Sitting in prison cell number 252 in Mons city jail, Paul Verlaine, the then little-known French poet, drew sketches and composed what many literary critics consider to be his finest poetry.

Unlike his contemporary and friend Oscar Wilde, who was sentenced to hard labour in Reading jail, the Frenchman – who had been convicted of shooting his fellow poet and lover, Arthur Rimbaud – had a relatively easy incarceration. Away from the Parisian cafes, the beer and, particularly, the absinthe that was to destroy his health, Verlaine converted to Roman Catholicism and spent his 555 days behind bars reading, and writing work that would later earn him the title of “prince of poets” among his peers.

Now Mons is staging what is claimed to be the biggest ever exhibition on Verlaine, including many privately owned manuscripts, photographs, letters and documents that are rarely, if ever, on public display.

Bernard Bousmanne, curator of the Verlaine exhibition, said: “Verlaine wrote some of his best, if not the best, poems while in prison. Verlaine knew Oscar Wilde and they liked each other a lot, and there are parallels in their stories. However, while prison destroyed Oscar Wilde and he never wrote anything significant again, prison was a key time in Verlaine’s life in terms of creativity.”

On the outside, little has changed at the public prison in Mons. On 25 October 1873, it was a relatively new building when the horse-drawn police wagon transporting the convicted poet was driven through the massive wooden gates at the start of a two-year sentence. In what became known as L’Affaire de Bruxelles, Verlaine, just 28 years old, was convicted of attempting to murder Rimbaud, then 18, for whom he had abandoned his beautiful young wife, Mathilde, and only child, Georges.

The men, who had a violent, drink-fuelled relationship, had recently returned from self-imposed exile in London, where they had enjoyed the delights of the French quarter in Soho. They were staying in a seedy hotel in the Belgian capital. After yet another drinking session, a row erupted. In the drunken altercation that followed, Rimbaud said he was leaving and Verlaine pulled a pistol and fired twice. One bullet hit the floor; the other Rimbaud’s wrist.

Verlaine was arrested as he pursued Rimbaud to the railway station. When police searched both men, they found letters written to each other and Verlaine was subjected to a humiliating body search by a police doctor who wrote: “P. Verlaine bears on his person traces of habitual pederasty, both active and passive.”

Other police reports stated: “In morality and talent, this Raimbaud (sic), aged between 15 and 16, was and is a monster. He can construct poems like nobody else, but his works are completely incomprehensible and repulsive.”

According to Bousmanne, “Verlaine was not convicted because he was homosexual, because this was not a crime, though it was considered deeply inappropriate behaviour. On the face of it, he was jailed for ‘attempted assassination’ because he had shot his lover, but he was clearly not trying to kill Rimbaud, who in any case never complained and did not want him convicted, so this was clearly an excuse. In my view, what counted more against him was that he was homosexual and a Communard [someone who took part in the 1871 Paris Commune insurrection against the government].”

Once jailed, Verlaine wrote to Victor Hugo asking him to intervene. Hugo replied that Verlaine should show “patience”, but in writing to the poet he inadvertently helped him. “Of course, Hugo could do nothing, but when the prison governor saw that Verlaine had a letter from Hugo, a true giant of French literature, he would have been impressed and it would have made life easier for Verlaine,” said Bousmanne.

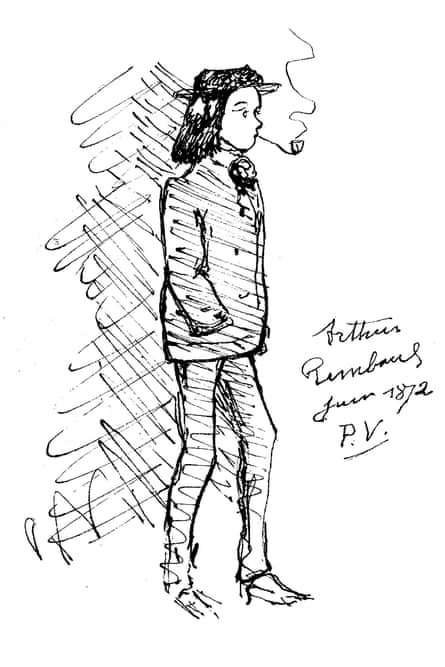

Bousmanne has spent five years combing Europe for Verlaine-related material and is particularly proud of a previously unseen photograph of the poet as a 22-year-old, which he found hanging in the kitchen of a Belgian farmhouse, and the revolver that Verlaine used to shoot Rimbaud, having bought the Le Faucheux 7mm six-shot revolver for 23 francs (the average monthly rent was six) just weeks before the shooting. “This has to be the most famous gun in French literature,” Bousmanne said.

The exhibition also includes 80 documents from the police and court files. “We can see from the legal documents that the judge, Théodore ‘t Serstevens, focused on his homosexuality,” Bousmanne added. On his release in January 1875 from Mons jail, where he was met by his mother, Verlaine travelled first to France and then returned to England, where he worked as a French, Latin, Greek and drawing master at various schools. He returned to France where, officially separated from his wife and son and missing Rimbaud, who had gone abroad, his life became a slow descent into poverty and alcoholism.

“Twenty years after he was released from Mons jail, Verlaine came back to Belgium at the request of the biggest writers here to give a series of conferences. By then he was an alcoholic and in a terrible state,” Bousmanne said. “Here was someone considered the most important French poet, and people were expecting the messiah to arrive. Instead here was this old man dressed like a down-and-out who was drunk. It was a shock to them.” The end of his life was spent in a drunken and destitute state, wandering between slums, hospital and cafes, countering treatment for diabetes, ulcers and syphilis with absinthe. He died of pneumonia in January 1896 at the age of 51.

Bousmanne says Verlaine has emerged as one of France’s four greatest poets – along with Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé and Rimbaud – but his violence towards his wife and mother suggest he was not a pleasant character, but a man who appeared to seek out misery and melodrama. “He is often moaning in his letters, but it was always someone else’s fault, never his. He often writes that he is going to kill himself or end it all, but doesn’t.”

Verlaine, Cellule 252: Turbulences Poétiques is one of the closing events of the Mons 2015 European Capital of Culture year. The exhibition opened yesterday 17 October and runs until 24 January

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion