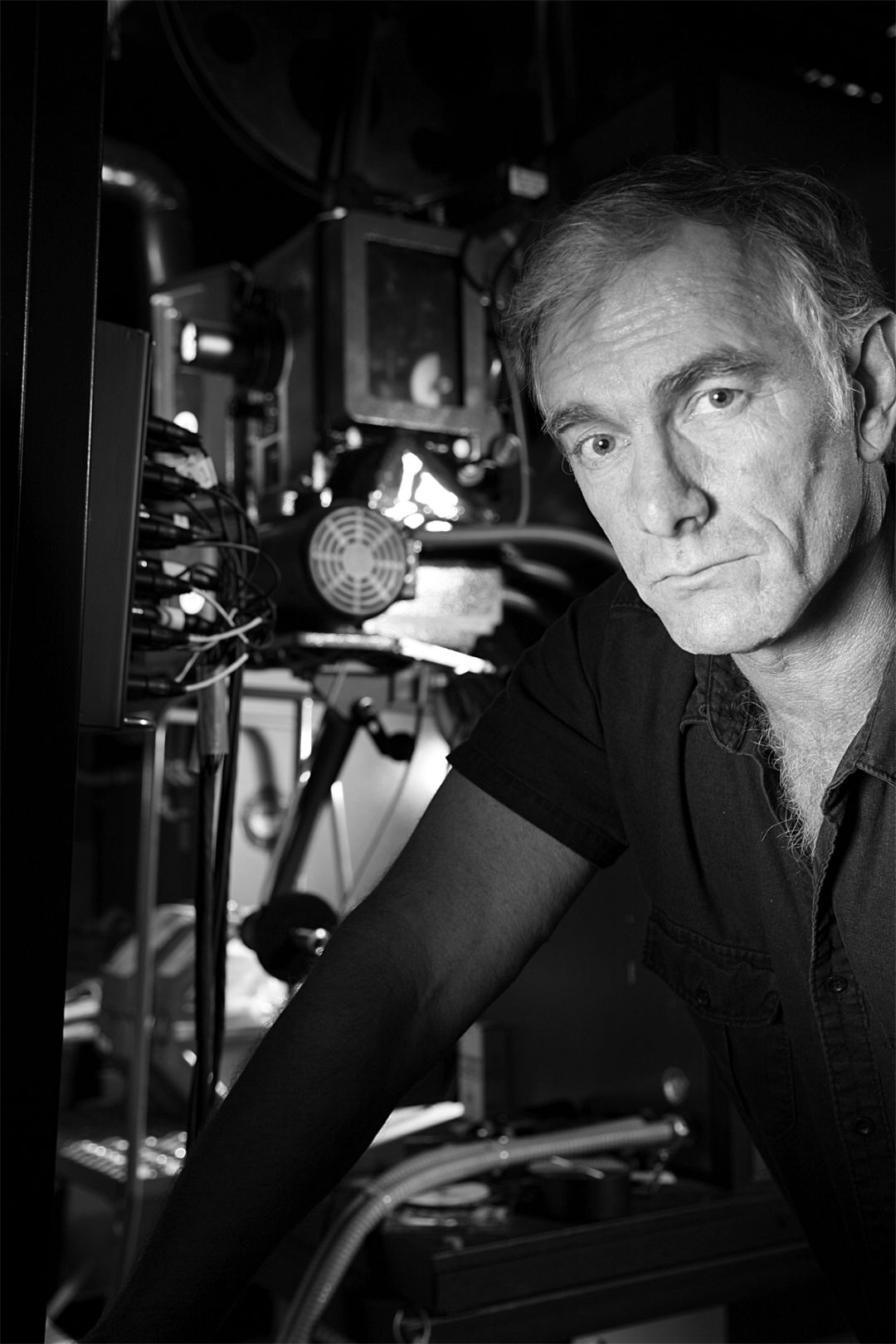

Q&A: Film Director and Novelist John Sayles

John Sayles

Image: Courtesy Ric Kallaher

John Sayles has carved out a singular career both in and out of Hollywood, working on popular screenplays over the years—including fun horror flicks for Joe Dante (Piranha, The Howling) and the Portland-filmed Breaking In, with Burt Reynolds—while establishing himself as a respected independent director and fiction writer. A graduate of Williams College and a MacArthur “genius grant” winner, the Schenectady, New York native falls comfortably into worlds that aren’t necessarily his own, from the Irish seaside (The Secret of Roan Inish) to the Alabama blue circuit of the 1950s (Honeydripper) to a war-torn Mexican jungle (Hombres Armados/Men With Guns)

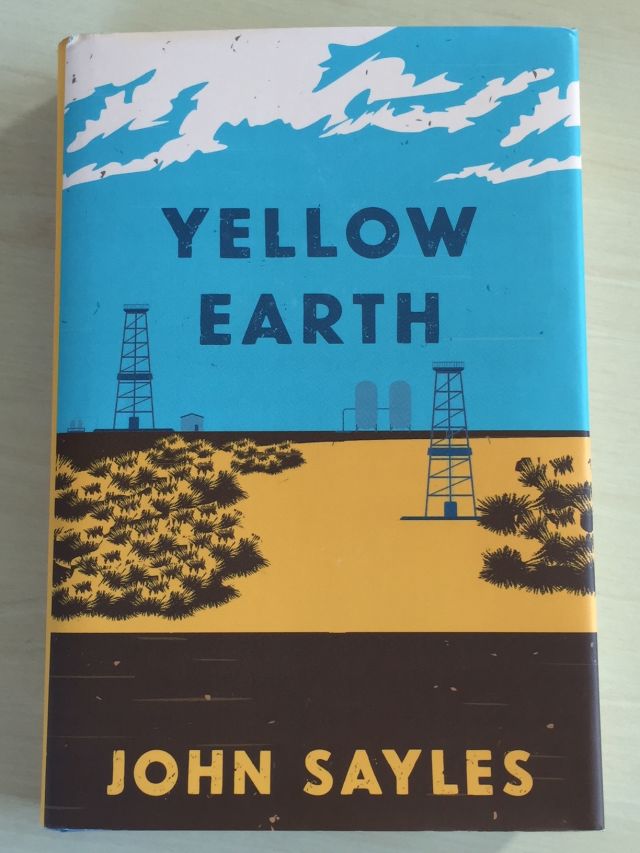

His latest novel, Yellow Earth (published in January by Haymarket Books), tracks what happens to a small community in North Dakota during the Baaken oil boom, and draws parallels to other resource-extraction bonanzas that happened to the same patch of dirt over the centuries, from the frenzy over beaver pelts to buffalo hoarding to overfarming. (For readers not familiar with the Baaken timeline, a character’s curiosity about those newfangled iPods will clue you in on the era.)

We checked in with Sayles by phone as he worked his way up the West Coast toward Portland for a reading at Powell’s City of Books on Thursday, February 27.

Let’s start with some of the character names in Yellow Earth: Harleigh Killdeer, Randy Hardacre, Bunny, Buzzy, Leia, Mike and Ike….

Dickens was probably the best with names, a little broader than mine. I’ve written a novel since Yellow Earth that’s set in 1750, so those names are even more Dickensian. You try to get a feel for a person from a name. You want the names to be different from each other, you don’t want a Phil and a Phillip, a Bob and a Robert, that kind of stuff you run into in real life. You want the reader to be able to pick out that name right away, especially when you have a cast of dozens like Yellow Earth does.

Is it strange writing a “period piece” set so recently, based on real events?

My book about our long dance with the Cubans (Los Gusanos) is set in 1981 during the Freedom Flotilla down in Miami, and I was writing it 10 to 15 years later. Union Dues I wrote around 1980, and that was set around ’68, ’70, ’71. I think it takes a while to synthesize experience and for information to kind of come in about it. I was monitoring the situation in the Baaken shale oil fields while it was happening. I had thought about writing something about that kind of invasion for a long time. Probably about 25, 30 years ago there was a similar situation in Wyoming around Green River, and because they didn’t have their technology together then it was very short; they realized they were losing money pretty quickly, but it left the same kind of mess. My last book, A Moment in the Sun, starts in the Yukon during the gold rush. I’ve always kind of been fascinated by what happens to a community. In the case of Yellow Earth it was a community of 15,000 that in six months had 45,000 people, and most of those 30,000 that showed up were youngish men without families. I was watching news reports and reading oil company materials during it. I was involved in movies and stuff like that, so it took me a while to get around to writing it.

Parts of Yellow Earth remind me of Deadwood, the HBO series about the gold rush town.

I’ve always felt like Deadwood and its various seasons were a good primer on the absolute free market and then the early stirrings of capitalism. The later episodes were kind of about when the corporate world gets organized and decides to come in and take over a place.

Are there things you can do in books you can’t do in movies, or vice-versa? Could you imagine making a movie of Yellow Earth?

Just practically, I just don’t think I could do the drilling part. I don’t know of any company that would let me come and watch them frack and drill and then let me make them look bad. My whole thing about the fracking, it is what it is—it’s just that when the companies subcontract and subcontract and subcontract so they’re not responsible for the cleanup, they’re basically getting away with a kind of theft, and if they actually had to pay for all the mess that they leave, they might not do it in the first place because it wouldn’t be economically feasible.

It’s hard to get [a lot] into a two-hour movie. Some of the things I’ve written would make a five-year miniseries—or more in the case of A Moment in the Sun. So far nobody’s asking to make any of them into movies or TV shows [Sayles laughs], and I haven’t had much luck raising money to make the movies that I have written in the past 15 years or so. They’re different things. There’s things that you can do in a move that you can’t do in a book. In the new book that I’ve written, there’s a lot of people speaking different languages, and in a movie you can have them speak those languages and have subtitles. In a book ... you have to find very different ways to accommodate that. In each thing you have to have a different approach, and that affects the story that you tell.

You’re a white American guy who can make a movie about Ireland that Irish people like, a movie set among Spanish speakers that you’re not pilloried for (compared to the reaction to something like American Dirt). How is it that you don’t piss people off?

I think some of it is just that you have to be able to pull it off, and that means listening, doing a lot of listening, and a certain amount of research. In the case of movies, you also have the actors’ experience and their backgrounds, and you try to pick people that can understand who they’re playing and have some of that background themselves. I’m actually a big advocate of open casting in theater … but in movies if someone is Native American I find a Native American actor, and they’re going to bring something to it that somebody else would have to do an awful lot of research to feel like they could pull it off. The other part is I think you always start, or I always start, with the basic human being, and figure that stuff out first, and then you say, OK, how does their age or their race or their class or their sex affect that? When I do a period piece, whether it’s a movie or a book, I’m not a big fan of saying OK, let’s have fun and go do Emily Dickinson but have people talk in contemporary terms so it’s more fun. I’m more a fan of saying, OK, this is before the women’s movement, this is before Freud, sometimes this is before capitalism, or this is before people knew the world was round. Let’s try to get into those heads and what they could possibly think. Are they people who believe in the official story, or are they people who think outside the box a little bit, and what does that cost them if they think outside the box?

Books or films, have you ever set anything in the Pacific Northwest?

In A Moment in the Sun, Seattle was the jump-off point for the Yukon, so early in the book there’s some stuff in Seattle. I think that’s the only thing I’ve set there. I tried to shoot there once, up in Port Townsend, because Fort Warden there would be a great setting for this movie that I wrote about the Carlisle Indian School back in Pennsylvania. But I don’t think I have set anything specifically there.

A lot of your film work has such a rich sense of place: Louisiana in Passion Fish, the Texas border town in Lone Star, Florida in Sunshine State. Are there regional writers you like who bring that to the page?

Most of Louise Erdrich’s stuff is set around the Great Lakes where then Anishinaabe people live. I’ve been reading stuff by James Welch, who’s a Native American writer also. His stuff is mostly set in Montana. There’s a bunch of good Florida writers, and there’s kind of a Miami noir. I read a lot of Mari Sandoz, from a Swiss immigrant family that lived in Nebraska, and she’s a wonderful writer. There’s good Los Angeles writers, not all of them born there—like Raymond Chandler, who had a really interesting take on Los Angeles of a certain period. It’s something I do enjoy, when somebody really knows a place. There’s a terrific—she writes horror thrillers and stuff like that— Scotswoman named Denise Mina whose stuff is often set in Glasgow. Irvine Welsh, who wrote Trainspotting, writes really well about Edinburgh. People take you to the place. And if they really know it, you get to spend some time there without necessarily ever going there.

John Sayles at Powell’s City of Books, 1005 W Burnside St, 7:30 p.m. Thursday, Feb 27