Think of history’s greatest tanks, and the M4 Sherman would seem to be an odd choice.

Its gun was too weak. Its armor was too thin. Its squat shape didn’t have that menacing look of the German panzers.

But gun size and armor thickness aren’t the only attributes that make a great tank. To appreciate that is to understand why the Sherman was key to Allied victory—and why it earned a place in history as one of the most badass tanks.

Hard Times for American Tanks

Had anyone in 1930 been asked whether the U.S. would build 50,000 Shermans during the Second World War, they would have laughed. By the end of the First World War, America had amassed 1,000 newly-developed “landships,” mostly manufactured by France and Britain. A decade later, isolationism and stingy defense budgets had reduced that force to just a few armored vehicles.

Under the National Defense Act of 1920, the Tank Corps was disbanded, and armor fell under the infantry branch, which wanted vehicles that moved at the speed of foot soldiers. The horse cavalry was forbidden to have tanks, so it built “combat cars” (actually light tanks) for scouting.

But by 1939, warfare was changing in tactics and technology. Germany had unleashed blitzkrieg (“lightning war”), which used fast-moving, hard-hitting panzer divisions to annihilate plodding enemy armies stuck in the trench-war mindset of World War I. At the same time, a new generation of tanks had replaced the slow, clumsy rhomboids and toy-like vehicles of World War I. The Second World War became a marathon arms race, especially in armor and aviation. For 150 years, British redcoats essentially used the same Brown Bess musket. In less than a decade, Germany went from the 5-ton Panzer I tank of 1934—armed with just two 7.92-millimeter machine guns—to the 60-ton Tiger I of 1942, armed with an 88-millimeter high-velocity cannon.

Building Tanks From Scratch

Though the Axis powers had been feverishly rearming since the early 1930s, America was barely in the race. Between 1930 and 1939, the U.S. produced only about 500 tanks, compared to 6,000 new German tanks by 1940. In 1939, the U.S. tank arsenal mostly comprised the 12-ton M2A4 light tank, half the weight of the new German Panzer IV and the Soviet T-34 medium tanks.

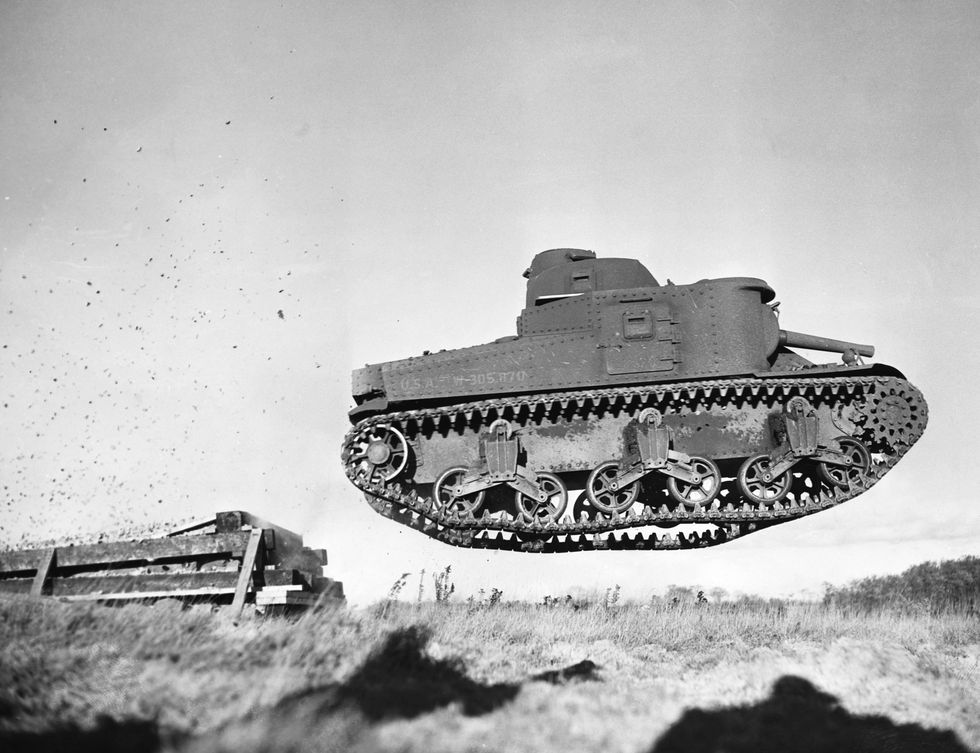

Shocked by how easily the German blitzkrieg conquered most of Western Europe, the U.S. Army hastily designed the bizarre M3 medium tank (called the “Lee” by the Americans, and the “Grant” by the British). The Grant was fully 10 feet tall and armed with a fixed 75-millimeter cannon in the front hull, which required pivoting the entire tank to aim the gun. British crews in North Africa preferred Lend-Lease Grants to notoriously poor British tanks such as the Crusader. Soviet crews nicknamed the Grant “coffin for seven brothers.”

Regardless, the U.S. needed another tank. The result was the M4 Sherman.

A Flawed Concept

Tank design is a delicate balance between firepower, protection, and mobility; the precise mix depends on how an army intends to use the vehicle.

The Americans were diligent enough to study how the German blitzkrieg conquered France in six weeks, but they drew the wrong conclusions. They believed the key to success was to have infantry breach enemy lines, which the tank divisions would then exploit to drive deep into the enemy rear, just as the German panzers had done.

The problem was that senior U.S. Army officers—notably Lt. Gen. Leslie McNair, commander of the Army Ground Forces—believed that American tanks shouldn’t fight other tanks. Instead, that would be the job of anti-tank guns towed by trucks or tank destroyers (such as the M10 and M18 Gun Motor Carriages) that were essentially fast but lightly armored tanks that would pick off the panzers using hit-and-run tactics. The regular tanks would avoid enemy armor and focus on exploiting breakthroughs.

The concept proved disastrous. Towed anti-tank guns were not mobile enough, while the tank destroyers were too thinly armored to take on German tanks.

Yet that philosophy had already shaped the Sherman. If the M4 wasn’t meant to battle enemy tanks, then it didn’t need to have the biggest gun or thickest armor. It merely needed to have adequate firepower, protection, and speed, as long as it was mechanically reliable enough to advance long distances during a breakthrough without requiring extensive logistics and maintenance.

That called for a medium tank. World War II-era armies used a mix of armor classes. Heavy tanks like the 70-ton King Tiger, with a top cross-country speed of 12 miles per hour, could break through enemy defenses—but they were expensive and too slow to exploit a breakthrough. Light tanks, such as the 17-ton U.S M5 Stuart, were cheaper, but were vulnerable on battlefields that became ever more lethal to armored vehicles.

By 1945, armies were moving toward medium tanks, such as the Sherman, the T-34, and Germany’s Panther. These were jack-of-all-trade vehicles that packed enough firepower and protection to survive on the battlefield, while retaining enough mobility to maneuver. After World War II, medium tanks would evolve into modern main battle tanks, such as the M1 Abrams, Leopard 2 and T-72.

An Off-the-Shelf Tank

The Sherman is a prime example of the biggest reason the Allies defeated the Axis: they made better use of their resources. From having virtually no tanks and a peacetime economy, America had to build an armored armada that would eventually grow to 16 armored divisions—plus 70 independent tank battalions—by 1945. In addition, the U.S. had to provide Lend-Lease vehicles for Britain, the Soviet Union, and other nations.

But where would this steel cornucopia come from? The U.S. didn’t have extensive experience in designing and building armored vehicles. What it did have was the world’s greatest automobile manufacturing industry. So the Sherman became an off-the-shelf tank, a standardized weapon built for mass production, using components that American factories could easily churn out.

The Sherman’s chassis came from the Grant. The powerplant was based on aircraft engines from Wright, and automobile engines from General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler. Components flowed from companies that had once produced trucks and railroad engines.

The M4’s 75-millimeter (and later 76-millimeter) guns had respectable anti-tank capability for the 1940s. Perhaps more important was that they could fire reasonably powerful high-explosive shells, a vital consideration given that 80 percent of targets the Sherman engaged were soft targets such as infantry, anti-tank guns, and bunkers. “Tank versus tank fighting was only a small aspect of World War II tank combat,” author Steven Zaloga, who has written numerous books on the Sherman and other tanks, tells Popular Mechanics. “Judging the Sherman simply by this criteria distorts any measure of its overall combat effectiveness.”

The basic Sherman weighed about 33 tons and stood about 9 feet tall. In addition to a main gun, it was armed with one .50-caliber and two .30-caliber machine guns. Armor protection was about 2 inches thick in the front and 1.5 inches on the sides and rear. Despite the reputation of German weapons as having superior technology, the Sherman did have advanced features such as a gyrostabilizer to keep the gun locked on target while the Sherman was moving and a power-assisted turret for faster traverse.

While German tank production and logistics were complicated by manufacturing small quantities of numerous models, the Sherman became the building block of Allied armor in Europe as well as the Pacific. Its versatility enabled more than 70 variants, including medium tanks, assault tanks, amphibious tanks, self-propelled anti-tank guns and artillery, flail tanks to clear mines, recovery vehicles, turret-mounted multiple rocket launchers, flame throwers, and searchlight vehicles.

The Test of Combat

The Sherman was a good tank for its class. “The M4A3, with a 76-millimeter gun, remained comparable or superior to other medium tanks of the period such as the German PzKpfw IV J or Soviet T-34-85,” Zaloga says. “It was not comparable to much heavier tanks such as the Tiger or Panther that had better armor and firepower, but were 10 tons or more heavier.”

But what was an excellent design in 1942 began to lag as the war raged on. The U.S. failed to notice the warning signs, such as the appearance of the Tiger I on the Eastern Front and in North Africa in 1942−1943. The Germans were increasing the firepower and armor of their heavy and medium tanks, but the U.S. Army felt no urgency to do likewise with the Sherman.

Allied tank crews in the Northwest European campaign of 1944−1945 paid the price when massive numbers of Allied and German tanks confronted each other. The Germans employed their full array of sophisticated and deadly armored fighting vehicles. Particularly feared were the “big cats”: heavy Tigers with deadly 88-millimeter guns and thick armor (the Tiger II had seven inches on the front hull), as well as the 45-ton Panther with a long-barreled, high-velocity 75-millimeter gun that outranged the Sherman’s.

To say Allied tank crews were dismayed would be an understatement. A Tiger or Panther could destroy a Sherman from over a mile away, while a Sherman’s shells might bounce off the enemy’s frontal armor unless at point-blank range. The alternative was to use superior numbers to swarm the enemy and gain a side or rear shot. Even if successful, this could only be achieved at fearful cost.

“It’s like hitting them with tennis balls,” complains a U.S. tank commander (played by Telly Savalas) as his Sherman fires on Tigers in the 1965 film Battle of the Bulge. Soon, Allied soldiers reported that every German tank they encountered was a Tiger. Despite “Tiger fright,” Allied tankers did their job—albeit a little more cautiously.

Perhaps the U.S. Army can be forgiven for making erroneous assumptions when designing the Sherman; it wouldn’t be the first or last time in history that military leaders made a wrong prediction about the future battlefield. What was unforgivable was the failure to anticipate that the Sherman would need to be upgraded over time. The Army’s Ordnance Department, and senior leaders such as Patton, either were content with the Sherman’s 75-millimeter gun or felt switching to a larger cannon would create organizational and logistical problems. Only in 1944 came a belated attempt to add a 76-millimeter gun that had a muzzle velocity of just 2,600 feet per second. The Panther’s 75-millimeter gun had a velocity of almost of 3,100 feet.

There were alternatives. The British fitted their 17-pounder anti-tank gun—which could knock out Tigers and Panthers with a frontal shot—to create the Sherman Firefly (though the 17-pounder lacked a high-explosive shell to engage infantry). “There was no technical reason that the U.S. Army should have been the only major army in 1943−44 to fail to develop a new high-velocity tank gun capable of dealing with the panzer threat,” Zaloga wrote in his book Armored Thunderbolt: The U.S. Army Sherman in World War II. “The 76-millimeter gun was a mediocre, half-hearted attempt that was inferior to its contemporaries such as the German 75-millimeter KwK 43 on the Panther, the 17-pounder on the British Sherman Firefly, or the Soviet 85-millimeter gun on the T-34-85.”

Sympathy for the Sherman

Through books with titles such as Death Traps, the Sherman acquired an image as a flawed tank. Some criticisms were justified. For example, early Shermans tended to catch on fire because of poorly designed ammunition stowage (which was eventually corrected by adding armored “wet stowage” ammo racks).

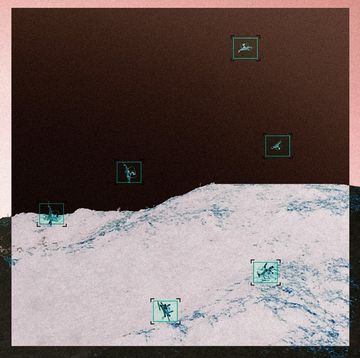

But ultimately, this argument misses the point. Building small numbers of powerful—but also over-engineered and high-maintenance—weapons was the mistake that Germany made. Despite the myth of the Second World War as blitzkrieg, the reality was that the conflict was really a war of attrition in which more than 67,000 tanks were destroyed. To absorb those losses and keep fighting, the U.S. built 50,000 Shermans and the Soviets 57,000 T-34s. Germany built 2,000 Tigers and 6,000 Panthers.

To advance across Europe and into Germany, the Allies also needed a reliable tank. The Sherman’s finest hour came during the breakout from the Normandy bridgehead in July 1944. Within a month, M4-equipped Allied divisions had advanced 400 miles across France and the Low Countries to reach the German border. German panzer divisions attempting this feat in 1944 would have left a trail of broken-down Tigers and Panthers before they could even advance 150 miles to Paris. “Neither German nor Soviet tanks were as reliable as the Sherman during prolonged campaigns,” Zaloga says.

Ironically, some of the biggest fans of the Sherman were the Russians. For Soviet crews accustomed to crudely manufactured tanks like the T-34, the 4,100 Lend-Lease Shermans seemed luxurious. The M4’s rubber tracks were quieter than, and had double the lifespan of, the T-34’s steel tracks. The Sherman was more ergonomic than the cramped and uncomfortable T-34, and even had padded seats. Soviet crews soon learned to keep an eye on any damaged Sherman, recalled Dimitri Loza, author of Commanding the Red Army’s Sherman Tanks.

“If it was left unguarded literally for just several minutes,” Loza told a Russian history site, “the infantry would strip out all this upholstery. It made excellent boots!”

The T-34 emerged as one of the great tanks of World War II. Yet U.S engineers who tested the T-34 found that “Russian tanks are significantly inferior to American tanks in their simplicity of driving, maneuverability, the strength of firing (reference to muzzle velocity), speed, the reliability of mechanical construction and the ease of keeping them running,” according to a Soviet intelligence report.

The Super Sherman

The Sherman’s combat history didn’t end in 1945. The U.S. used them in the Korean War, and they saw combat in the armies of both India and Pakistan when those two nations fought in 1965.

But the most famous post-World War II user of the Sherman is Israel, which upgraded about 500 surplus Shermans, acquired in the 1950s, to create a new vehicle called the “ISherman” or “Super Sherman.” The M50 featured a more powerful French 75-millimeter gun from the AMX-13 light tank. In the 1956 and 1967 wars, it performed well against postwar tanks, including Soviet-made T-54s and American-made M-48s. Especially striking was the M51, armed with a French 105-millimeter cannon, which successfully battled the latest Soviet-made T-55 and T-62 tanks in the 1973 October War.

By the primary metrics of classic tank design, the Sherman excelled neither in firepower, protection or mobility. But as the German panzers proved, the tank with the most impressive technical stats is not necessarily the most successful one. The best tank is the one that accomplishes its mission. And that the Sherman did.

Michael Peck writes about defense and international security issues, as well as military history and wargaming. His work has appeared in Defense News, Foreign Policy Magazine, Politico, National Defense Magazine, The National Interest, Aerospace America and other publications. He holds an MA in Political Science from Rutgers University.