When I press the buzzer of what looks like an old steel warehouse in the Parisian suburb of Malakoff, a faint voice responds. “To the garden,” it instructs. I push a heavy metal door and step inside a dark hallway. “Over here,” the voice calls. “Can you see me?” The voice belongs to Sophie Calle, one of the most influential artists in the world today, a woman whose four-decade career spans video, writing, photography and strange rule-based scenarios, often featuring detective-like attempts to get closer to people and places. Her work is populated by fortune-tellers, strippers, lovers, heartbreakers, sleepers, dying family members and blind people discussing their vision of beauty.

In a well-tended back yard, Calle greets me nonchalantly, a pair of oversized tinted glasses perched on her nose. She gestures towards the sliding windows leading to her home studio, housed in a building she remodelled in the early 1980s with her friends, the artists Annette Messager and the late Christian Boltanski. A black cat she calls Milou tries to catch up with her glazed orange leather boots. I follow them inside where, to my surprise, I find myself suddenly being stared at by a menagerie of stuffed animals. Each specimen is named after one of the artist’s loved ones: a tall giraffe bust for her dead mother Monique; a green monkey for the writer Hervé Guibert; a teeth-baring wolf for her gallerist, Emmanuel Perrotin. Membership of this exclusive club is, apparently, much sought after.

But there’s something else Calle wants to show me. In a corner of her studio, she opens an old suitcase filled with chipped red enamelled plaques. They once served as room numbers at the Hotel d’Orsay, part of the old railway station before it was turned into one of Paris’s best-loved museums. The 68-year-old artist salvaged them in the late 1970s while squatting in a room of the then disused hotel. Over the course of two years, she roamed its innards collecting relics, from rusty keys and customer records to cryptic messages addressed to a Beckettian figure named Oddo.

“I just took whatever came to hand,” says Calle. “And I kept everything. I don’t think I ever said to myself, ‘Hey, that’s going to be useful!’ That seems impossible. The plaques were pretty and lively. But the notebooks with the water meter readings? I don’t think I ever thought, ‘Well, I know what I’m going to do with those!’”

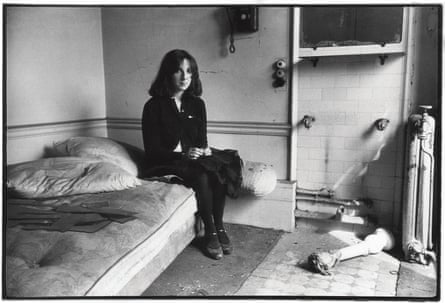

What she has now done with all these relics is return them to their original home. This week, the Musée d’Orsay – otherwise known for its collection of impressionist and post-impressionist masterpieces – is opening a solo exhibition chronicling Calle’s formative years as a non-paying guest. Titled Les Fantômes d’Orsay, or The Ghosts of Orsay, the show features about 300 items: a 19th-century chiming doorbell and a Haussmann-like lock with a copper handle rub shoulders with black and white pictures of a young and shy-looking Calle sitting on a filthy mattress, as well as recent eerie photographs of the empty museum taken during lockdown.

“I was lost,” says Calle of her squatting days, while sipping a coffee. “I had just come back to Paris after being away for seven years.” She had briefly studied sociology at the city’s Nanterre University, then an activist hotbed in the wake of the May 1968 protests, but quickly lost interest. Her oncologist-cum-collector father Bob had pledged to financially support her as long as she passed her exams. So she persuaded her professor – Jean Baudrillard, whose theory of simulacra inspired The Matrix – to mark her papers favourably while she went off travelling the world.

“He put my name on other students’ papers so I could travel and still get my degree,” she says, bringing her cup to her lips. “Merci, Jean!” She never bothered to collect the degree she thinks she earned. “I’m pretty sure I have a master’s in sociology,” she says. “It was never any use to me. I never intended to be a sociologist.”

Calle returned to Paris at the age of 25, not knowing what to do with herself. “So I started following strangers in the street. I thought they would take me to new and unexpected places.” This became her way of reconnecting with the city – a method she complemented with photography, in a bid to please her father (who approved of the medium) and thereby secure her monthly allowance. “It wasn’t so much the people that interested me,” she says. “It was Paris.”

At this point, Calle suddenly exclaims: “Wait! I’m drinking your coffee!” She offers to make me another, but I tell her I don’t mind hers, despite the sugar. “Just don’t stir!” she advises.

During one such expedition, she came across a door on the left bank of the Seine. “I don’t remember what it looked like. I can’t find any photos. But I imagine it must have been very small. I like small doors in big places. I always find them quite moving.” It was connected to the hotel of the former Gare d’Orsay, a beaux-arts building that had fallen out of favour.

“So I walked in,” says the artist, who found herself inside an empire of dust. “The atmosphere was a bit disturbing. It was totally abandoned. There were dead cats and noises and there was no light. It was a gigantic, totally empty place. I took it slowly.” She remembers ascending a split staircase and, over several days, proceeded to explore its five storeys and 370 damp rooms covered in decrepit wallpaper. The latter has been recreated for the exhibition, but in a modernised version.

Calle set up camp in room 501. “It was a place where I could go and be alone to do what I wanted.” When she wasn’t curled up with a book on a bug-infested couch, or photographing dead cats elsewhere in the building, she would go for a twirl under the gilded ceilings of the ballroom. “It was an amazing ballroom and had been left intact. At the time, I had loved a play by Robert Wilson in which dancers spun around like dervishes. I said to myself that I wanted to join a troupe, so I decided to practise spinning.” At dusk, unable to cope with the dark and the insects, she would walk back to her father’s place.

Rather than a period of confusion, Calle’s Orsay days were where she found herself and truly came into her own. In February 1979, one of her regular stalking sessions famously led her to Venice where, armed with a Leica camera and a blond bobbed wig, she shadowed a man for 13 days. This resulted in a book, Suite Vénitienne, which was later converted into gallery-based works: surveillance-like reports, creepy annotated maps and strangely seductive black and white photographs imbued with a voyeuristic quality.

Back in Paris, she recruited a variety of people to sleep in her bed at her father’s place. For eight consecutive days, 28 participants – her mother, neighbours, distant acquaintances – lined up to donate eight hours of their sleep while Calle photographed them. One sleeper’s husband – a critic and curator – was so taken by the project he invited Calle to show the resulting 176 photographs and 33 texts at the Paris Biennial, at the Musée d’Art Moderne. “It’s he who decided that I was an artist,” she says. “I had only pretended I wanted to be a photographer so that my father would lodge me.” Visibly amused, she adds: “The day I came to hang my pictures was the first time I ever stepped inside that museum!”

But later that year, when she returned to her squat from a summer holiday, she found a building site at its entrance. She walked straight in, greeting the builders confidently, and retired to her quarters. “They were invading my territory,” she remembers. Little did she know that her precious hideout was being turned into what would become a world-class museum. “The day I found an architect on the fifth floor, I knew it was the end. I left and never went back.”

When I suggest that, appropriately, themes of hospitality dominate her early works, her smile fades into a frown. “Non!” she says, as Milou starts chewing on my pen, which I take as a warning. “The obsession is rather with absence: an empty hotel, rooms in which there are no customers, following a stranger who isn’t really there, and then people who die, people who leave.”

This is a reminder that Calle came of age in the heyday of psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, whose theory-filled seminars about le manque (“lack”) and la pulsion de mort (“death drive”) dominated Paris’s cultural life. Growing up in the 14th arrondissement, she enjoyed spending time at Montparnasse cemetery – the final resting place of the French intelligentsia, from Charles Baudelaire to Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. Both her parents are now buried there but Calle, unable to secure a spot, got herself a place in Bolinas, California, instead. “The cemetery was the green space of our neighbourhood,” she says. “We lived 100 metres away and my school was on the other side. So that was the first place in Paris I appropriated.”

Just as Calle is telling me that she’s now working on a project involving her will, a loud miaow erupts from somewhere in the background. As I scan the room for Milou, Calle tells me the noise was in fact a phone notification that sounds whenever he leaves through his app-monitored flap. “We didn’t want to play with him,” she shrugs, “so he left.”

At the Venice Biennale in 2007, Calle received both praise and criticism for showing an 11-minute film that documented the final moments of her terminally ill mother’s life. In a corner of her deathbed, the artist had placed a video camera that filmed for days. “I wanted to be with her,” Calle says. “I said to myself that I had to be there all the time, in case she had something to ask me before she died – something, a story, to tell me.”

Changing the tape every hour became Calle’s way of reclaiming the time she had left with her mother – a way of taming death. “Instead of counting the hours she had left to live, the tape became my obsession. The time passing had become that of the cassette and no longer that of her life. So I could go out without being afraid – I felt like I was always with her. I think, for her too, she felt I was always there. She told me she liked the presence of the camera.”

Much like the Orsay objects, Calle never intended to use the footage, until the US curator Robert Storr – then in charge of the biennial – got wind of it and suggested making a film. “I said no,” explains the artist who feared the project would be too messy and unfocused. “It was out of the question.” But as Storr insisted, she gave in. “What really intrigued me was that I couldn’t detect death,” Calle says. “It was invisible. It was elusive. That intrigued me.”

When I ask what kind of ghost Calle would like to be, she pauses then says: “Maybe a cat at my friends’ house. A cat that hears and understands everything. But in any case – a ghost who can spy.”