The very first Lada was released in 1970 in Tolyatti, an industrial city in the USSR. Soviet engineers worked together with Italian carmaker Fiat to create the famous Lada ‘2101’. The car was a major hit for the Soviet, and even the international market, and many other models followed.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the international car market opened to Russians, who were now able to choose from a great variety of foreign brands. However, for many Russians, the old rusty cars made in the Soviet Union and also newer models of the same brand, caused mixed feelings: some thought they were a synonym for the junk from the USSR, while others believed these were the best cars in the world. So, what’s behind Russians’ ongoing obsession with the famous Soviet brand?

The Soviet car brand (now considered ‘Russian’) is a perpetual subject of memes on the internet and Russians often contemptuously call them “rust-buckets”. Yet, Lada sells more new cars in Russia than any foreign brand present in the country.

A popular stereotype has it that Ladas are especially favored by the residents of the Caucasian republics, like Chechnya, Dagestan, and the rest of the Southern and North Caucasus Federal districts.

To be fair, there is much truth to it. Anyone who has been to Russia’s south and the Caucasus will know that domestically made Ladas are the most frequent sight in that part of Russia. In particular, a black pimped Lada Priora has become an unspoken symbol of the region.

A pimped Lada Priora has become an unspoken symbol of Russia’s south and the Caucasus.

Legion mediaResident of Dagestan Amirkhan Kurbanov gives an exhaustive explanation:

“In Dagestan, people have a specific approach to every purchase: if you spend a certain amount of money, you must buy the best product for the price. A new Lada Priora costs akin to a Hyundai Accent or any other dray, if not cheaper. Driving a Hyundai tells everyone you drive a foreign-made car, but a sh*tty one and this is not cool. Driving a Priora, on the other hand, tells everyone that you are not yet ready to pay big money for a car, but that you, nonetheless, got the best for the money you had and now you drive a wonderful car.”

Other models suit drivers in other parts of the country. The new Lada Vesta is a common car in Russia’s capital, Moscow; meanwhile youths especially love to drift in old Soviet models; and the Lada Niva 4x4 is popular among hunters and fishermen residing in more remote regions of the country.

So, it would be an understatement to say that Russians love Lada; it turns out, many Russians also admire it. Even President Putin owns one.

Price is one of the key factors many Russians opt for the homemade brand. A new Lada Granta is as cheap as $5,200 — a fraction of the price any foreign dealer charges for their cars. Used cars sell even cheaper. In fact, it’s possible to buy an old Lada for just a few hundred U.S. dollars — this appeals to beginner drivers, who usually hardly pass the age limit to legally drive.

It’s possible to buy an old Lada for just a few hundred U.S. dollars.

Sergei Vedyashkin/Moskva Agency“I had a Playstation, which I sold for 30,000 rubles (ca. $400). My dad suggested spending the cash on a set of wheels to go drifting in winter,” says Sergey, who bought his first Lada with his father at the age of 13.

Besides, many young Russians appreciate the retro style of these cars that looks quite stunning if properly customized.

Another certain advantage Ladas have over foreign-made cars in Russia is that they are easy to repair. Many Russian owners of more expensive foreign-made cars face long waiting periods for spare parts to arrive from abroad.

Many young Russians appreciate the retro style of these cars that looks quite stunning if properly customized.

Pavel KuzmichevIt’s quite the opposite for a Lada. Spare parts are abundant in every single specialized store in the country. There’s no need to wait even a day and most parts are extremely cheap. What’s even more important is that these cars don’t require much technical knowledge to fix and most of the owners have learned how to do so with their own hands.

“With time passing, other models started to become outdated, their quality deteriorated and they became notorious. But in return, you could buy parts cheaply and repair everything by yourself. Were the spare parts notoriously bad, too? Yes, but you could buy a spare part for a spare part,” says Protas Bardakhanov.

Julia from Moscow used to own a white Lada ‘2105’ when she was a student. She said the car gave her an invaluable driving experience. “It was very cheap to repair. I earned nothing at the time, but I had no problem maintaining the car. This car taught me to deal with a manual transmission: an Audi would have quickly died under such pressure, but these cars forgive novice mistakes.”

Lada also sold cars abroad during the Soviet Union and continues to do so today. Many people living in Europe, Africa and Latin America also have fond memories of these cars, because their parents used to own them.

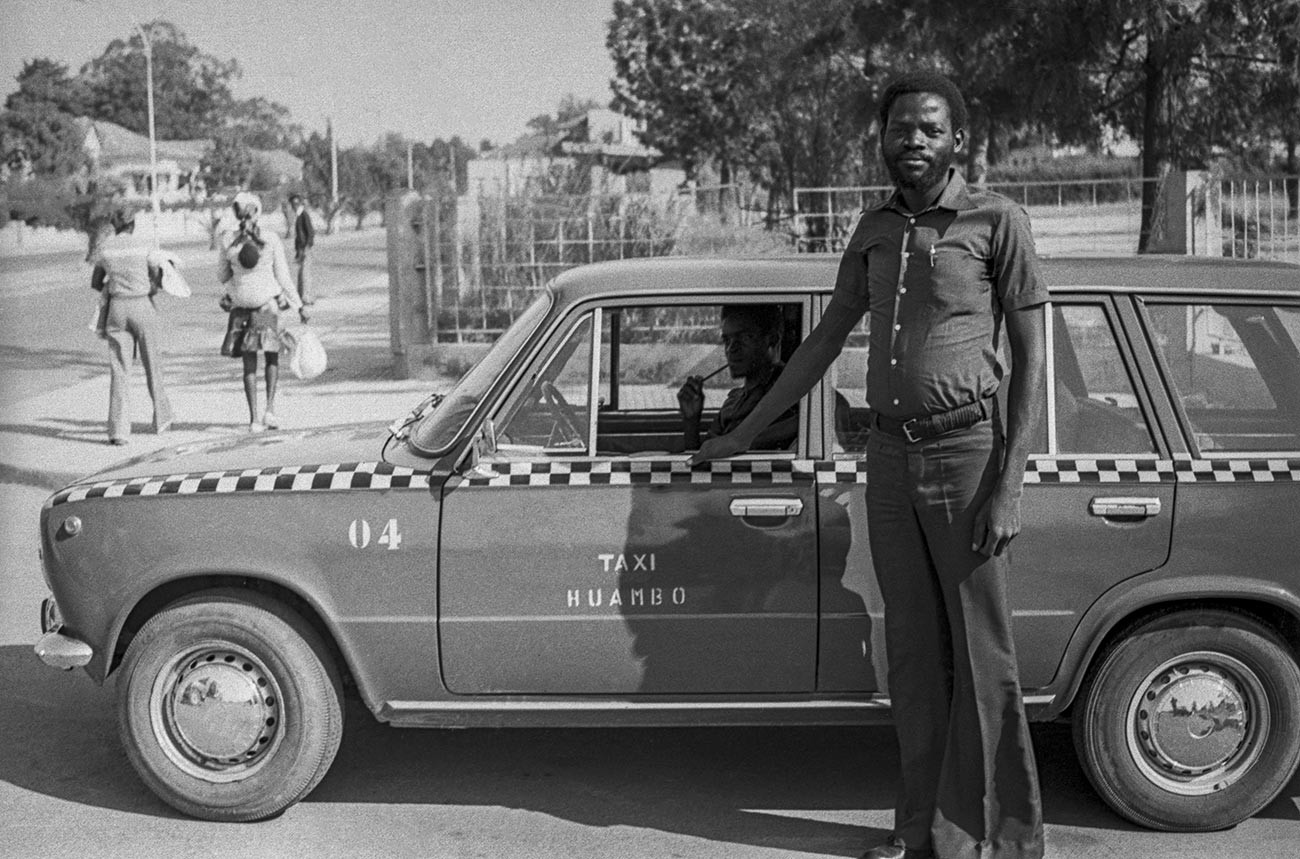

A Lada taxi in Angola.

S. Frolov/TASS“My father used to have Lada Niva. It was a car I liked as a young boy growing up. It was durable and thrived on terrible roads,” says Mohamed Lamin Sesay from Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Musa Tamba from Gambia used to call Lada “the car of Africa”.

Kirill Safonov/TASSMusa Tamba from Gambia said he used to call Lada “the car of Africa”. “The Lada models [in Gambia] were the ‘2104’, ‘2105 COMBI’ and ‘NIVA 4×4’. We called them the ‘car of all terrains’, because of their excellent performance. The engine is fantastic and the body is almost armor plated,” says Musa.

An unusual custom limo model of the Lada 2101 is a popular taxi vehicle in Cuba and the Lada Niva is well known in France.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox