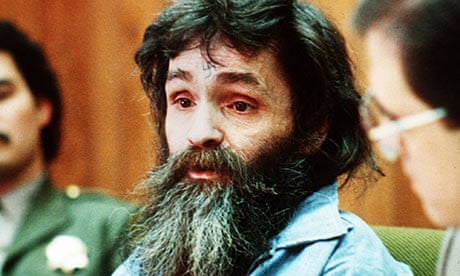

Back in 1986 the American news correspondent Charlie Rose travelled to a California jail to interview a monster. Seated behind a table, Charles Manson raged and rambled, rolled his eyes and waved his arms. On the one hand, he denied any involvement in the murders he had been convicted of masterminding. On the other, he stressed that there was actually no difference between life and death and that everyone is therefore as innocent or guilty as everyone else. At one stage Rose asked the prisoner just who he was, exactly. The man replied without missing a beat. "Charlie Manson," he said, "is whoever he's allowed to be."

Even as a child Manson was a genius at pulling strings and deflecting blame, either running from trouble or flummoxing his accusers with a saintly smile. He was the bad seed turned jailbird turned spiritual guru; the catalyst for a notorious 1969 killing spree that claimed the life of the Hollywood actor Sharon Tate among numerous others, selected almost at random. But what makes Jeff Guinn's biography so rich, knotty and gripping is the way it stitches the man into his environment. It shows how the humid climate of late-60s California harboured Manson and allowed him to flourish, at least on the fringes, at least for a while. And by the time it recoiled, the damage was done.

Manson left prison in the summer of 1967, torn between his twin ambitions of becoming a pop star and becoming a pimp. On the streets of Haight-Ashbury he was able to audaciously weld these dreams together, strumming his guitar as a park preacher in order to gather a flock of vulnerable young women and teenage runaways. Manson instructed his followers to shed their inhibitions and abandon their possessions. But all the while he was pocketing their earnings and employing the girls as sexual bargaining chips to secure his own advancement. Tellingly, he never claimed to be a hippy, preferring instead to refer to himself as a "slippy" – his jokey pun suggestive of someone who has slipped through the cracks of society, or snuck through the crawl-space to infect the house. Happily for Manson, the house was susceptible. In a series of deft chapters, Guinn paints a vibrant portrait of a listing, expanding California, rattled by war protesters and good vibrations, in thrall to circus barkers and Aquarian seekers. Amid the swirling detritus and buckling defences, it was briefly possible to confuse a pimp with a prophet and an apolitical sociopath for the second coming of Christ.

San Francisco provided the right conditions for Manson to settle, but it was further south where he reached full bloom. In Los Angeles he fell in with a fast-living celebrity crowd that included Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson and Byrds producer Terry Melcher, the pampered son of Doris Day. For one giddy spell, Manson's dream of pop stardom appeared to be just a whisker away. But his tunes were insipid and his sessions a disaster. The closest he came to chart success was when he wrote a song ("Cease to Exist") that was later rewritten and retitled as a Beach Boys B-side. The single bombed out at number 61.

As with Hitler and his oil paintings, it is tempting to posit some bizarre parallel universe in which Manson's dark ambitions took a different turn – in which he signed a record deal, found a measure of fame and was able to put his demons on a leash. Yet this seems unlikely. Guinn shows how his subject was always geared towards trouble; sooner or later, everything he touched turned sour. By 1969 his hopes of legitimacy were scuppered. He and the "family" had swapped a luxury berth at Wilson's pad for the less salubrious environs of the Spahn Movie Ranch outside town. There, behind the faded storefronts that once played host to the cast members of Zorro and Bonanza, Manson hosted LSD-fuelled orgies, read aloud from the Book of Revelation and played the Beatles' White Album on a constant loop, with particular reference to the sixth track on side three. "Helter Skelter", he explained, prophesied an apocalyptic race war in which black America would rise up to destroy the white ruling class. Then, after an unspecified period, his "family" would emerge from the rubble and take over the planet.

The nearer Guinn's biography draws to its central horror, the more it picks up speed. The middle section pitches us into the whirlpool, presenting a swirl of horrific gore and bubbling black comedy. The slayings are cooked up in haste, the motives so purely garbled that they amount to a kind of genius and leave the cops chasing shadows. The killers believe they are lighting the fuse that will make "Helter Skelter" a reality. Yet Manson has been whipped into a frenzy by other factors, too. He wants to take revenge on the Hollywood elite that rejected him. He wants to distract attention from his recent skirmish with a drug dealer. Perhaps he even spies a final chance of rock'n'roll stardom. The ensuing trial, he decides, will provide the ideal launchpad for his debut album.

If Guinn's book has a flaw, it is that Manson – for all his clamorous bustle and toxic charisma – remains a cipher. We are never entirely certain how much method is in his madness, nor whether he actually subscribes to the theories he spouts. Maybe this is because the man himself (now 78 and residing at Corcoran state prison) refused to grant an interview.

More likely it's because there was never much inner life to begin with. The Manson who emerges from these pages is a pure opportunist, amoral and depthless. He gulled others into believing he was bigger than Jesus. He gulled himself into thinking he was bigger than the Beatles. Barely anyone, it seemed, saw Manson for what he really was: a career criminal, one-part pimp to one-part imp; the bespoke vermin of the American counterculture. He crawled inside and built a nest.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion