typical in its fabulism and dryness of tone (Marina Warner’s apt phrase is “deadpan perversity”).

Many of Carrington’s stories are themselves a subversive retort to the male surrealists’ view of women; they have a “fuck you” quality to them, which sits nicely alongside their sheer dreamlike weirdness. “Leonora told me that every piece of writing she ever did was autobiographical,” Moorhead recalls, and her book confidently interprets the meaning of such stories as “The Oval Lady” and “Waiting”, which appear with two dozen others in a beautiful new volume, The Debutante and Other Stories, published by Silver Press. Angela Carter, a fellow fabulist, included the title story in her Virago anthology Wayward Girls and Wicked Women (1986); in it, a deb sends a hyena in her place to a high-society ball: the stinking animal wears high-heeled shoes, gloves to hide its hairy hands and the torn-off face of her maid “nibbled very neatly all around”.

Carrington and Ernst enjoyed a mostly happy and productive spell in the Ardèche until, on the outbreak of war in 1939, Ernst was imprisoned as a German citizen. Carrington eventually travelled to Spain, “consumed”, Moorhead writes, “by grief and guilt at leaving him”. Down Below, her harrowing narrative of mental breakdown and treatment – she was strapped to a bed and given a drug that induced epileptic fits – has just been reissued by New York Review Books. Moorhead compares it to Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, and says that Carrington wouldn’t, or couldn’t, talk about the episode. So, as part of her biographical quest, Moorhead visited the site of the hospital in the port city of Santander, and “felt her spirit was very close as I wandered across the park”.

Her book deals engagingly with Carrington’s short-lived reunion with a still-smitten Ernst in Lisbon and New York, her two marriages, and in particular her friendship in Mexico City with Remedios Varo, the painter and wife of the surrealist poet Benjamin Péret. As a teenaged visitor to Italy, Carrington was very taken with the art of Uccello and Arcimboldo; in the Prado in Madrid she became fascinated by Bosch and Bruegel. In Mexico, these influences on her pictures were overlaid by a growing interest in spirits and the occult, which she shared with Varo. Living in a country that Andre Breton anyway called the most surreal nation on earth, she delved into astrological and Mayan imagery, tarot, Kabbalah and Buddhism. Her canvases were filled with strange furred and feathered hybrids and horned beings. As Ali Smith has written, the dark and colourful paintings are full of “many-armed lizard-snakes, creatures half-human-half-wolf, people turning into birds”. Masked gnomic animals “stand waiting in a space that’s part recognisable and part fantasy, somewhere liminal between benign and malign”.

Carrington’s marriage to Csizi Weisz was stable, though she has said in interviews that her explosive sexuality plagued her for decades; there were affairs, including with the Mexican poet Octavio Paz. She attended the second wedding of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera – Kahlo called her and her associates “those European bitches”. Carrington, Varo and their photographer friend Kati Horna were very close in the 1950s; their children grew up together (Carrington worked, she has said, with a baby in one hand and a paintbrush in the other). As Moorhead writes, “in a hidden corner of Mexico City, Leonora, Remedios and Kati took Surrealism to a new place, a place where it was women-centred and instinctive”.

Carrington left Mexico in 1968: she had attended some political protest meetings and was told she was in danger from the government. For the next 25 years she based herself in the US, pursuing her independence once again. Eventually she returned to the house in Mexico City at the door of which Moorhead, her soon-to-be ardent admirer and friend, nervously presented herself in 2006, to take on the task of telling “Leonora’s story … in the way I believe she wanted it to be told”. “I felt at home” in Mexico, the artist once said – though “as one does in a familiar swimming pool that has sharks in it”.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion