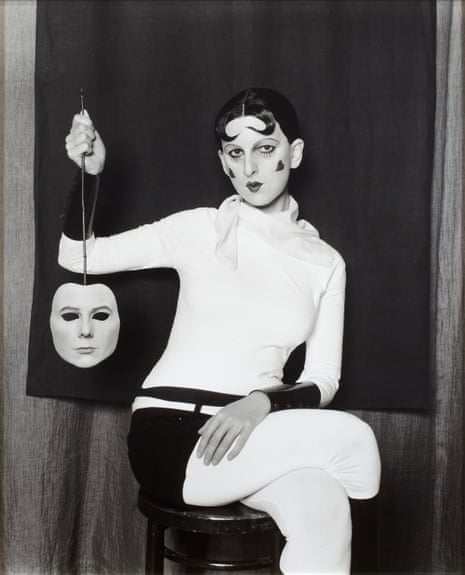

With hearts on her cheeks, kiss curls on her forehead and cupid’s bow lips, Claude Cahun stares out at us in a small black and white photograph, taken in 1927. Her gaze is steady. Do you dare look at me, she seems to say, meeting the photographer’s gaze. The phrase I AM IN TRAINING DON’T KISS ME is emblazoned on her leotard. Her outfit makes me think of a circus act.

Cahun was one of the few women surrealists in André Breton’s circle. Born in Nantes in 1894, partly educated in Surrey, Lucy Schwob became Claude Cahun in around 1919, and lived with her life-partner and artistic collaborator Marcel Moore, whose given name was Suzanne Malherbe, for the rest of her life. In 1937 the couple moved to Jersey, working in the resistance during the German occupation, and were caught, imprisoned and sentenced to death in 1944. Released when the Channel Islands were liberated the following year, Cahun died in 1954.

Here is Cahun again in an almost identical pose. The same kiss curls, the same pout. But this time the image – on a far larger scale – is by Gillian Wearing, and dated 2012. The likeness and the dislocation are unnerving. In her photographs, Cahun depicted herself in multiple guises – middle-aged man, shaven-headed androgyne, cloaked and masked, cross-dressed, bleach-haired in a mirror. “Behind this mask another mask, there can be no end to these disguises,” Cahun wrote.

Behind a mask, Wearing is being Cahun. Previously she has re-enacted photographs of Andy Warhol in drag, the young Diane Arbus with a camera, Robert Mapplethorpe with a skull-topped cane, hard-bitten New York crime photographer Weegee wreathed in cigar-smoke. Among these doubles, you know Wearing is in the frame somewhere, under the silicon mask and the prosthetics, the wigs and makeup and the lighting. Going through her own family albums, she has become her own mother and her father. It is a surprise she has never got lost in this hall of time-slipping mirrors, among her own self-images and the faces she has adopted. Wearing has got others to play her game, too – substituting their own adult voices with those of a child, putting on disguises while confessing their secrets on video.

Cahun was almost forgotten until the late 1980s, and much of her and Moore’s work was destroyed by the Nazis, who requisitioned their home. What remains – mostly in the collection of Jersey Heritage Trust – is an astonishing archive. Moore killed herself in 1972, and she and Cahun are buried together in a Jersey churchyard. Wearing visited the spot last year, and made a further series of new images.

Cahun has been described as a Cindy Sherman before her time. Wearing’s art undoubtedly owes something to Sherman – just as Sherman herself is indebted to artist Suzy Lake. Looking back at Cahun, Wearing is both tracing artistic influence, and paying filial homage to it, teasing out threads in a web of relationships crossing generations.

This March, the National Portrait Gallery in London brings the work of Cahun and Wearing together for the first time. Slipping between genders and personae in their photographic self-images, Wearing and Cahun become others while inventing themselves. “We were born in different times, we have different concerns, and we come from different backgrounds. She didn’t know me, yet I know her,” Wearing says, paying homage to Cahun and acknowledging her presence. The bigger question the exhibition might ask is less how we construct identities for ourselves than what is this thing called presence?

- Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun: Behind the Mask, Another Mask is at the National Portrait Gallery, London, 9 March-29 May

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion