Ralf Winkler, better known as AR Penck, claimed never to have heard of conceptualism at the start of his five-decade career. Despite this, the German artist’s early Standart body of work, developed in isolation behind the Berlin Wall during the late 1960s, chimed with the emerging avant-garde tendencies of his western contemporaries. Like Lawrence Wiener and Joseph Kosuth, Penck, who has died aged 77, sought to develop a system uniting art and language that addressed complex sociopolitical themes; but unlike those American conceptualists, he did so using a primitive, almost childlike, imagery.

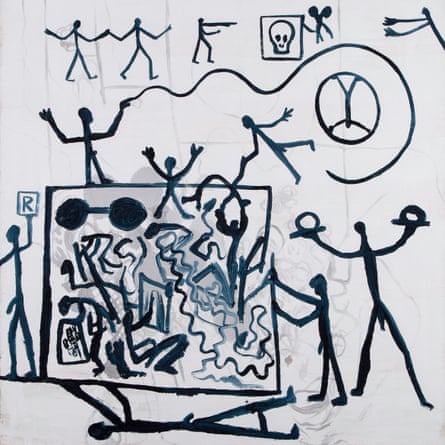

Paintings in the Standart series featured a rudimentary stick figure, a motif that would become central in his work. Blank-faced and stiff-bodied, they were often depicted with crudely drawn male genitals against an abstract background. A stick man dominates the frame of a 1971 painting, for example; daubed in black acrylic it stands against a riotous background of red circular splodges and rectangular markings. A couple of further primitive-style motifs interrupt the expressionist paint handling. An untitled work from 1968 shows a similar figure, stretched to appear almost comically thin. A circle, square, star and other symbols surround the human figure.

For Penck, the stick figure, though a motif that dates back to cave art, represented the first ideogram of a proposed new system of communication that combined text, symbol and image. Standart was a conflation of the English word “standard” and the German Standarte, meaning “banner”. For the artist, these works operated like flags, emblematic of human universality. Penck’s interest in networks, and a prescient desire for the unhindered flow of ideas between individuals, also led to an interest in early computer technology. A 1968 oil painting on board, titled Primitive Computer, proposed a new 45-symbol alphabet for the coming information age.

“Every Standart can be imitated and reproduced and can thus become the property of every individual,” Penck wrote in 1970. “What we have here is a true democratisation of art.” These paintings, and the accompanying sculptures, often made from discarded rubbish (as art supplies were scarce and often restricted in the German Democratic Republic), were smuggled to West Berlin, where they gained an immediate audience.

In his work Penck both embraced the utopian essence of socialism – he was one of the few of his peers to initially stay in East Berlin after construction of the wall in 1961 – while reflecting the harsh realities of the state’s authoritative regime. A work from 1969, painted on a blanket, depicts another crude figure in blue trapped within a bulkier counterpart in black. Simply titled Standart, it brings Penck’s creeping interest in existentialism and alienation to the fore, and it is perhaps natural that a cold war audience would find succour in allusions to claustrophobia and uniformity.

Born in Dresden in 1939, Ralf witnessed the devastation wrought on the city in the final months of the second world war. It was a trauma he would later evoke in the violent, fiery red, painting Umsturz (Coup d’Etat, 1965).

From 1953 to 1954 he studied painting and drawing with the film director and painter Jürgen Böttcher at a community college, and the following year he started an apprenticeship as a draughtsman with Dewag, an advertising agency in his home city, before moving to East Berlin with hopes of attending art college. Despite his evident talent, he was repeatedly denied admission, possibly because of the “dissident” nature of his work, and so found work as a postman, steam engine stoker and night watchman while privately making paintings, sculptures and music.

In 1957 he met Georg Kern, soon to change his name to Baselitz, the year the latter was kicked out of art school in East Berlin for “sociopolitical immaturity”. Baselitz would later attend college in West Berlin, where he had a one-man show in 1963 at a space run by the gallerist Michael Werner.

In 1964 Penck moved into his own studio on Lange Strasse in Dresden, and made his first Standart work. From 1968, on meeting Werner, the artist also began illicitly exhibiting in the west, with the first show at Galerie Hake, Cologne. To avoid the unwanted attention of the state he used a variety of pseudonyms, including “Mike Hammer”, “TM”, “Mickey Spilane”, “Theodor Marx”, “a. Y” and just “Y”. It was “AR Penck”, adopted after reading the work of the geographer and geologist Albrecht Penck, that stuck.

He had his first solo museum show at the Museum Haus Lange in Krefeld in 1970, but in 1973 his real identity was discovered and he was thereafter dogged by visits from the Stasi and kept under observation. He also had to do six months training for the People’s Army. Yet he continued working and showing in the west, being given a retrospective at the Bern Kunsthalle, Switzerland, and winning the Will Grohmann prize of the West Berlin Academy of Arts (both 1975). The harassment came to a head in 1979 when his studio was raided and its contents destroyed. The following year, he escaped to West Berlin.

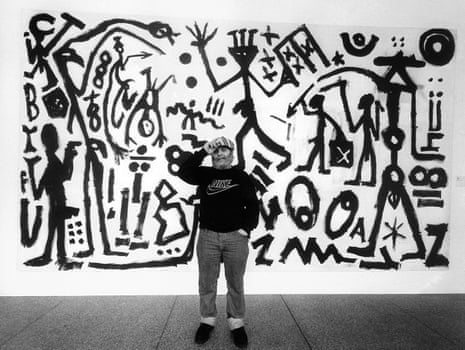

In this period, from the late 1970s onwards, Penck flourished. The work he made while moving between West Berlin, London, Dublin and New York was more colourful, with a greater sense of joy in its use of pattern and repetition of form. Friendships with artist fellow countrymen Markus Lüpertz and Jörg Immendorff as well as Baselitz led to his naive, semi-abstract style being grouped with theirs, part of a movement later dubbed neo-expressionist. His work was included in the groundbreaking Zeitgeist show at the Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin (1982), A New Spirit in Painting at the Royal Academy of Arts (1981) and New Art, Tate (1983), in London, and the 1984 Venice Biennale, as well as in four subsequent editions of the quinquennial Documenta exhibition in Kassel. His international reputation was secured.

From the early 80s to the mid 90s he drummed in a jazz band named Triple Trip Touch and, when speaking of his later painting, made frequent reference to the freeform musical style.

His work fell out of favour after his 80s heyday, but in recent years regained relevance and is seen as an influence on many contemporary artists. In 2007, his work was the subject of a retrospective at the Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, and there is currently a solo show of his work, Rites de Passage, at the Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul de Vence, France.

He leaves his wife and children.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion