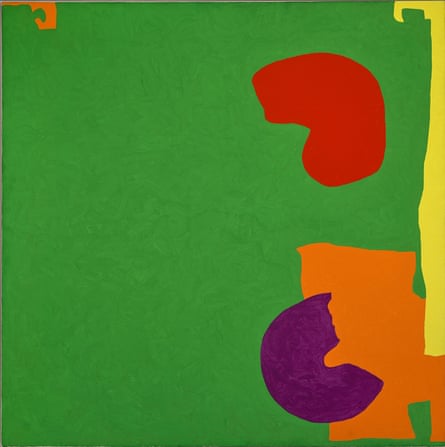

Patrick Heron’s Cadmium With Violet, Scarlet, Emerald, Lemon and Venetian: 1969 has about the most prosaic and cumbersome title of any work of art I know: say it aloud, and its pedantry and precision sound close to comical. But to stand before it – all 80 or so square feet of it – is to experience a powerful sense of exaltation. This is a painting that seems so absolutely right, falling on the enthralled visitor, to pinch from Philip Larkin, like an enormous yes. Its colours, its shapes, its scale: what incredible joy and heat these things stir up. From a distance, I stared at it, and thought of something I liked to do as a child, which was to lie on the ground in warm sunshine, and close my eyes, and wait for swirling patterns of rose-red and gold to appear on the inside of my lids. Suddenly, for a fleeting moment, I was that child again.

But there’s more. Stand well back, and Heron’s great mid-period works, painted in the late 60s and early 70s, have a blocky feel, the oil seemingly so smoothly applied, you wonder what thinner he used, what kind of airbrush. Move closer, though, and the ground shifts beneath your feet. Unbelievable as it sounds, these vast canvases were painted end to end with small Japanese watercolour brushes, and once you’re only a few inches away, everything looks at once rougher and yet more beautiful: here are patterns within patterns, a delicacy that is in almost total contrast to the painting’s overall effect. Do the two things work together? Heron certainly believed that they did. “One doesn’t hand-paint for the sake of the ‘hand-done’,” he said. “One merely knows that surfaces worked in this way can – in fact, they must – register a different nuance of spatial evocation and movement in every single square millimetre.”

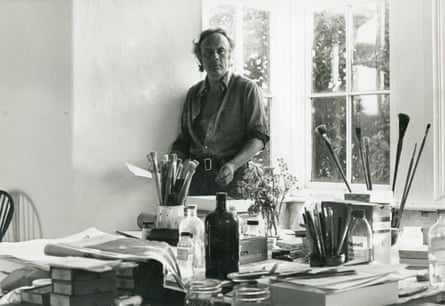

This extraordinary painting, and several others from the same era, form the heart of a major exhibition of Heron’s work at Tate St Ives. It’s easy to see why the Tate wanted to show Heron (1920-1999) here, in its new galleries’ first summer. Not only did the artist live and work for more than 40 years in a house called Eagles Nest nearby on the west Penwith peninsula; the bigger and more colourful of his canvases are extraordinarily well suited to these hangar-like spaces – effectively chiselled into the hillside behind the gallery’s original rooms, they are nevertheless both vast and marvellously light – where the best of them seem to float like glorious planets in a concrete solar system. The curators’ approach to Heron’s work, however, is a less easy thing to explain. I must be honest: I find it utterly exasperating.

Andrew Wilson, a senior curator at Tate Britain, and Sara Matson, a curator at Tate St Ives, have taken a non-chronological approach, gathering Heron’s work into four wilfully vague and hard to understand themed groups: unity; the edge; explicit scale; asymmetry and re-complication. The idea is to show that the artist’s approach to painting throughout his life was “utterly consistent”, from the figurative work he produced in the 1940s through his move into abstraction in 1956, and beyond (his later work, which seems to me not always to be entirely successful, is very much concerned with mark-marking, and hovers in a liminal space somewhere between abstraction and figuration – even if Heron, who disliked such distinctions, would doubtless not have seen it quite like this). They also hope that by hanging paintings that were completed decades apart next to one another, visitors will be able to “experience” Heron’s work in a “non-didactic” way.

Are the experts afraid, in our present climate, of seeming too expert? Perhaps. Or perhaps they really believe this is the way to learn about Heron. If so, I think they are wrong. People are perfectly capable of learning about an artist and giving themselves up to his talent; this, in fact, is what most of us actively long for when we visit a gallery. Nor are we goldfish. We can remember a painting from, say, 1943, for the 20 minutes it might take us to pitch up at one made in 1996, for which reason we’re capable of spotting certain convictions and repetitions on the part of the artist on our own. A chronological show would have been so much better, and easier to grasp, revealing both the way Heron, the son of a manufacturer of silks, developed in the years after he left the Slade, and the formal consistency to which he was so committed. As it is, it’s a jumble, its focus obscure, its motivation patronising.

Still, put aside your frustration, and there are wonders all about. The earliest work is The Piano (1943), a small oil on paper depicting a window, a grand piano and various objects balanced on it. In a way, it’s perfectly ordinary: so many artists were then making work just like this. But it comes with a whiff of Bloomsbury that reminds you of Heron’s other, secondary vocation as a writer about art in the tradition of Roger Fry. And it underlines the fact, entirely lost here, that when Heron and the likes of Victor Pasmore slipped into abstraction in the 1950s, it really was an art world drama, for all that it seemed to them to be so seamless, a wholly natural thing. In this context, Christmas Eve (1951) appears as a kind of bridge between the two modes. Here is a fuggy, frenzied room, all children and candles, only you have to get your eye in to see it, and its colours have to do with summertime rather than winter.

Heron’s early adventures in abstraction have an experimental feel, as if he’s working something out. “The reason why stripes sufficed,” he said of Green and Mauve Horizontals: January 1958, “was precisely that they were so very uncomplicated as shapes.” Much more exciting to me is Camellia Garden: March 1956, a dappled vista that suggests so powerfully an abundance of blood red and pale primrose petals, you’re half-tempted to sniff the air. After this, however, a great leap forward (again, neither he nor the curators see it like this). He has the chutzpah of the great Americans (Pollock, De Kooning), but his face is turned resolutely towards France (here, most of all, is Matisse). Impossible not to come over a little swoony in the presence of Square Green with Orange, Violet and Lemon: 1969 and Complex Greens, Reds and Orange: July 1976 - January 1977 with their fascinating patterns, their almost violent juxtapositions of colour. Give them the time, and they seem almost to hum, their good vibrations filling you quite blissfully with thoughts of life and love and liberty.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion