What happened to United Colors of Benetton? How Zara, H&M and Uniqlo stole its thunder

- Its controversial advertisements once placed Benetton on the cutting edge of culture but by the early ’00s the Italian brand seemed unsure of who its market was

- While tastes in fashion changed, Benetton did not, and a relaunch of ’90s ad campaigns ironically came too early for this year’s wave of ’90s nostalgia

Benetton’s advertising campaigns were designed to be unforgettable. Somewhat ironically, 30 years on, they are the only thing many of us remember about a brand that was once hugely successful.

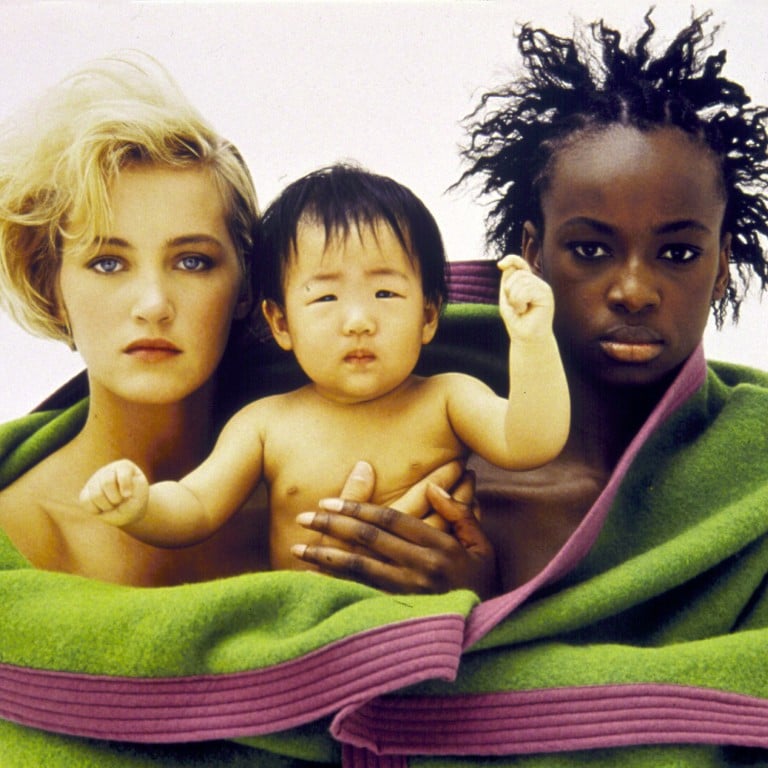

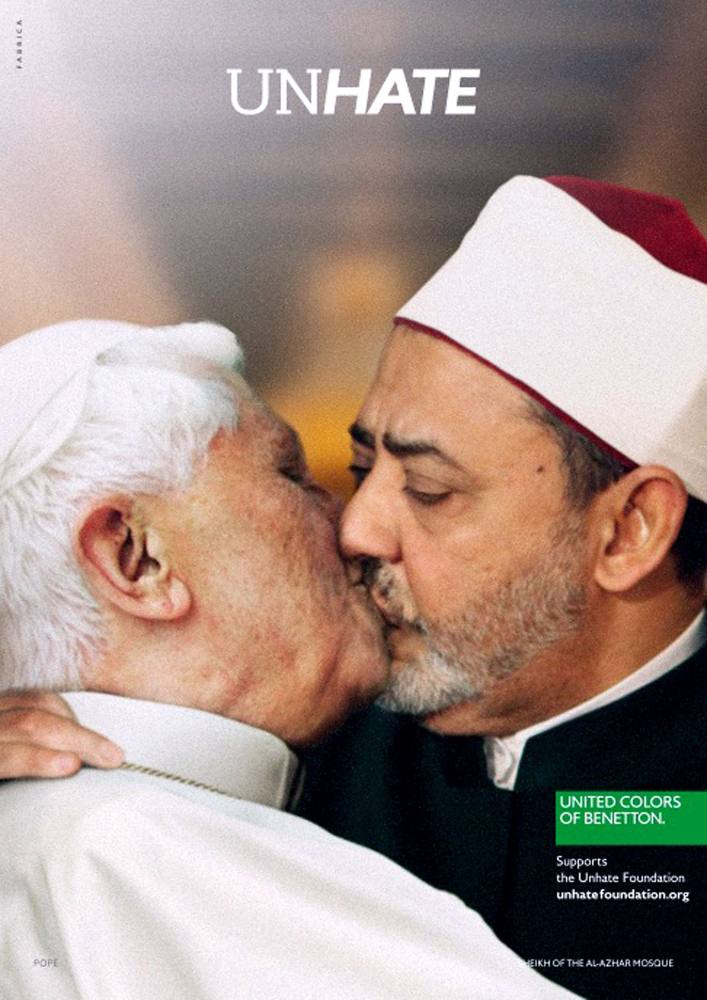

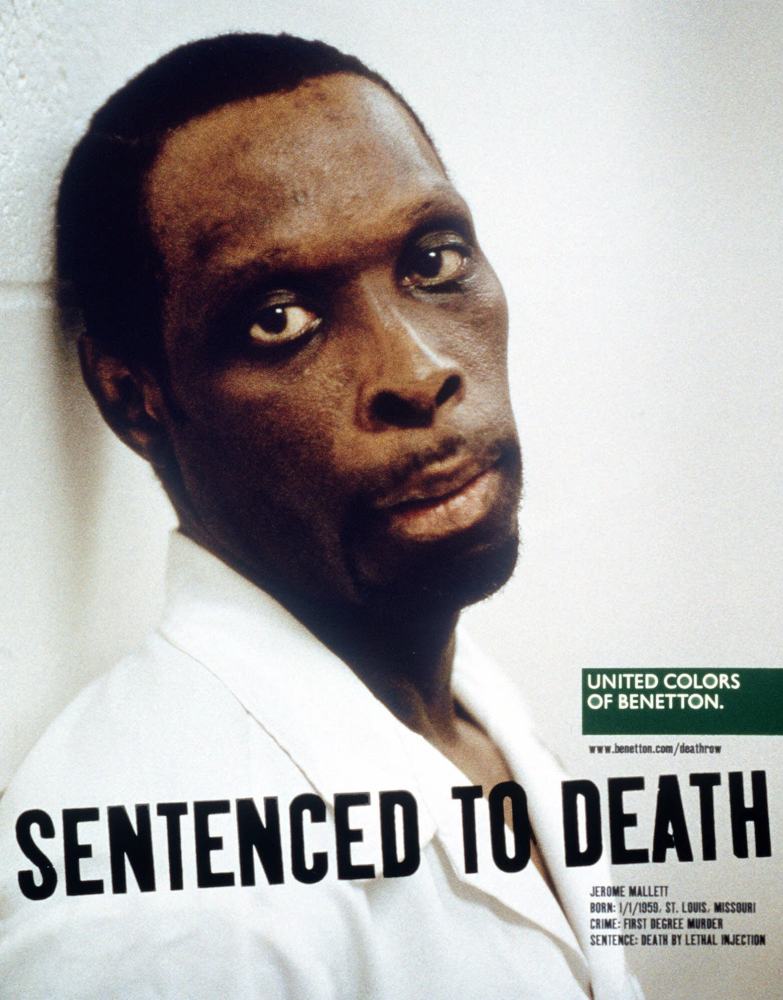

The images that provocative art director Oliviero Toscani created for the Italian brand were plastered on walls, in train stations and airports, and across glossy magazines. All were controversial – largely because they contained moments completely unrelated to fashion, such as a newborn baby with the umbilical cord still intact or an artistic reproduction of a man dying of Aids.

Even some of the less visually controversial images – such as a mixed-race lesbian family or a nun and a priest kissing – pushed the boundaries of the era, and led to a backlash from the church and a wide range of specialist groups.

And yet they marked the brand as being on the cutting edge of culture and at the forefront of race and gender politics.

No company, however, can survive on advertising alone, and in the ’80s and ’90s, the retailer became one of the most powerful in the world because of its designs, too.

Its thick, colourful knitwear, striking outerwear and emphasis on oversized silhouettes chimed with the times and earned it stores on Oxford Street in London, the Champs Elysées in Paris and Fifth Avenue in New York.

In the early ’00s, as Asian manufacturing really took off, the real cost of clothing dropped, but Benetton continued to manufacture in Europe, which ensured its designs were at a slightly different price point to all their competitors.

“Benetton managed to be – at the same time – more expensive and less relevant from a fashion viewpoint, which is a recipe for disaster,” says Luca Solca, a senior research analyst at Bernstein specialising in luxury goods.

Then, in 2007, Uniqlo expanded into Europe and the US, stealing almost all its customer base. The Japanese store quickly became the go-to retailer for urban consumers of all ages looking to buy staples such as jumpers, khaki trousers and fashionable outerwear.

Zara, meanwhile, provided colour and fun in everything from miniskirts to jumpers, but with a high-fashion angle and at two-thirds of the price of Benetton. Much of this was thanks to parent company Inditex’s hawk-eyed buyers monitoring the pieces most likely to sell.

“Zara and H&M did two very important things,” says Solca. “H&M systematically sourced in Asia, managing to be cheaper throughout; Zara didn’t even try to impose its take on fashion, but rather relied on fast proximity sourcing to bring consumers the style of the moment.”

Solca also notes that the companies were organised very differently. “All of the ‘company wiring’ and organisation was structured differently,” he says. “Benetton had an army of designers travelling to four corners of the world, and would integrate market perspectives and tastes through no fewer than 100 heads of design in each country.

‘Let me touch you’: kid’s fashion label apologises for offensive T-shirts

“Compare and contrast that with Inditex having a handful of designers and countless customer service personnel on the phone non-stop to get a sense of what the stores would sell, if they only had the right styles.”

Unlike Uniqlo, Benetton, which is still operating and counts more than 3,500 stores worldwide, also never properly adapted to e-commerce. Foot traffic sharply declined from 2012 onwards in its stores in Europe and America, but online sales never picked up enough to solve the problem.

“Ultimately, Benetton was overcome by the Darwinian evolution of fashion retail,” says Solca of a brand that was ahead of the curve in the ’80s and ’90s when it came to so many social issues, but which failed to work out exactly what it was in this very different century.