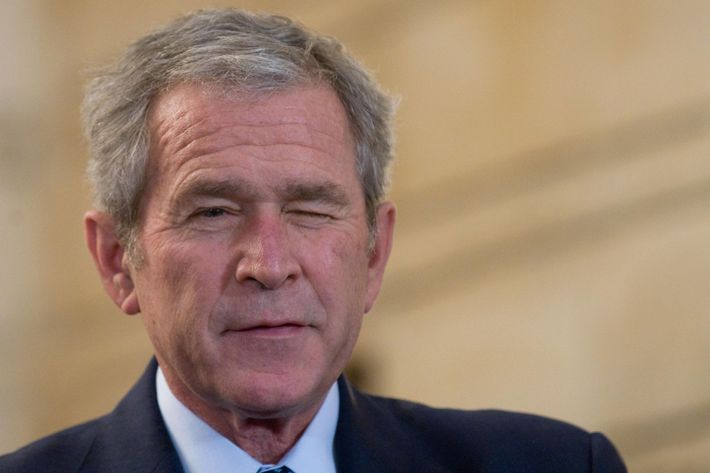

If you’re a famous person who wants to make some headlines, winking seems like a pretty low-effort, high-payoff way to do it. Sarah Palin did it during the 2008 vice-presidential debates. George W. Bush did it to Queen Elizabeth II in 2007. People went nuts for Olympic gymnast Laurie Hernandez’s wink to the judges in Rio. Australian prime minister Tony Abbott’s infamous wink during a 2014 radio show went, um, very differently. And then there’s this.

The lesson in all these examples: Once the wink is out there, it’s anyone’s guess as to how the public will receive it. Which is kind of a perfect parallel to what little psychologists do know about it – namely, that it’s one of the most wide-ranging, ambiguous behaviors there is. A wink can be friendly, conspiratorial, flirtatious, lecherous, sinister … you name it, really. (For that matter, so can the ever-mysterious wink emoji.)

To be fair, it’s true that other facial expressions can be ambiguous: “A smile can indicate happiness, derision, or even pain. A furrowed brow can communicate anger, confusion, or concentration,” psychologist Lisa Williams wrote last year in a column on the Conversation. “In all these cases, especially emotional ones, perceivers look to context to figure out the meaning.” But the difference may be that we’re more practiced at figuring out the context for those other things. They’re more necessary — a smile’s typically the easiest, most efficient way to communicate happiness. Ditto a furrowed brow for confusion.

A wink, on the other hand, is not the go-to way to communicate anything in particular. It’s superfluous. It’s intentional. It’s less natural, and therefore harder to parse. Robert Provine, a psychology professor at the University of Maryland and the author of Curious Behavior: Yawning, Laughing, Hiccupping, and Beyond, describes winking as a distortion of a more natural behavior: “The blinking eyelids are the [body’s] windshield wipers,” he wrote in an email. “Winking involves the hijacking of the biological maintenance behavior of blinking in the service of social signaling.” Here’s what we know about that signaling — and what we don’t.

It’s like handedness — you’re a righty or a lefty for winking, too.

Though our bodies may look symmetrical, that’s not the case below the surface. We write with one hand; we tend to kick with one foot; whenever you do a half-smile, chances are you always lift the same corner of your mouth.

The same thing’s true of eyes — we tend to favor one over the other, a phenomenon called ocular dominance. Imagine for a second that you’re looking through a telescope, or the viewfinder of a camera — which eye are you using? That’s your dominant eye, the one your brain relies on more heavily for visual information. Odds are, the other one — the non-dominant eye — is the one than feels more natural to wink.

But some people really can’t do it at all.

Here seems like a good place to define the terms: A wink, or one-eyed blink, happens when you contract a facial muscle called the orbicularis oculi, which controls eyelid movement. Like all movements of the face, the motion is managed by the facial motor nucleus, a group of neurons in the brain stem that help you do everything from smiling to furrowing your brow. Within the nucleus, different subgroups of neurons control different muscles, with more activity focused on the lower half of the face — the reason why contorting your mouth a certain way feels easier than doing the same to your eyebrows.

This setup also why why some people, no matter how hard they try, just can’t wink: The muscles that winking requires just don’t have the real estate in the facial motor nucleus (a recent Very Important Internet Investigation has concluded that Rihanna is likely on one of those people). The connection between the brain and the muscles isn’t strong enough — not a cause for concern, healthwise, but kind of a pain if you’re trying to be smooth. At least Rihanna’s in good company.

Even in the digital world — especially in the digital world — a wink can be ambiguous.

Here’s a challenge for your fresh-start September: Instead of carbs or caffeine or toxic friendships or whatever, try cutting out the winky emoji. At best, it comes off a smidge passive-aggressive; at worst, it can up the odds that whatever you’re trying to say will be misinterpreted.

Confirming what most people with two thumbs and a phone already knew, one 2015 study in the Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology found that a wink makes a message seem more sarcastic, even when that’s not the intention. Study participants read Facebook and text conversations with and without emoticons —some written to be sincere, others to be sarcastic — and tried to describe the intent behind the messages. When the messages were more ambiguous, meaning the participants didn’t have enough context to tell whether the sender was being sincere, the addition of a winky face reliably pushed it into sarcastic territory. It also enhanced the emotional effect of whatever was being said: A candy-coated barb like “I loved your outfit ;)” was perceived as more negative when it came with a wink, while a sarcastically delivered compliment like “Ugh, you looked terrible ;)” was more positive.

But other studies have come up with conflicting results — some argue that emoji don’t actually do much to convey sarcasm, or that punctuation is more effective. Anyway, real life doesn’t really adhere to the research premise. It’d be one thing if everyone agreed to only use wink emoji for sarcasm and nothing else. But people pepper their digital conversations with wink faces for all kinds of reasons beyond sarcasm, rendering them useless as tools of clarification. Anecdotally, I’ve helped enough friends analyze their Tinder conversations to argue that the winky face can also signify a sort of eager desperation, like the typographical equivalent of laughing too loudly at something that wasn’t actually a joke (though, to the best of my knowledge, there’s no research yet that backs that up — just a trove of awkward exchanges).

You can’t really control how your wink is interpreted.

As a matter of fact, there’s not much out there in the way of winking research, period. The most widely cited study that I could find on the subject — a paper published in 2009 in the journal Communication Research Reports — showed just how wide-ranging the gesture can be. In the study, male and female actors stationed themselves at a college campus and a shopping mall and approached passersby to ask for the time; once the other person responded, the actor thanked them, winked, and walked away. Immediately afterward, a researcher would appear to ask the person if they’d noticed the wink, and if so, what they’d thought of it: Where did it fall on a scale from normal to weird? Did it make them uncomfortable? Did it leave a positive or negative impression? How friendly, polite, attractive did they find the winker? And lastly, what did they think the wink was supposed to mean?

The most popular interpretations: The wink was meant as a way of communicating thanks, or it was a sign of friendliness, or it was a flirting move. Other theories lower down on the totem pole included the possibility that the winker had an eye problem, was trying to seem cool, or was expressing some strange ulterior motive — they “didn’t really want to know the time,” one person offered.

So we know this much: The exact same eye movement, from the exact same person, can seem like any number of different things. In some cases, the study authors wrote, winking is seen as an “involvement behavior” — something that helps build rapport between two people, like leaning toward someone or making eye contact with them. In others, it’s interpreted as a “reinforcement behavior,” underscoring some other piece of the social interaction — like using it to show thanks, even if you’ve already expressed the same sentiment verbally.

And that uncertainty is why winking can be creepy.

In some cases, a wink is interpreted as something more repellent: The same ambiguity that surrounds winking is also the defining feature of creepiness. We consider someone creepy when their weird behavior makes them seem unpredictable, which, by extension, makes it harder to determine whether or not they actually constitute a threat. So it is with winking: If you and a friend are poking subtle fun at someone who has no clue they’re being made fun of, for example, it’s fairly easy to see that friend’s wink as, “Hey, we’re the only ones who’re in on this joke.” But if a stranger on the subway does it, you don’t have the same situational knowledge base through which to interpret the gesture, which is why winks can so easily go awry.

And why the flirtatious ones, in particular, are a high-risk move (especially considering the fact that we’re pretty bad at knowing when someone’s flirting with us). A 1996 New York Times story on a flirting class described the objectives this way: Participants learned, among other things, “the differences between a flirtatious glance and an uncomfortable stare,” “where and when flirtation is appropriate,” and “when and where not to wink.”

One student offered up this as her main takeaway: “At least now I know that a wink isn’t just a wink.” What it is, though, is anyone’s guess.