It’s one of those miserable cement-gray December afternoons in Manhattan when no one wants to leave the house, so of course there’s just one other person in the Greenwich Village restaurant where Julianne Moore and I meet for lunch: a petite older woman having a pot of tea. Even so, the construction noise outside is distracting. Moore gets up to ask the host if there’s anything we can do to improve our chances of hearing each other, when suddenly squeals of reunion abound. I can hear snatches of the conversation — Moore updating the stranger on the sizes and ages of her children (so big!), the welfare of her husband (really good!), how everything’s been (not bad!). In the 40 seconds since we last spoke, Moore discovered the tea drinker is actually one of her friends: the Emmy- and Tony-winning actress Blythe Danner.

The two worked together on 1997’s The Myth of Fingerprints, the same film on which Moore met her husband, Bart Freundlich, who directed it and with whom she has two children: Cal, 26, and Liv, 21. Seeing Danner was a full-circle moment — she was there when the seeds were planted. Chance run-ins like this, the city’s tendency to lob memories at you when you least expect them, are exactly why Moore loves her life in New York so fiercely. She has lived in Manhattan since 1983 (save for a few years studying abroad in Los Angeles in the ’90s), when she moved to a building on East 38th Street, an address that made everyone assume she worked at the airport since it was so close to the Midtown Tunnel. A waitress back then, Moore was obsessed with creating her own luck: If she could leave the house at precisely the same time every day, after having exactly two cups of coffee, and take the same route, choreographing her movements so she never had to wait at a stoplight, she would have a good day at work. She called this “the lucky way.” For fun, she would wander around Manhattan, taking long walks up the East Side; she would buy a $5 plate of chicken lo mein from a spot on 37th and Third and stretch it out for lunch and dinner or show up early at the restaurant to take advantage of her shift meal.

Forty years later, nearly everything in the city reminds Moore of something else, she tells me. In Central Park, she remembers being in her 20s, in cabs returning from the airport, watching all the lights pass through the window; whenever she’s on FDR Drive, she thinks about early mornings in her 40s darting from her apartment on 11th Street to drop off Liv at school. “The great thing about being here for such a long time is that you watch these different iterations of New York appear and disappear,” she says. We’re sitting a stone’s throw from the historic gay bar Julius’, where Moore has watched the Oscars with her daughter; a few blocks north of 260 Spring Street, where she went to The Row’s sample sale a few weeks ago and ended up buying a pair of shoes that turned out to be a totally different color when she got home; and around the corner from Casa Magazines, whose owners, Mohammed Ahmed and Syed Khalid “Ali” Wasim, have known her kids since they were in diapers.

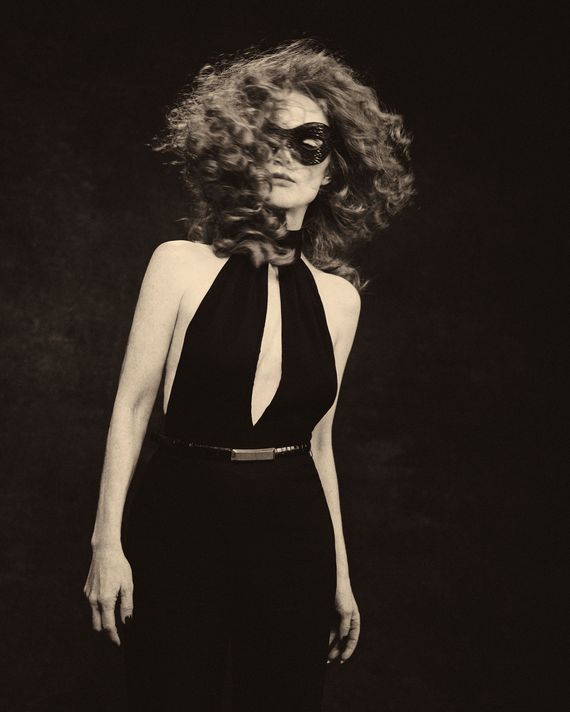

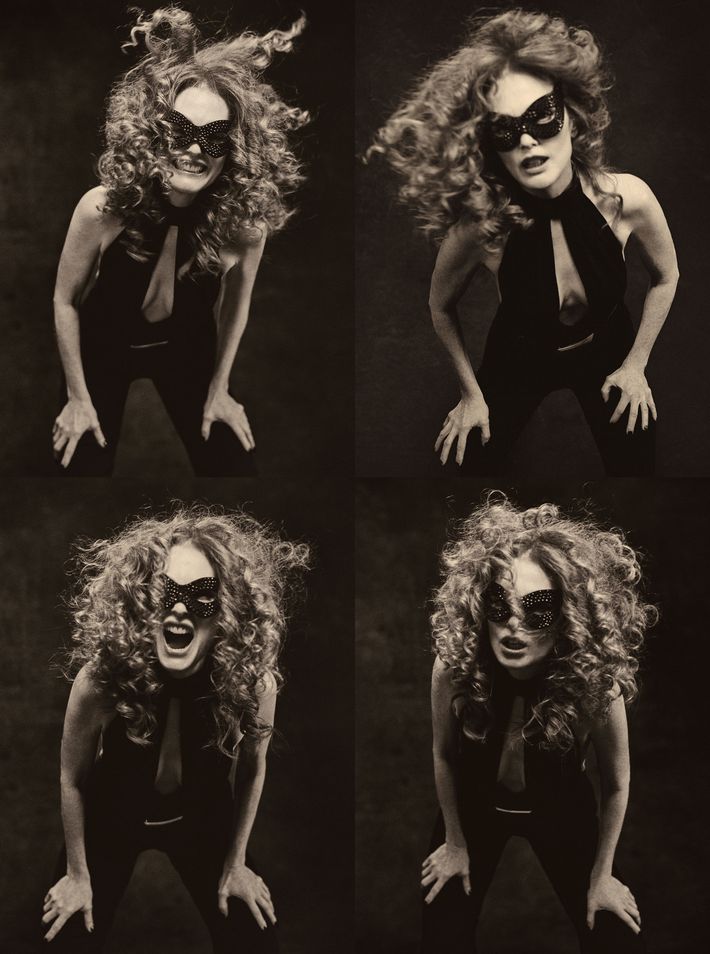

Spring Fashion Issue

Today, she is dressed in head-to-toe black with five or six gold rings catching the restaurant’s overheads. In real life, Moore, 63, is deliciously comforting, a massage of a person, with the sort of beauty that feels dreamed up by cosmetics executives or awards committees, painful not in its otherworldliness but in its proximity and potential — you could be this beautiful, but you simply aren’t lucky enough. As an actress, though, she reminds me of one of those ultrafeminine stealth defense tools, a dainty pink hairbrush that’s actually a stun gun. Her career is capacious enough to include everything from independent films that your liberal-arts cousin might cite (Safe, Short Cuts), to box-office hits that your dweeby younger sister adores (The Hunger Games trilogy, Dear Evan Hansen), to the OSCAR NOMINATED tab on Max (Boogie Nights, The Hours, Still Alice). Her characters tend to fall into two categories: the audacious — a porn star trying to regain custody of her child, cheaters, sex offenders, a mother who tries to fuck her son’s homosexuality out of him — and the domestic, women whose tragedies live on the vanity next to their perfume bottles or cool on the countertop next to that night’s dinner.

Her most memorable roles are some dangerous mixture of the two, and nowhere is that more apparent than in last year’s May December, in which Moore’s Gracie — a pedophile based on Mary Kay Letourneau who ends up marrying the adolescent she abused — is as duplicitous as she is delusional, a crybaby who might shank you with her favorite cake knife. The film was directed by Moore’s longtime collaborator Todd Haynes, and it revisits some of the pair’s favorite themes: femininity, identity, mythmaking, self-definition, perversely large glasses of milk. It helps, of course, that Moore is among the most versatile actresses alive, a different and more beguiling benchmark than “best” — she has the dexterity of a character actress but the looks of a movie star. In April, we’ll see her as a conniving countess selling out her sexually fluid son for status in the Starz miniseries Mary & George.

Moore tends to gravitate to the brave and the strange, people who are searching for an answer or women spilling over the edge, women attempting self-definition amid a suppressive force, seasick from the internal churn between who they are and who they want to be. Gracie is as much of a classic Julianne Moore role as any: a character who neither understands herself nor seems particularly interested in doing so. In this way, her characters aren’t too far off from the actress herself. We’re on our way out the door and having a meta moment about the impossibility of fully understanding another person. Pursuing an identity is a game for the young, Moore says; it gets harder, and less necessary, as time goes on. “I don’t think anybody ever knows who they are. So how are you going to know who anybody else is?” she says a little too readily. Self-knowledge is divine; constructing a narrative about yourself and sticking to it is the most human thing of all. She adds, “I mean, I barely know myself!”

Late in 1993, Moore arrived at 225 Lafayette Street in downtown Manhattan knowing exactly what to say. She had been in Pittsburgh filming Roommates, a sweet family movie in which she starred opposite Peter Falk, when she received Haynes’s script for Safe, a story about an upper-middle-class woman who believes she is slowly being poisoned by her environment and eventually ends up in a cult that masquerades as a health clinic. Moore was so moved by the script that she assumed the lead role had already been cast — and in a way, it had. Haynes had first offered the part to Jennifer Jason Leigh, whom he knew from high school. She passed, and Moore got right on a plane. She knew this Carol White, as enfeebled and needy as she was, right down to how she sounded, formulating a voice for the audition that was soft and high up in the throat with no weight on the larynx whatsoever, nowhere for her voice to sit. “I felt like it was very clear on the page. I could only see it one way, and I thought, Give it a shot,” Moore says.

She showed up for her audition in white jeans and a T-shirt, wanting to look as neutral and bland as possible. In one part of her tape, her character, now settled in the sanatorium, calls home to her husband, who tries his best to get off the phone. Even in the audition, Moore’s Carol is desperate without being pleading; you can hear her riffling through her brain for things to say to him, anything to stretch the conversation out longer. Moore read three scenes for Haynes, who was so blank-faced during the reading that Moore assumed she had whiffed it. Later, Haynes called it one of the most definitive experiences of his career. “Julianne heard the voice within that locked-up soul of a woman and made something incredibly tender and precarious out of that character that isn’t real until it’s real,” he says one day in January, the audition still as sharp in his memory as it was 30 years ago. “She brings that other side to what I am imagining in the dark.”

The Village Voice called Safe the greatest film of the 1990s, cementing Haynes as a filmmaker to watch and Moore as an actress who makes you have to cover your eyes. In the years since, Julie (what most people call Moore) and Toddie (what Moore calls Haynes) have become equal parts creative partners and soul sisters. Moore insists there’s something about their upbringing — they were born one month apart and were both raised by young parents with two other children — that allows them to occupy the same frequency, to the point that they barely rehearse when starting a film. Haynes writes a script and Moore hears it, almost immediately playing it back the way Haynes had imagined it in his head.

He describes her physical ownership of her characters as putting them into the present tense, “where you really feel the person’s tenderness and vulnerability right in front of you, and the voice registers in a certain place in the body that again keeps telling you about what that body must be going through and where that body is shut off and where it’s blocked.” In Safe, Carol starts off small and becomes smaller, eventually finding solace — and strength — sealed inside a hermetic environment in a space not much bigger than she is, but where she can finally gain control by giving up everything else. Toward the film’s conclusion, Carol tries to praise her experience at the sanatorium, babbling on about how self-actualized she has become: “I really hated myself before I came here, so I’m trying to see myself, hopefully, more as I am, more … um … positive, like seeing the pluses?” Her nod at the end feels like a shiver. We believe it only because we see how much she wants to believe it herself.

André Gregory, with whom Moore would later work in Vanya on 42nd Street, remembers finding Safe so disconcerting that he had to watch it in two sittings a week apart. “Her performance was one of the most frightening and heartbreaking performances I remember seeing,” he says. “It was almost as if it was a documentary of a woman ceasing to exist right in front of your eyes.” Moore became so committed to Carol’s emotional and physical emaciation that, after filming, she didn’t menstruate for eight months.

She went on to appear in four more of Haynes’s films, including his Bob Dylan not-quite-biopic I’m Not There and the young-adult adaptation Wonderstruck. Their best-known collaboration is likely Far From Heaven, Haynes’s 2002 homage to the Douglas Sirk genre films of yore. Haynes wrote it specifically for Moore, sending her the script with some sketches of how he thought the character looked. Moore plays a 1950s Connecticut housewife who strikes up a friendship with a Black man (Dennis Haysbert) while her marriage slowly unravels owing to her husband’s (Dennis Quaid) homosexual infidelity. It’s somehow both a tearjerker and a thriller. Moore is as luminous as she is unself-aware, her character looking to be saved while simultaneously blind to the danger that she poses to herself in transgressing racial boundaries. Moore was nominated for a Best Actress Oscar for the film — the same year she was nominated as Best Supporting Actress for The Hours.

Taken together, Haynes and Moore’s collaborative efforts are a curious study in the human condition, those ways we try to figure out how to be a person. “The miracle of Todd is that he has this unbelievable wealth of cinematic knowledge at his fingertips and has such a formidable intellect,” Moore says over lunch. His films ask the fundamental questions: “What does it mean to be a human being? What is identity? How is identity shaped by culture? Has it been shaped by gender? By language?” Just look at May December. In many ways, it’s a horror film, a nightmare sequence about an endless, fruitless search for an answer — in this case, to the question of whether we can understand a person’s motivations. “There’s something inherently mysterious about Gracie because Gracie will not give it up,” Moore says of her character. She gave Gracie a lisp in part because it reminded her of when a child is first beginning to talk and has, in a way, the accent of the freshly initiated, of someone figuring out where words go in the mouth. It’s a fitting characteristic for a woman wedded to her own sense of innocence.

As a creative pair, Moore and Haynes are less interested in whatever the truth is than the search to find it, luxuriating in the untidiness of a life. “Sometimes in movies, there is a truth, right?” Moore asks. The sorts of stories we get introduced to early on — cleanly delineated with a beginning, middle, and end — make us think real life can take on that same neatness. She says, “Everyone wants to be understood, but they also really want to be understood in the way that they understand themselves. Is that inherently the truth?”

The first time Moore’s mother, Anne, realized her daughter was beautiful was when she saw her onstage. Moore had been a homely child, covered in freckles, all gangly arms and legs, her head always in a book. She was a sweet kid but not necessarily a pretty one, with a plain-Jane name to match: Julie Anne Smith. (She later changed her name for SAG reasons.) The summer she turned 15, Julie Anne bloomed into puberty, losing the glasses and getting a good haircut. When she landed the title role in her high school’s production of Sleeping Beauty, her mother was shocked at who her daughter had become, nudging her husband and remarking, “Oh my God, Peter — she’s pretty.”

Born in Fort Bragg, North Carolina, Moore was raised by a military lawyer and a psychiatric social worker in nearly 30 places — as dissimilar as Panama, Alabama, Nebraska, and Germany. (By her senior year, her classmates, this time in Germany, had elected her to homecoming court. Halfway through high school, Julie Anne suddenly became popular, which was confusing. To her, all she had done was take off her glasses.) Wherever the family was, though, when they sat down at the dinner table, they invariably talked about human behavior, what people do and why they do it. As a kid who moves around a lot, “you’re always diagnosing behavior and learning it and adapting to it so that you can fit into it as seamlessly as possible,” Moore says, an impulse that is useful for an actor.

One of the few constants in her life, besides siblings Peter and Valerie, was the local library, where she inhaled books by Louisa May Alcott, Pearl S. Buck, Edith Wharton, Henry James, and Laura Ingalls Wilder, “anything that was about girls and self-determination,” she recalls. The theme still resonates. In 2007, Moore published her first children’s book, Freckleface Strawberry, titling it with one of her own childhood nicknames, which came from a brand of imitation-fruit drink mix. (Freckleface Strawberry is now the heroine of eight of the nine books Moore has written; the odd one out is called My Mom Is a Foreigner, But Not to Me, dedicated to the actress’s Scottish mother.) The main character is plagued by the cosmetic differences between herself and her schoolmates and the distance and discomfort they create. She encounters bullies, screws up her homework, and has to explain her freaky-looking lunch to a table full of nosy, booger-faced kids. She is, unsurprisingly, doused with freckles as generous as powdered sugar on a cake, and she somehow has too many and not enough teeth.

The book series explores many of the same themes as Moore’s films — alienation, panic, integration — and the lessons are simple and constant. Embrace who you are, all the ways you are distinctly different from everyone else yet also exactly the same. This is both Moore’s acting philosophy and her lesson to her own children: You don’t have to become someone else to understand them.

When Julie Anne was in high school, she and a friend were the only two girls in their class who didn’t make the drill team, so she auditioned for the school play to have something to do with her time. Acting, she discovered, was like reading. “I felt like I could hear it in my head,” Moore says. “It didn’t occur to me that not everybody felt that way. Being in a play, for me, was being in a book.”

Her drama teacher was the one who encouraged her to pursue the arts seriously. “What was amazing for me was having this older person acknowledging that I had any kind of ability,” she says.

Inspired, teenage Julie Anne took home a copy of Dramatics Magazine with listings of good college drama programs and announced to her parents that she was going to be an actor. (A version of her mother’s response found its way into May December: “Oh, Julie. Why waste your brain?”) She had never seen a professional performance of a play.

After graduating from Boston University and moving to New York, Moore waitressed until she landed on As the World Turns in 1985, playing a woman and her identical British half-sister–cousin. Moore watched herself every day, tracking the mistakes she had made. After three years on the soap, she won a Daytime Emmy for Outstanding Ingenue in a Drama Series. A few compelling projects came in the years following — The Hand That Rocks the Cradle, alongside Annabella Sciorra; a cameo in The Fugitive — but Moore’s career picked up real steam after she appeared in Robert Altman’s Short Cuts, her first turn as a villain you can’t help but root for. Her character clearly loves torturing her husband, and we love watching her do it, the glittering fireworks of rage that she sets off. “She knows not to judge characters, which is part of the pleasure of what we do,” says Annette Bening, who played Moore’s wife in 2010’s The Kids Are All Right. “She’s not overly earnest in her work. There’s always a little bit of a twinkle in the character.” In one scene of Short Cuts, Moore famously monologues with her pants off. She did it, she has said, because it was a realistic portrayal of a marriage. Life doesn’t always happen under good lighting — things happen when they happen.

By 1990, André Gregory had hired Moore, along with Wallace Shawn and Lynn Cohen, for a workshop of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya. It was a grand idiosyncratic experiment: The actors rehearsed the play for three years, mostly in the decrepit Victory Theater in Times Square, where they were given time to sink into the marrow of the text. There was no expectation that it would ever be seen by an audience. “In Chekhov, people are always talking about boredom, about how they don’t have anything to do and everything’s the same,” Moore, who played the beautiful and vapid Yelena, tells me. “And of course, looking at it now, we worked on it for so long that André actually allowed us to get bored. That experience of letting something seep into your skin — that’s where André excelled with us.” Gregory and the cast cherry-picked a few friends — Mike Nichols, Susan Sontag, Richard Avedon, Altman — to watch, but the production wasn’t widely viewed until it was filmed by Louis Malle and released in 1994 as Vanya on 42nd Street.

Gregory, now 89, calls me from his home in New York and remembers insisting on meeting with Moore after he saw her in Caryl Churchill’s Ice Cream With Hot Fudge at the Public Theater. In one scene, Moore had to be completely silent — and still, Gregory left the theater stunned by the emptiness of the moment. Over dinner later that night, she explained to him that she had simply been counting to 60 in her head. “She knows how to get extraordinary results in very unusual ways. She’s so extraordinarily beautiful, and she’s clearly a great actor — at the same time, what comes out of her is often quite dangerous,” he tells me, comparing her to Marilyn Monroe singing to JFK. “Not because she’s dealing with a scary character, but she has a wonderful savage quality.”

A run of decent films in the mid-’90s — Nine Months with Hugh Grant; Assassins; The Lost World: Jurassic Park, directed by Steven Spielberg — set her up for recognition. In 1995, People magazine named her one of the most beautiful people in the world. As her career took off, though, her personal life sputtered. By the end of that year, Moore had married and divorced actor and director John Gould Rubin. (A rare vintage moment of Moore’s claws: “I have one word for you: prenuptial,” she said in a 1997 interview with New Woman magazine. “I make commercial movies because I need to pay my alimony.”)

As time crept on, she realized she needed to stop waiting and start planning. Despite her professional success, “it became apparent to me at a certain point in my later 20s that I was not living the kind of life that I wanted to have personally,” Moore tells me over our pots of tea. In her 30s, she quit smoking and started therapy. A year after her divorce, she met Freundlich, who needled her into reading a part for his film. She was 35, he was 26, but it worked — even today, she calls him “the miracle of my life.” They had their first child, Cal, in 1997 and eventually got married in 2003.

“I don’t think I could be happy as an actor if I didn’t have a really fulfilling personal life,” she says. It’s easy to get lost in the tides of fame; you need an anchor. “That’s the great thing about having a real life and having a creative life: You can have both,” she continues. “I don’t like those narratives that say somehow you have to give up being a human being to be a creative person.”

By then, she had entered one of the golden eras of her career, doing work that was both weird and incredibly well received. In 1998, Moore was nominated for a Best Supporting Actress Academy Award as the maternal porn star Amber Waves in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights. As Amber, Moore endeared and titillated and confused. There’s a scene where she’s snorting coke with Rollergirl, motormouthing on about how much she misses her two sons, little Andrew and Dirk Diggler. That same year, Moore added another iconic outré character to her repertoire: avant-garde artist and Über-feminist Maude Lebowski in The Big Lebowski. From that point on, she was a bona fide star.

Moore has done her fair share of nudity in her career, but there are few other actresses her age — Juliette Binoche is one — who embrace not only nudity but sex: Moore’s characters have sex as much as they do any other human activity, which is to say pretty often. Even as she’s gotten older, her nudity is never used as a gimmick (Diane Keaton in Something’s Gotta Give) nor as a heavy-handed moment of empowerment (Emma Thompson in Good Luck to You, Leo Grande). She’s also not above rejecting it, as she did with 2007’s Savage Grace, a film about the tortured and occasionally incestuous relationship between Barbara Daly Baekeland and her son, convincing director Tom Kalin it wasn’t essential to the plot. Moore will do a sex scene only if it’s plausible in a story’s natural sway.

In the aughts, Moore’s career spidered out into all types of projects, from the prestige (The Hours, Magnolia, A Single Man) and the indie (The Kids Are All Right), to action-thrillers (Next, Children of Men) and rom-coms (Don Jon; Crazy, Stupid, Love). There are plenty of misfires in her filmography (Freedomland, The Ladies Man, The Woman in the Window), but because Moore is both prolific and good, the bad ones don’t stick to her. In 2015, on her fifth nomination, she won her first Academy Award, for Still Alice, in which she plays a Columbia University professor succumbing to early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Maybe the lucky way had worked: She had a healthy marriage, a happy family, the types of awards that are supposed to erase doubt. Plus it turned out — if the bros at Lebowski Fest are to be believed — people really liked her freckles.

In late January, Moore calls me from Madrid, where she’s rehearsing The Room Next Door, Pedro Almodóvar’s first full-length English-language film. “I can remember seeing Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and marveling at the filmmaking,” she says. “And here it is; I’m actually working with Pedro now. If I knew that then, I would be shocked.”

It’s a few days after this year’s Oscar nominations were announced, and May December, thought to sweep, received just a single nomination: Best Original Screenplay for Samy Burch. The snub was unexpected, to say the least. As if having a renowned director, two Oscar winners, and a young, largely unknown hunk displaying serious dramatic chops weren’t enough, it’s also a movie about making movies, which is usually Academy catnip. “You feel like, Oh, okay,” Moore says, her voice deflating. “We would all like to go to the party, but not everybody gets to go. That’s just how it is.”

Last summer, she had been planning to take a break when the SAG-AFTRA strike went into effect. She had just finished May December and had immediately started shooting Mary & George. She did all the normal stuff during her downtime — yoga, ceramics classes, family time at her house in Montauk. When the kids were young, she tried to build her schedule around them, taking projects that would keep her in New York, arranging her travel schedule so she was never away from them for more than a few days at a time, even taking them on location with her. (At 3 years old, her son could do a decent impression of Anthony Hopkins on the Florence set of Hannibal.) Her daughter is about to graduate from Northwestern; her son, a musician, is 26 and lives with his girlfriend in Manhattan. Now when Moore goes home, it’s just to Freundlich and Hope, their rescue dog. “She’s 60 percent pit, 10 percent shepherd, 10 percent Lab, and 20 percent Chow Chow,” she says, “which is a hundred percent gorgeous.”

I wonder how she will feel now that her house is a little quieter than it was in her 50s, now that she has more space and time to pretend, the way she did as a kid. When asked for a good way to understand Moore, Bening tells me about how much money she raised for other entertainment workers during the strike: “She sees herself in the community and what she can offer as being important — and not just financially, although she also steps up financially, too.” Since the mass shooting at Sandy Hook in 2012, Moore has campaigned for gun control, speaking at a rally in front of the Supreme Court in November and posting weekly “Woman Crush Wednesdays” about women in gun-violence prevention. As someone with kids in school, she found the issue became impossible for her to ignore. “I realized I wasn’t keeping my children safe if I didn’t do my part to change the legislation,” she said in an interview last year. “I thought, I’m not being the parent I want to be. I thought that if something happened to them, it would be my fault.”

Not all of Moore’s big swings have made contact. Recent projects The Glorias and Dear Evan Hansen haven’t earned the same sort of critical attention she found earlier in her career, though — based off its first few episodes — Mary & George may change that pretty soon, as might Stone Mattress, a film based on a Margaret Atwood short story, co-starring Sandra Oh. “People sometimes are under the impression that we just have this avalanche of scripts that we go through; it’s not always the case,” Moore says over lunch. At times, there’s just not a lot of stuff being made or a dearth of roles you’d be good for. May December is her best film work in years, showing how good she — still! — really is.

My favorite recent film of hers is 2018’s subtle and intimate Gloria Bell, a remake of the 2013 Chilean film Gloria, in which she plays the title character. It is a divorce movie about the benefits of divorce: Instead of feeling lonely, Gloria is buoyant and brave, a sunbeam of a woman who spends much of the film under the disco ball. That’s where she meets Arnold (John Turturro), who romances her before one of them goes and screws it all up. It’s a sultry movie, all mood lighting and Moore in huge, sexy-secretary glasses. Gloria and Arnold don’t have the kind of coy sex where they hide their bodies under bedsheets. It’s so honest, too: I can still hear Turturro ripping off his gastric belt before they fall into bed together. That rip is the sound of putting yourself back out there, surfing whatever wave comes your way.

A single mention of the movie during our lunch broke me open. Gloria Bell is a film about a woman being honest with herself, striding toward who she’s meant to be. Suddenly, I wanted to confess everything to the woman who embodied this character: my petty anxieties and my small failures, the new narratives I was constructing about who I was. I just felt like Moore would get it.

More From the spring 2024 fashion issue

- Bring Back These ’00s Trends

- Packing for Paris With Alex Consani

- Where New York City Tweens Actually Like to Shop