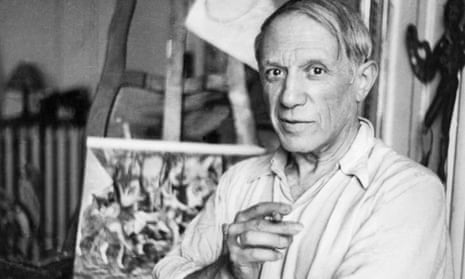

Picasso, giant of art, dies at 91

By Jackie Leishman

9 April 1973

Pablo Picasso, died in the south of France yesterday. He was 91 and had been ill for some weeks. A doctor called from the small village of Mougins, near Cannes, early in the morning said: “It was already too late when I arrived.” The cause of death was given as lung congestion.

With Picasso when he died were Jacqueline, his third wife, whom he married in 1971, his oldest son, Paolo, his secretary, and several close friends. The Spanish-born artist had lived most of his working life in France. He left Spain at the time of the civil war and vowed not to return until the restoration of the Spanish Republic.

Guernica, his most famous work, which now hangs in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, was inspired by the bombing of the little Basque town of Guernica.

After the second world war, Picasso made his major political gesture by declaring his allegiance to the Communist party. He produced many anti-war pictures like Korean massacres and the two great panels, War and Peace. At the same time he designed the dove symbol, the famous dove of peace, for the communist-led World Peace Congress in Paris in 1948.

Picasso’s output was enormous – he sometimes painted up to seven canvasses a day – and it does not seem to have dwindled in the last few years. Major paintings of the latter years have been sold for up to £200,000, but his work took in also engravings, drawings, sculptures, and pottery.

It has been estimated that in his lifetime Picasso produced at least 14,000 paintings and drawings, 100,000 prints, 24,000 book illustrations, and 300 models and sculptures. His last three years’ work represents more than the total works attributed to Michelangelo. His personal fortune has been estimated at £22m in paintings and real estate. News programmes on Spanish radio and television opened yesterday with the news of Picasso’s death, but there was no official reaction to the announcement.

Picasso – the end of an age

By Lawrence Gowing

9 April 1973

If ever an artist shaped an epoch it was Pablo Picasso. He was the major influence, immediate, and indirect, on the styles of the time. He moulded his vision, yet it was he more than anyone who destroyed the visual convention of the 19th century. In its place he restored to art a transforming magic, and a fantastic fertility that spread far beyond art until hardly anything in the imagination and the taste of the century was untouched by it.

His own way remained private, capricious, and passionate. For him (and thus in time for nearly everyone) the seriousness of art no longer lay in its sensible gravity. The artist seemed to be at play. Equipped with an incomparably brilliant talent, Picasso played with art, teasing it callously, mimicking its poker-faced consistency and its comic repeating tic. He teased it to death and it collapsed, breaking in pieces as it fell. In the first half of the century, the fragments littered the scene, ready to hand and ready for use. He used them first in a pattern, the wit and the jazz that were the elements of the new creativeness, until they rearranged themselves in metamorphoses which grew in turn grotesque and tragic, with an enormity that matched the horror of the time.

Picasso has epitomised a mood in which love and destructiveness often seem inseparable. Much of the character of art and thought in the 20th century has been due to the enigmatic nature of this one genius. For Picasso himself there was no contradiction; his demolitions recovered for image-making a quality of instinct, for him a picture was as a part of the impulsive natural world. The best summary of his art was Daniel Kahnweiler’s remark, “les objets sont ces amours.” If Picasso abolished the visual habit – “as they put out the eyes of goldfinches to improve their singing,” he explained – it was at root because only the alternative satisfied a terrific sensuality in him. “At bottom,” as he said, “there is nothing but love. No matter what kind.” Picasso’s kind was every kind. Discovering it we come very close to the creative spirit of the century.

Picasso to lie in chateau grave

11 April 1973

Pablo Picasso was brought to rest early today in the isolated 16th-century chateau of Vauvenargue which he bought 15 years ago but only visited twice.

Only his 46-year-old widow, Jacqueline, his son Paulo and a few relatives from Spain were present when the body of the artist was brought 60 miles from his villa Mougins and placed in the crypt of the chateau. The cortege arrived shortly after dawn. There was no religious funeral. Picasso was an avowed communist and the village priest was not invited to the internment.

The master’s pieces: Picasso’s bequest

By Caroline Tisdall

13 April 1973

News of Picasso’s bequest to the French nation of his vast collection of works by other artists has aroused great excitement and even greater speculation. For although he is known to have accumulated more than 800 pieces, many of them masterpieces by his own contemporaries, no one is sure of the full extent of the collection.

Picasso collected like a magpie buying what took his fancy. In the same spirit he never hung his treasures systematically but kept them piled against the walls and stashed in trunks in the villas in Mougins and Cannes. He would pull out particular favourites to show friends, but no one ever saw them all. As his friend Sir Roland Penrose says “It’s not like any ordinary millionaire’s collection of pots. It will also throw light on his interests and his work, which makes it imperative that the collection be kept together.”

Read the article in full.