When I Was Young and Uneasy

From her autobiography, TAKEN CARE OF, which DAME EDITH SITWELLfinished shortly before her death,we have drawn these passages,which disclose some of the angularities of her girlhood and the solace which she early found in poetry. Her volume of reminiscences will be published by Atheneum in April.

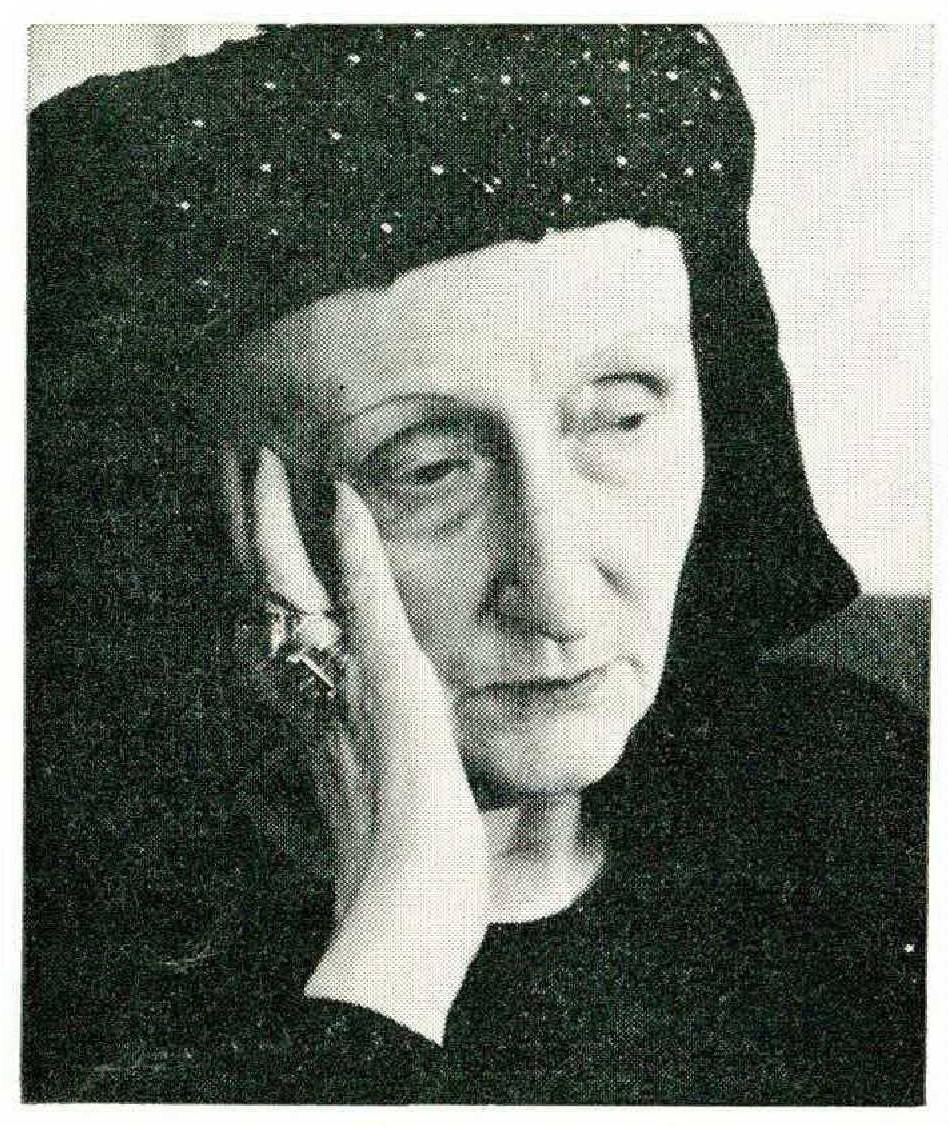

Dame EDITH SITWELL

I WAS unpopular with my parents from the moment of my birth, and throughout my childhood and youth. I was in disgrace for being a female, and worse, as I grew older it was obvious that I was not going to conform to my father’s standard of feminine beauty. I in no way resembled a Pekingese, or one of those bloated pink imitation roses that my father (who had never forgiven himself for marrying a lady) admired. Instead, I had inherited the Plantagenet features and deep-set eyes of my grandmother Londesborough.

I was a disappointment. My eighteen-year-old mother had thought she was being endowed with a new doll — one that would open and shut its eyes at her bidding, and say “Papa,” “Mama.” I was unsatisfactory in those ways, as in every other, I must have been a most exasperating child, living with violence each moment of my day. I was rather a fat little girl: my moon-round face, which was surrounded by green-gold curls, had, strangely for so small a child — indeed, for any child — the eyes of someone who had witnessed and foretold all the tragedy of the world. Perhaps I, at four years old, knew the incipient anguish of the poet I was to become.

My father had only one comfort. In my earliest childhood, before he had retired into a Trappist seclusion within himself, he had seen himself always as the apex of one of those hierarchical family pyramids favored by photographers. Then, when I was just able to walk, he saw this imaginary photograph labeled “Charming photograph of a young father with his child.” And under the spell of this fantasy, he would bowl me over with a cushion, pinning my forehead to the iron fender.

I was an embarrassing child. There was an occasion when Davis, our nurserymaid, was asked to bring me down to the drawing room at Wood End to see one of Mother’s friends, a delightful young woman with a summery appearance. She was thin-waisted like a Minoan bee-priestess. She cast a shadow like a long bird’s. It seemed as if it must be singing, and had nothing to do with the darkness of grief. Some years after this time, worn out by poverty and a hopeless love affair, she killed herself.

“You remember me, little E?” she inquired when I was brought into the room. (For some reason, I was always addressed by this one letter, until my brother Osbert, at that time unborn, was able to speak. Then I was called “Dish,” as it was impossible for his baby tongue to pronounce “Edith.”)

“Don’t you remember me?”

“No.”

“Children have the most unreliable memory,” said my father, blinking.

“What are you going to be when you are grown up, little E?” asked Rita, a warmhearted creature who wished to avert from me my parents’ wrath.

“A genius,” I replied.

I was promptly removed from the drawing room and put to bed. But my disgrace was not forgotten, and was frequently referred to in after years in a disgusted whisper.

MY FIRST real adventure, outside of those which even then illuminated my mind, was my visit to Cannes when I was four years old. Of the sea journey I remember only the elephantlike trumpeting of the sirens, and my incessant shrieks because the ship, with unaccountable obstinacy, continued its course without asking my permission.

The train journey was fraught with danger. My mother occupied the lower berth of our sleeping compartment, while Davis and I, by means of a very rickety ladder, climbed to the upper berth. I was suffering from a sty on one of my eyes, and howled most dismally. My mother, never slow to wrath (and certainly on this occasion she deserved every sympathy), threatened to throw me out the window. This project, throughout my early childhood, was her method of inducing affection.

I howled, of course, even more loudly.

I was not thrown out, otherwise this record would never have been written; and Davis soothed my mother by making tea in an upper berth, endangering, by means of a flaring spirit lamp and spluttering matches, the train, ourselves, and our fellow travelers.

However, in spite of these dangers, we arrived, to find ourselves in a world where flowers reigned, with their scent like a soul, in great fields of narcissus that seemed white shadows cast by the snowcovered mountains above them, and fields of yellow jonquils that in my later life were like the spirits of my early poetry:

flamme dans les cheveux tristes du pauvre Songe.

Aux plus claires chevelures, fleurs trépassèes,

feurs de janis.

So wrote poor Remy de Gourmont, seeing that beauty in spite of the tragic disease that had partially destroyed his face. And that lovely passage remains with me like a memory, of those fields in which I walked as a little child (although there were, in that springtime, no soucis dorés, no marigolds).

One day, in those fields, as Davis and I were standing under the pale green light, that was like water flowing, of a eucalyptus tree, she said to me, “Her carriage is coming. You must curtsy.”

The barouche contained an old lady in widow’s weeds. I curtsied, and received an impressive bow. The old lady was Queen Victoria. I was curtsying to an age, a world, that was passing.

On our return to Renishaw, I concentrated my love on the Renishaw peacock.

This love was, at the time, returned.

When we were at Renishaw, punctually at nine o’clock every morning (it is strange how birds and animals have an accurate sense of time) the peacock would stand on leads outside my mother’s bedroom, waiting for me to come and say good morning to her. When he saw me, he would utter a harsh shriek of welcome. (I do not, as a rule, appreciate ugly voices, but I loved him so much that nothing about him could be wrong in my opinion.) He would wait for me until I left my mother’s room, then, with another harsh shriek, would fly down into the large gardens. We walked around these, with my arm around his lovely neck that shone like tears in a dark forest. If it had not been for his crown, we should have been of the same height. Davis said to me, “Why do you love Peaky so much?”

I said, “Because he is beautiful and wears a Heavenly Crown.”

(“The pride of the peacock,” said William Blake, “is the glory of God.”)

This romance lasted for months. Then my father bought Peaky a wife (in my eyes a most dull and insignificant bird), and Peaky discarded my companionship and devoted himself entirely to teaching his children to unfurl the tails with which they had been endowed as fans.

I do not think it was the injury to my pride at being jilted by a peacock that I minded. It was the injury to my affection. It was my first experience of faithlessness. My other friends at this time were a puffin with a wooden leg (his real leg had been injured in an accident: he was like an old sea captain from some book by Dickens), and a baby owl that had fallen out of its nest, which used to sleep with its head on my shoulder, pretending to snore in order to attract mice. But until the birth of Osbert, when I was five years old, my only human friends, apart from Davis, Henry Moat, and my cousin Veronica, daughter of my aunt Lady Sybil Codrington, were Mollie and Gladys Hume, the daughters of a Colonel Hume, a tall, storklike personage who resembled a character in Struwwelpeter (one imagined him, always, as carrying a gun, stalking, over green baize grass against a background of large leaves of the same color and texture, a fleeing hare; or like a character in Stravinsky’s Chansons Plaisantes. Both these works influenced, very greatly, my early poetry).

Colonel Hume was the original of “Old Sir Faulk” in my “Fox Trot” as far as his physique was concerned. But I placed him in the countryside of our dear old friend and neighbor Colonel Chandos-Pole, at Radburne.

The Hume children were about the same age as myself, four or five. One afternoon, after I had not seen them for some time, Davis and I went to tea with them. They seemed little shadowed beings, dressed in black.

Their mother was generally present at nursery tea, but on this occasion she was not there, and I asked where she was. They cried bitterly. “She is dead,” they said. Soon afterward, we left, not staying for the usual after-teatime games. I asked Davis why they had cried.

“Because their mother is dead.”

“Yes, I know. But why did they cry?”

I LEARNED to read before I was four years old, my reading then consisting of the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm and Hans Andersen. Many stories of the latter frightened me, as I could not bear the loneliness that seemed to pervade them. I shrank from the coldness of the Snow Queen. Now my life is warm, but when I was a child, I was ineffably cold and lonely. So much so that I ran away from home when I was five years old (I do not know to what I was escaping), but as I could not do up my buttoned boots and had no money, I was captured by a young policeman and restored to my parents. At that time Osbert had been born, but that warm heart that has never failed anyone could not, as he was only a few weeks old, find speech to express itself.

But there was another, ugly, commonplace world to be faced. My friend the baby owl had to snore in order to attract the attention of mice. Throughout my life, I have been so unfortunate as to attract mice (of the human species) without the effort of snoring.

By the time I was eleven years old, I had been taught that Nature, far from abhorring a Vacuum, positively adores it. At about that time, I was subjected in the schoolroom to a devoted, loving, peering, inquisitive, interfering, stultifying, middleclass suffocation, on the chance that I would become “just like everybody else.” For as Herr Bernhardt Rust, Reichminister of Culture and Education, stated in Education and Instruction, “No individual must think himself more brilliant than his fellows: we must have no intellectuals. Each mind is of equal importance.”

Minds must, in short, be ground down until there is nothing left but flatness. Trotsky said in Problems of Life, “It is well to have life ground by the grinders of proletarian thought. The grinders are strong, and will master anything they are given to grind.”

The middle-class grinders to which I was as a child subjected in the schoolroom and the grinders of upper-class mentality to which I was given over when a very young woman have been attempting to subdue me throughout my life. They have never mastered me. The idea that I could be mastered by anyone or anything (of course my loving tormentors, in their proud edifices of cotton wool, have never been, even vaguely, in touch with proletarian thought) was simply the effect of wishful thinking.

In the midst of the suffocation to which I have referred, my parents noticed that I stooped slightly, owing to curvature of the spine, and that my very thin ankles were weak. I was therefore handed over, lock, stock, and barrel, to an orthopedic surgeon in London, Mr. Stout. This gentleman’s life consisted in one long campaign against the human frame. He decided immediately that I was all wrong from A to Z, and that my muscles must be atrophied as far as possible.

I remember little of Mr. Stout’s outward appearance, excepting that he looked like a statuette constructed of margarine, then frozen so stiff that no warmth, either from the outer world or human feeling, could begin to melt it. The statuette was then swaddled in padded wool, to give an impression of burliness.

After my first interview with Mr. Stout, I was trundled off to an orthopedic manufacturer and incarcerated in a sort of Bastille of steel. This imprisonment began under my arms, preventing me from resting them on my sides. My legs were also imprisoned down to my ankles, and at nighttime these and the soles of my feet were locked up in an excruciating contraption. Even my nose did not escape this gentleman’s efficiency, and a band of elastic surrounded my forehead, from which two pieces of steel (regulated by a lock-andkey system) descended on each side of the organ in question, with thick upholstered pads at the nostrils, turning my nose very firmly to the opposite way from what Nature had intended, and blocking one nostril, so that breathing was difficult. This latter adornment, however, was worn only during my long hours in the schoolroom, as it was thought that it might arouse some speculation — even, perhaps, indignation — in passersby if worn in the outer world.

I mention this Bastille existence of my childhood only because it throws a light on my later life, having semiatrophied the muscles of my back and legs. For some reason, my hands and arms remained in freedom, so that I am able to move these with, I might even say, fluidity of motion, expressiveness.

The manufacturer of my Bastille, Mr. Steinberg, was an immensely fat gentleman, who seemed to spread over London like a fog. This impression was enhanced by the fact that he was fog-yellow. His eyes, and all the expression that they may have held, were shrouded behind black glasses. Long after my childhood was over, I came face to face once again with those black and airless dummy windows, in an omnibus in Bayswater, and felt again the sickened fright, humiliation, and sense of hopeless imprisonment I had known as a child.

MY PARENTS were surrounded, for the most part, by semianimate persons like an unpleasant form of vegetation, or like dolls confected out of cheap satin, with here and there buttons fastened on their faces in imitation of eyes.

My mother was slightly too insistent on her social position. (Those were the days when an earl was regarded as a being on the highest mountain peaks, to be venerated, but not approached, by ordinary mortals.) She was in the habit of saying, no doubt with my father in mind, “A baronet is the lowest thing on God’s earth” — lower, presumably, than a black beetle. And when she was in a rage with me — this being a constant state with her — she would say to me, “I am better born than you are.” This puzzled me slightly.

But my mother’s insistence on her social position did not prevent her from making close friends with persons who could not possibly have found their way into Lady Londesborough’s drawing room. One of the worst of these subhumans was Miss Diana Pilkington, an alleged beauty. She was a person who seemed to have been divided exactly in two. The upper part of her body consisted of an enormous pink ham which served her as face. The lower half was like one of those legless toys which rock from side to side if given a slight push. She was a thick, dulled creature behind that great inexpressive pink facade, which had blunt, unformed features affixed to it simply because she had to have a mouth with which to eat and a nose with which to smell out the miseries of others.

The occupation of trying to attract admiration filled up, for the most part, her days, although her coarse pink fingers, that looked as if someone had cut them off, like meat, at the first joints, would sometimes indulge in “ribbon work” — sewing imitation pink and scarlet Dorothy Perkins roses of bunched ribbons on to obstreperously shiny white satin (needlework which had recently been imitated from one of the more stupid eighteenthcentury minor painters). Though she was of completely contemporary human origin, she yet aroused in me the conjecture that the Almighty had been trying on her His prentice hand.

She had a shocking influence on my mother, who seemed to be entirely hypnotized by her commonness. (My mother, at that time, had but few companions. They came, but either the wind from the North Sea or some aimless, dull, spiritual wind blew them away again.) On a few occasions, Miss Pilkington induced my mother to accompany her on a midnight rat hunt in the cellars of a large hotel in Scarborough. This was Miss Pilkington’s preferred sport. But it was a strange behavior for a woman of my mother’s breeding and fastidious cleanliness. She was, as I have said, hypnotized. Ratcatchers, terriers, and large sticks would be collected, and Miss Pilkington would join the ratcatchers in knocking the squealing creatures on the head and encouraging the terriers to worry their throats. Spattered with rat’s blood, “the best fun in the world,” she would say.

Diana Pilkington enjoyed watching suffering. It was an especial joy to her to intrude into my schoolroom in order to feast herself on the humiliation I suffered in my Bastille of steel. Often she would bring with her persons of an equal breeding, complete strangers to me, and they would laugh openly and delightedly at my helpless state. My grandmother Londesborough was kept in ignorance of the existence of this dreadful woman and “the best fun in the world.”

Every Saturday afternoon, I was “kept in” as a punishment, because I either could not or would not learn by heart “The boy stood on the burning deck,” the boy in question being, in my childish eyes, the epitome of idiocy, because, as everybody else had left the burning deck and he was doing no conceivable good by remaining there, why in heck didn’t he get off it! I was unwilling, therefore, to pay lip service to this idiotic episode. This refusal, on my part, was recurrent when I was between the ages of eleven and thirteen.

On the other hand, I knew the whole of Pope’s The Rape of the Lock — the only poem of genius to be found at Wood End — before I was thirteen, having learned it secretly at night when my governess was at dinner, sitting up in bed, bending over it, poring over it.

From the thin, glittering, occasionally shadowed, airy, ever-varying texture of that miracle of poetry, the instinct was instilled into me that not only structure but also texture is a parent of rhythm in poetry, and that variations in speed are the result not only of structure but also of texture.

I was to learn in after life that the ineffably subtle and exquisite changes in the following lines, for instance, from a passage about the Sylphs:

Waft on the Breeze, or sink in Clouds of Gold;

Transparent Forms, too fine for mortal sight,

Their fluid Bodies half dissolv’d in Light.

Loose to the Wind their airy Garments flew,

Thin, glitt’ring Textures of the filmy Dew;

Dipp’d in the richest Tincture of the Skies,

Where Light disports in ever-mingling Dyes,

While ev’ry Beam new transient Colours flings,

Colours that change whene’er they wave their Wings

are caused by particular arrangements of onesyllabled and two-syllabled words with others that have the slightest possible fraction of an extra syllable, casting a tiny shadow, or, when placed close together, producing a faint stretching pause — as with “their airy” (here, of course, the fact that these words are assonances adds to the effect). The changes in the movement are caused, also, by softening assonances, such as “some,” “sun,” placed in a certain arrangement with assonances that change from softness to poignancy — “InsectWings,” “Thin glitt’ring.” The poignancy of the “g” in “Wings” lengthens the line very slightly. The changes in the movement are caused, also, by an incredibly subtle and ever-varying arrangement of alliteration and of vowel schemes, these latter stretching the line, making it wave in the air, heightening it or letting it sink. But in discussing this, of course, I speak as a practiced poet, not as the child in whom this knowledge began as instinct.

I do not intend to write more about my schoolroom days. I learned from the world, not from maps. And all living beings, human, animal, or plant, were my brothers. To me, as a child, glory was everywhere, and what visited me then in my sleep visits my working world now that I am a woman.

Ever since my earliest childhood, seeing the immense design of the world, one image of wonder mirrored by another image of wonder — the pattern of fur and feather by the frost on the windowpane, the six rays of the snowflake mirrored in the rock crystal’s six-rayed eternity — seeing the pattern on the scaly legs of birds mirrored in the pattern of knotgrass, I asked myself, were those shapes molded by blindness? These were the patterns used by me, consciously or unconsciously, in certain of my early poems, “Bucolic Comedies.”

In many of my early poems the subject is the growth of consciousness. Sometimes it is like that of a person who has always been blind and who, suddenly endowed with sight, must learn to see; or it is the cry of that waiting, watching world, where everything we see is a symbol of something beyond, to the consciousness that is yet buried in this earth sleep.

The poem “Aubade” in its present state (having passed through my own life, my own experience) is about a country girl, a servant on a farm, plain, neglected, and unhappy, with a bucolic stupidity, coming down in the dawn to light the fire.

The reason I said “The morning light creaks” is this: After rain, the early light seems as if it does not run quite smoothly. Also, it has a quality of great hardness and appears to present a physical obstacle to the shadows, and this gives one the impression of a creaking sound because it is at once hard and uncertain.

Of rain creaks, hardened by the light.

Sounding like an overtone

From some lonely world unknown

At dawn, long raindrops hanging from boughs seem transformed by the light, have the dull, blunt, tasteless quality of wood; though the sound is unheard in reality, it has the quality of an overtone from some unknown and mysterious world.

The lines

Will never harden into sight,

Will never penetrate your brain

With overtones like the blunt rain . . .

mean that to this girl, leaving her bed at dawn, the light is an empty thing which conveys nothing. It cannot bring her sight, because she is not capable of seeing.

Flames as staring, red and white

As carrots or as turnips, shining

Where the cold dawn light lies whining.1

To me, the shivering movement of a certain cold dawn light upon the floor suggests a kind of high animal whining or whimpering, a half-frightened and subservient urge to something outside our consciousness.

The poet must necessarily occupy himself, through all his life, in examining the meaning of material phenomena, and attempting to see what they reveal of the spiritual world. So I lived in my green world of growth, companioned by the animals and the plants.

That great mystic and philosopher Lorenz Oken wrote: “As the animal contains all elements in itself, so also it contains the plant, and is therefore both vegetable and animal kingdom, on the whole solar system. . . . Animals are entire heavenly bodies, satellites or moons, which circulate independently about the earth; all plants, on the contrary, taken together, are only equivalent to one heavenly body. An animal is an infinity of plants.”

This was how I saw the world as a child, as I see it now, when I am allowed to see anything, for I am positively hagridden. Because I am a poet, it is assumed that I must wish to pass my life listening to conversations strayed from Mrs. Dale’s Diary. Oddly enough, I do not. When I can escape from such excitements, I remember how Harvey — I quote this from A. J. Snow’s Matter and Gravity in Newton’s Philosophy —“thought that the heat in animals, which is not fire, and does not take its origin from fire, derives its origin from the solar ray.” And I feel, humbly, that even my blood must derive from that ray.

THE days at Scarborough were like the scales played by a child upon the piano, or raindrops running down the windowpanes.

“Sir George Beaumont,” wrote Coleridge, in Anima Poetae, “found great advantage through learning to draw from Nature through gauze spectacles.”

This, of course, is the mark of the amateur, who invariably blurs and softens. Nothing could have been less amateur than my brothers and myself. We were born to be professionals. But my father’s hope was that I should learn to draw, to see everything, through gauze spectacles. Nothing must have sharp edges; the truth must be comfortably veiled. He wished my brothers and me to be equally semiadept at everything, and passion for the object seen, or heard, must be rigidly excluded. The less gift we had for anything, the more we were forced to practice it. Games, for instance, we disliked, and were, therefore, made to waste our time on them. Nor were they even supposed to be a recreation, but a means of “keeping up with the Joneses.”

Having discovered that I had no talent whatsoever for the pictorial arts, he determined that I should be forced to learn to draw at the local art school, which specialized in a damping-down process of an extraordinary proficiency. Michelangelo and Leonardo could emerge living from this tuition, but I doubt if any lesser painter could have survived it.

The drawing mistress was a kind, woolly, teaaddicted elderly maiden, Miss Alberts, who was always garbed in green serge (this being, I think, a tribute to Punch’s notion of the Pre-Raphaelites). She seemed to have been endowed with a treble ration of shining protuberant teeth, and these were always bared ingratiatingly. She did not hate art, she simply ignored it, excepting manually. And her right hand, which seemed to have a life, or rather death, of its own, was completely unconnected with her brain. This disconnected hand of hers guided my still fairly infantile hand to perpetrate a drawing of a plaster cast of a lion, of all subjects. The result may be imagined. Had I been forced to copy a plaster cast of a mouse, the passion of indignation, of injured pride — my pride and the fiery pride of the lion — would have been less. This ineffable drawing still exists and is referred to as “Dame Edith’s Lion”—the lion, I suppose, of the author of “Heart and Mind.”

Long ago, many years ago ... I remember staying with my grandmother Sitwell at Bath.

The delicate leafless cold seemed about to bud into those flowers, the first young flakes of snow. Old ladies in bath chairs were being whirled around and around the Roman moon-colored crescents, were being whirled around and around by bath-chair men who behaved as if they were typhoons; while, behind them, their captive women tugged at the old ladies’ bath chairs as if the old ladies were kites, and might at any moment fly over the houses, away and away.

Outside a stuffy bookshop, two maiden ladies were on the pavement lost in speculation. The elder of these wore a long dress which burst into a thousand leaves and waterfalls and branches and minor worries. She had hair of the costliest gold thread, bright as the gold in a fourteenth-century missal, and this, when undone, fell in a waterfall till it nearly reached her feet. But at this moment, it was crammed beneath a hat which seemed to have been decorated with all the exports of our colonies — ostrich feathers, fruits, furs, and heaven knows what besides. Her eyes were blue as a saint’s eyes, and were mild as a spring wind.

The younger maiden lady, then aged about eighteen, had the remote elegance and distinction of a very tall bird. Indeed, her gown had the feathery quality of a bird’s raiment, and one would not have been surprised at any moment if she had preened her quills. She stood there, in the delicate leafless cold, with her long, thin legs poised upon the wet pavement, as some great bird stands in a pool. She had not the look of one who has many acquaintances — not more, perhaps, than a few leafless flowering boughs and blackthorn boughs, and the early and remote flakes of the snow. Her only neighbor was the silence, and her voice had more the sound of a woodwind instrument than of a human voice. She was plain and knew it.

“An eighteenth-century memoir, Edith,” the older lady was saying, “is what your grannie would like — giving the life of the times.”

“Give me, if you please,” she said shyly, as she entered the shop, “some eighteenth-century memoirs,” and retired with the works of Casanova. Memoirs indeed, but the life of the times, eventually, failed to please the eldest lady for whom the life was intended.

“And I should like, if you please,” said the youngest lady, “some poems of Swinburne. Have you — ?”

“Oh, no. Miss,” said the shopman, flustered and shocked, “we have nothing of that kind. But should you care for the works of Laurence Hope, which are also full of love interest — ” The youngest lady did not think she would care for these, and, aunt and niece, they floated out again.

It is not too cold, said Miss Florence Sitwell, hopefully, for a little drive. And stepping into an unusually sprightly-looking, if ghostly, victoria, they went for a little drive in the dream country.

These places were among the green landscapes of my very early youth, landscapes scattered with “des plantations prodigieuses oÙ les gentilshommes sauvages chassent leurs chroniques sous la lumière qu’on a crééd.”

In these countrysides, the people know that Destiny is reported, and has feathers like a hen. There I have seen pig-snouted darkness grunting and rooting in the hovels. The very clouds are like crazy creaking wooden chalets filled with emptiness, and the leaves have an animal fleshiness. And here, beneath the hairy and bestial skies of winter, the country gentlemen are rooted in the mold; and they know that beyond the hairy and bestial aspects of the sky (that harsh and goatish tent) somethinghides; but they have forgotten what it is. So they wander, aiming with their guns at mocking feathered creatures that have learned the wonder and secret of movement, beneath clouds that are so low-hung that they seem nothing but wooden potting sheds for the no-longing disastrous stars (they will win the prize at the local flower show). The waters of the shallow lake gurgle like a stoat, murderously; the little unfledged feathers of the foam have forgotten how to fly, and the country gentlemen wander, hunting for something, hunting.

Now it was time to return to the house in the moon-colored crescent.

- Reprinted from COLLECTED POEMS, by courtesy of Vanguard Press; copyright © 1954, by Edith Sitwell.↩